UC Berkeley Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

A Comparative Study of Angami and Chakhesang Women

A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF UNEMPLOYMENT PROBLEM : A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF ANGAMI AND CHAKHESANG WOMEN THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIOLOGY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES NAGALAND UNIVERSITY BY MEDONUO PIENYÜ Ph. D. REGISTRATION NO. 357/ 2008 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. KSHETRI RAJENDRA SINGH DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY NAGALAND UNIVERSITY H.Qs. LUMAMI, NAGALAND, INDIA NOVEMBER 2013 I would like to dedicate this thesis to my Mother Mrs. Mhasivonuo Pienyü who never gave up on me and supported me through the most difficult times of my life. NAGALAND UNIVERSITY (A Central University Estd. By the Act of Parliament No 35 of 1989) Headquaters- Lumami P.O. Mokokchung- 798601 Department of Sociology Ref. No……………. Date………………. CERTIFICATE This is certified that I have supervised and gone through the entire pages of the Ph.D. thesis entitled “A Sociological Study of Unemployment Problem: A Comparative Study of Angami and Chakhesang Women” submitted by Medonuo Pienyü. This is further certified that this research work of Medonuo Pienyü, carried out under my supervision is her original work and has not been submitted for any degree to any other university or institute. Supervisor Place: (Prof. Kshetri Rajendra Singh) Date: Department of Sociology, Nagaland University Hqs: Lumami DECLARATION The Nagaland University November, 2013. I, Miss. Medonuo Pienyü, hereby declare that the contents of this thesis is the record of my work done and the subject matter of this thesis did not form the basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and that thesis has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other university/ institute. -

A RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R

A RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh James A. Miller Independent Scholar This paper presents a reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic, the putative ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages, a Tibeto-Burman subgroup. A reconstructed rhyme inventory for the proto-language is presented. Correspondence sets for each of the members of the inventory are then systematically presented, along with supporting cognate sets drawn from four Tangkhulic languages: Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, and Tusom. This paper also summarizes the major sound changes that relate Proto-Tangkhulic to the daughter languages on which the reconstruction is based. It is concluded that Proto-Tangkhulic was considerably more conservative than any of these languages. It preserved the Proto-Tibeto-Burman length distinction in certain contexts and reflexes of final *-l, even though these are not preserved as such in Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, or Tusom. Proto-Tangkhulic is argued to be a potentially useful source of evidence in the reconstruction of Proto-Tibeto- Burman. Tangkhulic, comparative reconstruction, rhymes, vowel length 1. INTRODUCTION The goal of this paper is to present a preliminary reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic (PT), the ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages of Manipur and contiguous parts of India and Burma. It will show that Proto- Tangkhulic was a relatively conservative daughter language of Proto-Tibeto- Burman, preserving final *-l, and the vowel length distinction (in some contexts), among other features. As such, we suggest that Proto-Tangkhulic has significant importance in understanding the history of Tibeto-Burman. 1.1. The Tangkhulic language family All Tangkhulic languages are spoken in a compact area centered around Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India. -

7112712551213Eokjhjustificati

Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre- Final Alignment construction services in respect of 2 laning of Pallel-Chandel Option Study Report Section of NH- 102C on Engineering, Procurement and Construction mode in the state of Manipur. ALIGNMENT OPTION STUDY 1.1 Prologue National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation (NHIDCL) is a fully owned company of the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRT&H), Government of India. The company promotes, surveys, establishes, design, build, operate, maintain and upgrade National Highways and Strategic Roads including interconnecting roads in parts of the country which share international boundaries with neighboring countrie. The regional connectivity so enhanced would promote cross border trade and commerce and help safeguard India’s international borders. This would lead to the formation of a more integrated and economically consolidated South and South East Asia. In addition, there would be overall economic benefits for the local population and help integrate the peripheral areas with the mainstream in a more robust manner. As a part of the above mentioned endeavor, National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has been entrusted with the assignment of Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning with paved of Pallel-Chandel Section of NH-102C in the state of Manipur. National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. is the employer and executing agency for the consultancy services and the standards of output required from the appointed consultants are of international level both in terms of quality and adherence to the agreed time schedule. -

