A Print Version of All the Papers Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur

A STUDY ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATION OF TANGKHUL COMMUNITY IN UKHRUL DISTRICT, MANIPUR. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIAL WORK UNDER THE BOARD OF SOCIAL WORK STUDIES BY DEPEND KAZINGMEI PRN. 15514002238 UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF DR. G. R. RATHOD DIRECTOR, SOCIAL SCIENCE CENTRE, BVDU, PUNE SEPTEMBER 2019 DECLARATION I, DEPEND KAZINGMEI, declare that the Ph.D thesis entitled “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur.” is the original research work carried by me under the guidance of Dr. G.R. Rathod, Director of Social Science Centre, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Pune, for the award of Ph.D degree in Social Work of the Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. I hereby declare that the said research work has not submitted previously for the award of any Degree or Diploma in any other University or Examination body in India or abroad. Place: Pune Mr. Depend Kazingmei Date: Research Student i CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, “A Study on Human Rights Violation of Tangkhul Community in Ukhrul District, Manipur”, which is being submitted herewith for the award of the Degree of Ph.D in Social Work of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Mr. Depend Kazingmei under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title of this or any other University or examining body. -

Tangkhul Naga Folksong)

International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies (IJIRAS) ISSN: 2394-4404 Volume 3 Issue 8, July 2016 A Study On The Love Themes In Hao Laa (Tangkhul Naga Folksong) R. K. Pamri Department of Cultural and Creative Studies, North Eastern Hill University (NEHU), Shillong, Meghalaya, India Abstract: Tangkhul is one of the Naga tribes residing in Ukhrul District of Manipur, in the North-Eastern part of India. Like any other tribe, the Tangkhuls have their own culture and traditions which set them apart from other neighbouring tribes. Their rich cultural heritage is narrated through folklore. One in particular is the Tangkhul folksong which has become a fundamental source of the history of the Tangkhuls since they had no tradition of written documentation from their early days. Communications in the form of songs, words, gestures and the like remain the bearer of their culture and customs for the continuing generations. In this paper some of the Hao laa in context to the theme of ‘love’ are studied and analyzed to bring out certain social significance. I. INTRODUCTION which now lie in the south-eastern part of the Xinjiang province.2 Music and song play a significant role in the different stages of human life starting from childhood to adolescence till death and these evolve around the different activities of human life. We find that lullabies are sung to pacify babies, game songs are found to have sung both by children as well as adults depending on the context of the game and many others. Again, elaborate songs are sung by the adults describing the ups and downs of life. -

Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 10 : 12 December 2010 ISSN 1930-2940

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 10 : 12 December 2010 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. K. Karunakaran, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. Contents List Colloquial versus Standard in Singaporean Language Policies ... Tania Rahman, M.A. 1-27 Listening, an Art? ... Arun K. Behera, M.A., PGDTE, DDE, PGDJ, AMSPI, Ph.D., PDF 28-32 Bilingual Persons with Mild Dementia - Spectrum of Cognitive Linguistic Functions ... Deepa M.S., Ph.D. Candidate and Shyamala K. Chengappa, Ph.D. 33-48 How does Washback Work on the EFL Syllabus and Curriculum? - A Case Study at the HSC Level in Bangladesh ... M. Maniruzzaman, M.A., M. Phil., Ph.D. and M. Enamul Hoque, M.A., M. Phil., Ph.D. 49-88 Impact of Participative Management on Employee Job Satisfaction and Performance in Pakistan ... Saeed ul Hassan Chishti, Ph.D., Maryam Rafiq, M.B.A., Fazalur Rahman, M.Phil., M.Sc., M.Ed., Nabi Bux Jumani, Ph.D. and Muhammad Ajmal, Ph.D. 89-101 Homeless in One's Own Home - An Analysis of Arundhati Roy's The God of Small Things and Lakshmi Kannan's Going Home ... Pauline Das, Ph.D. 102-106 Formative Influences on Sir Salman Rushdie ... Prabha Parmar, Ph.D. 107-116 Role of Science Education Projects for the Qualitative Improvement of Science Teachers at the Secondary Level in Pakistan .. -

