A RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

National E-Conference on Naga Languages and Culture

National e-Conference on Naga Languages and Culture Organized by: Centre for Naga Tribal Language Studies (CNTLS) Nagaland University, Kohima Campus, Meriema-797004, India DATES: 8th-10th October, 2020 The Centre for Naga Tribal Language Studies (CNTLS), Nagaland University, Kohima Campus, Meriema is organizing a 3-Day National E-Conference on various aspects of Naga Languages and Culture from 8th–10th October, 2020. Concept Note “Language is the road map of a culture. It tells you where its people come from and where they are going.” Rita Mae Brown. Inarguably the most diversified group of languages in India, Naga languages, spoken by Naga tribes native to Nagaland and parts of Manipur, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh – all North East Indian States – and Myanmar country, constitute a unique and distinct class in itself. No other language has been found to subsume within itself a number and variety of fundamentally distinct languages/dialects as ours. For example, Nagaland, a small state with a geographical area of 16, 579 sq km and a population of nearly 2 million as per 2011 census alone has 14 ‘officially’ recognized indigenous Naga languages but a much larger, albeit officially unrecognized, number of constituent languages/dialects intertwined within those languages, making it a linguistically rich and diverse state. There are so many languages, dialects and sub-dialects among the speakers of a particular language community that it is almost as if every village has a dialect of its own. To illustrate further, the Konyak language itself has more than 20 dialects, the Pochury at least 8, the Phom at least 5, the Chakhesang 3, the Angami 4, the Ao 3 and so on. -

7112712551213Eokjhjustificati

Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre- Final Alignment construction services in respect of 2 laning of Pallel-Chandel Option Study Report Section of NH- 102C on Engineering, Procurement and Construction mode in the state of Manipur. ALIGNMENT OPTION STUDY 1.1 Prologue National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation (NHIDCL) is a fully owned company of the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRT&H), Government of India. The company promotes, surveys, establishes, design, build, operate, maintain and upgrade National Highways and Strategic Roads including interconnecting roads in parts of the country which share international boundaries with neighboring countrie. The regional connectivity so enhanced would promote cross border trade and commerce and help safeguard India’s international borders. This would lead to the formation of a more integrated and economically consolidated South and South East Asia. In addition, there would be overall economic benefits for the local population and help integrate the peripheral areas with the mainstream in a more robust manner. As a part of the above mentioned endeavor, National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has been entrusted with the assignment of Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning with paved of Pallel-Chandel Section of NH-102C in the state of Manipur. National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. is the employer and executing agency for the consultancy services and the standards of output required from the appointed consultants are of international level both in terms of quality and adherence to the agreed time schedule. -

Peopling the Northeast: Part 5

54 neScholar 0 vol 3 0 issue 3 Peopling of the Northeast Tanmoy Bhattacharya Teaches at Centre of Part 5 Advanced Studies in Linguistics Faculty of Arts, University of Delhi & Chief Editor of Indian Linguistics S I was returning from the 23rd version of during the Air-India flight from Guwahati to Delhi, when the Himalayan Languages Symposium, my teacher and ex-colleague from the University of Delhi held from 5th to 7th July, I had this and a well known expert on Tibeto-Burman linguistics, nagging feeling that I am not yet done Prof.K.V.Subbarao, who thinks of and analyses linguistic with the story of peopling of the data even in his sleep, sitting across the aisle, expressed Northeast of India, published in four his surprise at many young scholars classifying Meeteilon instalments in the previous four issues of this increasingly in the Kuki-Chin subgroup of Tibeto-Burman, in several popularA journal (see vol. 2, issues 3-4, 2016; and vol. talks in the Symposium. 3, issues 1-2, 2017). My hunch was confirmed and transformed into an overlapping series of echoes of bells N fact, more than a century ago, the visionary linguist ringing in the ancient corridors of history, as soon as the IGeorge Abraham Grierson had the same doubt as early seat-belt signs were turned off after reaching 20,000 feet as 1904: 54 neScholar 0 vol 3 0 issue 3 neScholar 0 vol 3 0 issue 2 55 PEOPLING OF NE INDIA I HERITAGE “The Kuki-Chin languages must be subdivided in issue better. -

