Golden Bells and Pomegranates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ten Makkos: Middah K'neged Middah According to the Midrash

D_18365 Ten Makkos: Middah K’neged Middah According to the Midrash By Mr. Robert Sussman Grade Level: Elementary, Middle School, High School, Adult Description: Explanations, based on various midrashim, that display how each of the ten makkos were meted out to the Mitzrim middah k’neged middah. Additional interesting information about each makkah is included in the “Did You Know” sections. Use these professionally designed sheets when preparing to teach the makkos or distribute to students as a supplement to their haggados. Includes a source for each explanation. Instructions: 1. Read through the explanations. 2. Explain the concept of middah k’neged middah, if students are not already familiar with it. 3. Encourage students to figure out how each Makkah was middah k’neged middah. 4. Teach the explanations provided by the Midrash. 5. OPTIONAL: Distribute these sheets to your students. Haggadah Insights Shock and AWE Who doesn’t know the Ten Plagues? Hashem, who is All Powerful, could have done anything to the Egyptians that He wanted, so why did He choose those ten a# ictions? e Midrash teaches that Hashem brought the plagues middah keneged middah (measure for measure). In other words, each one of the plagues was to punish the Egyptians for something they had done to persecute the Children of Israel I BY ROBERT SUSSMAN the ! sh that died in the Nile and the KINIM !LICE" # WHY? stench that was in the air. And a proof of 3 e Egyptians would make the Chil- this is that we see that Pharaoh’s magi- dren of Israel sweep their houses, their cians were able to turn the Nile to blood – streets, and their markets, therefore if it hadn’t returned to its prior state of Hashem changed all of the dust in Egypt being water, how would they have been into lice until there was no more dust to able to do so?! (Chizkuni) sweep. -

Hermeneutics As Poetics: the Case of Midrash Hagadol

Abstract Hermeneutics as Poetics: The Case of Midrash HaGadol Gilad Shapira One of the fascinating characteristics of Midrash is its dual nature as both poetic and hermeneutic. Late Midrash has been shown to accentuate the literary, rather than the exegetical dimension of given genres (e.g. the Mashal, the retold biblical narrative). This paper addresses the place of hermeneutics in a seminal work of Late Midrash – Midrash HaGadol (Aden, Yemen, 14th century): This discussion is centered on the hermeneutical expression, ‘zehu sheamar hakatuv’ (this is what Scripture said) and the way it functions to create bundles of textual units around thematic focuses, and it indicates their components. Based on that, the paper argues that the function of hermeneutics in Midrash Hagadol is primarily poetic. [Jerusalem Studies in Hebrew Literature, XXXI (2020), pp. 1-25] Abstract The Road to Lydda: A Survivor’s Story Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai’s Flight from Jerusalem According to Eicha Rabba 1:5 Moshe Shoshan This article presents an analysis of the story of the escape of R. Yohanan ben Zakkai from Jerusalem as it appears in Eicha Rabba. This version of the story differs markedly from the accounts found elsewhere in rabbinic literature, most notably in that it does not refer to R. Yohanan’s request to save ‘Yavne and her sages’. The Eicha Rabba account focuses on the survival of the Jews rather than on the establishment of a center of Jewish study and practice to succeed Jerusalem. Torah is presented as a source of practical wisdom, which gives the rabbis the ability to save a remnant of their people. -

