The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Test for Exemplar Theory: Varying Versus Non-Varying General Linguistics Glossa Words in Spanish

a journal of Pycha, Anne. 2017. A new test for exemplar theory: Varying versus non-varying general linguistics Glossa words in Spanish. Glossa: a journal of general linguistics 2(1): 82. 1–31, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/gjgl.240 RESEARCH A new test for exemplar theory: Varying versus non-varying words in Spanish Anne Pycha University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, US [email protected] We used a Deese-Roediger-McDermott false memory paradigm to compare Spanish words in which the phonetic realization of /s/ can vary (word-medial positions: bu[s]to ~ bu[h]to ‘chest’, word-final positions:remo [s] ~ remo[h] ‘oars’) to words in which it cannot (word-initial positions: [s]opa ~ *[h]opa ‘soup’). At study, participants listened to lists of nine words that were phonological neighbors of an unheard critical item (e.g., popa, sepa, soja, etc. for the critical item sopa). At test, participants performed free recall and yes/no recognition tasks. Replicating previous work in this paradigm, results showed robust false memory effects: that is, participants were more likely to (falsely) remember a critical item than a random intrusion. When the realization of /s/ was consistent across conditions (Experiment 1), false memory rates for varying versus non-varying words did not significantly differ. However, when the realization of /s/ varied between [s] and [h] in those positions which allow it (Experiment 2), false recognition rates for varying words like busto were significantly higher than those for non-varying words likesopa . Assuming that higher false memory rates are indicative of greater lexical activation, we interpret these results to support the predictions of exemplar theory, which claims that words with heterogeneous versus homogeneous acoustic realizations should exhibit distinct patterns of activation. -

A RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R

A RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh James A. Miller Independent Scholar This paper presents a reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic, the putative ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages, a Tibeto-Burman subgroup. A reconstructed rhyme inventory for the proto-language is presented. Correspondence sets for each of the members of the inventory are then systematically presented, along with supporting cognate sets drawn from four Tangkhulic languages: Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, and Tusom. This paper also summarizes the major sound changes that relate Proto-Tangkhulic to the daughter languages on which the reconstruction is based. It is concluded that Proto-Tangkhulic was considerably more conservative than any of these languages. It preserved the Proto-Tibeto-Burman length distinction in certain contexts and reflexes of final *-l, even though these are not preserved as such in Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, or Tusom. Proto-Tangkhulic is argued to be a potentially useful source of evidence in the reconstruction of Proto-Tibeto- Burman. Tangkhulic, comparative reconstruction, rhymes, vowel length 1. INTRODUCTION The goal of this paper is to present a preliminary reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic (PT), the ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages of Manipur and contiguous parts of India and Burma. It will show that Proto- Tangkhulic was a relatively conservative daughter language of Proto-Tibeto- Burman, preserving final *-l, and the vowel length distinction (in some contexts), among other features. As such, we suggest that Proto-Tangkhulic has significant importance in understanding the history of Tibeto-Burman. 1.1. The Tangkhulic language family All Tangkhulic languages are spoken in a compact area centered around Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India. -

7112712551213Eokjhjustificati

Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre- Final Alignment construction services in respect of 2 laning of Pallel-Chandel Option Study Report Section of NH- 102C on Engineering, Procurement and Construction mode in the state of Manipur. ALIGNMENT OPTION STUDY 1.1 Prologue National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation (NHIDCL) is a fully owned company of the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRT&H), Government of India. The company promotes, surveys, establishes, design, build, operate, maintain and upgrade National Highways and Strategic Roads including interconnecting roads in parts of the country which share international boundaries with neighboring countrie. The regional connectivity so enhanced would promote cross border trade and commerce and help safeguard India’s international borders. This would lead to the formation of a more integrated and economically consolidated South and South East Asia. In addition, there would be overall economic benefits for the local population and help integrate the peripheral areas with the mainstream in a more robust manner. As a part of the above mentioned endeavor, National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has been entrusted with the assignment of Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning with paved of Pallel-Chandel Section of NH-102C in the state of Manipur. National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. is the employer and executing agency for the consultancy services and the standards of output required from the appointed consultants are of international level both in terms of quality and adherence to the agreed time schedule. -