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

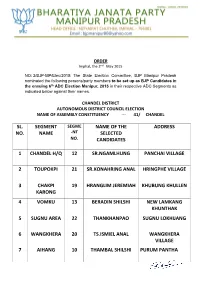

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

AO and PROTO-TIBETO-BURMAN – the RIMES* Daniel Bruhn University of California, Berkeley

Format adapted from the LTBA stylesheet UCB Linguistics Qualifying Paper #2 Revised: 27 October 2010 UNEARTHING THE ROOTS: AO AND PROTO-TIBETO-BURMAN – THE RIMES* Daniel Bruhn University of California, Berkeley Keywords: Tibeto-Burman, historical, linguistics, Naga, Mongsen, Chungli, Ao, reflexes, roots, cognate sets, sound correspondences, sound change Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 2 1.1. Purpose ................................................................................................................. 2 1.2. Background ........................................................................................................... 3 1.3. Phonology ............................................................................................................. 4 1.3.1. Chungli ........................................................................................................... 4 1.3.2. Mongsen ......................................................................................................... 7 1.4. Methodology ......................................................................................................... 9 2. RIMES ....................................................................................................................... 11 2.1. *-a- ..................................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1. *-a > Chungli -a/-u/-i, Mongsen -a ........................................................... -

EAST TUSOM: a PHONETIC and PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH of a LARGELY UNDOCUMENTED TANGKHULIC LANGUAGE David R

XXXX XXXX — XXXX EAST TUSOM: A PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH OF A LARGELY UNDOCUMENTED TANGKHULIC LANGUAGE David R. Mortensen and Jordan Picone Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh East Tusom is a Tibeto-Burman language of Manipur, India, belonging to the Tangkhulic group. While it shares some innovations with the other Tangkhulic languages, it differs markedly from “Standard Tangkhul” (which is based on the speech of Ukhrul town). Past documentation is limited to a small set of hastily transcribed forms in a comparative reconstruction of Tangkhulic rhymes (Mortensen & Miller 2013; Mortensen 2012). This paper presents the first substantial sketch of an aspect of the language: its (descriptive) phonetics and phonology. The data are based on recordings of an extensive wordlist (730 items) and one short text, all from one fluent native speaker in her mid-twenties. We present the phonetic inventory of East Tusom and a phonemicization, with exhaustive examples. We also present an overview of the major phonological patterns and generalizations in the language. Of special interest are a “placeless nasal” that is realized as nasalization on the preceding vowel unless it is followed by a consonant and numerous plosive-fricative clusters (where the fricative is roughly homorganic with the following vowel) that have developed from historical aspirated plosives. A complete wordlist, organized by gloss and semantic field, is provided as appendices. phonetics; phonology; clusters; placeless nasal; assimilation; language documentation; Tangkhulic INTRODUCTION The East Tusom Language The topic of this paper is the phonetics and phonology of an endangered Tibeto- Burman language spoken in Tusom village, Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India, perhaps in surrounding villages, and by families who have left the area. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels*

John Benjamins Publishing Company This is a contribution from Diachronica 29:4 © 2012. John Benjamins Publishing Company This electronic file may not be altered in any way. The author(s) of this article is/are permitted to use this PDF file to generate printed copies to be used by way of offprints, for their personal use only. Permission is granted by the publishers to post this file on a closed server which is accessible to members (students and staff) only of the author’s/s’ institute, it is not permitted to post this PDF on the open internet. For any other use of this material prior written permission should be obtained from the publishers or through the Copyright Clearance Center (for USA: www.copyright.com). Please contact [email protected] or consult our website: www.benjamins.com Tables of Contents, abstracts and guidelines are available at www.benjamins.com The emergence of obstruents after high vowels* David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh While a few cases of the emergence of obstruents after high vowels are found in the literature (Burling 1966, 1967, Blust 1994), no attempt has been made to comprehensively collect instances of this sound change or give them a unified explanation. This paper attempts to resolve this gap in the literature by introduc- ing a post-vocalic obstruent emergence (POE) as a recurring sound change with a phonetic (aerodynamic) basis. Possible cases are identified in Tibeto-Burman, Austronesian, and Grassfields Bantu. Special attention is given to a novel case in the Tibeto-Burman language Huishu. Keywords: epenthesis, sound change, aerodynamics, exemplar theory, Tibeto- Burman, Austronesian, Niger-Congo 1. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

