The Fossil Record of Angiosperm Families in Relation to Baraminology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

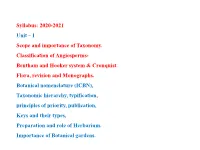

I Scope and Importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker System & Cronquist

Syllabus: 2020-2021 Unit – I Scope and importance of Taxonomy. Classification of Angiosperms- Bentham and Hooker system & Cronquist. Flora, revision and Monographs. Botanical nomenclature (ICBN), Taxonomic hierarchy, typification, principles of priority, publication, Keys and their types, Preparation and role of Herbarium. Importance of Botanical gardens. PLANT KINGDOM Amongst plants nearly 15,000 species belong to Mosses and Liverworts, 12,700 Ferns and their allies, 1,079 Gymnosperms and 295,383 Angiosperms (belonging to about 485 families and 13,372 genera), considered to be the most recent and vigorous group of plants that have occurred on earth. Angiosperms occupy the majority of the terrestrial space on earth, and are the major components of the world‘s vegetation. Brazil (First) and Colombia (second), both located in the tropics considered to be countries with the most diverse angiosperms floras China (Third) even though the main part of her land is not located in the tropics, the number of angiosperms still occupies the third place in the world. In INDIA there are about 18042 species of flowering plants approximately 320 families, 40 genera and 30,000 species. IUCN Red list Categories: EX –Extinct; EW- Extinct in the Wild-Threatened; CR -Critically Endangered; VU- Vulnerable Angiosperm (Flowering Plants) SPECIES RICHNESS AROUND THE WORLD PLANT CLASSIFICATION Historia Plantarum - the earliest surviving treatise on plants in which Theophrastus listed the names of over 500 plant species. Artificial system of Classification Theophrastus attempted common groupings of folklore combined with growth form such as ( Tree Shrub; Undershrub); or Herb. Or (Annual and Biennials plants) or (Cyme and Raceme inflorescences) or (Archichlamydeae and Meta chlamydeae) or (Upper or Lower ovarian ). -

Thymelaeaceae)

Origin and diversification of the Australasian genera Pimelea and Thecanthes (Thymelaeaceae) by MOLEBOHENG CYNTHIA MOTS! Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in BOTANY in the FACULTY OF SCIENCE at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Dr Michelle van der Bank Co-supervisors: Dr Barbara L. Rye Dr Vincent Savolainen JUNE 2009 AFFIDAVIT: MASTER'S AND DOCTORAL STUDENTS TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This serves to confirm that I Moleboheng_Cynthia Motsi Full Name(s) and Surname ID Number 7808020422084 Student number 920108362 enrolled for the Qualification PhD Faculty _Science Herewith declare that my academic work is in line with the Plagiarism Policy of the University of Johannesburg which I am familiar. I further declare that the work presented in the thesis (minor dissertation/dissertation/thesis) is authentic and original unless clearly indicated otherwise and in such instances full reference to the source is acknowledged and I do not pretend to receive any credit for such acknowledged quotations, and that there is no copyright infringement in my work. I declare that no unethical research practices were used or material gained through dishonesty. I understand that plagiarism is a serious offence and that should I contravene the Plagiarism Policy notwithstanding signing this affidavit, I may be found guilty of a serious criminal offence (perjury) that would amongst other consequences compel the UJ to inform all other tertiary institutions of the offence and to issue a corresponding certificate of reprehensible academic conduct to whomever request such a certificate from the institution. Signed at _Johannesburg on this 31 of _July 2009 Signature Print name Moleboheng_Cynthia Motsi STAMP COMMISSIONER OF OATHS Affidavit certified by a Commissioner of Oaths This affidavit cordons with the requirements of the JUSTICES OF THE PEACE AND COMMISSIONERS OF OATHS ACT 16 OF 1963 and the applicable Regulations published in the GG GNR 1258 of 21 July 1972; GN 903 of 10 July 1998; GN 109 of 2 February 2001 as amended. -

Infructescences of Kasicarpa Gen. Nov. (Hamamelidales) from the Late Cretaceous (Turonian) of the Chulym-Yenisey Depression, Western Siberia, Russia*

