EAST TUSOM: a PHONETIC and PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH of a LARGELY UNDOCUMENTED TANGKHULIC LANGUAGE David R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R

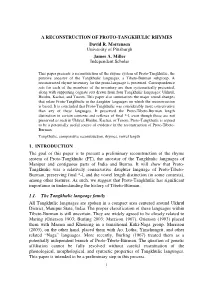

A RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh James A. Miller Independent Scholar This paper presents a reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic, the putative ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages, a Tibeto-Burman subgroup. A reconstructed rhyme inventory for the proto-language is presented. Correspondence sets for each of the members of the inventory are then systematically presented, along with supporting cognate sets drawn from four Tangkhulic languages: Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, and Tusom. This paper also summarizes the major sound changes that relate Proto-Tangkhulic to the daughter languages on which the reconstruction is based. It is concluded that Proto-Tangkhulic was considerably more conservative than any of these languages. It preserved the Proto-Tibeto-Burman length distinction in certain contexts and reflexes of final *-l, even though these are not preserved as such in Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, or Tusom. Proto-Tangkhulic is argued to be a potentially useful source of evidence in the reconstruction of Proto-Tibeto- Burman. Tangkhulic, comparative reconstruction, rhymes, vowel length 1. INTRODUCTION The goal of this paper is to present a preliminary reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic (PT), the ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages of Manipur and contiguous parts of India and Burma. It will show that Proto- Tangkhulic was a relatively conservative daughter language of Proto-Tibeto- Burman, preserving final *-l, and the vowel length distinction (in some contexts), among other features. As such, we suggest that Proto-Tangkhulic has significant importance in understanding the history of Tibeto-Burman. 1.1. The Tangkhulic language family All Tangkhulic languages are spoken in a compact area centered around Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India. -

7112712551213Eokjhjustificati

Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre- Final Alignment construction services in respect of 2 laning of Pallel-Chandel Option Study Report Section of NH- 102C on Engineering, Procurement and Construction mode in the state of Manipur. ALIGNMENT OPTION STUDY 1.1 Prologue National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation (NHIDCL) is a fully owned company of the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRT&H), Government of India. The company promotes, surveys, establishes, design, build, operate, maintain and upgrade National Highways and Strategic Roads including interconnecting roads in parts of the country which share international boundaries with neighboring countrie. The regional connectivity so enhanced would promote cross border trade and commerce and help safeguard India’s international borders. This would lead to the formation of a more integrated and economically consolidated South and South East Asia. In addition, there would be overall economic benefits for the local population and help integrate the peripheral areas with the mainstream in a more robust manner. As a part of the above mentioned endeavor, National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has been entrusted with the assignment of Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning with paved of Pallel-Chandel Section of NH-102C in the state of Manipur. National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. is the employer and executing agency for the consultancy services and the standards of output required from the appointed consultants are of international level both in terms of quality and adherence to the agreed time schedule. -

LIST of FARMERS District : Ukhrul Block : Ukhrul

LIST OF FARMERS District : Ukhrul Block : Ukhrul Card No. Farmer's Name Village/ Block District State Pin no. 447 R. Pamlei Teinem Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 449 Ramreishang Vashi Teinem Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 451 K. Tabitha Ukhrul Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 452 Wisdom Luiyainaotang Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 456 Khaiwonla Kasomtang Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 458 Simlarose Meizailung Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 460 L.S. Wungthing Meizailungtang Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795145 551 A.S. Ningreingam T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 552 A.S. Ngaranmi T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 554 A.S. Thotsem T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 563 A.S. Holy T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 570 A.S. Wonreithing T.Shimin Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 585 A.S. Rock Tashar Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 588 A.S. Shangchuila Tushen Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 589 A.S. Ngamthing Tashar Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 595 A.S. Khaso Tushen Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 598 A.S. Ramshing Tashar Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 404 R.S. Methew longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 405 Chihanpam longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 406 Yursem Awungshi longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 407 S Sareng longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 408 Leishiwon longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 409 L. Shangam longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 410 Joshep Tallanao longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 411 Paoyaola longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 412 Obed Luiram longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 413 T. Yangmi longpi kajui Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 445 K. Horchipei Sirarakhong Ukhrul Ukhrul Manipur 795142 446 R. -