Vowel Breaking Publicat a Diccionari De Lingüística on Line (

Diccionari de lingüística online | Ciències del llenguatge i docència (Grup d'Innovació Docent UB) Page 1 of 3 Vowel breaking Publicat a Diccionari de lingüística on line (http://www.ub.edu/diccionarilinguistica) Vowel breaking Data d'edició: 17 de Abril de 2013 Autoria: Emilia Castaño Revisió: Ignasi Adiego Vowel breaking is a sound change whereby a single vowel changes to become a diphthong in specific environments. The resulting sound preserves the original vowel, which is either preceded or followed by a glide. This process is manifested in a variety of Germanic languages and is characteristic of Old English. Contents Explanation Related concepts Basic bibliography Additional bibliography Explanation In historical linguistics vowel breaking is defined as an assimilatory sound change that implies the diphthongization of single vowels due to the influence of a neighboring sound. The first segment of the resulting diphthong coincides with the original vowel whereas the second is a glide the articulatory characteristics of which are determined by the triggering sound. This process is well attested in Old English where certain front vowels, /æ/ /e/ and /i/, in their short and long variants, were diphthongized when immediately followed by a velar /x/ or a cluster containing a velarized consonant and /?/ or /r/, as its first element. /æ/ > /æu/ / ___ /x/ /æ/ > /æu/ / ___ /?/ or /r + C /e/ > /eu/ / ___ /x/ /e/ > /eu/ / ___ /?/ or /r + C /i/ > /iu/ / ___ /x/ /i/ > /iu/ / ___ /?/ or /r + C In this context, the glide appeared as a transition sound in response to the tongue movements performed when articulating the vowels at the front of the mouth and the consonants at the back of the mouth. -

Segmental Patterns and Phonological Asymmetries in English Loans in Hugariyyah Yemeni Arabic (HYA): an OT Account

Interdisciplinary Journal of Linguistics (IJL Vol.11) Interdisciplinary Journal of Linguistics Volume [11] 2018, Pp.106-118 Segmental Patterns and Phonological Asymmetries in English Loans in Hugariyyah Yemeni Arabic (HYA): An OT Account Yasmeen Yaseen * Hemanga Dutta * Abstract This paper intends to focus on the notion of segmental patterns registered across the English loan words in Yemeni Arabic of Hugariyyah variety. The adaptation process of loanwords in HYA conforms to the structural constraints of Arabic Phonology. During the process of adaptation onset positions are treated as more salient than coda positions. Deletion is not allowed in onset position and the ranking schemata is ONS>>*Complex >> Max >> SSP >> *Coda. In the similar fashion devoicing of the voiced obstruents is mere favourable in coda positions. In HYA English loanwords, the segments which are less salient and less sonorants are altered or deleted than their stronger counterparts in coda positions which support the accepted claim of positional faithfulness to the onset. The paper seeks to address whether idiosyncratic patterns displayed by loans in HYA supports the notion of the positional asymmetries and phonological strength in the loanwords. Furthermore, it provides reasons for the adaptation using the Optimality- Theoretic framework (Prince & Smolensky, 1993, McCarthy & Prince, 1995). Key Words: Segmental Patterns, Loanwords, Positional Faithfulness Introduction This paper is an attempt at representing the segmental patterning and phonological asymmetries within the phonological patterns of English loanwords in Yemeni Arabic of Hugariyyah. It is to examine what happens to English loanwords after lexical borrowing occurs in HYA. Borrowing of lexical items not only results in the enrichment of the lexical inventory of HYA, but also leads to a variety of changes to English borrowed words. -

Phonetic Enhancement and Three Patterns of English A-Tensing

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 23 Issue 1 Proceedings of the 40th Annual Penn Article 21 Linguistics Conference 2017 Phonetic Enhancement and Three Patterns of English a-Tensing Yining Nie New York University Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Nie, Yining (2017) "Phonetic Enhancement and Three Patterns of English a-Tensing," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 21. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol23/iss1/21 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol23/iss1/21 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Phonetic Enhancement and Three Patterns of English a-Tensing Abstract English a-tensing has received numerous treatments in the phonological and sociolinguistic literature, but the question of why it occurs (i) at all and (ii) in seemingly unnatural disjunctive phonological environments has not been settled. This paper presents a novel phonetic enhancement account of a-tensing in Philadelphia, New York City and Belfast English. I propose that a-tensing is best understood as an allophonic process which facilitates the perceptual identity and articulatory ease of nasality, voicing and/or segment duration in the following consonant. This approach unifies the apparently unnatural phonological environments in which the two a variants surface and predicts the attested dialectal patterns. A synchronic account of a-tensing also provides -

