Copyright by Harold Glenn Revelson 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract Julius Theodor (1849–1923)

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract This article is a biography of the prominent scholar of Aggadic literature, Rabbi Dr Julius Theodor (1849–1923). It describes Theodor’s childhood and family and his formative years spent studying at the Breslau Rabbinical Seminary. It explores the thirty one years he served as a rabbi in the town of Bojanowo, and his final years in Berlin. The article highlights The- odor’s research and includes a list of his publications. Specifically, it focuses on his monumental, pioneering work preparing a critical edition of Bereshit Rabbah (completed by Chanoch Albeck), a project which has left a deep imprint on Aggadic research to this day. Der folgende Artikel beinhaltet eine Biographie des bedeutenden Erforschers der aggadischen Literatur Rabbiner Dr. Julius Theodor (1849–1923). Er beschreibt Theodors Kindheit und Familie und die ihn prägenden Jahre des Studiums am Breslauer Rabbinerseminar. Er schil- dert die einunddreissig Jahre, die er als Rabbiner in der Stadt Bojanowo wirkte, und seine letzten Jahre in Berlin. Besonders eingegangen wird auf Theodors Forschungsleistung, die nicht zuletzt an der angefügten Liste seiner Veröffentlichungen ablesbar ist. Im Mittelpunkt steht dabei seine präzedenzlose monumentale kritische Edition des Midrasch Bereshit Rabbah (die Chanoch Albeck weitergeführt und abgeschlossen hat), ein Werk, das in der Erforschung aggadischer Literatur bis heute nachwirkende Spuren hinterlassen hat. Julius Theodor (1849–1923) is one of the leading experts of the Aggadic literature. His major work, a scholarly edition of the Midrash Bereshit Rabbah (BerR), completed by Chanoch Albeck (1890–1972), is a milestone and foundation of Jewish studies research. His important articles deal with key topics still relevant to Midrashic research even today. -

A Clergy Resource Guide

When Every Need is Special: NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING A Clergy Resource Guide For the best in child, family and senior services...Think JSSA Jewish Social Service Agency Rockville (Wood Hill Road), 301.838.4200 • Rockville (Montrose Road), 301.881.3700 • Fairfax, 703.204.9100 www.jssa.org - [email protected] WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING PREFACE This February, JSSA was privileged to welcome 17 rabbis and cantors to our Clergy Training Program – When Every Need is Special: Navigating Special Needs in the Synagogue Environment. Participants spanned the denominational spectrum, representing communities serving thousands throughout the Washington region. Recognizing that many area clergy who wished to attend were unable to do so, JSSA has made the accompanying Clergy Resource Guide available in a digital format. Inside you will find slides from the presentation made by JSSA social workers, lists of services and contacts selected for their relevance to local clergy, and tachlis items, like an ‘Inclusion Check‐list’, Jewish source material and divrei Torah on Special Needs and Disabilities. The feedback we have received indicates that this has been a valuable resource for all clergy. Please contact Rabbi James Kahn or Natalie Merkur Rose with any questions, comments or for additional resources. L’shalom, Rabbi James Q. Kahn, Director of Jewish Engagement & Chaplaincy Services Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8356 Natalie Merkur Rose, LCSW‐C, LICSW, Director of Jewish Community Outreach Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8319 WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING RESOURCE GUIDE: TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: SESSION MATERIALS FOR REVIEW PAGE Program Agenda ......................................................................................................... -

Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File

Intellectuals Displaced from Fascist Italy © Firenze University Press 2019 Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File «When, in 1938, I delivered my last lecture at this University, as a libero docente Link to other connected Lives on the [lecturer with official certification to teach at the university] of Hebrew language move: and literature I would not have believed...»: in this way, Elia Samuele Artom opened Emanuele Menachem the commemoration of his brother-in-law, Umberto Cassuto, on 28 May 1952 in Artom 1 Enzo Bonaventura Florence, where he was just passing through . Umberto Cassuto The change that so many lives, like his own, had to undergo as a result of anti- Anna Di Gioacchino Cassuto Jewish laws was radical. Artom embarked for Mandatory Palestine in September Enrico Fermi Kalman Friedman 1939, with his younger son Ruben. Upon arrival he found a land that was not simple, Dante Lattes whose ‘promise’ – at the center of the sources of tradition so dear to him – proved Alfonso Pacifici David Prato to be far more elusive than certain rhetoric would lead one to believe. Giulio Racah His youth and studies Elia Samuele Artom was born in Turin on 15 June 1887 to Emanuele Salvador (8 December 1840 – 17 June 1909), a post office worker from Asti, and Giuseppina Levi (27 August 1849 – 1 December 1924), a kindergarten teacher from Carmagnola2. He immediately showed a unique aptitude for learning: after being privately educated,3 he obtained «the high school honors diploma» in 1904; he graduated in literature «with full marks and honors» from the Facoltà di Filosofia e 1 Elia Samuele Artom, Umberto Cassuto, «La Rassegna mensile di Israel», 18, 1952, p. -

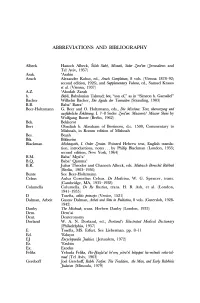

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

The Jew of Celsus and Adversus Judaeos Literature

ZAC 2017; 21(2): 201–242 James N. Carleton Paget* The Jew of Celsus and adversus Judaeos literature DOI 10.1515/zac-2017-0015 Abstract: The appearance in Celsus’ work, The True Word, of a Jew who speaks out against Jesus and his followers, has elicited much discussion, not least con- cerning the genuineness of this character. Celsus’ decision to exploit Jewish opinion about Jesus for polemical purposes is a novum in extant pagan litera- ture about Christianity (as is The True Word itself), and that and other observa- tions can be used to support the authenticity of Celsus’ Jew. Interestingly, the ad hominem nature of his attack upon Jesus is not directly reflected in the Christian adversus Judaeos literature, which concerns itself mainly with scripture (in this respect exclusively with what Christians called the Old Testament), a subject only superficially touched upon by Celsus’ Jew, who is concerned mainly to attack aspects of Jesus’ life. Why might this be the case? Various theories are discussed, and a plea made to remember the importance of what might be termed coun- ter-narrative arguments (as opposed to arguments from scripture), and by exten- sion the importance of Celsus’ Jew, in any consideration of the history of ancient Jewish-Christian disputation. Keywords: Celsus, Polemics, Jew 1 Introduction It seems that from not long after it was written, probably some time in the late 240s,1 Origen’s Contra Celsum was popular among a number of Christians. Eusebius of Caesarea, or possibly another Eusebius,2 speaks warmly of it in his response to Hierocles’ anti-Christian work the Philalethes or Lover of Truth as pro- 1 For the date of Contra Celsum see Henry Chadwick, introduction to idem, ed. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

The Talmud of Jerusalem

THE TALMUD OP JEEUSALEM. TRANSLATED FOB THE FIRST TIME BY Dr. MOSES SCHWAB, OF THE "iilBLlOTHKqUE NATIOXALR," I'AKIS. .Jit. (>' (.'. VOL. L BEI^AKHOTH[. WILLIAMS AND NOEGATE, 14, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN. 1886. 5 PEEFAGE. The Talmud has very often been spoken of, but is little known. The very great linguistic difficulties, and the vast size of the work, have up to the present time prevented the effecting of more than the translation of the Mishna only into Latin and, later, in German. At the instance of some friends, we have decided upon publishing a complete textual and generally literal version of the Talmud, that historical and religious work which forms a continuation of the Old and even of the New Testament.^ "We are far from laying claim to a perfect translation of all the delicate shades of expression belonging to an idiom so strange and variable, which is a mixture of neo-Hebrew and Chaldean, and concise almost to obscurity. We wish to take every opportunity of improving this work. A general introduction will be annexed, treating of the origin, composition, spirit, and history of the Talmud. This introduction will be accompanied by : 1st. An Alphabetical Index of all the incongruous subjects treated of in this vast and unwieldy Encyclo- paedia; 2nd. An Index of the proper and geographical names; 8rd. Concordantial Notes of the various Bible texts employed, permitting a reference to the commentaries made on them (which will sometimes serve a^ Errata). This general introduction can, for obvious reasons, only appear on the completion of the present version. -