Role of Traditional Homegardens in Biodiversity Conservation and Socioecological Significance in Tangkhul Community in Northeast India

Tropical Ecology 59(3): 533–539, 2018 ISSN 0564-3295 © International Society for Tropical Ecology www.tropecol.com Role of traditional homegardens in biodiversity conservation and socioecological significance in Tangkhul community in Northeast India TUISEM SHIMRAH1*, PEIMI LUNGLENG1, CHONSING SHIMRAH2, Y. S. C. KHUMAN3 & 4 FRANKY VARAH 1University School of Environment Management, GGSIP University, New Delhi 2Department of Anthropology, Delhi University, Delhi 3School of Inter-Disciplinary and Trans-Disciplinary Studies, Indira Gandhi National Open University, New Delhi. 4Department of Environmental Studies, Bhaskaracharya College of Applied Science, Delhi University, New Delhi Abstract: Traditional communities in various parts of the world are facing various challenges owing to shrinking per capita land availability and growing market economy. This has led to shift in land use in which polyculture of variety of traditional crops are being slowly replaced by market driven monoculture system of cultivation to meet the demands to market on one side and maximization of production on the other side. As a result, the traditional crops in homegarden are being threatened in many areas. A study on conservation of tradition crops in homegarden in Tangkhul community in Ukhrul District of Manipur, India was carried out to assess the impact of such change in terms of crop species and their socioecological significance. A total of 73 plant species of economic, social and cultural values belonging to 27 families were recorded in homegardens. Result of this study shows that Tangkhul traditional community has vast indigenous knowledge on conservation of biodiversity in limited homegarden sites. Understanding traditional knowledge concerning HGs and how this form the knowledge for choice of species across the local community could help developing better strategies for sustainable management of traditional homegarden. -

7112712551213Eokjhjustificati

Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre- Final Alignment construction services in respect of 2 laning of Pallel-Chandel Option Study Report Section of NH- 102C on Engineering, Procurement and Construction mode in the state of Manipur. ALIGNMENT OPTION STUDY 1.1 Prologue National Highways and Infrastructure Development Corporation (NHIDCL) is a fully owned company of the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRT&H), Government of India. The company promotes, surveys, establishes, design, build, operate, maintain and upgrade National Highways and Strategic Roads including interconnecting roads in parts of the country which share international boundaries with neighboring countrie. The regional connectivity so enhanced would promote cross border trade and commerce and help safeguard India’s international borders. This would lead to the formation of a more integrated and economically consolidated South and South East Asia. In addition, there would be overall economic benefits for the local population and help integrate the peripheral areas with the mainstream in a more robust manner. As a part of the above mentioned endeavor, National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) has been entrusted with the assignment of Consultancy Services for Carrying out Feasibility Study, Preparation of Detailed Project Report and providing pre-construction services in respect of 2 laning with paved of Pallel-Chandel Section of NH-102C in the state of Manipur. National Highways & Infrastructure Development Corporation Ltd. is the employer and executing agency for the consultancy services and the standards of output required from the appointed consultants are of international level both in terms of quality and adherence to the agreed time schedule. -

Women, Peace and Security"

In 2000 the UN Security Council adopted Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 on "Women, Peace and Security". It acknowledges the disproportionate effects of war and conflict on women, as well as the influence women can and must have in prevention and resolution of conflict, and in peace and reconstruction processes. Its main goals are to enhance women's role and decision-making capacities with regard to conflict prevention, conflict resolution and peace building; and to significantly improve factors that directly influence women's security. Finland launched its National Action Plan on the implementation of UNSCR 1325 in 2008. The main objective of this research is to contribute to the understanding of, and provide practical recommendations on, how the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland can: i) Implement Finland's National Action Plan on 1325 through development cooperation, especially its commitment to facilitate women's participation in decision-making in conflict situations, peace processes and post-conflict activities, as well as to protect women in conflicts; ii) Support conflict prevention and post conflict development by strengthening women's role, and empowering women in countries with fragile situations; and; iii) Monitor and measure the Security and Peace Women, progress of such implementation. In addition, the study explored three specific, innovative themes relevant for the question of Women, Peace and Security: i) Involvement of Men; ii) Internally Displaced Persons; and iii) Environment. This study was carried out from April to December 2009 and included case studies in Kenya, Nepal and North-Eastern India, all of which represent countries or areas in diverse and complex conflict and post-conflict situations. -