A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2010 A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language Michelle Arden San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Arden, Michelle, "A Phonetic, Phonological, and Morphosyntactic Analysis of the Mara Language" (2010). Master's Theses. 3744. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.v36r-dk3u https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Linguistics and Language Development San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Michelle J. Arden May 2010 © 2010 Michelle J. Arden ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE by Michelle J. Arden APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Daniel Silverman Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Soteria Svorou Department of Linguistics and Language Development Dr. Kenneth VanBik Department of Linguistics and Language Development ABSTRACT A PHONETIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND MORPHOSYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF THE MARA LANGUAGE by Michelle J. Arden This thesis presents a linguistic analysis of the Mara language, a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in northwest Myanmar and in neighboring districts of India. -

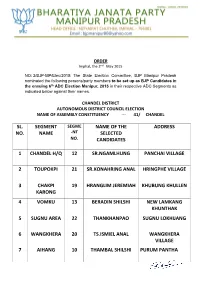

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

EAST TUSOM: a PHONETIC and PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH of a LARGELY UNDOCUMENTED TANGKHULIC LANGUAGE David R

XXXX XXXX — XXXX EAST TUSOM: A PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH OF A LARGELY UNDOCUMENTED TANGKHULIC LANGUAGE David R. Mortensen and Jordan Picone Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh East Tusom is a Tibeto-Burman language of Manipur, India, belonging to the Tangkhulic group. While it shares some innovations with the other Tangkhulic languages, it differs markedly from “Standard Tangkhul” (which is based on the speech of Ukhrul town). Past documentation is limited to a small set of hastily transcribed forms in a comparative reconstruction of Tangkhulic rhymes (Mortensen & Miller 2013; Mortensen 2012). This paper presents the first substantial sketch of an aspect of the language: its (descriptive) phonetics and phonology. The data are based on recordings of an extensive wordlist (730 items) and one short text, all from one fluent native speaker in her mid-twenties. We present the phonetic inventory of East Tusom and a phonemicization, with exhaustive examples. We also present an overview of the major phonological patterns and generalizations in the language. Of special interest are a “placeless nasal” that is realized as nasalization on the preceding vowel unless it is followed by a consonant and numerous plosive-fricative clusters (where the fricative is roughly homorganic with the following vowel) that have developed from historical aspirated plosives. A complete wordlist, organized by gloss and semantic field, is provided as appendices. phonetics; phonology; clusters; placeless nasal; assimilation; language documentation; Tangkhulic INTRODUCTION The East Tusom Language The topic of this paper is the phonetics and phonology of an endangered Tibeto- Burman language spoken in Tusom village, Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India, perhaps in surrounding villages, and by families who have left the area. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels*

John Benjamins Publishing Company This is a contribution from Diachronica 29:4 © 2012. John Benjamins Publishing Company This electronic file may not be altered in any way. The author(s) of this article is/are permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to be used by way of offprints, for their personal use only. Permission is granted by the publishers to post this file on a closed server which is accessible to members (students and staff) only of the author’s/s’ institute, it is not permitted to post this PDF on the open internet. For any other use of this material prior written permission should be obtained from the publishers or through the Copyright Clearance Center (for USA: www.copyright.com). Please contact [email protected] or consult our website: www.benjamins.com Tables of Contents, abstracts and guidelines are available at www.benjamins.com The emergence of obstruents after high vowels* David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh While a few cases of the emergence of obstruents after high vowels are found in the literature (Burling 1966, 1967, Blust 1994), no attempt has been made to comprehensively collect instances of this sound change or give them a unified explanation. This paper attempts to resolve this gap in the literature by introduc- ing a post-vocalic obstruent emergence (POE) as a recurring sound change with a phonetic (aerodynamic) basis. Possible cases are identified in Tibeto-Burman, Austronesian, and Grassfields Bantu. Special attention is given to a novel case in the Tibeto-Burman language Huishu. Keywords: epenthesis, sound change, aerodynamics, exemplar theory, Tibeto- Burman, Austronesian, Niger-Congo 1. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

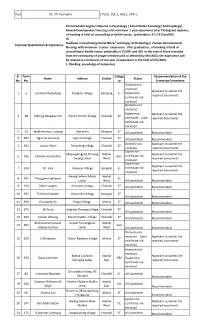

CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Sl. No. Form No. Name Address District Catego Ry Status Recommendation of the Screening Commit