Manipur State Information Technology Society

MANIPUR STATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY SOCIETY (A Government of Manipur Undertaking) 4th Floor, Western Block, New Secretariat, Imphal – 795001 www.msits.gov.in; Email: [email protected] Phone: 0385-24476877 District wise Status of Common Service Centres (As on 25th March, 2013) District: Ukhrul Total No. of CSCs : 33 VSAT Solar Power Sl. CSC Location & VLE Contact District BLOCK CSC Name Name of VLE Installation pack status No Address Number Status 1 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Hundung Hundung K.Y.S Yangmi 9612005006 Installed Installed 2 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Kalhang Kalhang R.S. Michael (Aphung) 9612765614 / Pending Installed 9612130987 3 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Nungshong Nungshong Khullen Ignitius Yaoreiwung 9862883374 Pending Installed Khullen Chithang 4 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangkai Shangkai Chongam Haokip 9612696292 Installed Installed 5 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-New Cannon New Cannon ZS Somila 9862826487 / Installed Installed 9862979109 6 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Jessami Jessami Village Nipekhwe Lohe 9862835841 Pending Installed 7 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Teinem Teinem Mashangam Raleng 8730963043 Pending Installed 8 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Seikhor Seikhor L.A. Pamreiphi 9436243204 / Pending Installed 857855919 / 8731929981 9 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Chingjaroi Chingjaroi Khullen Joyson Tamang 9862992294 Pending Installed Khullen 10 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Litan Litan JS. Aring 9612937524 / Installed Installed 8974425854 / 9436042452 11 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangshak Shangshak khullen R.S. Ngaranmi 9862069769 / Pending Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9436086067 / 9862701697 12 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Lambui Lambui L. Seth 9612489203 / Installed Installed T.D.Block 8974459592 / 9862038398 13 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Kasom Kasom Khullen Shanglai Thangmeichui 9862760611 / Not approved for Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9612320431 VSAT 14 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Khamlang Khamlang N. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels*

John Benjamins Publishing Company This is a contribution from Diachronica 29:4 © 2012. John Benjamins Publishing Company This electronic file may not be altered in any way. The author(s) of this article is/are permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to be used by way of offprints, for their personal use only. Permission is granted by the publishers to post this file on a closed server which is accessible to members (students and staff) only of the author’s/s’ institute, it is not permitted to post this PDF on the open internet. For any other use of this material prior written permission should be obtained from the publishers or through the Copyright Clearance Center (for USA: www.copyright.com). Please contact [email protected] or consult our website: www.benjamins.com Tables of Contents, abstracts and guidelines are available at www.benjamins.com The emergence of obstruents after high vowels* David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh While a few cases of the emergence of obstruents after high vowels are found in the literature (Burling 1966, 1967, Blust 1994), no attempt has been made to comprehensively collect instances of this sound change or give them a unified explanation. This paper attempts to resolve this gap in the literature by introduc- ing a post-vocalic obstruent emergence (POE) as a recurring sound change with a phonetic (aerodynamic) basis. Possible cases are identified in Tibeto-Burman, Austronesian, and Grassfields Bantu. Special attention is given to a novel case in the Tibeto-Burman language Huishu. Keywords: epenthesis, sound change, aerodynamics, exemplar theory, Tibeto- Burman, Austronesian, Niger-Congo 1. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Sl. No. Form No. Name Address District Catego Ry Status Recommendation of the Screening Commit

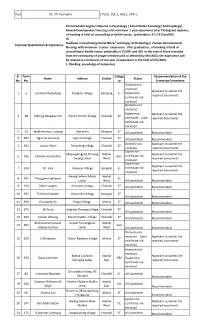

Post A1: STI Counselor 3 Posts: CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Post Graduate degree I diploma in Psychology / Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Nursing; with minimum 1 year experience after PG degree/ diploma, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI / RTI and HIV. Or Graduate in Psychology/Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Essential Qualification & Experience: Nursing; with minimum 3 years .experience after graduation, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI/RTI and HIV. In the case of those recruited from the community of people infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, the experience will be relaxed to a minimum of one year of experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. 1. Working knowledge of computers Sl. Form Catego Recommendation of the Name Address District Status No. No. ry Screening Committee Domicile not enclosed, Applicant to submit the 1 2 Lanmila Khapudang Kongkan Village Kamjong ST Experience required documents certificate not enclosed Domicile not enclosed, Experience Applicant to submit the 2 38 Dilbung Rengwar Eric Purum Pantha Village Chandel ST certificate , Caste required documents certificate not enclosed 3 54 Makhreluibou Luikang Makhrelu Senapati ST All submitted Recommended 4 483 Ngorum Kennedy Japhou Village Chandel ST All submitted Recommended Domicile not Applicant to submit the 5 564 Jacinta Telen Penaching Village Chandel ST enclosed required documents Experience Mayanglangjing Tamang Imphal Applicant to submit the 6 756 -