CDC) Dataset Codebook

The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset Codebook (Version 1.0, 2015.07) (Presented in Bartusevičius, Henrikas (2015) Introducing the Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) dataset. Forthcoming in Conflict Management and Peace Science) The Categorically Disaggregated Conflict (CDC) Dataset provides a categorization of 331 intrastate armed conflicts recorded between 1946 and 2010 into four categories: 1. Ethnic governmental; 2. Ethnic territorial; 3. Non-ethnic governmental; 4. Non-ethnic territorial. The dataset uses the UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset v.4-2011, 1946 – 2010 (Themnér & Wallensteen, 2011; also Gleditsch et al., 2002) as a base (and thus is an extension of the UCDP/PRIO dataset). Therefore, the dataset employs the UCDP/PRIO’s operational definition of an aggregate armed conflict: a contested incompatibility that concerns government and/or territory where the use of armed force between two parties, of which at least one is the government of a state, results in at least 25 battle-related deaths (Themnér, 2011: 1). The dataset contains only internal and internationalized internal armed conflicts listed in the UCDP/PRIO dataset. Internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) without intervention from other states’ (ibid.: 9). Internationalized internal armed conflict ‘occurs between the government of a state and one or more internal opposition group(s) with intervention from other states (secondary parties) on one or both sides’(ibid.). For full definitions and further details please consult the 1 codebook of the UCDP/PRIO dataset (ibid.) and the website of the Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University: http://www.pcr.uu.se/research/ucdp/definitions/. -

Manipur State Information Technology Society

MANIPUR STATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY SOCIETY (A Government of Manipur Undertaking) 4th Floor, Western Block, New Secretariat, Imphal – 795001 www.msits.gov.in; Email: [email protected] Phone: 0385-24476877 District wise Status of Common Service Centres (As on 25th March, 2013) District: Ukhrul Total No. of CSCs : 33 VSAT Solar Power Sl. CSC Location & VLE Contact District BLOCK CSC Name Name of VLE Installation pack status No Address Number Status 1 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Hundung Hundung K.Y.S Yangmi 9612005006 Installed Installed 2 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Kalhang Kalhang R.S. Michael (Aphung) 9612765614 / Pending Installed 9612130987 3 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Nungshong Nungshong Khullen Ignitius Yaoreiwung 9862883374 Pending Installed Khullen Chithang 4 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangkai Shangkai Chongam Haokip 9612696292 Installed Installed 5 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-New Cannon New Cannon ZS Somila 9862826487 / Installed Installed 9862979109 6 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Jessami Jessami Village Nipekhwe Lohe 9862835841 Pending Installed 7 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Teinem Teinem Mashangam Raleng 8730963043 Pending Installed 8 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Seikhor Seikhor L.A. Pamreiphi 9436243204 / Pending Installed 857855919 / 8731929981 9 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Chingjaroi Chingjaroi Khullen Joyson Tamang 9862992294 Pending Installed Khullen 10 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Litan Litan JS. Aring 9612937524 / Installed Installed 8974425854 / 9436042452 11 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangshak Shangshak khullen R.S. Ngaranmi 9862069769 / Pending Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9436086067 / 9862701697 12 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Lambui Lambui L. Seth 9612489203 / Installed Installed T.D.Block 8974459592 / 9862038398 13 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Kasom Kasom Khullen Shanglai Thangmeichui 9862760611 / Not approved for Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9612320431 VSAT 14 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Khamlang Khamlang N. -