Morgenstern Is a Senior Fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem

Dispersion and the Longing for Zion, 1240-1840 rie orgenstern t has become increasingly accepted in recent years that Zionism is a I strictly modern nationalist movement, born just over a century ago, with the revolutionary aim of restoring Jewish sovereignty in the land of Israel. And indeed, Zionism was revolutionary in many ways: It rebelled against a tradition that in large part accepted the exile, and it attempted to bring to the Jewish people some of the nationalist ideas that were animat- ing European civilization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centu- ries. But Zionist leaders always stressed that their movement had deep historical roots, and that it drew its vitality from forces that had shaped the Jewish consciousness over thousands of years. One such force was the Jewish faith in a national redemption—the belief that the Jews would ultimately return to the homeland from which they had been uprooted. This tension, between the modern and the traditional aspects of Zion- ism, has given rise to a contentious debate among scholars in Israel and elsewhere over the question of how the Zionist movement should be described. Was it basically a modern phenomenon, an imitation of the winter 5762 / 2002 • 71 other nationalist movements of nineteenth-century Europe? If so, then its continuous reference to the traditional roots of Jewish nationalism was in reality a kind of facade, a bid to create an “imaginary community” by selling a revisionist collective memory as if it had been part of the Jewish historical consciousness all along. Or is it possible to accept the claim of the early Zionists, that at the heart of their movement stood far more ancient hopes—and that what ultimately drove the most remarkable na- tional revival of modernity was an age-old messianic dream? For many years, it was the latter belief that prevailed among historians of Zionism. -

Crown and Courts Materials

David C. Flatto on The Crown and the Courts: Separation of Powers in the Early Jewish Im.agination Wednesday February 17, 2021 4 - 5 p.m. Online Register at law.fordham.edu/CrownAndCourts CLE COURSE MATERIALS Table of Contents 1. Speaker Biographies (view in document) 2. CLE Materials The Crown and the Courts: Separation of Powers in the Early Jewish Imagination Panel Discussion Cover, Robert M. THE FOLKTALES OF JUSTICE: TALES OF JURISDICTION (view in document) Cardozo Law Review. Levinson, Bernard M. THE FIRST CONSTITUTION: RETHINKING THE ORIGINS OF RULE OF LAW AND SEPARATION OF POWERS IN LIGHT OF DEUTERONOMY (view in document) Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities. Volume 20. Issue 1 Article 3. The King and I: The Separation of Powers in Early Hebraic Political Theory. (view in document) The Crown and the Courts: Separation of Powers in the Early Jewish Imagination Biographies Moderator: Ethan J. Leib is Professor of Law at Fordham Law School. He teaches in contracts, legislation, and regulation. His most recent book, Friend v. Friend: Friendships and What, If Anything, the Law Should Do About Them, explores the costs and benefits of the legal recognition of and sensitivity to friendship; it was published by Oxford University Press. Leib’s scholarly articles have recently appeared in the Yale Law Journal, Virginia Law Review, Georgetown Law Journal, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, University of Chicago Law Review, California Law Review, and elsewhere. He has also written for a broader audience in the New York Times, USA Today, Policy Review, Washington Post, New York Law Journal, The American Scholar, and The New Republic. -

