Practical Experiments in School Science Lessons and Science Field Trips: 19 July 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starting Secondary School September 2010

Starting Secondary School September 2010 Important dates to remember September/October 2009 School open evenings 23 October 2009* Closing date for applications 1 March 2010 Offers sent to parents 201015 March 2010 Acceptance deadline * If your child attends a Hillingdon primary school, you should return the paper application form to the Hillingdon primary school by noon on 21 October 2009. If you apply on-line this must be submitted by midnight on 23 October 2009. www.hillingdon.gov.uk 10091 Starting Secondary School 2010 brochure.indd 1 6/12/10 09:47:18 You can apply for a school place If you apply online, please DO NOT complete this online at www.eadmissions.org.uk paper application form Some of the benefits of applying for your child’s secondary school place online for September 2010 are: • you will receive confirmation that we have received your application if you supply an email address • you can view your application at any time during the admission process • you can change the details of your application i.e. which schools you name, right up to midnight on 23 October 2009 • you can find out which school your child has been offered from 7.00am on 2 March 2010 and you will receive an email confirming the offer later that day. The offer letters will be posted on 1 March 2010 and not received until 2 March at the earliest. • you can accept your offer online and you will have the choice to attach your proof of address documentation. There were 753 applications made online for September 2009, which is 23.8% of the total applications received. -

2009 Admissions Cycle

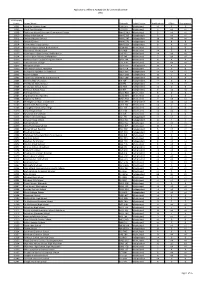

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2009 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10001 Ysgol Syr Thomas Jones LL68 9TH Maintained <4 0 0 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <4 <4 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 5 <4 <4 10010 Bedford High School MK40 2BS Independent 7 <4 <4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 18 <4 <4 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 20 8 8 10014 Dame Alice Harpur School MK42 0BX Independent 8 4 <4 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 5 0 0 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <4 0 0 10022 Queensbury Upper School, Bedfordshire LU6 3BU Maintained <4 <4 <4 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 7 <4 <4 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 8 4 4 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 12 <4 <4 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 15 4 4 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <4 0 0 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 15 7 6 10033 The School of St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 22 9 9 10035 Dean College of London N7 7QP Independent <4 0 0 10036 The Marist Senior School SL57PS Independent <4 <4 <4 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <4 0 0 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 <4 <4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 8 0 0 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained -

Starting Secondary School in Hillingdon > >

Starting Secondary School in Hillingdon > > Contents Pan-London Co-ordinated Admissions Scheme 3 Information on Admissions Criteria 5 How to apply 6 Applying for a school place on-line 11 Assistance for Children who live in Hillingdon 13 Secondary Schools in Hillingdon 14 Questionnaire 35 Other useful contacts 37 > Further information Further information and advice is available during normal offi ce hours on 01895 556644 www.hillingdon.gov.uk admissionsbenefi [email protected] > School Terms and Holdays 2007/08 Bank Holidays 2007/2008 Good Friday 21 March 2008 Easter Monday 24 March 2008 May Day 5 May 2008 Spring Bank Holiday 26 May 2008 Autumn Term 2007 74 Days Term Starts Monday 3 September 2007* Half Term Holiday 22 – 26 October 2007 Term Ends Thursday 20 December 2007 Spring Term 2008 58 Days Term Starts Monday 7 January 2008 Half Term Holiday 18 – 22 February 2008 Term Ends Friday 4 April 2008 Summer Term 2008 62 Days Term Starts Monday 21 April 2008 Half Term Holiday 26 – 30 May 2008 Term Ends Wednesday 23 July 2008 Total 194 Days *Note: Monday 3 September 2007 – INSET Day; 3 further training days to be determined by schools within the dates established The term dates for some Voluntary and Foundation schools may vary slightly from those shown above. Pan-London Co-ordinated Admissions Scheme> Every year around 60,000 pupils living in London transfer to secondary school, many crossing borough boundaries to do so. In 2005 all 33 London Boroughs together with some councils bordering the capital signed up to a system to co-ordinate admissions to their secondary schools. -