ORDERS Imphal, the A' April, 2018

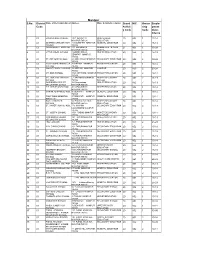

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (S) (Administrative Section) ORDERS Imphal, the 17 'April, 2018 No.AO/59/1T(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/20 1 1(4)-DE(S): In supersession of all previous orders issued in this regard, services of the following 95(Ninety-five), Graduate teachers(RMSA) , Upper Primary Teachers(SSA) and Primary Teachers(SSA) are hereby utilised at the school shown against their name with immediate effect in public interest. 2. Consequent upon their utilisation they are hereby released from their present place of posting so as to enable them to join at the new place of utilisation immediately. 3. The Head of Institution concerned should submit a compliance report to the undersigned under intimation to the ZEO concerned. (Th. Kirankumar) Director of Education (S), MaIp1 ' Copy to: 1. PPS to Hon'ble Minister of Education, Manipur. 2. Principal Secretary/Education (S), Government of Manipur. 3. Additional Directors (H/V/PIg.), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 4. Sr. Finance Officer, Edn(S), Manipur 5. Nodal Officer (CPIS), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 6. ZEO concerned. 7. Head of the Institutions concerned. 8. Teacher concerned. 9. Relevant file. Annexure to Order No. AO/59/TT/(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/2011(4)-DE(S) dated 13 Ir April, 2018 EIN Name of the Employee Designation Present Place of Posting Place of Utilisation 1 081054 Premjit Ningthoujam AGT(RMSA) Thamchet H/s CC Hr. Sec. School Chandrakhong Phanjakhong High 2 085756 Keisham Anupama Devi AGT(RMSA) Urup H/S School 3 098662 Konthoujam Sujeta Devi AGT(RMSA) Kasom Khullen H/S Azad Hr. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels 1. Introduction

The Emergence of Obstruents after High Vowels 1. Introduction Vennemann (1988) and others have argued that sound changes which insert segments most commonly do so in a manner that “improves” syllable structure: they provide syllables with onsets, allow consonants that would otherwise be codas to syllabify as onsets, relieve hiatus between vowels, and so on. On the other hand, the deletion of consonants seems to be particularly common in final position, a tendency that is reflected not only in the diachronic mechanisms outlined by Vennemann, but also reified in synchronic mechanisms like the Optimality Theoretic NoCoda constraint (Prince and Smolensky 1993). It may seem surprising, then, that there is small but robust class of sound changes in which obstruents (usually stops, but sometimes fricatives) emerge after word-final vowels. Discussions of individual instances of this phenomenon have periodically appeared in the literature. The best-known case is from Maru (a Tibeto-Burman language closely related to Burmese) and was discovered by Karlgren (1931), Benedict (1948), and Burling (1966; 1967). Ubels (1975) independently noticed epenthetic stops in Grassfields Bantu languages and Stallcup (1978) discussed this development in another Grassfields Bantu language, Moghamo, drawing an explicit parallel to Maru. Blust (1994) presented the most comprehensive treatment of these sound changes to date (in the context of making an argument about the unity of vowel and consonant features). To the Maru case, he added two additional instances from the Austronesian family: Lom (Belom) and Singhi. He also presented two historical scenarios through which these changes could occur: diphthongization and “direct hardening” of the terminus of the vowel. -

