By Anne S. Kreps a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020

Adult Sunday School Lesson Nassau Bay Baptist Church December 6, 2020 In this beginning of the Gospel According to Luke, we learn why Luke wrote this account and to whom it was written. Then we learn about the birth of John the Baptist and the experience of his parents, Zacharias and Elizabeth. Read Luke 1:1-4 Luke tells us that many have tried to write a narrative of Jesus’ redemptive life, called a gospel. Attached to these notes is a list of gospels written.1 The dates of these gospels span from ancient to modern, and this list only includes those about which we know or which have survived the millennia. Canon The Canon of Scripture is the list of books that have been received as the text that was inspired by the Holy Spirit and given to the church by God. The New Testament canon was not “closed” officially until about A.D. 400, but the churches already long had focused on books that are now included in our New Testament. Time has proven the value of the Canon. Only four gospels made it into the New Testament Canon, but as Luke tells us, many others were written. Twenty-seven books total were “canonized” and became “canonical” in the New Testament. In the Old Testament, thirty-nine books are included as canonical. Canonical Standards Generally, three standards were held up for inclusion in the Canon. • Apostolicity—Written by an Apostle or very close associate to an Apostle. Luke was a close associate of Paul. • Orthodoxy—Does not contradict previously revealed Scripture, such as the Old Testament. -

Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File

Intellectuals Displaced from Fascist Italy © Firenze University Press 2019 Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File «When, in 1938, I delivered my last lecture at this University, as a libero docente Link to other connected Lives on the [lecturer with official certification to teach at the university] of Hebrew language move: and literature I would not have believed...»: in this way, Elia Samuele Artom opened Emanuele Menachem the commemoration of his brother-in-law, Umberto Cassuto, on 28 May 1952 in Artom 1 Enzo Bonaventura Florence, where he was just passing through . Umberto Cassuto The change that so many lives, like his own, had to undergo as a result of anti- Anna Di Gioacchino Cassuto Jewish laws was radical. Artom embarked for Mandatory Palestine in September Enrico Fermi Kalman Friedman 1939, with his younger son Ruben. Upon arrival he found a land that was not simple, Dante Lattes whose ‘promise’ – at the center of the sources of tradition so dear to him – proved Alfonso Pacifici David Prato to be far more elusive than certain rhetoric would lead one to believe. Giulio Racah His youth and studies Elia Samuele Artom was born in Turin on 15 June 1887 to Emanuele Salvador (8 December 1840 – 17 June 1909), a post office worker from Asti, and Giuseppina Levi (27 August 1849 – 1 December 1924), a kindergarten teacher from Carmagnola2. He immediately showed a unique aptitude for learning: after being privately educated,3 he obtained «the high school honors diploma» in 1904; he graduated in literature «with full marks and honors» from the Facoltà di Filosofia e 1 Elia Samuele Artom, Umberto Cassuto, «La Rassegna mensile di Israel», 18, 1952, p. -

The Body/Soul Metaphor the Papal/Imperial Polemic On

THE BODY/SOUL METAPHOR THE PAPAL/IMPERIAL POLEMIC ON ELEVENTH CENTURY CHURCH REFORM by JAMES R. ROBERTS B.A., Catholic University of America, 1953 S.T.L., University of Sr. Thomas, Rome, 1957 J.C.B., Lateran University, Rome, 1961 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in » i THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1977 Co) James R. Roberts, 1977 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date Index Chapter Page (Abst*ac't 'i Chronological list of authors examined vii Chapter One: The Background . 1 Chapter Two: The Eleventh Century Setting 47 Conclusion 76 Appendices 79 A: Excursus on Priestly Dignity and Authority vs Royal or Imperial Power 80 B: Excursus: The Gregorians' Defense of the Church's Necessity for Corporal Goods 87 Footnotes 92 ii ABSTRACT An interest in exploring the roots of the Gregorian reform of the Church in the eleventh century led to the reading of the polemical writings by means of which papalists and imperialists contended in the latter decades of the century. -

The Apocryphal Gospels

A NOW YOU KNOW MEDIA W R I T T E N GUID E The Apocryphal Gospels: Exploring the Lost Books of the Bible by Fr. Bertrand Buby, S.M., S.T.D. LEARN WHILE LISTENING ANYTIME. ANYWHERE. THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS: EXPLORING THE LOST BOOKS OF THE BIBLE WRITTEN G U I D E Now You Know Media Copyright Notice: This document is protected by copyright law. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. You are permitted to view, copy, print and distribute this document (up to seven copies), subject to your agreement that: Your use of the information is for informational, personal and noncommercial purposes only. You will not modify the documents or graphics. You will not copy or distribute graphics separate from their accompanying text and you will not quote materials out of their context. You agree that Now You Know Media may revoke this permission at any time and you shall immediately stop your activities related to this permission upon notice from Now You Know Media. WWW.NOWYOUKNOWMEDIA.COM / 1 - 800- 955- 3904 / © 2010 2 THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS: EXPLORING THE LOST BOOKS OF THE BIBLE WRITTEN G U I D E Table of Contents Topic 1: An Introduction to the Apocryphal Gospels ...................................................7 Topic 2: The Protogospel of James (Protoevangelium of Jacobi)...............................10 Topic 3: The Sayings Gospel of Didymus Judas Thomas...........................................13 Topic 4: Apocryphal Infancy Gospels of Pseudo-Thomas and Others .......................16 Topic 5: Jewish Christian Apocryphal Gospels ..........................................................19 -

