Comparative Tangkhul∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

A RECONSTRUCTION of PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R

A RECONSTRUCTION OF PROTO-TANGKHULIC RHYMES David R. Mortensen University of Pittsburgh James A. Miller Independent Scholar This paper presents a reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic, the putative ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages, a Tibeto-Burman subgroup. A reconstructed rhyme inventory for the proto-language is presented. Correspondence sets for each of the members of the inventory are then systematically presented, along with supporting cognate sets drawn from four Tangkhulic languages: Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, and Tusom. This paper also summarizes the major sound changes that relate Proto-Tangkhulic to the daughter languages on which the reconstruction is based. It is concluded that Proto-Tangkhulic was considerably more conservative than any of these languages. It preserved the Proto-Tibeto-Burman length distinction in certain contexts and reflexes of final *-l, even though these are not preserved as such in Ukhrul, Huishu, Kachai, or Tusom. Proto-Tangkhulic is argued to be a potentially useful source of evidence in the reconstruction of Proto-Tibeto- Burman. Tangkhulic, comparative reconstruction, rhymes, vowel length 1. INTRODUCTION The goal of this paper is to present a preliminary reconstruction of the rhyme system of Proto-Tangkhulic (PT), the ancestor of the Tangkhulic languages of Manipur and contiguous parts of India and Burma. It will show that Proto- Tangkhulic was a relatively conservative daughter language of Proto-Tibeto- Burman, preserving final *-l, and the vowel length distinction (in some contexts), among other features. As such, we suggest that Proto-Tangkhulic has significant importance in understanding the history of Tibeto-Burman. 1.1. The Tangkhulic language family All Tangkhulic languages are spoken in a compact area centered around Ukhrul District, Manipur State, India. -

Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 10 : 12 December 2010 ISSN 1930-2940

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 10 : 12 December 2010 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. K. Karunakaran, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. Contents List Colloquial versus Standard in Singaporean Language Policies ... Tania Rahman, M.A. 1-27 Listening, an Art? ... Arun K. Behera, M.A., PGDTE, DDE, PGDJ, AMSPI, Ph.D., PDF 28-32 Bilingual Persons with Mild Dementia - Spectrum of Cognitive Linguistic Functions ... Deepa M.S., Ph.D. Candidate and Shyamala K. Chengappa, Ph.D. 33-48 How does Washback Work on the EFL Syllabus and Curriculum? - A Case Study at the HSC Level in Bangladesh ... M. Maniruzzaman, M.A., M. Phil., Ph.D. and M. Enamul Hoque, M.A., M. Phil., Ph.D. 49-88 Impact of Participative Management on Employee Job Satisfaction and Performance in Pakistan ... Saeed ul Hassan Chishti, Ph.D., Maryam Rafiq, M.B.A., Fazalur Rahman, M.Phil., M.Sc., M.Ed., Nabi Bux Jumani, Ph.D. and Muhammad Ajmal, Ph.D. 89-101 Homeless in One's Own Home - An Analysis of Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things and Lakshmi Kannan's Going Home ... Pauline Das, Ph.D. 102-106 Formative Influences on Sir Salman Rushdie ... Prabha Parmar, Ph.D. 107-116 Role of Science Education Projects for the Qualitative Improvement of Science Teachers at the Secondary Level in Pakistan .. -

A Print Version of All the Papers Of

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 15:2 February 2015 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. C. Subburaman, Ph.D. (Economics) N. Nadaraja Pillai, Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Materials published in Language in India www.languageinindia.com are indexed in EBSCOHost database, MLA International Bibliography and the Directory of Periodicals, ProQuest (Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts) and Gale Research. The journal is listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals. It is included in the Cabell’s Directory, a leading directory in the USA. Articles published in Language in India are peer-reviewed by one or more members of the Board of Editors or an outside scholar who is a specialist in the related field. Since the dissertations are already reviewed by the University-appointed examiners, dissertations accepted for publication in Language in India are not reviewed again. This is our 15th year of publication. All back issues of the journal are accessible through this link: http://languageinindia.com/backissues/2001.html Contents RIP RP: In Search of a More Pragmatic Model for Pronunciation Teaching in the Indian Context ... Anindya Syam Choudhury, Ph.D., PGCTE, PGDTE, CertTESOL (Trinity, London) 1-11 Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 15:2 February 2015 List of Contents i Enhancement of Public Speaking Skill through Practice among Teacher-Trainees in English: A Study .. -