Acta Palaeobotanica 45(2): 121–137, 2005 Infructescences of Kasicarpa gen. nov. (Hamamelidales) from the late Cretaceous (Turonian) of the Chulym-Yenisey depression, western Siberia, Russia* NATALIA P. MASLOVA 1, LENA B. GOLOVNEVA 2 and MARIA V. TEKLEVA 1 1 Palaeontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Profsoyuznaya 123, Moscow, 117647 Russia; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 2 V. L. Komarov Botanical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Professora Popova st., 2, St.-Petersburg, 197376 Russia; e-mail: [email protected] Received 09 Mai 2005; accepted for publication 10 November 2005 ABSTRACT. Kasicarpa gen. nov. is erected for pistillate heads from the Turonian deposits of the Chulym-Yeni- sey depression, western Siberia, Russia. The heads consist of about 30–40 floral units at different development stages. Flowers of the new described genus have a well-developed perianth and monocarpous gynoecium. The fruit has a single orthotropous seed. The well-preserved seed has a single integument (one single cell layer) and thick endosperm. The new genus combines characters of the families Platanaceae and Hamamelidaceae. The leaves of a platanoid morphology associating with these heads have been previously described as Populites pseudoplatanoides I. Lebedev, 1955. KEY WORDS: fossil, reproductive structures, microstructure, Hamamelidales, late Cretaceous, Russia INTRODUCTION The evolutionary history of the Platanaceae (Maslova & Krassilov 2002), staminate heads and Hamamelidaceae are entirely different. Tricolpopollianthus (Krassilov 1973), Platan- Currently, the Platanaceae is a monotypic fam- anthus (Manchester 1986), Aquia (Crane et ily: the genus Platanus is the single remnant al. 1993), Hamatia (Pedersen et al. 1994), of a once extensive and diverse plant group. -

Dilleniidae À Carpelles Fermés Malvales Euphorbiales 3

1- DILLENIIDAE PRIMITIVES THEALES DILLENIALES 2- DILLENIIDAE À CARPELLES FERMÉS MALVALES EUPHORBIALES 3- DILLENIIDAE À CARPELLES OUVERTS VIOLALES SALICALES SALICACEAE Populus, Salix TAMARICALES PASSIFLORALES CUCURBITALES CAPPARALES BEGONIALES 4- DILLENIIDAE À PÉTALES SOUDÉS ERICALES EBENALES Salicales - 1 - Ordre des SALICALES Famille des SALICACEAE (une seule famille) 3 ou 4 genres et 300 espèces dans le monde, dans les zones tempérées et subpolaires. Chez nous, 2 genres : Populus (8 espèces) et Salix (30 espèces). Chatons pendants, bractées découpées chez les peupliers qui sont d'avantage dans l'hémisphère nord. Cupules chez les peupliers. Deux genres très anciens (éocène inférieur). Les espèces sont pour la plupart dioïques, les fleurs naissent à l'aisselle d'une bractée. 2 à 30 étamines libres ou soudées. Fleurs femelles : deux carpelles ouverts et soudés, où l'on trouve des ovules anatropes à 1 ou 2 téguments. Fleur apérianthées. Le fruit est une capsule contenant de nombreuses graines poilues (aménophiles = dispersées par le vent). Sur sols alluvionnaires, espèces assez héliophiles. Le bois est de peu de valeur, mais a quand même une importance économique, car il a une croissance très rapide. On l'utilise pour le caissage, la pâte à papier, les allumettes. Les espèces du genre Populus ont les feuilles longuement pétiolées, chatons pendants (adaptation à la pollinisation), chatons à l’aisselle de bractées découpées, cupules à la base des fleurs, anthères rougeâtres, plutôt dans l'hémisphère Nord. Les espèces du genre Salix : Feuilles subsessiles, chatons dressés, fleur à l’aisselle de bractées entières. Nombreux hybrides (jusqu'à une centaine), polymorphisme important des feuilles (il existe des feuilles circulaires) ; régions subarctiques à tempérées chaudes de l’hémisphère Nord. -