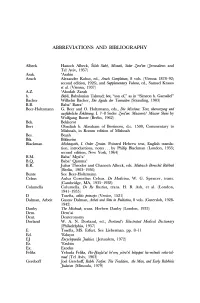

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

Download Ancient Apocryphal Gospels

MARKus BOcKMuEhL Ancient Apocryphal Gospels Interpretation Resources for the Use of Scripture in the Church BrockMuehl_Pages.indd 3 11/11/16 9:39 AM © 2017 Markus Bockmuehl First edition Published by Westminster John Knox Press Louisville, Kentucky 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26—10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information, address Westminster John Knox Press, 100 Witherspoon Street, Louisville, Kentucky 40202- 1396. Or contact us online at www.wjkbooks.com. Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. and are used by permission. Map of Oxyrhynchus is printed with permission by Biblical Archaeology Review. Book design by Drew Stevens Cover design by designpointinc.com Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Bockmuehl, Markus N. A., author. Title: Ancient apocryphal gospels / Markus Bockmuehl. Description: Louisville, KY : Westminster John Knox Press, 2017. | Series: Interpretation: resources for the use of scripture in the church | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016032962 (print) | LCCN 2016044809 (ebook) | ISBN 9780664235895 (hbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781611646801 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal Gospels—Criticism, interpretation, etc. | Apocryphal books (New Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS2851 .B63 2017 (print) | LCC BS2851 (ebook) | DDC 229/.8—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016032962 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48- 1992. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

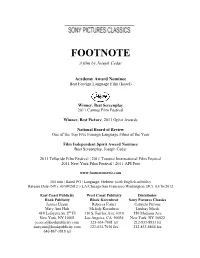

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

The Gnostic Religion 1940 Joined the British Army in the Middle East

THE MESSAGE OF THE ALIEN GOD & THE BEGINNINGS OF CHRISTIANITY Hans Jonas (1903-1993) was born and educated in Germany, where he was a pupil of Martin Heidegger and Rudolf Bult- mann. He left in 1933, when Hitler came into power, and in The Gnostic Religion 1940 joined the British Army in the Middle East. After the war he taught at Hebrew University in Jerusalem and Carleton Uni- versity in Ottawa, finally settling in the United States. He was the Alvin Johnson Professor of Philosophy on the Graduate Fac- HANS JONAS ulty of Political and Social Science at the New School for Social Research in New York. Professor Jonas was also author of, among other books, The Phenomenon of Life (1966). He died in 1993- THIRD EDITION BEACON PRESS BOSTON Beacon Press For Lore Jonas 25 Beacon Street Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892 www.beacon.org Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations. © 1958, 1963, 1991, 2001 by Hans Jonas All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 05 04 03 02 01 00 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jonas, Hans The gnostic religion : the message of the alien God and the beginnings of Christianity / Hans Jonas.—3rd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8070-5801-7 (pbk.) I. Gnosticism I. Title BT1390 J62 2001 00-060852 273'.1— dc21 Scanned: February 2005 Contents Preface to the Third Edition xiii Note on the Occasion of the Third Printing (1970) xxx Preface to the Second Edition xxvi Preface to the First Edition xxxi Abbreviations xxxiii 1. -

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WOMEN's IDENTITY and RELIGION in the ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN Virginia K.R

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Masters Essays Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects Spring 2015 FLESH AND BLOOD: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WOMEN'S IDENTITY AND RELIGION IN THE ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN Virginia K.R. Phillips [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Phillips, Virginia K.R., "FLESH AND BLOOD: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WOMEN'S IDENTITY AND RELIGION IN THE ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN" (2015). Masters Essays. 18. http://collected.jcu.edu/mastersessays/18 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Essays, and Senior Honors Projects at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Essays by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLESH AND BLOOD: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN WOMEN'S IDENTITY AND RELIGION IN THE ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN. An Essay Submitted to The Graduate School of John Carroll University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Virginia K.R. Phillips 2015 Introduction Women's roles in religion have been a topic of some interest over the past few years, with much scholarship and argumentation surrounding theological ideas and historical realities. This paper does not seek to add new material to the understanding of what women's religious roles were in the ancient Mediterranean, but rather to look at those roles and other religious proscriptions and examine how women -

