The Emergence of Dorsal Stops After High Vowels in Huishu∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

A RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R

A RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh James A. Miller Independent Scholar This paper presents a reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic, the putative ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages, a Tibeto-Burman subgroup. A reconstructed rhyme inventory for the proto-language is presented. Correspondence sets for each of the members of the inventory are then systematically presented, along with supporting cognate sets drawn from four Tangkhulic languages: Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, and Tusom. This paper also summarizes the major sound changes that relate Proto-Tangkhulic to the daughter languages on which the reconstruction is based. It is concluded that Proto-Tangkhulic was considerably more conservative than any of these languages. It preserved the Proto-Tibeto-Burman length distinction in certain contexts and reflexes of final *-l, even though these are not preserved as such in Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, or Tusom. Proto-Tangkhulic is argued to be a potentially useful source of evidence in the reconstruction of Proto-Tibeto- Burman. Tangkhulic, comparative reconstruction, rhymes, vowel length 1. INTRODUCTION The goal of this paper is to present a preliminary reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic (PT), the ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages of Manipur and contiguous parts of India and Burma. It will show that Proto- Tangkhulic was a relatively conservative daughter language of Proto-Tibeto- Burman, preserving final *-l, and the vowel length distinction (in some contexts), among other features. As such, we suggest that Proto-Tangkhulic has significant importance in understanding the history of Tibeto-Burman. 1.1. The Tangkhulic language family All Tangkhulic languages are spoken in a compact area centered around Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India. -

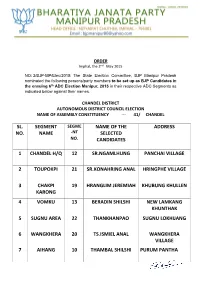

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

THE LANGUAGES of MANIPUR: a CASE STUDY of the KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE LANGUAGES OF MANIPUR: A CASE STUDY OF THE KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar Abstract: Manipur is primarily the home of various speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. Aside from the Tibeto-Burman speakers, there are substantial numbers of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers in different parts of the state who have come here either as traders or as workers. Keeping in view the lack of proper information on the languages of Manipur, this paper presents a brief outline of the languages spoken in the state of Manipur in general and Kuki-Chin languages in particular. The social relationships which different linguistic groups enter into with one another are often political in nature and are seldom based on genetic relationship. Thus, Manipur presents an intriguing area of research in that a researcher can end up making wrong conclusions about the relationships among the various linguistic groups, unless one thoroughly understands which groups of languages are genetically related and distinct from other social or political groupings. To dispel such misconstrued notions which can at times mislead researchers in the study of the languages, this paper provides an insight into the factors linguists must take into consideration before working in Manipur. The data on Kuki-Chin languages are primarily based on my own information as a resident of Churachandpur district, which is further supported by field work conducted in Churachandpur district during the period of 2003-2005 while I was working for the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, as a research investigator. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels 1. Introduction

The Emergence of Obstruents after High Vowels 1. Introduction Vennemann (1988) and others have argued that sound changes which insert segments most commonly do so in a manner that “improves” syllable structure: they provide syllables with onsets, allow consonants that would otherwise be codas to syllabify as onsets, relieve hiatus between vowels, and so on. On the other hand, the deletion of consonants seems to be particularly common in final position, a tendency that is reflected not only in the diachronic mechanisms outlined by Vennemann, but also reified in synchronic mechanisms like the Optimality Theoretic NoCoda constraint (Prince and Smolensky 1993). It may seem surprising, then, that there is small but robust class of sound changes in which obstruents (usually stops, but sometimes fricatives) emerge after word-final vowels. Discussions of individual instances of this phenomenon have periodically appeared in the literature. The best-known case is from Maru (a Tibeto-Burman language closely related to Burmese) and was discovered by Karlgren (1931), Benedict (1948), and Burling (1966; 1967). Ubels (1975) independently noticed epenthetic stops in Grassfields Bantu languages and Stallcup (1978) discussed this development in another Grassfields Bantu language, Moghamo, drawing an explicit parallel to Maru. Blust (1994) presented the most comprehensive treatment of these sound changes to date (in the context of making an argument about the unity of vowel and consonant features). To the Maru case, he added two additional instances from the Austronesian family: Lom (Belom) and Singhi. He also presented two historical scenarios through which these changes could occur: diphthongization and “direct hardening” of the terminus of the vowel. -