GOVT. SCHOOLS Type of School Rural/ Sl

LIST OF SCHOOLS ( As on 30th September, 2015 ) GOVT. SCHOOLS Type of School Rural/ Sl. Class Managemen Name of School Boys/ Address Urban Constituency Block Remarks No. Structure t Girls/ (R/U) Co-Edn 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 HIGHER SECONDARY Schools in CPIS ( ZEO - Bishnupur ) 1 Bishnupur Higher Secondary School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Bishnupur Ward No.6 Urban Bishnupur BM Bishnupur Hr./Sec Nambol Hr./Sec, Nambol 2 Nambolg Higherp Secondary p School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Nambol Ward No. 3 Urban Nambol NM 3 Higher Secondary School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Moirang Lamkhai Urban Moirang MM Moirang Multipurpose Hr./Sec Schools in CPIS ZEO Imphal- East 1 Ananda Singh Hr.Sec. School IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. khumunnom Urban Wangkhei IMC Ananda Singh Hr./Sec Academy 2 Churachand Hr.Sec. School IX-XII Edn Dept Boys Palace Gate Urban Yaiskul IMC C.C. Higher Sec. School 3 Lamlong Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Khurai Thoudam Lk. Urban Wangkhei IMC Lamlong Hr./Sec 4 Azad Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Yairipok Tulihal Rural Andro I- E -II Azad High School, Yairipok 5 Sagolmang Hr.Sec. School VI-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Sagolmang Rural Khundrakpam I- E -I Sagolmang Govt. H/S. ( ZEO-Jiribam) 1 Jiribam Higher Secondary IX-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Babupara Jiribam Urban Jiribam JM Jiribam Hr./Sec 2 Borobekara Hr.Sec. III-XII Edn Dept Co-Edn. Borobekara Rural Jiribam Jiribam Borobekra Hr. -

Manipur S.No

Manipur S.No. District Name of the Establishment Address Major Activity Description Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Activit ship yment y Code Code Class Interva l 101OKLONG HIGH SCHOOL 120/1 SENAPATI HIGH SCHOOL 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795104 EDUCATION 201BETHANY ENGLISH HIGH 149 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795104 301GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL 125 MAKHRALUI HUMAN HEALTH CARE 21 861 1 30-99 MANIPUR 795104 CENTRE 401LITTLE ANGEL SCHOOL 132 MAKHRELUI, HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SENAPATI MANIPUR 795106 501ST. ANTHONY SCHOOL 28 MAKHRELUI MANIPUR SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 30-99 795106 601TUSII NGAINI KHUMAI UJB 30 MEITHAI MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 1 10-14 SCHOOL 795106 701MOUNT PISGAH COLLEGE 14 MEITHAI MANIPUR COLLEGE 20 853 2 20-24 795106 801MT. ZION SCHOOL 47(2) KATHIKHO MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 2 10-14 795106 901MT. ZION ENGLISH HIGH 52 KATHIKHO MANIPUR HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795106 SCHOOL 10 01 DON BOSCO HIGHER 38 Chingmeirong HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 7 15-19 SECONDARY SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 11 01 P.P. CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 40 LAIROUCHING HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795105 12 01 MARAM ASHRAM SCHOOL 86 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 795105 13 01 RANGTAIBA MEMORIAL 97 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 853 1 10-14 INSTITUTE 795105 14 01 SAINT VINCENT'S 94 PUNGDUNGLUNG HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 10-14 SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 EDUCATION 15 01 ST. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL 179 MAKHAN SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 LOVADZINHO MANIPUR 795105 16 01 ST. -

Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District 2014

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 2014 DISTRICT STATISTICAL OFFICE, UKHRUL DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR PREFACE The present issue of ‘Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District, 2014’ is the 8th series of the publication earlier entitled „Statistical Abstract of Ukhrul District, 2007‟. It presents the latest available numerical information pertaining to various socio-economic aspects of Ukhrul District. Most of the data presented in this issue are collected from various Government Department/ Offices/Local bodies. The generous co-operation extended by different Departments/Offices/ Statutory bodies in furnishing the required data is gratefully acknowledged. The sincere efforts put in by Shri N. Hongva Shimray, District Statistical Officer and staffs who are directly and indirectly responsible in bringing out the publications are also acknowledged. Suggestions for improvement in the quality and coverage in its future issues of the publication are most welcome. Dated, Imphal Peijonna Kamei The 4th June, 2015 Director of Economics & Statistics Manipur. C O N T E N T S Table Page Item No. No. 1. GENERAL PARTICULARS OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 1 2. AREA AND POPULATION 2.1 Area and Density of Population of Manipur by Districts, 2011 Census. 1 2.2 Population of Manipur by Sector, Sex and Districts according to 2011 2 Census 2.3 District wise Sex Ratio of Manipur according to Population Censuses 2 2.4 Sub-Division-wise Population and Decadal Growth rate of Ukhrul 3 District 2.5 Population of Ukhrul District by Sex 3 2.6 Sub-Division-wise Population in the age group 0-6 of Ukhrul District by sex according to 2011 census 4 2.7 Number of Literates and Literacy Rate by Sex in Ukhrul District 4 2.8 Workers and Non-workers of Ukhrul District by sex, 2001 and 2011 5 censuses 3.