Arthur Monrad Johnson Colletion of Botanical Drawings

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7489r5rb No online items Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Processed by Pat L. Walter. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division History and Special Collections Division UCLA 12-077 Center for Health Sciences Box 951798 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1798 Phone: 310/825-6940 Fax: 310/825-0465 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/biomed/his/ ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion 48 1 of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Descriptive Summary Title: Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings, Date (inclusive): 1914-1941 Collection number: 48 Creator: Johnson, Arthur Monrad 1878-1943 Extent: 3 boxes (2.5 linear feet) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Approximately 1000 botanical drawings, most in pen and black ink on paper, of the structural parts of angiosperms and some gymnosperms, by Arthur Monrad Johnson. Many of the illustrations have been published in the author's scientific publications, such as his "Taxonomy of the Flowering Plants" and articles on the genus Saxifraga. Dr. Johnson was both a respected botanist and an accomplished artist beyond his botanical subjects. Physical location: Collection stored off-site (Southern Regional Library Facility): Advance notice required for access. Language of Material: Collection materials in English Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings (Manuscript collection 48). Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division, University of California, Los Angeles. -

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 185 Map 2: Andean-North Patagonian Biosphere Reserve: Context for the Nominated Proprty. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 186 Map 3: Vegetation of the Valdivian Ecoregion 187 Map 4: Vegetation Communities in Los Alerces National Park 188 Map 5: Strict Nature and Wildlife Reserve 189 Map 6: Usage Zoning, Los Alerces National Park 190 Map 7: Human Settlements and Infrastructure 191 Appendix 2: Species Lists Ap9n192 Appendix 2.1 List of Plant Species Recorded at PNLA 193 Appendix 2.2: List of Animal Species: Mammals 212 Appendix 2.3: List of Animal Species: Birds 214 Appendix 2.4: List of Animal Species: Reptiles 219 Appendix 2.5: List of Animal Species: Amphibians 220 Appendix 2.6: List of Animal Species: Fish 221 Appendix 2.7: List of Animal Species and Threat Status 222 Appendix 3: Law No. 19,292 Append228 Appendix 4: PNLA Management Plan Approval and Contents Appendi242 Appendix 5: Participative Process for Writing the Nomination Form Appendi252 Synthesis 252 Management Plan UpdateWorkshop 253 Annex A: Interview Guide 256 Annex B: Meetings and Interviews Held 257 Annex C: Self-Administered Survey 261 Annex D: ExternalWorkshop Participants 262 Annex E: Promotional Leaflet 264 Annex F: Interview Results Summary 267 Annex G: Survey Results Summary 272 Annex H: Esquel Declaration of Interest 274 Annex I: Trevelin Declaration of Interest 276 Annex J: Chubut Tourism Secretariat Declaration of Interest 278 -

Wood Anatomy of Buddlejaceae Sherwin Carlquist Santa Barbara Botanic Garden

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 15 | Issue 1 Article 5 1996 Wood Anatomy of Buddlejaceae Sherwin Carlquist Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Carlquist, Sherwin (1996) "Wood Anatomy of Buddlejaceae," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 15: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol15/iss1/5 Aliso, 15(1), pp. 41-56 © 1997, by The Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA 91711-3157 WOOD ANATOMY OF BUDDLEJACEAE SHERWIN CARLQUIST' Santa Barbara Botanic Garden 1212 Mission Canyon Road Santa Barbara, California 93110-2323 ABSTRACT Quantitative and qualitative data are presented for 23 species of Buddleja and one species each of Emorya, Nuxia, and Peltanthera. Although crystal distribution is likely a systematic feature of some species of Buddleja, other wood features relate closely to ecology. Features correlated with xeromorphy in Buddleja include strongly marked growth rings (terminating with vascular tracheids), narrower mean vessel diameter, shorter vessel elements, greater vessel density, and helical thickenings in vessels. Old World species of Buddleja cannot be differentiated from New World species on the basis of wood features. Emorya wood is like that of xeromorphic species of Buddleja. Lateral wall vessel pits of Nuxia are small (2.5 ILm) compared to those of Buddleja (mostly 5-7 ILm) . Peltanthera wood features can also be found in Buddleja or Nuxia; Dickison's transfer of Sanango from Buddlejaceae to Ges neriaceae is justified. All wood features of Buddlejaceae can be found in families of subclass Asteridae such as Acanthaceae, Asteraceae, Lamiaceae, Myoporaceae, Scrophulariaceae, and Verbenaceae. -

