Organizing the Library's Support UNIVERSITY of ILLINOIS LIBRARY URBANA-GHAMPAIQN F~ .Or M.T.Rt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Libraries, October 1964

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1964 Special Libraries, 1960s 10-1-1964 Special Libraries, October 1964 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1964 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, October 1964" (1964). Special Libraries, 1964. 8. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1964/8 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1964 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL LIBRARIES ASSOCIATION Putting Knowledge to Work OFFICERS DIRECTORS President WILLIAMK. BEATTY WILLIAMS. BUDINGTON Northwestern University Medic'il The John Crerar Library, Chicago, Illinois School, Chicago, Illinois President-Elect HELENEDECHIEF ALLEENTHOMPSON Canadian Nafional Railwa~r, General Electric Company, Sun Jose, California Montreal, Quebec Advisory Council Chairman JOAN M. HUTCHINSON(Secretary) Research Center, Diamond Alkali LORNAM. DANIELLS Company, Painesville, Ohio Harvard Business School, Boston, Massachusetl~ KENNETHN. METCALF Advisory Council Chairman-Elect Henry Ford Museum and Greei~. HERBERTS. WHITE field Village, Dearborn, Michigan NASA Facility, Documentation, Inc., Bethesda, Maryland MRS.ELIZABETH B. ROTH Treasurer Standard Oil Company of Cali- JEANE. FLEGAL fornia, San Francisco, California Union Carbide Corp., New YorR, New York MRS. DOROTHYB. SKAU Immediate Past-President Southern Regional Research Lab- MRS.MILDRED H. BRODE oratory, U.S. Department of Agri- David Taylor Model Basin, Washington, D. C. culture. New Orleans, Louirirrna EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: BILL M. -

2007–2008 Donor Roster

American Library Association 2007–2008 Donor Roster The American Library Association is a 501(c)(3) charitable and educational organization. ALA advocates funding and policies that support libraries as great democratic institutions, serving people of every age, income level, location, ethnicity, or physical ability, and providing the full range of information resources needed to live, learn, govern, and work. Through the generous support of our members and friends, ALA is able to carry out its work as the leading advocate for the public’s right to a free and open information society. We seek ongoing philanthropic support so that we continue to advocate on behalf of libraries and library users, provide scholarships to students preparing to enter the library profession, promote literacy and community outreach programs, and encourage reading and continuing education in communities across America. Contributions and tax-deductible bequests in any amount are invited. For more information, contact the ALA Development Office at 800.545.2433, or [email protected]. Marilyn Ackerman Jewel Armstrong Player Gary S. Beer Miriam A. Bolotin Heather J. Adair Mary J. Arnold Kathleen Behrendt Nancy M. Bolt Nancy L. Adam Judy Arteaga Penny M. Beile Ruth Bond Martha C. Adamson Joan L. Atkinson Steven J. Bell Lori Bonner Sharon K. Adley Sharilynn A. Aucoin Valerie P. Bell Roberta H. Borman Elizabeth Ahern Sahagian Rita Auerbach Robert J. Belvin Paula Bornstein Rosie L. Albritton Mary Augusta Thomas Betty W. Bender Eileen K. Bosch Linda H. Alexander Rolf S. Augustine Graham M. Benoit Arpita Bose Camila A. Alire Judith M. Auth Phyllis Bentley Laura S. -

