1 Draft 11/28/17 Not for Circulation Without Author's Permission Constructing Justice: the Selective Use of Scripture in Fo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File

Intellectuals Displaced from Fascist Italy © Firenze University Press 2019 Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File «When, in 1938, I delivered my last lecture at this University, as a libero docente Link to other connected Lives on the [lecturer with official certification to teach at the university] of Hebrew language move: and literature I would not have believed...»: in this way, Elia Samuele Artom opened Emanuele Menachem the commemoration of his brother-in-law, Umberto Cassuto, on 28 May 1952 in Artom 1 Enzo Bonaventura Florence, where he was just passing through . Umberto Cassuto The change that so many lives, like his own, had to undergo as a result of anti- Anna Di Gioacchino Cassuto Jewish laws was radical. Artom embarked for Mandatory Palestine in September Enrico Fermi Kalman Friedman 1939, with his younger son Ruben. Upon arrival he found a land that was not simple, Dante Lattes whose ‘promise’ – at the center of the sources of tradition so dear to him – proved Alfonso Pacifici David Prato to be far more elusive than certain rhetoric would lead one to believe. Giulio Racah His youth and studies Elia Samuele Artom was born in Turin on 15 June 1887 to Emanuele Salvador (8 December 1840 – 17 June 1909), a post office worker from Asti, and Giuseppina Levi (27 August 1849 – 1 December 1924), a kindergarten teacher from Carmagnola2. He immediately showed a unique aptitude for learning: after being privately educated,3 he obtained «the high school honors diploma» in 1904; he graduated in literature «with full marks and honors» from the Facoltà di Filosofia e 1 Elia Samuele Artom, Umberto Cassuto, «La Rassegna mensile di Israel», 18, 1952, p. -

Abbreviations and Bibliography

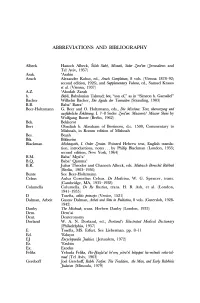

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

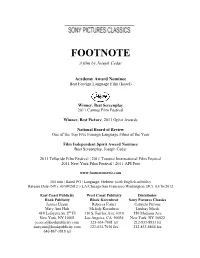

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

Morgenstern Is a Senior Fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem

Dispersion and the Longing for Zion, 1240-1840 rie orgenstern t has become increasingly accepted in recent years that Zionism is a I strictly modern nationalist movement, born just over a century ago, with the revolutionary aim of restoring Jewish sovereignty in the land of Israel. And indeed, Zionism was revolutionary in many ways: It rebelled against a tradition that in large part accepted the exile, and it attempted to bring to the Jewish people some of the nationalist ideas that were animat- ing European civilization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centu- ries. But Zionist leaders always stressed that their movement had deep historical roots, and that it drew its vitality from forces that had shaped the Jewish consciousness over thousands of years. One such force was the Jewish faith in a national redemption—the belief that the Jews would ultimately return to the homeland from which they had been uprooted. This tension, between the modern and the traditional aspects of Zion- ism, has given rise to a contentious debate among scholars in Israel and elsewhere over the question of how the Zionist movement should be described. Was it basically a modern phenomenon, an imitation of the winter 5762 / 2002 • 71 other nationalist movements of nineteenth-century Europe? If so, then its continuous reference to the traditional roots of Jewish nationalism was in reality a kind of facade, a bid to create an “imaginary community” by selling a revisionist collective memory as if it had been part of the Jewish historical consciousness all along. Or is it possible to accept the claim of the early Zionists, that at the heart of their movement stood far more ancient hopes—and that what ultimately drove the most remarkable na- tional revival of modernity was an age-old messianic dream? For many years, it was the latter belief that prevailed among historians of Zionism. -

