Rocks in the Whirlpool

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College and Research Libraries

ROBERT B. DOWNS The Role of the Academic Librarian, 1876-1976 . ,- ..0., IT IS DIFFICULT for university librarians they were members of the teaching fac in 1976, with their multi-million volume ulty. The ordinary practice was to list collections, staffs in the hundreds, bud librarians with registrars, museum cu gets in millions of dollars, and monu rators, and other miscellaneous officers. mental buildings, to conceive of the Combination appointments were com minuscule beginnings of academic li mon, e.g., the librarian of the Univer braries a centur-y ago. Only two univer sity of California was a professor of sity libraries in the nation, Harvard and English; at Princeton the librarian was Yale, held collections in ·excess of professor of Greek, and the assistant li 100,000 volumes, and no state university brarian was tutor in Greek; at Iowa possessed as many as 30,000 volumes. State University the librarian doubled As Edward Holley discovered in the as professor of Latin; and at the Uni preparation of the first article in the versity of · Minnesota the librarian present centennial series, professional li served also as president. brarHms to maintain, service, and devel Further examination of university op these extremely limited holdings catalogs for the last quarter of the nine were in similarly short supply.1 General teenth century, where no teaching duties ly, the library staff was a one-man opera were assigned to the librarian, indicates tion-often not even on a full-time ba that there was a feeling, at least in some sis. Faculty members assigned to super institutions, that head librarians ought vise the library were also expected to to be grouped with the faculty. -

Special Libraries, October 1964

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1964 Special Libraries, 1960s 10-1-1964 Special Libraries, October 1964 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1964 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, October 1964" (1964). Special Libraries, 1964. 8. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1964/8 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1964 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL LIBRARIES ASSOCIATION Putting Knowledge to Work OFFICERS DIRECTORS President WILLIAMK. BEATTY WILLIAMS. BUDINGTON Northwestern University Medic'il The John Crerar Library, Chicago, Illinois School, Chicago, Illinois President-Elect HELENEDECHIEF ALLEENTHOMPSON Canadian Nafional Railwa~r, General Electric Company, Sun Jose, California Montreal, Quebec Advisory Council Chairman JOAN M. HUTCHINSON(Secretary) Research Center, Diamond Alkali LORNAM. DANIELLS Company, Painesville, Ohio Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetl~ KENNETHN. METCALF Advisory Council Chairman-Elect Henry Ford Museum and Greei~. HERBERTS. WHITE field Village, Dearborn, Michigan NASA Facility, Documentation, Inc., Bethesda, Maryland MRS.ELIZABETH B. ROTH Treasurer Standard Oil Company of Cali- JEANE. FLEGAL fornia, San Francisco, California Union Carbide Corp., New YorR, New York MRS. DOROTHYB. SKAU Immediate Past-President Southern Regional Research Lab- MRS.MILDRED H. BRODE oratory, U.S. Department of Agri- David Taylor Model Basin, Washington, D. C. culture. New Orleans, Louirirrna EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: BILL M. -

2007–2008 Donor Roster

American Library Association 2007–2008 Donor Roster The American Library Association is a 501(c)(3) charitable and educational organization. ALA advocates funding and policies that support libraries as great democratic institutions, serving people of every age, income level, location, ethnicity, or physical ability, and providing the full range of information resources needed to live, learn, govern, and work. Through the generous support of our members and friends, ALA is able to carry out its work as the leading advocate for the public’s right to a free and open information society. We seek ongoing philanthropic support so that we continue to advocate on behalf of libraries and library users, provide scholarships to students preparing to enter the library profession, promote literacy and community outreach programs, and encourage reading and continuing education in communities across America. Contributions and tax-deductible bequests in any amount are invited. For more information, contact the ALA Development Office at 800.545.2433, or [email protected]. Marilyn Ackerman Jewel Armstrong Player Gary S. Beer Miriam A. Bolotin Heather J. Adair Mary J. Arnold Kathleen Behrendt Nancy M. Bolt Nancy L. Adam Judy Arteaga Penny M. Beile Ruth Bond Martha C. Adamson Joan L. Atkinson Steven J. Bell Lori Bonner Sharon K. Adley Sharilynn A. Aucoin Valerie P. Bell Roberta H. Borman Elizabeth Ahern Sahagian Rita Auerbach Robert J. Belvin Paula Bornstein Rosie L. Albritton Mary Augusta Thomas Betty W. Bender Eileen K. Bosch Linda H. Alexander Rolf S. Augustine Graham M. Benoit Arpita Bose Camila A. Alire Judith M. Auth Phyllis Bentley Laura S. -