Grand Final 2020

GRAND FINAL 2020 Delivered by In partnership with grandfinal.online 1 WELCOME It has been an extraordinary year for everyone. The way that we live, work and learn has changed completely and many of us have faced new challenges – including the young people that are speaking tonight. They have each taken part in Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! – a programme which reaches over 20,000 young people a year. They have had a full day of training in communica�on skills and public speaking and have gone on to win either a Regional Final or Digital Final and earn their place here tonight. Every speaker has an important and inspiring message to share with us, and we are delighted to be able to host them at this virtual event. A message from A message from Sir Jack Petchey CBE Fiona Wilkinson Founder Patron Chair The Jack Petchey Founda�on Speakers Trust Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! At Speakers Trust we believe that helps young people find their voice speaking up is the first step to and gives them the skills and changing the world. Each of the young confidence to make a real difference people speaking tonight has an in the world. I feel inspired by each and every one of them. important message to share with us. Jack Petchey’s “Speak Public speaking is a skill you can use anywhere, whether in a Out” Challenge! has given them the ability and opportunity to classroom, an interview or in the workplace. I am so proud of share this message - and it has given us the opportunity to be all our finalists speaking tonight and of how far you have come. -

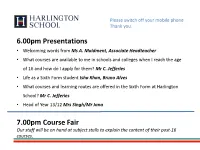

6.00Pm Presentations 7.00Pm Course Fair

Please switch off your mobile phone. Thank you. 6.00pm Presentations • Welcoming words from Ms A. Maidment, Associate Headteacher • What courses are available to me in schools and colleges when I reach the age of 16 and how do I apply for them? Mr C. Jefferies • Life as a Sixth Form student Isha Khan, Bruno Alves • What courses and learning routes are offered in the Sixth Form at Harlington School? Mr C. Jefferies • Head of Year 13/12 Mrs Singh/Mr Jana 7.00pm Course Fair Our staff will be on hand at subject stalls to explain the content of their post-16 courses. *Highly Stressful time *Big decisions to make *Do I... a) Remain at current school? b) Go to another school? c) Go to a college? d) Look for work-based training? Which courses? Choose a course/courses that: • Reflects your interests and personal qualities. • Enables you to learn in ways that best suit you. • You know you can do well in. • Will help you to move on whilst keeping your options open for the future. • Has entry requirements that you can achieve. Choose carefully, be realistic and remember that your choices will affect your future. What can I study? *Entry Level (no GCSE grades) *Level 1 courses (Generally for students with Grade 1/2) Foundation Level courses *Level 2 courses (Generally for students with Grades 2/3) Intermediate Level courses *Level 3 courses (Generally for students with 5+ Grades 4+) Advanced Level courses What can I study? *Level 1 courses (Generally for students with Grade 1/2): Foundation Level courses BTEC Award Cambridge Nationals NVQ Level 1 -

Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Progress Data As of 27 August 2020

Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data as of 27 August Ad-hoc notice – laptops, tablets and 4G wireless routers for disadvantaged and vulnerable children: by academy trust, and local authority. August 2020 Devices and 4G Wireless Routers Data Contents Introduction 3 Progress data 4 Definitions 8 Data Quality 9 Get technology support for disadvantaged and vulnerable children and young people during the coronavirus (COVID-19) Introduction Laptops and tablets have been provided for disadvantaged and vulnerable families, children and young people who did not have access to them through another source, to enable access to remote education and social care services during the coronavirus (COVID-19). Laptops, tablets and 4G wireless routers were given to local authorities (LAs) and academy trusts (trusts), who will own the devices and distribute them to families, children and young people. LAs and trusts could receive digital devices for: • care leavers • children and young people aged 0 to 19, or young children’s families, with a social worker • disadvantaged year 10 pupils Internet access was also provided through 4G wireless routers for any of the following people who did not have it: • care leavers • secondary school pupils with a social worker • disadvantaged year 10 pupils The Department for Education ordered over 200,000 laptops and tablets and over 50,000 4G wireless routers based on its estimate of the number of children and young people in the eligible categories set out above. LAs and trusts were invited to forecast the number of devices they needed to support children and young people, who they were responsible for, in the eligible categories. -

Grid Export Data

Organisation Name. First Name Last Name Email The de Ferrers Academy Steven Allen [email protected] Rockwood Academy Fuzel Choudhury [email protected] Nansen Primary School Catherine Rindl [email protected] Hunsley Primary School Lucy Hudson [email protected] Westwood College Andrew Shaw [email protected] St John's Marlborough Patrick Hazlewood [email protected] Devizes School Malcolm Irons [email protected] Hardenhuish School Jan Hatherell [email protected] Beacon Academy Anna Robinson [email protected] Blyth Academy Gareth Edmunds [email protected] Beauchamp College Kathryn Kelly [email protected] Wreake Valley Community College Tony Pinnock [email protected] Sir Robert Pattinson Academy Helen Renard [email protected] Chipping Norton School Simon Duffy [email protected] King Edward VII Science and Sport JenniferCollege Byrne [email protected] Rawlins Community College Mr Callum Orr [email protected] Charnwood College (Upper) Wendy Marshall [email protected] Newent Community School and SixthGlen Form Centre Balmer [email protected] Fairfield High School Catriona Mangham [email protected] The City Academy Bristol John Laycock [email protected] Unity City Academy Neil Powell [email protected] CTC Kingshurst Academy Damon Hewson [email protected] Sir John Gleed School Will Scott [email protected] -