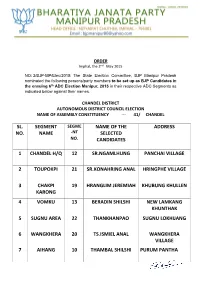

Sl. No. Segment Name Name of the Selected Candidates

ORDER Imphal, the 2nd May 2015 NO: 2/BJP-MP/Elec/2015: The State Election Committee, BJP Manipur Pradesh nominated the following persons/party members to be set up as BJP Candidates in the ensuing 6th ADC Election Manipur, 2015 in their respective ADC Segments as indicated below against their names. CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 41/ CHANDEL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 CHANDEL H/Q 12 SR.NGAMLHUNG PANCHAI VILLAGE 2 TOUPOKPI 21 SR.KONAHRING ANAL HRINGPHE VILLAGE 3 CHAKPI 19 HRANGLIM JEREMIAH KHUBUNG KHULLEN KARONG 4 VOMKU 13 BERADIN SHILSHI NEW LAMKANG KHUNTHAK 5 SUGNU AREA 22 THANKHANPAO SUGNU LOKHIJANG 6 WANGKHERA 20 TS.ISMIEL ANAL WANGKHERA VILLAGE 7 AIHANG 10 THAMBAL SHILSHI PURUM PANTHA 8 PANTHA 11 H.ANGTIN MONSANG JAPHOU VILLAGE 9 SAJIK TAMPAK 23 THANGSUANKAP GELNGAI VILAAGE 10 TOLBUNG 24 THANGKHOMANG AIBOL JOUPI VILLAGE HAOKIP CHANDEL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 42/ TENGNOUPAL SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 KOMLATHABI 8 NG.KOSHING MAYON KOMLATHABI VILLAGE 2 MACHI 2 SK.KOTHIL MACHI VILLAGE, MACHI BLOCK 3 RILRAM 5 K.PRAKASH LANGKHONGCHING VILLAGE 4 MOREH 17 LAMTHANG HAOKIP UKHRUL DISTRICT AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT COUNCIL ELECTION NAME OF ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCY --- 43/ PHUNGYAR SL. SEGMENT SEGME NAME OF THE ADDRESS NO. NAME -NT SELECTED NO. CANDIDATES 1 GRIHANG 19 SAUL DUIDAND GRIHANG VILLAGE KAMJONG 2 SHINGKAP 21 HENRY W. KEISHING TANGKHUL HUNDUNG 3 KAMJONG 18 C.HOPINGSON KAMJONG BUNGPA KHULLEN 4 CHAITRIC 17 KS.GRACESON SOMI PUSHING VILLAGE 5 PHUNGYAR 20 A. -

The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy

THE IMPACT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE ON TANGKHUL LITERACY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH, PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) IN ENGLISH BY ROBERT SHIMRAY UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr. GAUTAMI PAWAR UNDER THE BOARD OF ARTS & FINEARTS STUDIES MARCH, 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” completed by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Robert Shimray Date: (Research Student) I CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “The Impact of English Language on Tangkhul Literacy” which is being submitted herewith for the award of the degree of Vidyavachaspati (Ph.D.) in English of Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune is the result of original research work completed by Robert Shimray under my supervision and guidance. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work incorporated in this thesis has not formed the basis for the award of any Degree or similar title or any University or examining body upon him. Place: Dr. Gautami Pawar Date: (Research Guide) II ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, having answered my prayer, I would like to thank the Almighty God for the privilege and opportunity of enlightening me to do this research work to its completion and accomplishment. Having chosen Rev. William Pettigrew to be His vessel as an ambassador to foreign land, especially to the Tangkhul Naga community, bringing the enlightenment of the ever lasting gospel of love and salvation to mankind, today, though he no longer dwells amongst us, yet his true immortal spirit of love and sacrifice linger. -