<I>Soyauxia</I> (Peridiscaceae, Formerly Medusandraceae)

Plant Ecology and Evolution 148 (3): 409–419, 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.5091/plecevo.2015.1040 REGULAR PAPER A synopsis of Soyauxia (Peridiscaceae, formerly Medusandraceae) with a new species from Liberia Frans J. Breteler1,*, Freek T. Bakker2 & Carel C.H. Jongkind3 1Grintweg 303, NL-6704 AR Wageningen, The Netherlands (previously Herbarium Vadense, Wageningen) 2Biosystematics Group, Wageningen University, P.O. Box 647, NL-6700 AP, Wageningen, The Netherlands 3Botanic Garden Meise, Nieuwelaan 38, BE-1860 Meise, Belgium *Author for correspondence: [email protected] Background – Botanical exploration of the Sapo National Park in Liberia resulted in the discovery of a new species, which, after DNA investigation, was identified as belonging to Soyauxia of the small family Peridiscaceae. Methods – Normal practices of herbarium taxonomy and DNA sequence analysis have been applied. All the relevant herbarium material has been studied, mainly at BR, K, P, and WAG. The presented phylogenetic relationships of the new Soyauxia species is based on rbcL gene sequence comparison, inferred by a RAxML analysis including 100 replicates fast bootstrapping. The distribution maps have been produced using Map Maker Pro. Relevant collection data are stored in the NHN (Nationaal Herbarium Nederland) database. Key results − The new species Soyauxia kwewonii and an imperfectly known species are treated in the framework of a synopsis with the six other species of the genus. rbcL sequence comparison followed by RAxML analyses yielded a well-supported match of S. kwewonii with the Soyauxia clade. Its conservation status according to the IUCN red list criteria is assessed as Endangered. Its distribution as well as the distribution areas of the genus and of the remaining species are mapped. -

Plant Life MagillS Encyclopedia of Science

MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE MAGILLS ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE PLANT LIFE Volume 4 Sustainable Forestry–Zygomycetes Indexes Editor Bryan D. Ness, Ph.D. Pacific Union College, Department of Biology Project Editor Christina J. Moose Salem Press, Inc. Pasadena, California Hackensack, New Jersey Editor in Chief: Dawn P. Dawson Managing Editor: Christina J. Moose Photograph Editor: Philip Bader Manuscript Editor: Elizabeth Ferry Slocum Production Editor: Joyce I. Buchea Assistant Editor: Andrea E. Miller Page Design and Graphics: James Hutson Research Supervisor: Jeffry Jensen Layout: William Zimmerman Acquisitions Editor: Mark Rehn Illustrator: Kimberly L. Dawson Kurnizki Copyright © 2003, by Salem Press, Inc. All rights in this book are reserved. No part of this work may be used or reproduced in any manner what- soever or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy,recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address the publisher, Salem Press, Inc., P.O. Box 50062, Pasadena, California 91115. Some of the updated and revised essays in this work originally appeared in Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science (1991), Magill’s Survey of Science: Life Science, Supplement (1998), Natural Resources (1998), Encyclopedia of Genetics (1999), Encyclopedia of Environmental Issues (2000), World Geography (2001), and Earth Science (2001). ∞ The paper used in these volumes conforms to the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48-1992 (R1997). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Magill’s encyclopedia of science : plant life / edited by Bryan D. -