Morgenstern Is a Senior Fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem

Dispersion and the Longing for Zion, 1240-1840 rie orgenstern t has become increasingly accepted in recent years that Zionism is a I strictly modern nationalist movement, born just over a century ago, with the revolutionary aim of restoring Jewish sovereignty in the land of Israel. And indeed, Zionism was revolutionary in many ways: It rebelled against a tradition that in large part accepted the exile, and it attempted to bring to the Jewish people some of the nationalist ideas that were animat- ing European civilization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centu- ries. But Zionist leaders always stressed that their movement had deep historical roots, and that it drew its vitality from forces that had shaped the Jewish consciousness over thousands of years. One such force was the Jewish faith in a national redemption—the belief that the Jews would ultimately return to the homeland from which they had been uprooted. This tension, between the modern and the traditional aspects of Zion- ism, has given rise to a contentious debate among scholars in Israel and elsewhere over the question of how the Zionist movement should be described. Was it basically a modern phenomenon, an imitation of the winter 5762 / 2002 • 71 other nationalist movements of nineteenth-century Europe? If so, then its continuous reference to the traditional roots of Jewish nationalism was in reality a kind of facade, a bid to create an “imaginary community” by selling a revisionist collective memory as if it had been part of the Jewish historical consciousness all along. Or is it possible to accept the claim of the early Zionists, that at the heart of their movement stood far more ancient hopes—and that what ultimately drove the most remarkable na- tional revival of modernity was an age-old messianic dream? For many years, it was the latter belief that prevailed among historians of Zionism. -

Copyright by Harold Glenn Revelson 2005

Copyright by Harold Glenn Revelson 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Harold Glenn Revelson certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ONTOLOGICAL TORAH: AN INSTRUMENT OF RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL DISCOURSE Committee: ______________________________________ Aaron Bar-Adon, Supervisor ______________________________________ Abraham Marcus ______________________________________ Yair Mazor ______________________________________ Adam Zachary Newton ______________________________________ Esther Raizen ONTOLOGICAL TORAH: AN INSTRUMENT OF RELIGIOUS AND SOCIAL DISCOURSE by Harold Glenn Revelson, B.S., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2005 With affection to my professors and my dear friends on Shihrur St., Maoz Tzion, Israel Acknowledgements The number of people to whom I owe thanks for their support and help during my academic journey is so large that I could not possibly mention each of them individually. They were equally as important to any success that might have been achieved along the way as those named below. I appreciate all of them greatly. I wish to express thanks to my professors in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. I shall never be able to quantify the invaluable contributions that my adviser, Dr. Aaron Bar-Adon, has made to my academic and personal enrichment. From the day that I met him in July 1991, he has served as an exemplary scholar and teacher. Before the academic year of 1991-1992 began, he invited me to his office for weekly readings in Tanakh, and I have continued to glean from his storehouse of knowledge until today. -

Jewish Apocryphon, Known from Various Patristic Sources.I7 The

JEWISH SOtJRC‘t:S IN GNOS’I I(‘ t,t’t’ERA’t URE JEWISH SOURC‘ES IN GNOSTIC‘ LITERATURE I Jewish apocryphon, known from various patristic sources.i7 The same apocryphon under that name now extant in Slavonic.26 It is more likely, group used a ‘Gospel of Eve’ and ‘many books in the name of Seth’ (Haer. however, that the Sethian Apocalypse of Abraham was a Gnostic work, in 26:8, 1). The latter would certainly have included strictly Gnostic material view of the very interesting (though late) information supplied by (‘Ialdabaoth’ is mentioned in connection with them, ibid.) and a number of Theodore Bar Konai (8th century) regarding the Audians, a Gnostic sect books in the name of Seth are now to be found in the Nag Hammadi which seems to have been closely related to the Sethian Gnostics, and who Corpus.l8 Non-Gnostic Jewish books in the name of Seth also circulated in used ‘an apocalypse under the name of Abraham’. This apocryphal work, late antiquity, lg though we have no way of knowing whether such were in typically Gnostic fashion, attributed the creation of the world to ‘Dark- included in the Nicolaitan library. 2o A book of ‘Noria’ is said to have been ness’ and six other ‘powers’.27 used among these same Gnostics (Haer. 26: 1,4-9), consisting of a fanciful The church father Hippolytus does not provide much information of use retelling of the story of Noah’s ark, ‘Noria’ in this instance being Noah’s to us in the present connection, but his notices about the Paraphrase of Seth wife.21 (Ref 5: 19, l-22, 1) in use among the Sethian Gnostics should be mentioned Epiphanius records that books in the name of Seth and Allogenes (= here, as well as his discussion of the Gnostic book entitled Buruch (Ref: Seth) were in use among the Sethians and the closely-related Archontics 5:26, l-27, 5).