CDC) Dataset Codebook

The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset Codebook (Version 1.0, 2015.07) (Presented in Bartusevičius, Henrikas (2015) Introducing the Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) dataset. Forthcoming in Conflict Management and Peace Science) The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset provides a categorization of 331 intrastate armed conflicts recorded between 1946 and 2010 into four categories: 1. Ethnic governmental; 2. Ethnic territorial; 3. Non-ethnic governmental; 4. Non-ethnic territorial. The dataset uses the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset v.4-2011, 1946 – 2010 (Themnér & Wallensteen, 2011; also Gleditsch et al., 2002) as a base (and thus is an extension of the UCDP/PRIO dataset). Therefore, the dataset employs the UCDP/PRIO’s operational definition of an aggregate armed conflict: a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths (Themnér, 2011: 1). The dataset contains only internal and internationalized internal armed conflicts listed in the UCDP/PRIO dataset. Internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) without intervention from other states’ (ibid.: 9). Internationalized internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) with intervention from other states (secondary parties) on one or both sides’(ibid.). For full definitions and further details please consult the 1 codebook of the UCDP/PRIO dataset (ibid.) and the website of the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University: http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/. -

Three Language Formula and the First and Second Language: a Case of North East India

================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 17:8 August 2017 UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ================================================================ Three Language Formula and the First and Second Language: A Case of North East India Ch. Sarajubala Devi ======================================================= Abstract Today, the role to be played by school in the life of a child is crucial. It is because in the name of right to education, a child has to learn almost all the skills and knowledge from school as he / she has to attain school at the earliest. Along with the recognition of education as the fundamental right of every child, providing access to educational facilities to every child from the age of 6 year to 14 years is an important task of every state. School should provide a space where children enjoy every right of learning that is ‘right to learn in one’s mother tongue’, ‘right to learn in one’s habitat’, ‘right to learn in one’s own culture’, etc. However, it is observed that schools in many cases became an isolated space where children always find a gap between what they do at home and what they are asked to do at school. One of the important reasons for this gap is that schools fail to recognize the habitat and languages specially that belong to the children of minority groups.1 To respond to the multilingual character India has adopted Three Language Formula (TLF), National Curriculum Framework 2005(NCF-05) suggests implementation of TLF in letter and spirit. TLF is implemented in North East India, but there is confusion in the designation of first language and the second language. -

'Collective Memory' As an Alternative to Dominant (Hi)Stories In

NATASA THOUDAM: ‘Collective Memory’ as an Alternative to Dominant (Hi)stories in Narratives by Women from and in Manipur Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. II, Issue 1 Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. II, Issue 1, (ISSN 2455-6564) Abstract Theorizing in the context of France, Pierre Nora laments the erosion of ‗national memory‘ or what he calls ―milieux de memoire‖ and the emergence of what have remained of such an erosion as ‗sites of memory‘ or ―lieux de memoire‖ (7–24). Further he contends that all historic sites or ―lieux d’histoire‖ (19) such as ―museums, archives, cemeteries, festivals, anniversaries, treaties, depositions, monuments, sanctuaries, fraternal orders‖ (10) and even the ―historian‖ can become lieux de memoire provided that in their invocation there is a will to remember (19). In contrast to Nora‘s lamentation, in the particular context of Manipur, a state in Northeast part of India, there is a reversal. It is these very ‗sites of memory‘ that bring to life the ‗collective memory‘ of Manipur, which is often national, against the homogenizing tendencies of the histories of conflicting nationalisms in Manipur, including those of the Indian nation-state. This paper shows how photographs of Manorama Thangjam‘s ‗raped‘ body, the suicide note of the ‗raped‘ Miss Rose, Mary Kom‘s autobiography, and ‗Rani‘ Gaidinlui‘s struggle become sites for ‗collective‘ memory that emerge as an alternative to history in Manipur. Keywords: Manipuri Women Writers, Pierre Nora, Conflict of Nationalisms, Collective Memory, Sites of Memory 34 Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. II, Issue 1, (ISSN 2455-6564) Theorizing in the context of France, Pierre Nora laments the erosion of ‗national memory‘ or what he calls ―milieux de memoire‖ and the emergence of what have remained of such an erosion as ‗sites of memory‘ or ―lieux de memoire‖ (7–24). -