Spring 2010 Jottingsand DIGRESSIONS

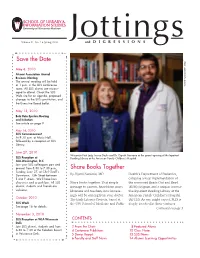

SCHOOL OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION STUDIES Volume 41, No. 2 • Spring 2010 Jottingsand DIGRESSIONS Save the Date JOHN MANIACI/UW HEALTH May 6, 2010 Alumni Association Annual Business Meeting The annual meeting will be held at 1 p.m. in the SLIS conference room. All SLIS alumni are encour- aged to attend. Check the SLIS Web site for an agenda, proposed changes to the SLIS constitution, and the Executive Board ballot. May 13, 2010 Beta Beta Epsilon Meeting and Initiation See article on page 9. May 16, 2010 SLIS Commencement At 9:30 a.m. at Music Hall, followed by a reception at SLIS Library. June 27, 2010 Wisconsin First Lady Jessica Doyle and Dr. Dipesh Navsaria at the grand opening of the Inpatient SLIS Reception at Reading Library at the American Family Children’s Hospital. ALA-Washington, D.C. Join your SLIS colleagues past and present from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m., Share Books Together Sunday, June 27, at Chef Geoff’s Downtown, 13th Street between By Dipesh Navsaria, MD Health’s Department of Pediatrics, E and F streets. We’ll have hors comprise a local implementation of d’oeuvres and a cash bar. All SLIS Share books together. That simple the renowned Reach Out and Read alumni, students and friends are message to parents, heard from many (ROR) program and a unique, innova- welcome. librarians and teachers, now increas- tive Inpatient Reading Library at the ingly will be coming from your doctor. American Family Children’s Hospital October 2010 The Early Literacy Projects, based at (AFCH). As one might expect, SLIS is SLIS Week the UW School of Medicine and Public deeply involved in these ventures. -

76Th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association

AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 76th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association At Kansas City, Missouri June 23-29, 1957 AMERICAi\; LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON STREET CHICAGO 11. ILLINOIS A M E R I C A N L I B R A R Y A S S O C I A T JI O N 76th Annual Conference Proceedings of the American Library Association l{ansas City, Missouri June 23-29, 1957 • AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 50 EAST HURON STREET CHICAGO 11, ILLINOIS 1957 ALA Conference Proceedings Kansas City, Missouri GENERAL SESSIONS First General Session. I Second General Session. 2 Third General Session. 3 Membership Meeting . 5 COUNCIL SESSIONS ALA Council . 7 PRE-CONFERENCE INSTITUTES Adult Education Institute ......................................................... 10 "Opportunities Unlimited" ....................................................... 11 TYPE-OF-LIBRARY DIVISIONS American Association of School Librarians .......................................... 12 Association of College and Research Libraries ........................................ 16 Committee on Foundation Grants .............................................. 17 Junior College Libraries Section .............................................. 17 Libraries of Teacher-Training Institutions Section ............................... 18 Pure and Applied Science Section. 18 Committee on Rare Books, Manuscripts and Special Collections .................. 19 University Libraries Section...... 19 Association of Hospital and Institution Libraries ...................................... 20 Public -

IR 002 416 National Commission on Libraries and Information Science

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 111 362 52 IR 002 416 TITLE National Commission on Libraries and Information Science Mid Atlantic States Regional Hearing, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, May 21, 1975. Volume One. Scheduled Witnesses. INSTITUTION National Commission on Tibraries and Information Science, lashington, D.C. PUB DATE 21 May 75 NOTE 214p.; For related documents see IR 002 417 and 18 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$10.78 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS Community Information Services; Copyrights; *Federal Programs; Financial Support; Government Role; Information Dissemination; Information Needs; *Information Networks; Information Services; Interlibrary Loans; *Libraries; Library Cooperation; Library Education; Library Networks; Library Role; Library Services; Library Standards; Meetings; *National Programs; Outreach Programs; Program Planning; Public Libraries; Technology; University Libraries IDENTIFIERS Mid Atlantic States; *National Commission Libraries Information Science; NCLIS ABSTRACT This is the first of two volumes of written testimony presented to the National Commission on Libraries and Information Science (NCLIS) at its Mid-Atlantic States Regional Hearingheld May 21, 1975 at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Statementsare provided by public, academic, research, special, regional, state, and school librarians, as well as by information scientists,congressmen, educators, and officials of associations, library schools, commercial information services, and state and local governments. The majority of the testimony is in response to the second draft report ofNCLIS and touches upon such subjects as the nationalprogram, networks, the need for funding, reaching the non-user, the role of the library, information and referral services, standards, bibliographic control, the role of government at all levels, education of librarians, information needs, new technology, services to children, library cooperation and shared resources, categorical aidprograms, copyright and copying, the White House conference, and the role of Library of Congress. -