Copyright by Harold Glenn Revelson 2005

Copyright by Harold Glenn Revelson 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Harold Glenn Revelson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ONTOLOGICAL TORAH: AN INSTRUMENT OF RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL DISCOURSE Committee: ______________________________________ Aaron Bar-Adon, Supervisor ______________________________________ Abraham Marcus ______________________________________ Yair Mazor ______________________________________ Adam Zachary Newton ______________________________________ Esther Raizen ONTOLOGICAL TORAH: AN INSTRUMENT OF RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL DISCOURSE by Harold Glenn Revelson, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2005 With affection to my professors and my dear friends on Shihrur St., Maoz Tzion, Israel Acknowledgements The number of people to whom I owe thanks for their support and help during my academic journey is so large that I could not possibly mention each of them individually. They were equally as important to any success that might have been achieved along the way as those named below. I appreciate all of them greatly. I wish to express thanks to my professors in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. I shall never be able to quantify the invaluable contributions that my adviser, Dr. Aaron Bar-Adon, has made to my academic and personal enrichment. From the day that I met him in July 1991, he has served as an exemplary scholar and teacher. Before the academic year of 1991-1992 began, he invited me to his office for weekly readings in Tanakh, and I have continued to glean from his storehouse of knowledge until today. -

Crown and Courts Materials

David C. Flatto on The Crown and the Courts: Separation of Powers in the Early Jewish Im.agination Wednesday February 17, 2021 4 - 5 p.m. Online Register at law.fordham.edu/CrownAndCourts CLE COURSE MATERIALS Table of Contents 1. Speaker Biographies (view in document) 2. CLE Materials The Crown and the Courts: Separation of Powers in the Early Jewish Imagination Panel Discussion Cover, Robert M. THE FOLKTALES OF JUSTICE: TALES OF JURISDICTION (view in document) Cardozo Law Review. Levinson, Bernard M. THE FIRST CONSTITUTION: RETHINKING THE ORIGINS OF RULE OF LAW AND SEPARATION OF POWERS IN LIGHT OF DEUTERONOMY (view in document) Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities. Volume 20. Issue 1 Article 3. The King and I: The Separation of Powers in Early Hebraic Political Theory. (view in document) The Crown and the Courts: Separation of Powers in the Early Jewish Imagination Biographies Moderator: Ethan J. Leib is Professor of Law at Fordham Law School. He teaches in contracts, legislation, and regulation. His most recent book, Friend v. Friend: Friendships and What, If Anything, the Law Should Do About Them, explores the costs and benefits of the legal recognition of and sensitivity to friendship; it was published by Oxford University Press. Leib’s scholarly articles have recently appeared in the Yale Law Journal, Virginia Law Review, Georgetown Law Journal, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, University of Chicago Law Review, California Law Review, and elsewhere. He has also written for a broader audience in the New York Times, USA Today, Policy Review, Washington Post, New York Law Journal, The American Scholar, and The New Republic. -

Hypocrites Or Pious Scholars? the Image of the Pharisees in Second Temple Period Texts and Rabbinic Literature

HYPOCRITES OR PIOUS SCHOLARS? THE IMAGE OF THE PHARISEES IN SECOND TEMPLE PERIOD TEXTS AND RABBINIC LITERATURE Etka Liebowitz* ABSTRACT: This article focuses upon Josephus’ portrayal of the Pharisees during the reign of Queen Alexandra, relating it to tHeir depiction in other contemporary sources (the New Testament, Qumran documents) as well as rabbinic literature. THe numerous Hostile descriptions of the PHarisees in botH War and Antiquities are examined based upon a pHilological, textual and source-critical analysis. Explanations are tHen offered for the puzzling negative description of tHe PHarisees in rabbinic literature (bSotah 22b), wHo are considered tHe predecessors of the sages. THe Hypocrisy cHarge against tHe PHarisees in Matthew 23 is analyzed from a religious-political perspective and allegorical references to the Pharisees as “Seekers of Smooth Things” in Pesher Nahum are also connected to the Hypocrisy motif. THis investigation leads to tHe conclusion tHat an anti-PHarisee bias is not unique to the New Testament but is also found in JewisH sources from tHe Second Temple period. It most probably reflects the rivalry among the various competing religious/political groups and tHeir struggle for dominance. Who were tHe PHarisees – a small religious sect, an influential political party, or a mass movement? Attempts to define and describe tHe pHenomenon of tHe PHarisees Have aroused considerable scholarly debate for decades.1 THis article will focus upon Josephus’ portrayal of tHe PHarisees during tHe reign of Queen Alexandra in The Judaean War and Judaean Antiquities and attempt to understand How it can sHed ligHt upon tHeir depiction in otHer Second Temple period texts – tHe New Testament (MattHew) and Qumran documents (Pesher Nahum), as well as in rabbinic literature (bSotah). -