Illuminating the Past

Published by PhotoBook Press 2836 Lyndale Ave. S. Minneapolis, MN 55408 Designed at the School of Information and Library Science University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 216 Lenoir Drive CB#3360, 100 Manning Hall Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3360 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is committed to equality of educational opportunity. The University does not discriminate in o fering access to its educational programs and activities on the basis of age, gender, race, color, national origin, religion, creed, disability, veteran’s status or sexual orientation. The Dean of Students (01 Steele Building, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-5100 or 919.966.4042) has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the University’s non-discrimination policies. © 2007 Illuminating the Past A history of the first 75 years of the University of North Carolina’s School of Information and Library Science Illuminating the past, imagining the future! Dear Friends, Welcome to this beautiful memory book for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Information and Library Science (SILS). As part of our commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the founding of the School, the words and photographs in these pages will give you engaging views of the rich history we share. These are memories that do indeed illuminate our past and chal- lenge us to imagine a vital and innovative future. In the 1930’s when SILS began, the United States had fallen from being the land of opportunity to a country focused on eco- nomic survival. The income of the average American family had fallen by 40%, unemployment was at 25% and it was a perilous time for public education, with most communities struggling to afford teachers and textbooks for their children. -

Online Finding

COLLECTIONS OF CORfillSPONDENCE hKD ~~NUSCRIPT DOCill1ENTS ') SOURCE: Gift of M. F., Tauber, 1966-1976; 1978; Gift of Ellis Mount, 1979; Gift of Frederick Tauber, 1982 SUBJECT: libraries; librarianship DATES COVERED: 1935- 19.Q2:;...·_· NUMBER OF 1TEHS; ca. 74,300- t - .•. ,..- STATUS: (check anoroor La te description) Cataloged: Listed:~ Arranged:-ll- Not organized; _ CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes> or shelves) vc Bound:,...... Boxed:231 Stro r ed; 11 tape reels LOCATION:- (Library) Rare Book and CALL~NtJHBER Ms Coll/Tauber Manuscript RESTRICTIONS ON USE None --.,.--....---------------.... ,.... - . ) The professional correspondence and papers of Maurice Falcolm Tauber, 1908- 198~ Melvil!. DESCRIPTION: Dewey Professor' of Library Service, C9lumbia University (1944-1975). The collection documents Tauber's career at Temple University Library, University of Chicago Graduate LibrarySghooland Libraries, and ColumbiaUniver.sity Libra.:t"ies. There are also files relating to his.. ~ditorship of College' and Research Libraries (1948...62 ). The collection is,d.ivided.;intot:b.ree series. SERIESL1) G'eneral correspondence; inchronological or4er, ,dealing with all aspects of libraries and librarianship•. 2)' Analphabet1cal" .subject fi.~e coni;ainingcorrespQndence, typescripts, .. mJnieographed 'reports .an~,.::;~lated printed materialon.allaspects of libraries and. librarianship, ,'lith numerou§''':r5lders for the University 'ofCh1cago and Columbia University Libraries; working papers for many library surveys conducted by Tauber, including 6 boxes of material relating to his survey of Australian libraries; and 2 boxes of correspondence and other material for Tauber and Lilley's ,V.S. Officeof Education Project: Feasibility Study Regarding the Establishment of an Educational Media Research Information Service (1960); working papers of' many American Library Association, American National Standards~J;:nstituteand other professional organization conferences and committee meetings. -

Louis Round Wilson Academy Formed Inaugural Meeting Held in Chapel Hill

$1.5 million bequest to benefit SILS technology Inside this Issue Dean’s Message ....................................... 2 Dr. William H. and Vonna K. Graves have pledged a gift of $1.5 Faculty News ............................................. 8 million to the School of Information and Library Science (SILS). The Honor Roll of Donors ........................... 13 bequest, SILS’ largest to date, is intended to enhance the School’s Student News ..........................................18 technology programs and services. See page 3. Alumni News ...........................................23 SCHOOL OF INFORMATION AND LIBRARY SCIENCE @ The SCHOOL of INFORMATION and LIBRARY SCIENCE • TheCarolina UNIVERSITY of NORTH CAROLINA at CHAPEL HILL Spring 2006 http://sils.unc.edu Number 67 Louis Round Wilson Academy Formed Inaugural meeting held in Chapel Hill Citizens around “Our faculty, and the world are becoming the faculty of every more aware that they leading University often need a trusted in the world, real- guide to help sort and izes that the role of substantiate the infor- the 21st and 22nd mation they require. century knowledge Faculty members at the professional must be School of Information carefully shaped,” and Library Science said Dr. José-Marie (SILS) agree that Griffiths, dean leading institutions are of SILS and the obliged to review and Lippert Photography Photo by Tom founding chair of design anew roles and Members of the Louis Round Wilson Academy and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School the Louis Round models for Knowledge Pro- of Information and Library Science faculty following the formal induction ceremony in the rotunda of Wilson Academy. the Rare Books Room of the Louis Round Wilson Library. -