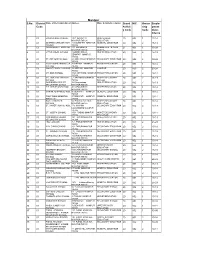

Manipur S.No

Manipur S.No. District Name of the Establishment Address Major Activity Description Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Activit ship yment y Code Code Class Interva l 101OKLONG HIGH SCHOOL 120/1 SENAPATI HIGH SCHOOL 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795104 EDUCATION 201BETHANY ENGLISH HIGH 149 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795104 301GOVERNMENT HOSPITAL 125 MAKHRALUI HUMAN HEALTH CARE 21 861 1 30-99 MANIPUR 795104 CENTRE 401LITTLE ANGEL SCHOOL 132 MAKHRELUI, HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 SENAPATI MANIPUR 795106 501ST. ANTHONY SCHOOL 28 MAKHRELUI MANIPUR SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 30-99 795106 601TUSII NGAINI KHUMAI UJB 30 MEITHAI MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 1 10-14 SCHOOL 795106 701MOUNT PISGAH COLLEGE 14 MEITHAI MANIPUR COLLEGE 20 853 2 20-24 795106 801MT. ZION SCHOOL 47(2) KATHIKHO MANIPUR PRIMARY EDUCATION 20 851 2 10-14 795106 901MT. ZION ENGLISH HIGH 52 KATHIKHO MANIPUR HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 15-19 SCHOOL 795106 SCHOOL 10 01 DON BOSCO HIGHER 38 Chingmeirong HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 7 15-19 SECONDARY SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 11 01 P.P. CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 40 LAIROUCHING HIGHER EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 MANIPUR 795105 12 01 MARAM ASHRAM SCHOOL 86 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 852 1 10-14 795105 13 01 RANGTAIBA MEMORIAL 97 SENAPATI MANIPUR GENERAL EDUCATION 20 853 1 10-14 INSTITUTE 795105 14 01 SAINT VINCENT'S 94 PUNGDUNGLUNG HIGHER SECONDARY 20 852 2 10-14 SCHOOL MANIPUR 795105 EDUCATION 15 01 ST. XAVIER HIGH SCHOOL 179 MAKHAN SECONDARY EDUCATION 20 852 2 15-19 LOVADZINHO MANIPUR 795105 16 01 ST. -

Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District 2014

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 2014 DISTRICT STATISTICAL OFFICE, UKHRUL DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR PREFACE The present issue of ‘Statistical Year Book of Ukhrul District, 2014’ is the 8th series of the publication earlier entitled „Statistical Abstract of Ukhrul District, 2007‟. It presents the latest available numerical information pertaining to various socio-economic aspects of Ukhrul District. Most of the data presented in this issue are collected from various Government Department/ Offices/Local bodies. The generous co-operation extended by different Departments/Offices/ Statutory bodies in furnishing the required data is gratefully acknowledged. The sincere efforts put in by Shri N. Hongva Shimray, District Statistical Officer and staffs who are directly and indirectly responsible in bringing out the publications are also acknowledged. Suggestions for improvement in the quality and coverage in its future issues of the publication are most welcome. Dated, Imphal Peijonna Kamei The 4th June, 2015 Director of Economics & Statistics Manipur. C O N T E N T S Table Page Item No. No. 1. GENERAL PARTICULARS OF UKHRUL DISTRICT 1 2. AREA AND POPULATION 2.1 Area and Density of Population of Manipur by Districts, 2011 Census. 1 2.2 Population of Manipur by Sector, Sex and Districts according to 2011 2 Census 2.3 District wise Sex Ratio of Manipur according to Population Censuses 2 2.4 Sub-Division-wise Population and Decadal Growth rate of Ukhrul 3 District 2.5 Population of Ukhrul District by Sex 3 2.6 Sub-Division-wise Population in the age group 0-6 of Ukhrul District by sex according to 2011 census 4 2.7 Number of Literates and Literacy Rate by Sex in Ukhrul District 4 2.8 Workers and Non-workers of Ukhrul District by sex, 2001 and 2011 5 censuses 3. -

The Village Community Among the Tangkhul Nagas of Manipur in the Nineteenth Century

================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 15:2 February 2015 ================================================================== The Village Community among the Tangkhul Nagas of Manipur in the Nineteenth Century Console Zamreinao Shimrei, M.Phil., NET., Ph.D. Research Scholar =============================================== Abstract The Tangkhuls occupy the north eastern hill of Ukhrul District, Manipur. Tangkhul people know no other life except that of “community life”. In fact, they work in groups, eat in groups, work in groups and sleep in groups wherever there are. All things are done in groups and in the full presence of the entire community. The individuals have no existence apart from the community. Interestingly, there was no place for idle men in the Tangkhul Naga community. The principle “He who does not work, neither shall he eat” is adopted by the Tangkhul Nagas. All must work and participate in the community work - may it be house building, feasts of merit or harvesting, everyone must join the community work. In the nineteenth century, the farmers of the village community were very helpful in time of happiness and sorrow. There was no hierarchical system in the social set up. Collection of wooden materials and construction of house took only a few days. There was a strong sense of corporate responsibility present in the construction of any house including the chief’s house in the village which is an indivisible unit. The sense of collective accountability has been responsible for the integrity of the community. In the village community ‘Longshim’ or dormitory played the most vital important role in shaping young men’s and women’s life. -