1896 Sargent, John F. Supplement to Reading for the Young 1901 Massachusetts Library Club

13/2/14 Publishing Books and Pamphlets A.L.A. Publications, 1896-1965, 1967, 1969- Box 1: 1896 Sargent, John F. Supplement to Reading for the Young 1901 Massachusetts Library Club. Catalogue of Annual Reports contained in the Massachusetts Public Documents. paperbound 1905 American Library Association, List of Subject Headings for Use in Dictionary Catalogs. Second Edition, Revised Smith, Charles Wesley, Library Conditions in the Northwest. paperbound Tarbell, Mary Anna, A Village Library in Massachusetts; The Story of Its Upbuilding. paperbound 1908 Marvin, Cornelia, ed. Small Library Buildings 1909 Hooper, Louisa M. Selected List of Music and Books About Music for Public Libraries. paperbound 1910 Jeffers, Le Roy. Lists of Editions Selected for Economy in Book Buying Wyer, J. I., Jr. U.S. Government Documents in Small Libraries 1911 American Library Association. List of Subject Headings for Use in Dictionary Catalogs. Third Edition, Revised by Mary Josephine Briggs 1912 Reid, Marguerite and John G. Moulton (compilers). Aids in Library Work with Foreigners 1913 Jeffers, Le Roy, comp. List of Economical Editions. Second Edition, Revised, paperbound Jone, Edith Kathleen. A Thousand Books for the Hospital Library. paperbound 1914 Hall, Mary E. Vocational Guidance Through the Library. paperbound Wilson, Martha. Books for High School. paperbound 1915 Booth, Mary Josephine. Lists of Material Which May be Obtained Free or At Small Cost. paperbound Hitchler, Theresa. Cataloging for Small Libraries. Revised Edition Meyer, H.H.B. A Brief Guide to the Literature of Shakespeare. paperbound 1916 1 13/2/14 Mann, Margaret. Subject Headings for Use in Dictionary Catalogs of Juvenile Books 1917 American Library Association. -

Rocks in the Whirlpool

Rocks in the Whirlpool Kathleen de la Peña McCook Distinguished University Professor University of South Florida School of Library and Information Science May, 2002 Author: Kathleen de la Peña McCook is Distinguished University Professor at the School of Library and Information Science, University of South Florida, Tampa. Paper submitted to the Executive Board of the American Library Association at the June 14, 2002 Annual Conference. Special gratitude is due to Nancy Kranich, ALA President, 2000-2001 and Mary Ghikas, American Library Association, Associate Executive Director for initiating this project and reviewing and commenting upon numerous versions. Introduction 1. Toward the Concept of Access A. Almost overnight, the organization became a public service organization. B. Extension and Adult Education C. A Federal Role for Libraries D. Role of the Library in the Post-War World E. Federal Aid Era 2. Downstream Access A. Literacy and Lifelong Learning B. African – Americans C. ALA, Outreach, and Equity: "Every Means at Its Disposal" D. People with Disabilities E. Services to Poor and Homeless People 3. Protecting and Extending Access A. Intellectual Freedom and Libraries: An American Value B. Toward a Conceptual Foundation for a National Information Policy C. Freedom and Equality of Access to Information D. Special Committee on Freedom and Equality of Access to Information E. Your Right to Know: Librarians Make It Happen F. ALA Goal 2000—Intellectual Participation G. ALAction 2005 and "Equity of Access H. Congresses on Professional Education and Core Values Task Forces 4. Upstream Access A. An Information Agenda for the 1980s B. The library community should actively participate in the formulation and implementation of national information policies. -