Spring 2010 Jottingsand DIGRESSIONS

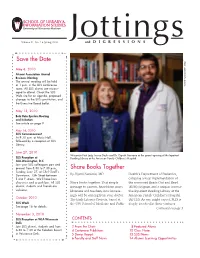

SCHOOL OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION STUDIES Volume 41, No. 2 • Spring 2010 Jottingsand DIGRESSIONS Save the Date JOHN MANIACI/UW HEALTH May 6, 2010 Alumni Association Annual Business Meeting The annual meeting will be held at 1 p.m. in the SLIS conference room. All SLIS alumni are encour- aged to attend. Check the SLIS Web site for an agenda, proposed changes to the SLIS constitution, and the Executive Board ballot. May 13, 2010 Beta Beta Epsilon Meeting and Initiation See article on page 9. May 16, 2010 SLIS Commencement At 9:30 a.m. at Music Hall, followed by a reception at SLIS Library. June 27, 2010 Wisconsin First Lady Jessica Doyle and Dr. Dipesh Navsaria at the grand opening of the Inpatient SLIS Reception at Reading Library at the American Family Children’s Hospital. ALA-Washington, D.C. Join your SLIS colleagues past and present from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m., Share Books Together Sunday, June 27, at Chef Geoff’s Downtown, 13th Street between By Dipesh Navsaria, MD Health’s Department of Pediatrics, E and F streets. We’ll have hors comprise a local implementation of d’oeuvres and a cash bar. All SLIS Share books together. That simple the renowned Reach Out and Read alumni, students and friends are message to parents, heard from many (ROR) program and a unique, innova- welcome. librarians and teachers, now increas- tive Inpatient Reading Library at the ingly will be coming from your doctor. American Family Children’s Hospital October 2010 The Early Literacy Projects, based at (AFCH). As one might expect, SLIS is SLIS Week the UW School of Medicine and Public deeply involved in these ventures. -

Books in My Life. the Center for the Book/Viewpoint Series No. 14

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 263 586 CS 209 395 AUTHOR Downs, Robert B. TITLE Books in My Life. The Center for the Book/Viewpoint Series No. 14. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Center for the Book. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8444-0509-4 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 19p. PUB TYPE 'viewpoints (120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Attitude Change; *Books; Change Strategies; *Influences; Libraries; *Literary History; *Literature; Literature Appreciation; Publications; *Reading Interests; World Literature ABSTRACT As part of the Center for the Book's Viewpoint Series, this booklet considers the impact of books on history and civilization and their influence on personal lifeas well. Beginning with a preface by John Y. Cole, Executive Director of the Center for the Book, the booklet discusses writer Robert B. Down's favorite childhood books and his interest in books and libraries that led to his writing a number of books on the theme of the influence of books, including "Books That Changed the World"; "Famous American Books"; "Famous Books, Ancient and Medi:wain; "Famous Books Since 1492"; "Books That Changed America"; "Famous Books, Great Writings in the History of Civilization"; "Books That Changed the South"; "In Search of New Horizons, Epic Tales of Travel and Exploration"; and "Landmarks in Science, Hippocrates to Carson." The booklet lists the two factors considered when including books in such collections and concludes with an examination of attempts made by other critics to assess the influence of books. (EL) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** ROBERT B. DOWNS LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1985 U.S. -

ACRL News Issue (B) of College & Research Libraries

derson, David W. Heron, William Heuer, Peter ACRL Amendment Hiatt, Grace Hightower, Sr. Nora Hillery, Sam W. Hitt, Anna Hornak, Marie V. Hurley, James Defeated in Council G. Igoe, Mrs. Alice Ihrig, Robert K. Johnson, H. G. Johnston, Virginia Lacy Jones, Mary At the first meeting of the ACRL Board of Kahler, Frances Kennedy, Anne E. Kincaid, Directors on Monday evening, June 21, the Margaret M. Kinney, Thelma Knerr, John C. Committee on Academic Status made known Larsen, Mary E. Ledlie, Evelyn Levy, Joseph its serious reservations about the proposed Pro W. Lippincott, Helen Lockhart, John G. Lor gram of Action of the ALA Staff Committee on enz, Jean E. Lowrie, Robert R. McClarren, Jane Mediation, Arbitration and Inquiry. It moved S. McClure, Stanley McElderry, Jane A. Mc that the Board support an amendment to the Gregor, Elizabeth B. Mann, Marion A. Milc Program which would provide that the staff zewski, Eric Moon, Madel J. Morgan, Effie Lee committee “shall not have jurisdiction over mat Morris, Florrinell F. Morton, Margaret M. Mull, ters relating to the status and problems of aca William D. Murphy, William C. Myers, Mrs. demic librarians except on an interim basis,” Karl Neal, Mildred L. Nickel, Eileen F. Noo and that the interim should last only through nan, Philip S. Ogilvie, A. Chapman Parsons, August 31, 1972. It also stipulated that proce Richard Parsons, Anne Pellowski, Mary E. dures be set up by ACRL to protect the rights Phillips, Margaret E. Poarch, Patricia Pond, of academic librarians. (For the full amend Gary R. Purcell, David L. -