Rosh Hashana 5780: There Must Have Been Tears Rabbanit Leah Sarna

Rosh Hashana 5780: There Must Have Been Tears Rabbanit Leah Sarna When is the last time you cried? Think back to it. This is an easy exercise for me since I cry all the time-- but for you it might not be. Was it recently? Was it yesterday? Was it years ago? Were you watching a movie? Reading the news? Tears of joy? Tears of sorrow? Frustration? Tears of truth-telling? Tears of empathy? Think back to it. In Great Expectations, Charles Dickens puts into the words of Pip, the main character and narrator, one of my favorite quotes about tears, just as he leaves his sister’s house and his apprenticeship and goes off to London to become a gentleman: “Heaven knows we need never be ashamed of our tears, for they are rain upon the blinding dust of earth, overlying our hard hearts. I was better after I had cried, than before--more sorry, more aware of my own ingratitude, more gentle.” Rain upon the blinding dust of earth, overlying our hard hearts. Tears open our hearts. It’s not always that feelings give way to tears, says Dickens-- often it’s the other way around, tears alert us to feelings, soften us, make us more sorry, more gentle, more whatever it is that we were feeling before --but unable to access. (PART I.) In today’s Haftara we have the tears of Rachel, crying for her exiled children. In yesterday’s Torah and Haftara readings, we encountered a whole lot of tears: the tears of Hagar, the tears of Ishmael, and the tears of Hannah. -

Feminist Sexual Ethics Project

Feminist Sexual Ethics Project Same-Sex Marriage Gail Labovitz Senior Research Analyst, Feminist Sexual Ethics Project There are several rabbinic passages which take up, or very likely take up, the subject of same-sex marital unions – always negatively. In each case, homosexual marriage (particularly male homosexual marriage) is rhetorically stigmatized as the practice of non-Jewish (or pre-Israelite) societies, and is presented as an outstanding marker of the depravity of those societies; homosexual marriage is thus clearly associated with the Other. The first three of the four rabbinic texts presented here also associate homosexual marriage with bestiality. These texts also employ a rhetoric of fear: societal recognition of such homosexual relationships will bring upon that society extreme forms of Divine punishment – the destruction of the generation of the Flood, the utter defeat of the Egyptians at the Exodus, the wiping out of native Canaanite peoples in favor of the Israelites. The earliest source on this topic is in the tannaitic midrash to the book of Leviticus. Like a number of passages in Leviticus, including chapter 18 to which it is a commentary, the midrashic passage links sexual sin and idolatry to the Egyptians (whom the Israelites defeated in the Exodus) and the Canaanites (whom the Israelites will displace when they come into their land). The idea that among the sins of these peoples was the recognition of same-sex marriages is not found in the biblical text, but is read in by the rabbis: Sifra Acharei Mot, parashah 9:8 “According to the doings of the Land of Egypt…and the doings of the Land of Canaan…you shall not do” (Leviticus 18:3): Can it be (that it means) don’t build buildings, and don’t plant plantings? Thus it (the verse) teaches (further), “And you shall not walk in their statutes.” I say (that the prohibition of the verse applies) only to (their) statutes – the statutes which are theirs and their fathers and their fathers’ fathers. -

The Relationship Between Targum Song of Songs and Midrash Rabbah Song of Songs

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TARGUM SONG OF SONGS AND MIDRASH RABBAH SONG OF SONGS Volume I of II A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 PENELOPE ROBIN JUNKERMANN SCHOOL OF ARTS, HISTORIES, AND CULTURES TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME ONE TITLE PAGE ............................................................................................................ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. 2 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................. 6 DECLARATION ........................................................................................................ 7 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DEDICATION ............................................................... 9 CHAPTER ONE : INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 11 1.1 The Research Question: Targum Song and Song Rabbah ......................... 11 1.2 The Traditional View of the Relationship of Targum and Midrash ........... 11 1.2.1 Targum Depends on Midrash .............................................................. 11 1.2.2 Reasons for Postulating Dependency .................................................. 14 1.2.2.1 Ambivalence of Rabbinic Sources Towards Bible Translation .... 14 1.2.2.2 The Traditional -

Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File

Intellectuals Displaced from Fascist Italy © Firenze University Press 2019 Elia Samuele Artom Go to Personal File «When, in 1938, I delivered my last lecture at this University, as a libero docente Link to other connected Lives on the [lecturer with official certification to teach at the university] of Hebrew language move: and literature I would not have believed...»: in this way, Elia Samuele Artom opened Emanuele Menachem the commemoration of his brother-in-law, Umberto Cassuto, on 28 May 1952 in Artom 1 Enzo Bonaventura Florence, where he was just passing through . Umberto Cassuto The change that so many lives, like his own, had to undergo as a result of anti- Anna Di Gioacchino Cassuto Jewish laws was radical. Artom embarked for Mandatory Palestine in September Enrico Fermi Kalman Friedman 1939, with his younger son Ruben. Upon arrival he found a land that was not simple, Dante Lattes whose ‘promise’ – at the center of the sources of tradition so dear to him – proved Alfonso Pacifici David Prato to be far more elusive than certain rhetoric would lead one to believe. Giulio Racah His youth and studies Elia Samuele Artom was born in Turin on 15 June 1887 to Emanuele Salvador (8 December 1840 – 17 June 1909), a post office worker from Asti, and Giuseppina Levi (27 August 1849 – 1 December 1924), a kindergarten teacher from Carmagnola2. He immediately showed a unique aptitude for learning: after being privately educated,3 he obtained «the high school honors diploma» in 1904; he graduated in literature «with full marks and honors» from the Facoltà di Filosofia e 1 Elia Samuele Artom, Umberto Cassuto, «La Rassegna mensile di Israel», 18, 1952, p. -

The Anti-Samaritan Attitude As Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim

religions Article The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim Andreas Lehnardt Faculty of Protestant Theology, Johannes Gutenberg‑University Mainz, 55122 Mainz, Germany; lehnardt@uni‑mainz.de Abstract: Samaritans, as a group within the ranges of ancient ‘Judaisms’, are often mentioned in Talmud and Midrash. As comparable social–religious entities, they are regarded ambivalently by the rabbis. First, they were viewed as Jews, but from the end of the Tannaitic times, and especially after the Bar Kokhba revolt, they were perceived as non‑Jews, not reliable about different fields of Halakhic concern. Rabbinic writings reflect on this change in attitude and describe a long ongoing conflict and a growing anti‑Samaritan attitude. This article analyzes several dialogues betweenrab‑ bis and Samaritans transmitted in the Midrash on the book of Genesis, Bereshit Rabbah. In four larger sections, the famous Rabbi Me’ir is depicted as the counterpart of certain Samaritans. The analyses of these discussions try to show how rabbinic texts avoid any direct exegetical dispute over particular verses of the Torah, but point to other hermeneutical levels of discourse and the rejection of Samari‑ tan claims. These texts thus reflect a remarkable understanding of some Samaritan convictions, and they demonstrate how rabbis denounced Samaritanism and refuted their counterparts. The Rabbi Me’ir dialogues thus are an impressive literary witness to the final stages of the parting of ways of these diverging religious streams. Keywords: Samaritans; ancient Judaism; rabbinic literature; Talmud; Midrash Citation: Lehnardt, Andreas. 2021. The Anti‑Samaritan Attitude as 1 Reflected in Rabbinic Midrashim. The attitudes towards the Samaritans (or Kutim ) documented in rabbinical literature 2 Religions 12: 584. -

Is There an Authentic Triennial Cycle of Torah Readings? RABBI LIONEL E

Is there an Authentic Triennial Cycle of Torah Readings? RABBI LIONEL E. MOSES This paper is an appendix to the paper "Annual and Triennial Systems For Reading The Torah" by Rabbi Elliot Dorff, and was approved together with it on April 29, 1987 by a vote of seven in favor, four opposed, and two abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Isidoro Aizenberg, Ben Zion Bergman, Elliot N. Dorff, Richard L. Eisenberg, Mayer E. Rabinowitz, Seymour Siegel and Gordon Tucker. Members voting in opposition: Rabbis David H. Lincoln, Lionel E. Moses, Joel Roth and Steven Saltzman. Members abstaining: Rabbis David M. Feldman and George Pollak. Abstract In light of questions addressed to the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards from as early as 1961 and the preliminary answers given to these queries by the committee (Section I), this paper endeavors to review the sources (Section II), both talmudic and post-talmudic (Section Ila) and manuscript lists of sedarim (Section lib) to set the triennial cycle in its historical perspective. Section III of the paper establishes a list of seven halakhic parameters, based on Mishnah and Tosefta,for the reading of the Torah. The parameters are limited to these two authentically Palestinian sources because all data for a triennial cycle is Palestinian in origin and predates even the earliest post-Geonic law codices. It would thus be unfair, to say nothing of impossible, to try to fit a Palestinian triennial reading cycle to halakhic parameters which were both later in origin and developed outside its geographical sphere of influence. Finally in Section IV, six questions are asked regarding the institution of a triennial cycle in our day and in a short postscript, several desiderata are listed in order to put such a cycle into practice today. -