Peering Into the Obstruent-Sonorant Divide: the View from /V

Peering into the obstruent-sonorant divide: The view from /v/ Christina Bjorndahl May 04, 2018 Cornell University, PhD Candidate Carnegie Mellon University, Visiting Scholar 1 Why /v/? Final Devoicing: /v/ → [f] / __# 4) [prava] [praf] ‘right (fem./masc.)’ Russian /v/: Final Devoicing Final Devoicing: /D/ → [T] /__# 1) [sleda] [slet] ‘track (gen./nom.sg)’ 2) [soka] [sok] ‘juice (gen./nom.sg)’ 3) [mil] *[mil] ‘dear’ ˚ 2 Russian /v/: Final Devoicing Final Devoicing: /D/ → [T] /__# 1) [sleda] [slet] ‘track (gen./nom.sg)’ 2) [soka] [sok] ‘juice (gen./nom.sg)’ 3) [mil] *[mil] ‘dear’ ˚ Final Devoicing: /v/ → [f] / __# 4) [prava] [praf] ‘right (fem./masc.)’ 2 Regressive Voicing Assimilation: /v/ → [f] / __T 9) /v ruke/ [v ruke] ‘in one’s hand’ 10) /v gorode/ [v gorode] ‘in the city’ 11) /v supe/ [f supe] ‘in the soup’ Russian /v/: Regressive Voicing Assimilation Regressive Voicing Assimilation: /D/ → [T] / __T 5) /pod-nesti/ [podnesti] ‘to bring (to)’ 6) /pod-ZetS/ [podZetS] ‘to set fire to’ 7) /pod-pisatj/ [potpisatj] ‘to sign’ 8) [volk] *[volk] ‘wolf’ ˚ 3 Russian /v/: Regressive Voicing Assimilation Regressive Voicing Assimilation: /D/ → [T] / __T 5) /pod-nesti/ [podnesti] ‘to bring (to)’ 6) /pod-ZetS/ [podZetS] ‘to set fire to’ 7) /pod-pisatj/ [potpisatj] ‘to sign’ 8) [volk] *[volk] ‘wolf’ ˚ Regressive Voicing Assimilation: /v/ → [f] / __T 9) /v ruke/ [v ruke] ‘in one’s hand’ 10) /v gorode/ [v gorode] ‘in the city’ 11) /v supe/ [f supe] ‘in the soup’ 3 Regressive Voicing Assimilation: /T/ 9 [D] / __v 15) /ot-vesti/ [otvesti] ‘lead away’ *[odvesti] -

EAST TUSOM: a PHONETIC and PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH of a LARGELY UNDOCUMENTED TANGKHULIC LANGUAGE David R

XXXX XXXX — XXXX EAST TUSOM: A PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL SKETCH OF A LARGELY UNDOCUMENTED TANGKHULIC LANGUAGE David R. Mortensen and Jordan Picone Carnegie Mellon University and University of Pittsburgh East Tusom is a Tibeto-Burman language of Manipur, India, belonging to the Tangkhulic group. While it shares some innovations with the other Tangkhulic languages, it differs markedly from “Standard Tangkhul” (which is based on the speech of Ukhrul town). Past documentation is limited to a small set of hastily transcribed forms in a comparative reconstruction of Tangkhulic rhymes (Mortensen & Miller 2013; Mortensen 2012). This paper presents the first substantial sketch of an aspect of the language: its (descriptive) phonetics and phonology. The data are based on recordings of an extensive wordlist (730 items) and one short text, all from one fluent native speaker in her mid-twenties. We present the phonetic inventory of East Tusom and a phonemicization, with exhaustive examples. We also present an overview of the major phonological patterns and generalizations in the language. Of special interest are a “placeless nasal” that is realized as nasalization on the preceding vowel unless it is followed by a consonant and numerous plosive-fricative clusters (where the fricative is roughly homorganic with the following vowel) that have developed from historical aspirated plosives. A complete wordlist, organized by gloss and semantic field, is provided as appendices. phonetics; phonology; clusters; placeless nasal; assimilation; language documentation; Tangkhulic INTRODUCTION The East Tusom Language The topic of this paper is the phonetics and phonology of an endangered Tibeto- Burman language spoken in Tusom village, Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India, perhaps in surrounding villages, and by families who have left the area. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

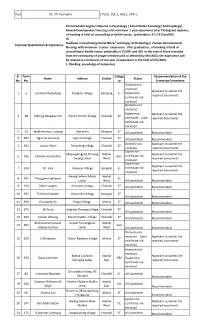

CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Sl. No. Form No. Name Address District Catego Ry Status Recommendation of the Screening Commit