Asho Daniel Tignor

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2018 A Phonology Of Hill (kone-Tu) Asho Daniel Tignor Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Tignor, Daniel, "A Phonology Of Hill (kone-Tu) Asho" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2364. https://commons.und.edu/theses/2364 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHONOLOGY OF HILL (KONE-TU) ASHO by Daniel Tignor Bachelor of Science, Harding University, 2005 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota August 2018 i PERMISSION Title A Phonology of Hill (Kone-Tu) Asho Department Linguistics Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the University of North Dakota, I agree that the library of this University shall make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for extensive copying for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor who supervised my thesis work or, in his absence, by the chairperson of the department or the dean of the Graduate School. It is understood that any copying or publication or other use of this thesis or part thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

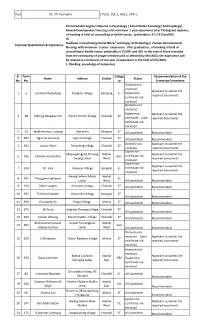

CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Sl. No. Form No. Name Address District Catego Ry Status Recommendation of the Screening Commit

Post A1: STI Counselor 3 Posts: CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Post Graduate degree I diploma in Psychology / Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Nursing; with minimum 1 year experience after PG degree/ diploma, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI / RTI and HIV. Or Graduate in Psychology/Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Essential Qualification & Experience: Nursing; with minimum 3 years .experience after graduation, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI/RTI and HIV. In the case of those recruited from the community of people infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, the experience will be relaxed to a minimum of one year of experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. 1. Working knowledge of computers Sl. Form Catego Recommendation of the Name Address District Status No. No. ry Screening Committee Domicile not enclosed, Applicant to submit the 1 2 Lanmila Khapudang Kongkan Village Kamjong ST Experience required documents certificate not enclosed Domicile not enclosed, Experience Applicant to submit the 2 38 Dilbung Rengwar Eric Purum Pantha Village Chandel ST certificate , Caste required documents certificate not enclosed 3 54 Makhreluibou Luikang Makhrelu Senapati ST All submitted Recommended 4 483 Ngorum Kennedy Japhou Village Chandel ST All submitted Recommended Domicile not Applicant to submit the 5 564 Jacinta Telen Penaching Village Chandel ST enclosed required documents Experience Mayanglangjing Tamang Imphal Applicant to submit the 6 756 -

ORDERS Imphal, the A' April, 2018

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (S) (Administrative Section) ORDERS Imphal, the 17 'April, 2018 No.AO/59/1T(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/20 1 1(4)-DE(S): In supersession of all previous orders issued in this regard, services of the following 95(Ninety-five), Graduate teachers(RMSA) , Upper Primary Teachers(SSA) and Primary Teachers(SSA) are hereby utilised at the school shown against their name with immediate effect in public interest. 2. Consequent upon their utilisation they are hereby released from their present place of posting so as to enable them to join at the new place of utilisation immediately. 3. The Head of Institution concerned should submit a compliance report to the undersigned under intimation to the ZEO concerned. (Th. Kirankumar) Director of Education (S), MaIp1 ' Copy to: 1. PPS to Hon'ble Minister of Education, Manipur. 2. Principal Secretary/Education (S), Government of Manipur. 3. Additional Directors (H/V/PIg.), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 4. Sr. Finance Officer, Edn(S), Manipur 5. Nodal Officer (CPIS), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 6. ZEO concerned. 7. Head of the Institutions concerned. 8. Teacher concerned. 9. Relevant file. Annexure to Order No. AO/59/TT/(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/2011(4)-DE(S) dated 13 Ir April, 2018 EIN Name of the Employee Designation Present Place of Posting Place of Utilisation 1 081054 Premjit Ningthoujam AGT(RMSA) Thamchet H/s CC Hr. Sec. School Chandrakhong Phanjakhong High 2 085756 Keisham Anupama Devi AGT(RMSA) Urup H/S School 3 098662 Konthoujam Sujeta Devi AGT(RMSA) Kasom Khullen H/S Azad Hr.