MANIPUR LIST of INSTITUTION for the YEAR 1983-84-D01266.Pdf

LIST OF INSTITUTIONS FOR THE YEAR 1983-84 ( GENERAL EDUCATION ) IN M AN IPUR A S O N 31 - 3-84 1983-84 COMPILED BY ; - PLANNING & STATISTICS UNIT. EDUCATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNiVIENr OF MANIPUR. LIST OF IMSTITLITlOiMS FQR THE YEAR 1963-64 (g e n e r a l EDUCTION IN nfiNIPUR) AS ON 31-3-84 CONTENTS S.l .NJvlcoc Particulars Page 1# . Iri'stitutiona relating to CollQgBS, Higher Secandary & High Schools. ............ 1-14 ?m Tnfltiiutiona relating to Junior High Schools ............15 - 3D 3, Primary Schools in Imphal District Zono-I .............. 13 4, Primary Schools in Imphal District Zone-II 11 5, . Primary Schools in Imphal District, Jilptbam............ ? fi. Primary Schncils in Thoubal District •••••.»*•• 11 7* Primary Schools in BiBhenpur District a« Primary Schuola in Ukhrul District .••••• .......... 9t Primary Schools in Senapati District , * • , ............ [0, Primary Snhnola in Tamenqlonc^ Dintrict 11* Primary Snhnnls in Churnchansipur District , , , 12. Primary Schools in Chandel District ...•«• NIEPA DC t il 111!^ D01266 ^1(7 J ‘ jrif ■ t S>'8U?it» ; U l ^ N..tic'i 1 iiuu.vue of Educalionil Planning and A*iinistrati<m 0 >B^iiA^bmdc Marg,NewDeIlu*>ll(XXII B0CNjw4Xi?.fo..., ....... ... B«*. ...........................^ .4 -?.//.?|... DI'nr:c~‘ i ;.v2^iAp^|yrr^!T-l•}T5L Of COi.LcIGES, -HIGHER SECC nrp-y YEAR 1 non-84 Dislrict/ Ool I on ti Total ^ □ H Q ^_____ L _______________________________________________________ _ __ ,_T_Dt a_l_ (_ £o_u J* ^i^ejd |_ lin-ad d_ed I Tn_ta2_ ______' ____1______ 1 2_ t J - - ^ - L -7- J -L « L 10- 11_I -12 I L -"1 - _ Jj^I - 1, Imphal Dist. -

ORDERS Imphal, the A' April, 2018

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION (S) (Administrative Section) ORDERS Imphal, the 17 'April, 2018 No.AO/59/1T(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/20 1 1(4)-DE(S): In supersession of all previous orders issued in this regard, services of the following 95(Ninety-five), Graduate teachers(RMSA) , Upper Primary Teachers(SSA) and Primary Teachers(SSA) are hereby utilised at the school shown against their name with immediate effect in public interest. 2. Consequent upon their utilisation they are hereby released from their present place of posting so as to enable them to join at the new place of utilisation immediately. 3. The Head of Institution concerned should submit a compliance report to the undersigned under intimation to the ZEO concerned. (Th. Kirankumar) Director of Education (S), MaIp1 ' Copy to: 1. PPS to Hon'ble Minister of Education, Manipur. 2. Principal Secretary/Education (S), Government of Manipur. 3. Additional Directors (H/V/PIg.), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 4. Sr. Finance Officer, Edn(S), Manipur 5. Nodal Officer (CPIS), Directorate of Education (S), Manipur. 6. ZEO concerned. 7. Head of the Institutions concerned. 8. Teacher concerned. 9. Relevant file. Annexure to Order No. AO/59/TT/(UTZ/RMSA/SSA)/2011(4)-DE(S) dated 13 Ir April, 2018 EIN Name of the Employee Designation Present Place of Posting Place of Utilisation 1 081054 Premjit Ningthoujam AGT(RMSA) Thamchet H/s CC Hr. Sec. School Chandrakhong Phanjakhong High 2 085756 Keisham Anupama Devi AGT(RMSA) Urup H/S School 3 098662 Konthoujam Sujeta Devi AGT(RMSA) Kasom Khullen H/S Azad Hr.