Golden Bells and Pomegranates

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel and Peter Schäfer 94 ART I BUS Burton L. Visotzky Golden Bells and Pomegranates Studies in Midrash Leviticus Rabbah Mohr Siebeck Burton L. Visotzky, born 1951; Prof. Visotzky holds the Nathan and Janet Appleman Chair in Midrash and Interreligious Studies at the Jewish Theological Seminary, New York. ISBN 3-16-147991-2 ISSN 0721-8753 Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; de- tailed bibliographic data is available in the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2003 J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer in Tubingen using Times typeface, printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgements The preacher was quite right, there is no end to the making of books. This monograph on Midrash Leviticus Rabbah has been long in the making and I owe gratitude to many scholars who have commented on the work in progress over the years. I have benefited by being able to present my work on Leviticus Rabbah to my colleagues in a variety of academic fora over the years and I here express my thanks to the following: JTSA colleagues (2000, Faculty Lunch and Learn), Hebrew University (1999, Dinur Center and Ettinger Forum), SBL International (1998, Krakow), Ecole Biblique and Sorbonne (1998, Jerusalem Colloquy on Jewish-Christianity), SBL Annual Meeting (1982) Thanks also to those who have read and commented on various chapters of the work in a variety of forms: Profs. -

Ruah Ha-Kodesh in Rabbinic Literature

The Dissertation Committee for Julie Hilton Danan Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: THE DIVINE VOICE IN SCRIPTURE: RUAH HA-KODESH IN RABBINIC LITERATURE Committee: Harold A. Liebowitz , Supervisor Aaron Bar -Adon Esther L. Raizen Abraham Zilkha Krist en H. Lindbeck The Divine Voice in Scripture: Ruah ha-Kodesh in Rabbinic Literature by Julie Hilton Danan, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2009 Dedication To my husband, Avraham Raphael Danan Acknowledgements Thank you to the University of Texas at Austin Graduate School, the Middle Eastern Studies Department, and particularly to the Hebrew Studies faculty for their abundant support over my years of study in graduate school. I am especially grateful to the readers of my dissertation for many invaluable suggestions and many helpful critiques. My advisor, Professor Harold Liebowitz, has been my guide, my mentor, and my academic role model throughout the graduate school journey. He exemplifies the spirit of patience, thoughtful listening, and a true love of learning. Many thanks go to my readers, professors Esther Raizen, Avraham Zilkha, Aaron Bar-Adon, and Kristen Lindbeck (of Florida Atlantic University), each of whom has been my esteemed teacher and shared his or her special area of expertise with me. Thank you to Graduate Advisor Samer Ali and the staff of Middle Eastern Studies, especially Kimberly Dahl and Beverly Benham, for their encouragement and assistance. -