76Th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association

AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 76th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association At Kansas City, Missouri June 23-29, 1957 AMERICAi\; LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON STREET CHICAGO 11. ILLINOIS A M E R I C A N L I B R A R Y A S S O C I A T JI O N 76th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association l{ansas City, Missouri June 23-29, 1957 • AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON STREET CHICAGO 11, ILLINOIS 1957 ALA Conference Proceedings Kansas City, Missouri GENERAL SESSIONS First General Session. I Second General Session. 2 Third General Session. 3 Membership Meeting . 5 COUNCIL SESSIONS ALA Council . 7 PRE-CONFERENCE INSTITUTES Adult Education Institute ......................................................... 10 "Opportunities Unlimited" ....................................................... 11 TYPE-OF-LIBRARY DIVISIONS American Association of School Librarians .......................................... 12 Association of College and Research Libraries ........................................ 16 Committee on Foundation Grants .............................................. 17 Junior College Libraries Section .............................................. 17 Libraries of Teacher-Training Institutions Section ............................... 18 Pure and Applied Science Section. 18 Committee on Rare Books, Manuscripts and Special Collections .................. 19 University Libraries Section...... 19 Association of Hospital and Institution Libraries ...................................... 20 Public -

North Carolina Libraries Face the Depression

Made available courtesy of North Carolina Library Association: http://www.nclaonline.org/ ***Reprinted with permission. No further reproduction is authorized without written permission from North Carolina Library Association. This version of the document is not the version of record. Figures and/or pictures may be missing from this format of the document.*** North Carolina Libraries ! Face the Depression: A Regional Field Agent and the "Bell Cow" State, 1930-36 by James V. Carmichael, Jr. ibrarians, like other profession suited from hard times in such areas as appropriation for the North Carolina li als, flatter themselves with the interlibrarycooperationandlending.2This brary Commission was received. Atlanta notion that their problems are article examines the social and political librarian Julia T. Rankin admitted to Annie ,......_ ... unique. The generational arro context of North Carolina library affairs Ross, North Carolina Library Commission gance that comes with an ex during the same era and the effect that director, that "Your news fills us with so panded knowledge base, new "field work" - a predecessor of much envy that we can hardly congratu te(:nnIOi()gy, and professional respectabil~ "consultancy" - had on them. late you/'s By 1929-30 North Carolina's ity often obscures the similarities of their In one apocryphal story, a southern $24,900 appropriation, used to support 'j'>£Lu",w.vuwith that oftheir forebears. Thus, farmer interviewed by a Federal Writers' the traveling library program, state field cuts in the serials budgets of most Project worker during the Great Depres work, and rudimentary public library ex universities, the closing of big city sion claimed he did not know there was a tension work, was the largest in the South. -

IR 002 416 National Commission on Libraries and Information Science

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 111 362 52 IR 002 416 TITLE National Commission on Libraries and Information Science Mid Atlantic States Regional Hearing, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 21, 1975. Volume One. Scheduled Witnesses. INSTITUTION National Commission on Tibraries and Information Science, lashington, D.C. PUB DATE 21 May 75 NOTE 214p.; For related documents see IR 002 417 and 18 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$10.78 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Community Information Services; Copyrights; *Federal Programs; Financial Support; Government Role; Information Dissemination; Information Needs; *Information Networks; Information Services; Interlibrary Loans; *Libraries; Library Cooperation; Library Education; Library Networks; Library Role; Library Services; Library Standards; Meetings; *National Programs; Outreach Programs; Program Planning; Public Libraries; Technology; University Libraries IDENTIFIERS Mid Atlantic States; *National Commission Libraries Information Science; NCLIS ABSTRACT This is the first of two volumes of written testimony presented to the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science (NCLIS) at its Mid-Atlantic States Regional Hearingheld May 21, 1975 at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Statementsare provided by public, academic, research, special, regional, state, and school librarians, as well as by information scientists,congressmen, educators, and officials of associations, library schools, commercial information services, and state and local governments. The majority of the testimony is in response to the second draft report ofNCLIS and touches upon such subjects as the nationalprogram, networks, the need for funding, reaching the non-user, the role of the library, information and referral services, standards, bibliographic control, the role of government at all levels, education of librarians, information needs, new technology, services to children, library cooperation and shared resources, categorical aidprograms, copyright and copying, the White House conference, and the role of Library of Congress.