Commelina Communis

Commelina communis Commelina communis Asiatic dayflower Introduction The genus Commelina has approximately 100 species worldwide, distributed primarily in tropical and temperate regions. Eight species occur in China[60][167] . Species of Commelina in China Flower of Commelina communis. (Photo pro- Scientific Name Scientific Name vided by LBJWC, Albert, F. W. Frick, Jr.) C. auriculata Bl. C. maculata Edgew. C. bengalensis L. C. paludosa Bl. roadsides [60]. C. communis L. C. suffruticosa Bl. Distribution C. diffusa Burm. f. C. undulata R. Br. C. communis is widely distributed in China, [60] but no records are reported stalk, often hirsute-ciliate marginally, Taxonomy for its distribution in Qinghai, Xinjiang, and acute apically. Cyme inflorescence [6][116][167] Family: Commelinaceae Hainan, and Tibet . has one flower near the top, with dark Genus: Commelina L. blue petals and membranous sepals 5 Economic Importance mm long. Capsules are elliptic, 5–7 Description Commelina communis has caused serious mm, and two-valved. The two seeds Commelina communis is an annual damage in the orchards of northeastern in each valve are brown-yellow, 2–3 [96] herb with numerous branched, creeping China . C. communis is used in Chinese mm long, irregularly pitted, flat-sided, [60] stems, which are minutely pubescent herbal medicine. and truncate at one end[60][167]. distally, 1 m long. Leaves are lanceolate to ovate-lanceolate, 3–9 cm long and Related Species 1.5–2 cm wide. Involucral bracts Habitat C. diffusa occurs in forests, thickets C. communis prefers moist, shady forest grow opposite the leaves. Bracts are and moist areas of southern China and edges. -

GENOME EVOLUTION in MONOCOTS a Dissertation

GENOME EVOLUTION IN MONOCOTS A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Kate L. Hertweck Dr. J. Chris Pires, Dissertation Advisor JULY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled GENOME EVOLUTION IN MONOCOTS Presented by Kate L. Hertweck A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. J. Chris Pires Dr. Lori Eggert Dr. Candace Galen Dr. Rose‐Marie Muzika ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for their assistance during the course of my graduate education. I would not have derived such a keen understanding of the learning process without the tutelage of Dr. Sandi Abell. Members of the Pires lab provided prolific support in improving lab techniques, computational analysis, greenhouse maintenance, and writing support. Team Monocot, including Dr. Mike Kinney, Dr. Roxi Steele, and Erica Wheeler were particularly helpful, but other lab members working on Brassicaceae (Dr. Zhiyong Xiong, Dr. Maqsood Rehman, Pat Edger, Tatiana Arias, Dustin Mayfield) all provided vital support as well. I am also grateful for the support of a high school student, Cady Anderson, and an undergraduate, Tori Docktor, for their assistance in laboratory procedures. Many people, scientist and otherwise, helped with field collections: Dr. Travis Columbus, Hester Bell, Doug and Judy McGoon, Julie Ketner, Katy Klymus, and William Alexander. Many thanks to Barb Sonderman for taking care of my greenhouse collection of many odd plants brought back from the field. -

Glyphosate-Tolerant Asiatic Dayflower (Commelina Communis

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 Glyphosate-tolerant Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis L.): Ecological, biological and physiological factors contributing to its adaptation to Iowa agronomic systems Jose Maria Gomez Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gomez, Jose Maria, "Glyphosate-tolerant Asiatic dayflower (Commelina communis L.): Ecological, biological and physiological factors contributing to its adaptation to Iowa agronomic systems" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12332. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12332 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Glyphosate-tolerant Asiatic dayflower ( Commelina communis L.): Ecological, biological and physiological factors contributing to its adaptation to Iowa agronomic systems by José María Gómez Vargas A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Crop Production and Physiology (Weed Science) Program of Study Committee: Micheal D.K. Owen, Major Professor Lynn G. Clark Robert Hartzler Allen Knapp Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v THESIS ORGANIZATION vi CHAPTER 1. GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction 1 Literature review 2 General description of Commelina species 2 Asiatic dayflower history and general characteristics 2 Glyphosate and glyphosate-tolerant crops 5 Weed shifts in glyphosate-tolerant crops 6 Herbicide resistance and tolerance 7 Weed seed bank and seed burial depth 8 Literature cited 11 CHAPTER 2.