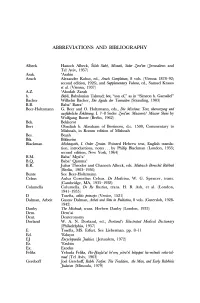

Abbreviations and Bibliography

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY Albeck Hanoch Albeck, Sifah Sidre, Misnah, Seder Zera'im (Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, 1957) Arak. 'Arakin Aruch Alexander Kohut, ed., Aruch Completum, 8 vols. (Vienna 1878-92; second edition, 1926), and Supplementary Volume, ed., Samuel Krauss et al. (Vienna, 193 7) A.Z. 'Abodah Zarah b. Babli, Babylonian Talmud; ben, "son of," as in "Simeon b. Gamaliel" Bacher Wilhelm Bacher, Die Agada der Tannaiten (Strassling, 1903) B.B. Baba' Batra' Beer-Holtzmann G. Beer and 0. Holtzmann, eds., Die Mischna: Text, iiberset::;ung und ausfiihrliche Erkliirung, I. 7-8 Seder Zera'im: Maaserotl Mauser Sheni by Wolfgang Bunte (Berlin, 1962) Bek. Bekhorot Bert Obadiah b. Abraham of Bertinoro, d.c. 1500, Commentary to Mishnah, in Romm edition of Mishnah Bes. Be~ah Bik. Bikkurim Blackman Mishnayoth, I. Order Zeraim. Pointed Hebrew text, English transla tion, introductions, notes ... by Philip Blackman (London, 1955; second edition, New York, 1964) B.M. Baba' Mesi'a' B.Q Baba' Qamma' B.R. Julius Theodor and Chanoch Albeck, eds. Midrasch Bereschit Rabbah (Berlin, 1903-1936) Bunte See Beer-Holtzmann Celsus Aulus Cornelius Celsus. De Medicina, W. G. Spencer, trans. (Cambridge, MA, 1935-1938) Columella Columella. De Re Rustica, trans. H. B. Ash, et al. (London, 1941-1955) D Tosefta, editio princeps (Venice, 1521) Dalman, Arbeit Gustav Dalman, Arbeit und Sitte in Paliistina, 8 vols. (Gutersloh, 1928- 1942) Danby The Mishnah, trans. Herbert Danby (London, 1933) Dem. Dem'ai Deut. Deuteronomy Dorland W. A. N. Dorland, ed., Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary (Philadelphia, 195 7) E Tosefta, MS. Erfurt. See Lieberman. pp. 8-11 Ed. -