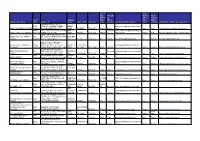

Grid Export Data

Accoun Chief ting Accounti Finance Chief Officer ng Officer Finance Trust Address First Officer First Officer Organisation Name. Type Address 1 Line 2 Town / City Postcode name Surname Accounting Officer Email Name Surname Chief Finance Officer Email Address BOURNE ABBEY C OF E Multi PRIMARY ACADEMY ABBEY ABBEY [email protected] ABBEY ACADEMIES TRUST Academy ROAD BOURNE PE10 9EP ROAD BOURNE PE10 9EP Sarah Moore ch.uk Jane King [email protected] Single ABBEY COLLEGE ABBEY ROAD ABBEY Christofor [email protected] ABBEY COLLEGE, RAMSEY Academy RAMSEY PE26 1DG ROAD RAMSEY PE26 1DG Andrew ou ambs.sch.uk Robert Heal [email protected] ABBEY GRANGE CHURCH OF ABBEY MULTI ACADEMY Multi ENGLAND ACADEMY BUTCHER BUTCHER TRUST Academy HILL LEEDS LS16 5EA HILL LEEDS LS16 5EA Ian Harmer [email protected] Ian Harmer [email protected] ABBOTS HALL PRIMARY ABBOTS HALL PRIMARY Single ACADEMY ABBOTTS DRIVE ABBOTTS STANFORD- [email protected] ACADEMY Academy STANFORD-LE-HOPE SS17 7BW DRIVE LE-HOPE SS17 7BW Laura Fishleigh k Joanne Forkner [email protected] RUSH COMMON SCHOOL ABINGDON LEARNING Multi HENDRED WAY ABINGDON, HENDRED Stevenso headteacher@rushcommonschool. TRUST Academy OXFORDSHIRE OX14 2AW WAY ABINGDON OX14 2AW Jacquie n org Zoe Bratt [email protected] Multi The Kingsway School Foxland Foxland ABNEY TRUST Academy Road Cheadle Cheshire SK8 4QX Road Cheshire SK8 4QX Jo Lowe [email protected] James Dunbar [email protected] -

Local Borough Schools List

Local Borough Schools List London Borough of Brent Alperton Community School Ark Academy (Secondary) Ark Elvin Academy Capital City Academy Claremont High School Convent of Jesus & Mary Language College Islamia Girls' Secondary School JFS Kingsbury High School Michaela Community School Newmam Catholic College Preston Manor School Queens Park Community School St Gregory’s Science College The Crest Academy Wembley High Technology College College of North West London - Wembley Centre College of North West London - Willesden Centre London Borough of Ealing Acton High School Alec Reed Academy Brentside High School Cardinal Wiseman Catholic School Dormers Wells High School Drayton Manor High School Ealing Fields High School (Sept 2015) Elthorne Park High School Featherstone High School Greenford High School Northolt High School The Ellen Wilkinson School for Girls Twyford High School Villiers High School William Perkin Church of England High School Ealing, Hammersmith & West London College - Acton Campus Ealing, Hammersmith & West London College - Ealing Campus Ealing, Hammersmith & West London College - Southall Campus London Borough of Hammersmith & Fulham Burlington Danes Academy Fulham College Fulham College Boys’ School Fulham Enterprise Studio The Fulham Boys School Hammersmith Academy Hurlingham and Chelsea School London Borough of Harrow Avanti House Bentley Wood High School Canons High School Harrow High School Hatch End High School Nower Hill High School Park High School Rooks Heath College for Business and Enterprise Salvatorian -