UC Berkeley Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society

UC Berkeley Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society Title Lexical Prefixes and Tibeto-Burman Laryngeal Contrasts Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1229x8bj Journal Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 37(37) ISSN 2377-1666 Author Mortensen, David R Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Lexical prefixes and Tibeto-Burman laryngeal contrasts Author(s): David R. Mortensen Proceedings of the 37th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2013), pp. 272-286 Editors: Chundra Cathcart, I-Hsuan Chen, Greg Finley, Shinae Kang, Clare S. Sandy, and Elise Stickles Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/. The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage, the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. Lexical Prefixes and Tibeto-Burman Laryngeal Contrasts DAVID R. MORTENSEN University of Pittsburgh Introduction The correspondences between Tibeto-Burman onsets are complex and often diffi- cult to explain as products of regular, phonetically conditioned sound change. This is particularly true with regard to their laryngeal features. In his ground-breaking reconstruction of Proto-Tibeto-Burman (PTB), Benedict (1972:17–18) provides the following set of reflexes for his reconstructed PTB stops: PTB Tibetan Jingpho Burmese Garo Mizo *p ph pph p bph pph p bph b ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ *t th tth t dth tth t dth t tsh ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ *k kh kkh k gkh kkh k gkh k ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ *b b b p ph pbp ph b ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ *d d d t th tdt th d ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ *g g g k kh kgk kh k ∼ ∼ ∼ ∼ Benedict reconstructs only two series of stops, despite the fact that there are a far larger number of consonant correspondences. -

Comparative Tangkhul∗

Comparative Tangkhul∗ David Mortensen University of California, Berkeley [email protected] December 17, 2003 Abstract This paper presents a preliminary lexical/phonological reconstruction of Proto-Tangkhul (PTk) and presents a tentative but general overview of the sound changes that relate this meso- language to Proto-Tibeto-Burman (PTB)—as reconstructed by Matisoff (2003)—and to three daughter languages (Standard Tangkhul, Kachai, and Huishu). The phonological correspon- dences and reconstructions are presented according to prosodic constituents (prefixes, onsets, rhymes, and tones). These subsections include discussions of several theoretically interesting sound changes and morphological developments. 1 Introduction The name Tangkhul (also Luhuppa or Luppa, espcially in older literature) refers to an ethnic group of Manipur State, India, and contiguous parts of Nagaland (another state of India) and Burma (see Figure 1). The Tangkhuls are quite diversified linguistically, and the speech varieties of most Tangkhul villages are not mutually intelligible with those of neighboring villages (though the sim- ilarities are large enough to facilitate the rapid learning of one another’s languages). However, it is clear that the Tangkhul languages are closely related to one-another and form a distinct subgroup within the Tibeto-Burman family. It has long been noted that Tangkhul is a group of languages, rather than a single language (Brown 1837), however, almost all of the available descriptions of ∗This paper has profited immensely from -

The Tangkhulic Tongues Background How I Started Working on Endangered Languages Tangkhul Field Methods

Tangkhulic Tongues David R. Mortensen Introduction My The Tangkhulic Tongues Background How I Started Working on Endangered Languages Tangkhul Field Methods Encountering Kachai David R. Mortensen Working on Huishu A Second Couple East Tusom September 18, 2014 Sorbung Lessons Learned Tangkhulic Tongues David R. Mortensen Introduction My Background Tangkhul Field Methods Encountering Kachai Working on Huishu A Second Couple East Tusom Sorbung Lessons Learned Overview Tangkhulic Tongues David R. Mortensen A bit about my early background, with relation to Introduction documentation of endangered languages. My Background How I happened on to documenting an endangered Tangkhul language (Kachai). Field Methods Encountering How this led to work on another, much more Kachai endangered, language (Huishu). Working on Huishu How that led to more extensive work on two other A Second endangered languages, both of which were previously Couple East Tusom undescribed (East Tusom and Sorbung). Sorbung Lessons The morals of this story. Learned Theoretical and Area Interests Tangkhulic Tongues David R. Mortensen Areal interest in Southeast Asia. Introduction Previously carried out work on “Sinospheric” My Background languages, especially Hmong. Tangkhul Prior to Tangkhulic, did a very small amount of work Field Methods on a more “Indospheric” language, Hakha Lai. Encountering Kachai Theoretical interests: Working on Huishu Phonology Morphology A Second Couple Historical linguistics/language change East Tusom Sorbung Typology Lessons Learned Previous Work on Minority Languages Tangkhulic Tongues David R. Mortensen Introduction My main language, prior to my work on Tangkhulic, My was Hmong. Background A minority language of China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand Tangkhul Field Methods (and also the US, Australia, France, French Guiana, etc.) Encountering Threatened in some countries, but not endangered.