JCYF Text Collection

Jewish Community Youth Foundation TEXTS: Draft Aug 24, 2007 Contents: 1. General Texts about Giving a. Not Teaching Your Children to Earn is to Teach them to Rob b. Tzedakah is Equivalent to all other Mitzvot c. Giving Will Not Make You Poor 2. We Don’t Really Own What We Give Away Anyway a. The Sabbatical Year b. Do Not Reap the Corners of your Land 3. Should the Poor Also Give? Two Perspectives a. Even Those Who Receive Tzedakah Should Give b. One’s Own Sustenance Comes First 4. Types of Giving a. Eight Categories of Giving Tzedakah, a.k.a Maimonides Ladder b. The Difference Between Tzedkah and Gemilut Hasadim c. Emergency Versus Ongoing Needs 5. Who Should We Give to? Texts about Allocating a. Allocating is Painful b. Give to Family First, then to the Neighbors c. Giving to Non-Jews d. How to Compare the Poor in your town to the Poor around the World 6. How Much Should We Give? a. Sufficient for his Needs (Day Machsoro) b. Defining ‘Sufficient for his Needs’ c. How Much to Give: 20%? 10%? 7. Tzedakah Midrash a. Midrash of the Sheep Crossing the River b. God Stands at the Right Side of a Poor Person 1. General Texts about Giving Not Teaching Your Children to Earn is to Teach them to Rob T. Kiddushin 29a Anyone who does not teach their child a skill or profession may be regarded as teaching their child to rob. Discussion: Do you think your parents have a responsibility to teach you a skill or profession? How does this teaching change your understanding of people who steal things? Tzedakah is Equivalent to all other Mitzvot B. -

Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew

Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures Heijmans Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew Shai Heijmans (ed.) EDITED BY SHAI HEIJMANS This volume presents a collec� on of ar� cles centring on the language of the Mishnah and the Talmud — the most important Jewish texts (a� er the Bible), which were compiled in Pales� ne and Babylonia in the la� er centuries of Late An� quity. Despite the fact that Rabbinic Hebrew has been the subject of growing academic interest across the past Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew century, very li� le scholarship has been wri� en on it in English. Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew addresses this lacuna, with eight lucid but technically rigorous ar� cles wri� en in English by a range of experienced scholars, focusing on various aspects of Rabbinic Hebrew: its phonology, morphology, syntax, pragma� cs and lexicon. This volume is essen� al reading for students and scholars of Rabbinic studies alike, and appears in a new series, Studies in Semi� c Languages and Cultures, in collabora� on with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. Printed and digital edi� ons, together with supplementary digital material, can also be found here: www.openbookpublishers.com Cover image: A fragment from the Cairo Genizah, containing Mishnah Shabbat 9:7-11:2 with Babylonian vocalisati on (Cambridge University Library, T-S E1.47). Courtesy of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Cover design: Luca Baff a book 2 ebooke and OA edi� ons also available OPEN ACCESS OBP STUDIES IN RABBINIC HEBREW Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew Edited by Shai Heijmans https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2020 Shai Heijmans. -

Why Was the Tabernacle So Important? (Vayak-Hel)

Sat 5 Mar 2016 – 25 Adar I 5776 B”H Dr Maurice M. Mizrahi Congregation Adat Reyim D’var Torah on Vayak-hel Why was the Tabernacle so important? This week's Torah portion, Vayak-hel, continues the long instructions for the building of the Tabernacle. The Tabernacle, or portable sanctuary, or Mishkan in Hebrew, containing the Ark of the Covenant, is the prototype of the future Temple, or Bet ha-Mikdash. God gives very detailed instructions on how to build it, stretching over many Torah portions, beginning with Parshat Terumah. One wonders: Why was the Tabernacle so important that it had to be built just so? Why so many verses devoted to it compared with other mitzvot? Let us begin with some examples of its perceived importance: -The Talmud, the Midrash, and the Zohar all say that the Mishkan came before the creation of the world. The Talmud says: It was taught: The following seven things were created before the world: The Torah, repentance, the Garden of Eden, Gehennom, the Throne of Glory, the Temple and the name of the Messiah [Pesachim 54a, also Gen. R. 1:4, Zohar, Tzav 34b]. This means that these things are at the very foundation of the world. -The Book of Samuel tells us that when the Philistines captured the Mishkan, the Israelites were thrown in despair. So much so that ‘Eli, a prominent judge and High Priest, and his pregnant daughter-in-law both died from the shock. [1Samuel 4]. -The number of lines in the Torah devoted to the Mishkan is far greater than the number of lines devoted to the creation of the world! A commentator has said that the reason is that it is easy for God to make a place for people to dwell in, but more difficult for people to make a place for God to dwell in.