Appendix: a Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources

Appendix: A Guide to the Main Rabbinic Sources Although, in an historical sense, the Hebrew scriptures are the foundation of Judaism, we have to turn elsewhere for the documents that have defined Judaism as a living religion in the two millennia since Bible times. One of the main creative periods of post-biblical Judaism was that of the rabbis, or sages (hakhamim), of the six centuries preceding the closure of the Babylonian Talmud in about 600 CE. These rabbis (tannaim in the period of the Mishnah, followed by amoraim and then seboraim), laid the foundations of subsequent mainstream ('rabbinic') Judaism, and later in the first millennium that followers became known as 'rabbanites', to distinguish them from the Karaites, who rejected their tradition of inter pretation in favour of a more 'literal' reading of the Bible. In the notes that follow I offer the English reader some guidance to the extensive literature of the rabbis, noting also some of the modern critical editions of the Hebrew (and Aramaic) texts. Following that, I indicate the main sources (few available in English) in which rabbinic thought was and is being developed. This should at least enable readers to get their bearings in relation to the rabbinic literature discussed and cited in this book. Talmud For general introductions to this literature see Gedaliah Allon, The Jews in their Land in the Talmudic Age, 2 vols (Jerusalem, 1980-4), and E. E. Urbach, The Sages, tr. I. Abrahams (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 1987), as well as the Reference Guide to Adin Steinsaltz's edition of the Babylonian Talmud (see below, under 'English Transla tions'). -

Hypocrites Or Pious Scholars? the Image of the Pharisees in Second Temple Period Texts and Rabbinic Literature

HYPOCRITES OR PIOUS SCHOLARS? THE IMAGE OF THE PHARISEES IN SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD TEXTS AND RABBINIC LITERATURE Etka Liebowitz* ABSTRACT: This article focuses upon Josephus’ portrayal of the Pharisees during the reign of Queen Alexandra, relating it to tHeir depiction in other contemporary sources (the New Testament, Qumran documents) as well as rabbinic literature. THe numerous Hostile descriptions of the PHarisees in botH War and Antiquities are examined based upon a pHilological, textual and source-critical analysis. Explanations are tHen offered for the puzzling negative description of tHe PHarisees in rabbinic literature (bSotah 22b), wHo are considered tHe predecessors of the sages. THe Hypocrisy cHarge against tHe PHarisees in Matthew 23 is analyzed from a religious-political perspective and allegorical references to the Pharisees as “Seekers of Smooth Things” in Pesher Nahum are also connected to the Hypocrisy motif. THis investigation leads to tHe conclusion tHat an anti-PHarisee bias is not unique to the New Testament but is also found in JewisH sources from tHe Second Temple period. It most probably reflects the rivalry among the various competing religious/political groups and tHeir struggle for dominance. Who were tHe PHarisees – a small religious sect, an influential political party, or a mass movement? Attempts to define and describe tHe pHenomenon of tHe PHarisees Have aroused considerable scholarly debate for decades.1 THis article will focus upon Josephus’ portrayal of tHe PHarisees during tHe reign of Queen Alexandra in The Judaean War and Judaean Antiquities and attempt to understand How it can sHed ligHt upon tHeir depiction in otHer Second Temple period texts – tHe New Testament (MattHew) and Qumran documents (Pesher Nahum), as well as in rabbinic literature (bSotah). -

Solomon Schechter Between Europe and America* Mirjam Thulin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE https://doi.org/10.14324/111.444.jhs.2016v48.028 provided by UCL Discovery Wissenschaft and correspondence: Solomon Schechter between Europe and America* mirjam thulin Institute of European History, Germany* In 1905, the managing editor of the Jewish Encyclopedia, Isidore Singer (1859–1939), published an article in the journal Ost und West from a “bird’s eye perspective on the development of American Jewry in the last 250 years.” In this historical overview, Singer eventually attested that Jewish scholarship in America had an “absolute dependency on the European motherland.”1 This judgment was based on his disapproving view of the two American rabbinical seminaries that existed at that time. According to Singer, there were still no scholars at the Hebrew Union College (HUC) in Cincinnati of the “already American[-born] generation of Israel.”2 In fact, Singer’s observation was appropriate because it applied to the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTSA) in New York as much as to the HUC.3 Despite the history of Jewish settlement in America, around 1900 1 Isidore Singer, “Eine Vogelschau über die Entwicklung der amerikanischen Juden- heit in den letzten 250 Jahren I”, Ost und West 10–11 (1905): col. 671. Following Singer and general usage, “America” in this article refers to the United States only. Translations from German are mine unless otherwise specified. 2 Ibid., col. 672. 3 In 1901, after the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS) gained a new legal status in the state of New York, the institute was renamed the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (JTSA).