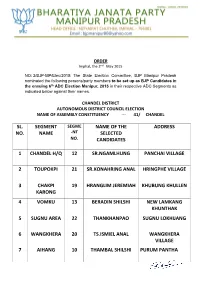

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

THE LANGUAGES of MANIPUR: a CASE STUDY of the KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE LANGUAGES OF MANIPUR: A CASE STUDY OF THE KUKI-CHIN LANGUAGES* Pauthang Haokip Department of Linguistics, Assam University, Silchar Abstract: Manipur is primarily the home of various speakers of Tibeto-Burman languages. Aside from the Tibeto-Burman speakers, there are substantial numbers of Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers in different parts of the state who have come here either as traders or as workers. Keeping in view the lack of proper information on the languages of Manipur, this paper presents a brief outline of the languages spoken in the state of Manipur in general and Kuki-Chin languages in particular. The social relationships which different linguistic groups enter into with one another are often political in nature and are seldom based on genetic relationship. Thus, Manipur presents an intriguing area of research in that a researcher can end up making wrong conclusions about the relationships among the various linguistic groups, unless one thoroughly understands which groups of languages are genetically related and distinct from other social or political groupings. To dispel such misconstrued notions which can at times mislead researchers in the study of the languages, this paper provides an insight into the factors linguists must take into consideration before working in Manipur. The data on Kuki-Chin languages are primarily based on my own information as a resident of Churachandpur district, which is further supported by field work conducted in Churachandpur district during the period of 2003-2005 while I was working for the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, as a research investigator. -

The Emergence of Obstruents After High Vowels 1. Introduction

The Emergence of Obstruents after High Vowels 1. Introduction Vennemann (1988) and others have argued that sound changes which insert segments most commonly do so in a manner that “improves” syllable structure: they provide syllables with onsets, allow consonants that would otherwise be codas to syllabify as onsets, relieve hiatus between vowels, and so on. On the other hand, the deletion of consonants seems to be particularly common in final position, a tendency that is reflected not only in the diachronic mechanisms outlined by Vennemann, but also reified in synchronic mechanisms like the Optimality Theoretic NoCoda constraint (Prince and Smolensky 1993). It may seem surprising, then, that there is small but robust class of sound changes in which obstruents (usually stops, but sometimes fricatives) emerge after word-final vowels. Discussions of individual instances of this phenomenon have periodically appeared in the literature. The best-known case is from Maru (a Tibeto-Burman language closely related to Burmese) and was discovered by Karlgren (1931), Benedict (1948), and Burling (1966; 1967). Ubels (1975) independently noticed epenthetic stops in Grassfields Bantu languages and Stallcup (1978) discussed this development in another Grassfields Bantu language, Moghamo, drawing an explicit parallel to Maru. Blust (1994) presented the most comprehensive treatment of these sound changes to date (in the context of making an argument about the unity of vowel and consonant features). To the Maru case, he added two additional instances from the Austronesian family: Lom (Belom) and Singhi. He also presented two historical scenarios through which these changes could occur: diphthongization and “direct hardening” of the terminus of the vowel. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general