ACRL News Issue (B) of College & Research Libraries

ACRL Board of Directors ANNUAL CONFERENCE membership poll concerning such a levy. The May 1972 issue of CRL News had CHICAGO, ILLINOIS, 1972 carried a special insert which provided the membership an opportunity to express their opinion on the matter, asking whether they M i n u t e s were in favor of the assessment or opposed to Monday, June 26, 1972—10:00-11:30 a .m . it believing the office should be funded from the ALA budget. Space was also provided on Present: President, Joseph H. Reason; Vice- the card for other preferences or comments. President and President-Elect, Russell Shank; Mr. Beard reported that the response to the Past President, Anne C. Edmonds; Directors- poll had been very poor, with only 732 replies at-Large, Mark M. Gormley, Norman E. Tanis, (6.7 percent), out of a total membership of David C. Weber; Directors on ALA Council, 10,872. Of those responding, 149 voted in fa Page Ackerman, Evan I. Farber, James F. Hol vor of the assessment, 424 were opposed to the ly, Robert K. Johnson, Roscoe Rouse; Chair assessment and believed the office should be men of Sections, Carl R. Cox, Hal C. Stone, funded from the ALA budget, 116 were op Lee Ash, Wolfgang M. Freitag, Ralph H. posed to the office and/or faculty status, 20 Hopp; Vice-Chairmen and Chairmen-Elect of were in favor only if funding from ALA were Sections, John R. Beard, William J. Hoffman, not forthcoming, 4 were in favor of a smaller Howard L. Applegate, Alice D. -

13/2/14 Publishing Services Books and Pamphlets ALA Publications

13/2/14 Publishing Services Books and Pamphlets A.L.A. Publications, 1876- Box 1: Reprint Series Number 1: The National Library Problem Today, Ernest Cushing Richardson, 1905 Number 2: Library Conditions in the Northwest, by Charles Wesley Smith, 1905 Number 4: The Library of Congress as a National Library, by Herbert Putnam, 1905 1896 Sargent, John F. Supplement to Reading for the Young 1901 Massachusetts Library Club. Catalogue of Annual Reports contained in the Massachusetts Public Documents. paperbound 1905 American Library Association, List of Subject Headings for Use in Dictionary Catalogs. Second Edition, Revised 1908 Marvin, Cornelia, ed. Small Library Buildings 1909 Hooper, Louisa M. Selected List of Music and Books About Music for Public Libraries. paperbound 1910 Jeffers, Le Roy. Lists of Editions Selected for Economy in Book Buying 1911 American Library Association. List of Subject Headings for Use in Dictionary Catalogs. Third Edition, Revised by Mary Josephine Briggs 1913 Jeffers, Le Roy, comp. List of Economical Editions. Second Edition, Revised, paperbound Jone, Edith Kathleen. A Thousand Books for the Hospital Library. paperbound 1914 Material on Geography; Which May Be Obtained Free or at Small Cost, compiled by Mary J. Booth Hall, Mary E. Vocational Guidance Through the Library. paperbound Wilson, Martha. Books for High School. paperbound 1915 Booth, Mary Josephine. Lists of Material Which May be Obtained Free or At Small Cost. paperbound Curtis, Florence Rising. The Collection of Social Survey Material. paperbound Hitchler, Theresa. Cataloging for Small Libraries. Revised Edition Meyer, H.H.B. A Brief Guide to the Literature of Shakespeare. paperbound 1916 1 13/2/14 2 Mann, Margaret. -