Dr. ROIE YELLINEK 1 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE

Dr. ROIE YELLINEK 25/10 Hanoch Albeck, Jerusalem, Israel, 9354839 [email protected], +972-54-7550122 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2020-today Ono Academic College Lecturer and Writing Clinic Director. 2019-today IDF Dado Center: Israel Military Think Tank, Tel-Aviv Adjunct Researcher Research Field: Strategic Aspects of the Chinese Involvement in the Middle East. 2018-today Middle East Institute (MEI), Washington D.C. Non-Resident Scholar Research Fields: Israel and the Palestinians, China - Middle East Relations. 2017-today China-MED Project, Torino Associate Researcher Research Field: The perception of China in the Israeli Media. 2015-today Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies (BESA), Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gan Research associate and China-Israel/MENA Forum director Research Fields: China-Middle East Relations. 2012-2014 The Institute for Zionist Strategies, Jerusalem Researcher Member of the Institute Journal and Legislation-Religion Research Teams. 2012-2013 The Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), Tel Aviv Research Assistant Research Fields: Security, Regional Dynamics and Processes in the Gulf States. 2010-2012 Department of Middle-Eastern Studies, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat- Gan Research Assistant Research Fields: Society and Tribalism in Saudi-Arabia. FELLOWSHIPS 2021 German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA) Visiting fellow / Postdoc Position 2017 Shanghai University, Shanghai Visiting Scholar Research Field: China - Israel Relations 2016-2018 Kohelet Policy Forum, Jerusalem Fellow Research Field: China - Israel Relations. EDUCATION 2016-2020 Ph.D., Bar-Ilan University, School of Communication and the Department of Middle Eastern Studies, Ramat-Gan (University President's Scholarship) Dissertation: Chinese Soft Power towards the Middle East and the Local Response to it. -

Hayyim Nahman Bialik - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Hayyim Nahman Bialik - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Hayyim Nahman Bialik(9 January 1873 – 4 July 1934) Hayim Nahman Bialik, also Chaim or Haim, was a Jewish poet who wrote primarily in Hebrew but also in Yiddish. Bialik was one of the pioneers of modern Hebrew poetry and came to be recognized as Israel's national poet. <b>Biography</b> Bialik was born in the village of Radi, Volhynia in the Ukrainian part of the Russian Empire to Yitzhak Yosef Bialik, a scholar and businessman, and his wife Dinah (Priveh). Bialik's father died in 1880, when Bialik was 7 years old. In his poems, Bialik romanticized the misery of his childhood, describing seven orphans left behind—though modern biographers believe there were fewer children, including grown step-siblings who did not need to be supported. Be that as it may, from the age 7 onwards Bialik was raised in Zhitomir (also Ukraine) by his stern Orthodox grandfather, Yaakov Moshe Bialik. In Zhitomir he received a traditional Jewish religious education, but also explored European literature. At the age of 15, inspired by an article he read, he convinced his grandfather to send him to the Volozhin Yeshiva in Lithuania, to study at a famous Talmudic academy under Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin, where he hoped he could continue his Jewish schooling while expanding his education to European literature as well. Attracted to the Jewish Enlightenment movement (Haskala), Bialik gradually drifted away from yeshiva life. Poems such as HaMatmid ("The Talmud student") written in 1898, reflect his great ambivalence toward that way of life: on the one hand admiration for the dedication and devotion of the yeshiva students to their studies, on the other hand a disdain for the narrowness of their world. -

Between Concealment and Revelatiotpwoon Mystical Motifs in Selected Yiddish Works of Isaac Bashevis Singer and Their Sources in Kabbalistic Literature

% % *EQ'8Tn4R Between Concealment and RevelatiotPwooN Mystical Motifs in Selected Yiddish Works of Isaac Bashevis Singer and Their Sources in Kabbalistic Literature Haike Beruriah Wiegand Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies University College London Degree: Ph.D. ProQuest Number: 10010417 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10010417 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract of Thesis Between Concealment and Revelation - Mystical Motifs in Selected Yiddish Works of Isaac Bashevis Singer and Their Sources in Kabbalistic Literature The subject of this study is an exploration of Jewish mystical motifs in the works of Yitskhok Bashevis Zinger (Isaac Bashevis Singer). The study is based on a close reading of the Yiddish original of all of Bashevis’s works investigated here. Changes or omissions in the English translations are mentioned and commented upon, wherever it is appropriate. This study consists of three major parts, apart from an introduction (Chapter 1) and a conclusion (Chapter 9). The first major part (Chapter 2) investigates the kabbalistic and hasidic influences on Bashevis’s life and the sources which inform the mystical aspects of his works.