Person's Name

Ref: Starting Secondary 2020 September 2020 Dear Parent/Guardian TRANSFER TO SECONDARY SCHOOL – SEPTEMBER 2020 Your child is due to start secondary school in September 2020 and although your child attends a Hillingdon primary school you will need to submit your starting secondary school application to your home LA (Local Authority), this is who you pay your council tax to. You can still apply to any secondary schools in Hillingdon or outside of Hillingdon, but you must list these schools on your application to your home LA. Please visit www.eAdmissions.org.uk to submit an online application. Please be aware that the closing date for these applications is 31 October 2019. If you wish to look at a summary of the admissions criteria for all Hillingdon secondary schools, you can view the Hillingdon Secondary School Admissions brochure at www.hillingdon.gov.uk/schooladmissions. Yours sincerely School Placement and Admissions team Please turn over for Hillingdon open evening dates School Placement and Admissions Team Residents Services T.01895 556644 F.01895 277729 [email protected] www.hillingdon.gov.uk London Borough of Hillingdon, 4E/09, Civic Centre, High Street, Uxbridge, UB8 1UW Hillingdon Secondary Schools - open evening dates 2019 SCHOOL DATE TIME Barnhill Community School Wednesday 2 October 6.00pm Bishop Ramsey CofE School Tuesday 17 September 5.30pm Bishopshalt School Thursday 12 September 6.00pm Guru Nanak Sikh Academy Tuesday 8 October 5.00pm Harlington School Tuesday 1 October 6.00pm Haydon School Thursday 26 September -

Newsletter 111 Spring 2016

1 ABOVE - 1957 Entry Reunion Adrienne McCormick (Chalkley), Jacquie Enk (West), Gillian Baines (Winter), Pamela Hu- lett (Sims), Dave Durston (late Gay Perkins` husband), Julie Jenkinson (Terrill), Nick Ho- ten, Sue Crane (Symes), Carolyn Morton (Belsey), Graham Morton, Dave Scott, John Gibson, Sandra Gibson (Ross), Roger Vernon. Also present but not in the picture was Pat Dibben (Heard). Old Uxonians’ Association – Newsletter No. 111 – Spring 2016 NEWS FROM BISHOPSHALT The December stage production of "Cabaret" was an outstanding success. The challenging subject was covered extremely well, and the acting and dancing were of a very high standard. Everyone involved deserves congratulations. Tony Austin of NODA’s Show Report began: “After twenty years of attending the BODS pre-Christmas musicals at Bishopshalt and admiring the very special expertise put into each production by Staff and Pupils, there came something even more special on the Friday evening which I attended as your Reviewer together with the Head of NODA London keen to see what I have been raving about in my reports ……” JACQUELINE KIRKPATRICK (1991-1998), who joined the staff as an RE teacher in 2003, left in December to take up a post at Holmer Green Senior School in Bucks. In March a local resident came to the School reception desk with a copy of the 1932 long photograph. He had seen it in a used furniture store in Cowley, and bought it for the school. He has been recompensed for his generous gesture. KRP Young Chef 2016 In January, two students competed in the prestigious annual “Hillingdon Young Chef of the Year” competition at the Harefield Academy. -

Starting Secondary School 2005

Starting Secondary School 2004 How to apply for a place Copy of original 2 Starting Secondary School 2004 London Borough of Hillingdon OpenOpen eveningsevenings Each secondary school has an open evening during the Autumn Term for parents and pupils to visit the school. These evenings usually include a talk by the headteacher and a tour of the school. Often it will be possible to see current pupils at work and meet staff. We suggest you visit the secondary schools on their open evenings if you can: Date School Time Thursday 18 September Bishophalt School 7:30pm Thursday 25 September The Douay Martyrs School (Roman Catholic) 6:30pm Monday 29 September Uxbridge High School 6:30pm Tuesday 30 September Vyners School 6:30pm Tuesday 30 September Hayes Manor School 7:00pm Wednesday 1 October Abbotsfield School (boys) 6:30pm Thursday 2 October Swakeleys School (girls) 6:30pm Thursday 2 October Haydon School 7:00pm Tuesday 7 October Bishop Ramsey School (Church of England) 6:00pm Wednesday 8 October Northwood School 6:00pm Wednesday 8 October Barnhill School 6:30pm Thursday 9 October Queensmead School 6:00pm Thursday 9 October Mellow Lane School 6:30pm Tuesday 14 October Guru Nanak Sikh School 6:30pm Tuesday 14 October John Penrose School 7:00pm Wednesday 15 October Stockley Academy 7:00pm Thursday 16 October Harlington Community School 6:30pm IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO ATTEND AN OPEN EVENING, PLEASE CONTACT THE SCHOOL FOR ALTERNATIVE ARRANGEMENTS. IMPORTANT DATES TO REMEMBER September/October 2003 School open evenings 7th November 2003 Closing date