2008–2009 Donor Roster

American Library Association 2008–2009 Donor Roster The American Library Association is a 501(c)(3) charitable and educational organization. ALA advocates funding and policies that support libraries as great democratic institutions, serving people of every age, income level, location, ethnicity, or physical ability, and providing the full range of information resources needed to live, learn, govern, and work. Through the generous support of our members and friends, ALA is able to carry out its work as the leading advocate for the public’s right to a free and open information society. We seek ongoing philanthropic support so that we continue to advocate on behalf of libraries and library users, provide scholarships to students preparing to enter the library profession, promote literacy and community outreach programs, and encourage reading and continuing education in communities across America. Contributions and tax-deductible bequests in any amount are invited. For more information, contact the ALA Development Office at 800.545.2433, or [email protected]. Ismail Abdullahi Joan L. Atkinson Sherrie S. Bergman Margaret Bowe Chad P. Abel-Kops Sharilynn A. Aucoin Natasha Bergon-Michelson Kathryn R. Boyens Charles Abell Rita Auerbach Mary Linn Bergstrom Yvonne D. Boyer Deborah Abner Rolf S. Augustine Mary Rinato Berman Julie Boyle Marilyn Ackerman Brice W. Austin Alan Bern Patricia Bozeman Elaine S. Ackroyd-Kelly Judith M. Auth Dorothy C. Bertsch Diana V. Braddom Heather J. Adair John Louis Ayala June M. Besek Lynne E. Bradley James Agee Judith A. Babcock Jonathan R. Betz-Zall Martha G. Bradshaw Joan Diane Airoldi Nadine L. Baer Sandra Beyer William B. -

Special Libraries, March 1968

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1968 Special Libraries, 1960s 3-1-1968 Special Libraries, March 1968 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1968 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, March 1968" (1968). Special Libraries, 1968. 3. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1968/3 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1968 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROGRESS IN NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE SPECTROSCOPY, Volume 3 Edited by J. W. Emsley, Durham University; J. Feeney, Varian Associates, Ltd.; and L. Sutcliffe, Liverpool University, all England 420 pages, 161 illustrations $18.00 THE PAPER-MAKING MACHINE: Its Invention, Evolution and Development By R. H. Clapperton, British Paper and Board Makers Association, England 366 pages, 175 illustrations $32.00 BlOGENESlS OF NATURAL COMPOUNDS, Second Edition, revised and enlarged Edited by Peter Bernfeld, Bio-Research Institute, Cambridge, Massachusetts 1,204 pages, 598 illustrations $44.00 COLLlSlONAL ACTIVATION IN GASES INTERNATIONAL ENCYCLOPEDIA OF PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY AND CHEMICAL PHYSICS, TOPIC 19: GAS KINETICS, VOLUME 3 By Brian Stevens, Sheffield University, England 248 pages, 52 illustrations $14.00 UREA AS A PROTEIN SUPPLEMENT Edited by Michael H. Briggs, Analytical 1-aboratories Ltd., England 480 pages, 42 illustrations $18.00 ENTOMOLOGICAL PARASITOLOGY FOUNDATIONS OF EUCLIDEAN The Relations Between Entomology AND NON-EUCLIDEAN and the Medical Sciences GEOMETRIES ACCORDING TO INTERNATIONAL SERIES OF F. -

Special Libraries, July-August 1966

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1966 Special Libraries, 1960s 7-1-1966 Special Libraries, July-August 1966 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1966 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, July-August 1966" (1966). Special Libraries, 1966. 6. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1966/6 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1966 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. special libraries If your plans don't include consultation with Information Technology Specialists ... change them. For more than a decade, Herner and Company has been providing consultation in library programs and services for industrial, governmental and educational facilities. Its mature staff has a wide range of experience in applying the skills and methodologies of information processing to various scientific disciplines. Herner and Company is proud of its record of problem-solving innovations to meet client requirements in the following areas: Design of Libraries and Related lnformation Programs / Operation of Programs / Evaluation of Pro- grams / Library Mechanization / Performance of Special Services for Libraries, including Physical Planning, Staff Recruitment and Training, Development of Collections, Acquisition, Cataloging, Abstracting, Indexing, Coding and Processing. To discuss a practical and economical answer to your library requirements, or any information area, write or call . H E R N E R C O M PAN Y 2431 K ST., N.W., WASH., D.