Post A1: STI Counselor 3 Posts: CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Post Graduate degree I diploma in Psychology / Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Nursing; with minimum 1 year experience after PG degree/ diploma, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI / RTI and HIV. Or Graduate in Psychology/Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Essential Qualification & Experience: Nursing; with minimum 3 years .experience after graduation, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI/RTI and HIV. In the case of those recruited from the community of people infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, the experience will be relaxed to a minimum of one year of experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. 1. Working knowledge of computers Sl. Form Catego Recommendation of the Name Address District Status No. No. ry Screening Committee Domicile not enclosed, Applicant to submit the 1 2 Lanmila Khapudang Kongkan Village Kamjong ST Experience required documents certificate not enclosed Domicile not enclosed, Experience Applicant to submit the 2 38 Dilbung Rengwar Eric Purum Pantha Village Chandel ST certificate , Caste required documents certificate not enclosed 3 54 Makhreluibou Luikang Makhrelu Senapati ST All submitted Recommended 4 483 Ngorum Kennedy Japhou Village Chandel ST All submitted Recommended Domicile not Applicant to submit the 5 564 Jacinta Telen Penaching Village Chandel ST enclosed required documents Experience Mayanglangjing Tamang Imphal Applicant to submit the 6 756 -

ORDERS Imphal, the A' April, 2018

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (S) (Administrative Section) ORDERS Imphal, the 17 'April, 2018 No.AO/59/1T(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/20 1 1(4)-DE(S): In supersession of all previous orders issued in this regard, services of the following 95(Ninety-five), Graduate teachers(RMSA) , Upper Primary Teachers(SSA) and Primary Teachers(SSA) are hereby utilised at the school shown against their name with immediate effect in public interest. 2. Consequent upon their utilisation they are hereby released from their present place of posting so as to enable them to join at the new place of utilisation immediately. 3. The Head of Institution concerned should submit a compliance report to the undersigned under intimation to the ZEO concerned. (Th. Kirankumar) Director of Education (S), MaIp1 ' Copy to: 1. PPS to Hon'ble Minister of Education, Manipur. 2. Principal Secretary/Education (S), Government of Manipur. 3. Additional Directors (H/V/PIg.), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 4. Sr. Finance Officer, Edn(S), Manipur 5. Nodal Officer (CPIS), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 6. ZEO concerned. 7. Head of the Institutions concerned. 8. Teacher concerned. 9. Relevant file. Annexure to Order No. AO/59/TT/(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/2011(4)-DE(S) dated 13 Ir April, 2018 EIN Name of the Employee Designation Present Place of Posting Place of Utilisation 1 081054 Premjit Ningthoujam AGT(RMSA) Thamchet H/s CC Hr. Sec. School Chandrakhong Phanjakhong High 2 085756 Keisham Anupama Devi AGT(RMSA) Urup H/S School 3 098662 Konthoujam Sujeta Devi AGT(RMSA) Kasom Khullen H/S Azad Hr. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels 1. Introduction

The Emergence of Obstruents after High Vowels 1. Introduction Vennemann (1988) and others have argued that sound changes which insert segments most commonly do so in a manner that “improves” syllable structure: they provide syllables with onsets, allow consonants that would otherwise be codas to syllabify as onsets, relieve hiatus between vowels, and so on. On the other hand, the deletion of consonants seems to be particularly common in final position, a tendency that is reflected not only in the diachronic mechanisms outlined by Vennemann, but also reified in synchronic mechanisms like the Optimality Theoretic NoCoda constraint (Prince and Smolensky 1993). It may seem surprising, then, that there is small but robust class of sound changes in which obstruents (usually stops, but sometimes fricatives) emerge after word-final vowels. Discussions of individual instances of this phenomenon have periodically appeared in the literature. The best-known case is from Maru (a Tibeto-Burman language closely related to Burmese) and was discovered by Karlgren (1931), Benedict (1948), and Burling (1966; 1967). Ubels (1975) independently noticed epenthetic stops in Grassfields Bantu languages and Stallcup (1978) discussed this development in another Grassfields Bantu language, Moghamo, drawing an explicit parallel to Maru. Blust (1994) presented the most comprehensive treatment of these sound changes to date (in the context of making an argument about the unity of vowel and consonant features). To the Maru case, he added two additional instances from the Austronesian family: Lom (Belom) and Singhi. He also presented two historical scenarios through which these changes could occur: diphthongization and “direct hardening” of the terminus of the vowel.