Post A1: STI Counselor 3 Posts: CDL-1, UKL-1, SNP-1 Post Graduate degree I diploma in Psychology / Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Nursing; with minimum 1 year experience after PG degree/ diploma, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI / RTI and HIV. Or Graduate in Psychology/Social Work/ Sociology/ Anthropology/ Human Development/ Essential Qualification & Experience: Nursing; with minimum 3 years .experience after graduation, of working in field of counselling in health sector; preferably in STI/RTI and HIV. In the case of those recruited from the community of people infected with or affected by HIV/AIDS, the experience will be relaxed to a minimum of one year of experience in the field of HIV/AIDS. 1. Working knowledge of computers Sl. Form Catego Recommendation of the Name Address District Status No. No. ry Screening Committee Domicile not enclosed, Applicant to submit the 1 2 Lanmila Khapudang Kongkan Village Kamjong ST Experience required documents certificate not enclosed Domicile not enclosed, Experience Applicant to submit the 2 38 Dilbung Rengwar Eric Purum Pantha Village Chandel ST certificate , Caste required documents certificate not enclosed 3 54 Makhreluibou Luikang Makhrelu Senapati ST All submitted Recommended 4 483 Ngorum Kennedy Japhou Village Chandel ST All submitted Recommended Domicile not Applicant to submit the 5 564 Jacinta Telen Penaching Village Chandel ST enclosed required documents Experience Mayanglangjing Tamang Imphal Applicant to submit the 6 756 -

Perception of Non-Phonological Reduction: a Case Study for Using Experimental Data to Investigate Rule-Based Phonology and Exemplar Theory

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 7-2012 Perception of Non-Phonological Reduction: A Case Study for Using Experimental Data to Investigate Rule-Based Phonology and Exemplar Theory Rachael Tatman College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Tatman, Rachael, "Perception of Non-Phonological Reduction: A Case Study for Using Experimental Data to Investigate Rule-Based Phonology and Exemplar Theory" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 492. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/492 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Perception of Non-Phonological Reduction: A Case Study for Using Experimental Data to Investigate Rule-Based Phonology and Exemplar Theory Rachael Tatman May 9, 2012 Contents 1 Introduction and Background 3 1.1 Rule-Based Phonology . 5 1.2 Exemplar Theory . 6 1.3 Coronal Stop to Flap Reduction in American English . 6 2 Experiment 1 9 2.1 Methodology . 10 2.1.1 Items . 10 2.1.2 Procedure . 13 2.1.2.1 Participants . 14 2.2 Results . 15 2.3 Discussion . 15 3 Experiment 2 18 3.1 Methodology . 18 3.1.1 Items and Procedure . 18 3.1.2 Participants . 19 3.2 Results . 19 3.3 Discussion . 20 3.4 Discussion of Experiments 1 and 2 . -

FINAL OBSTRUENT VOICING in LAKOTA: PHONETIC EVIDENCE and PHONOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS Juliette Blevins Ander Egurtzegi Jan Ullrich

FINAL OBSTRUENT VOICING IN LAKOTA: PHONETIC EVIDENCE AND PHONOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS Juliette Blevins Ander Egurtzegi Jan Ullrich The Graduate Center, Centre National de la Recherche The Language City University of New York Scientifique / IKER (UMR5478) Conservancy Final obstruent devoicing is common in the world’s languages and constitutes a clear case of parallel phonological evolution. Final obstruent voicing, in contrast, is claimed to be rare or non - existent. Two distinct theoretical approaches crystalize around obstruent voicing patterns. Tradi - tional markedness accounts view these sound patterns as consequences of universal markedness constraints prohibiting voicing, or favoring voicelessness, in final position, and predict that final obstruent voicing does not exist. In contrast, phonetic-historical accounts explain skewed patterns of voicing in terms of common phonetically based devoicing tendencies, allowing for rare cases of final obstruent voicing under special conditions. In this article, phonetic and phonological evi - dence is offered for final obstruent voicing in Lakota, an indigenous Siouan language of the Great Plains of North America. In Lakota, oral stops /p/, /t/, and /k/ are regularly pronounced as [b], [l], and [ɡ] in word- and syllable-final position when phrase-final devoicing and preobstruent devoic - ing do not occur.* Keywords : final voicing, final devoicing, markedness, Lakota, rare sound patterns, laboratory phonology 1. Final obstruent devoicing and final obstruent voicing in phonological theory . There is wide agreement among phonologists and phoneticians that many of the world’s languages show evidence of final obstruent devoicing (Iverson & Salmons 2011). Like many common sound patterns, final obstruent devoicing has two basic in - stantiations: an active form, involving alternations, and a passive form, involving static distributional constraints.