Ruah Ha-Kodesh in Rabbinic Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jewish Intertestamental and Early Rabbinic Literature: an Annotated Bibliographic Resource Updated Again (Part 2)

JETS 63.4 (2020): 789–843 JEWISH INTERTESTAMENTAL AND EARLY RABBINIC LITERATURE: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHIC RESOURCE UPDATED AGAIN (PART 2) DAVID W. CHAPMAN AND ANDREAS J. KÖSTENBERGER* Part 1 of this annotated bibliography appeared in the previous issue of JETS (see that issue for an introduction to this resource). This again is the overall struc- ture: Part 1: 1. General Reference Tools; 2. Old Testament Versions; 3. Apocrypha; 4. Pseudepigrapha; Part 2: 5. Dead Sea Scrolls; 6. Individual Authors (Philo, Jose- phus, Pseudo-Philo, Fragmentary Works); 7. Rabbinic Literature; 8. Other Early Works from the Rabbinic Period; 9. Addenda to Part 1. 5. DEAD SEA SCROLLS While the Dead Sea Scrolls are generally associated with Qumran, properly they also cover discoveries from approximately a dozen other sites in the desert wilderness surrounding the Dead Sea, such as those at Naal ever, Murabbaat, and Masada. The approximately 930 MSS from Qumran were penned from the 3rd c. BC through the 1st c. AD. The Masada texts include Jewish scrolls from the time leading up to the Roman conquest (AD 73) and subsequent Roman documents. The finds at Naal ever and Murabbaat include documents from the time of the Bar Kokhba revolt (AD 132–135). Other Bar Kokhba era documents are known from Ketef Jericho, Wadi Sdeir, Naal Mishmar, and Naal eelim (see DJD 38). For a full accounting, see the lists by Tov under “Bibliography” below. The non- literary documentary papyri (e.g. wills, deeds of sale, marriage documents, etc.) are not covered below. Recent archaeological efforts seeking further scrolls from sur- rounding caves (esp. -

1 Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos

Jews, Gentiles, and the Modern Egalitarian Ethos: Some Tentative Thoughts David Berger The deep and systemic tension between contemporary egalitarianism and many authoritative Jewish texts about gentiles takes varying forms. Most Orthodox Jews remain untroubled by some aspects of this tension, understanding that Judaism’s affirmation of chosenness and hierarchy can inspire and ennoble without denigrating others. In other instances, affirmations of metaphysical differences between Jews and gentiles can take a form that makes many of us uncomfortable, but we have the legitimate option of regarding them as non-authoritative. Finally and most disturbing, there are positions affirmed by standard halakhic sources from the Talmud to the Shulhan Arukh that apparently stand in stark contrast to values taken for granted in the modern West and taught in other sections of the Torah itself. Let me begin with a few brief observations about the first two categories and proceed to somewhat more extended ruminations about the third. Critics ranging from medieval Christians to Mordecai Kaplan have directed withering fire at the doctrine of the chosenness of Israel. Nonetheless, if we examine an overarching pattern in the earliest chapters of the Torah, we discover, I believe, that this choice emerges in a universalist context. The famous statement in the Mishnah (Sanhedrin 4:5) that Adam was created singly so that no one would be able to say, “My father is greater than yours” underscores the universality of the original divine intent. While we can never know the purpose of creation, one plausible objective in light of the narrative in Genesis is the opportunity to actualize the values of justice and lovingkindness through the behavior of creatures who subordinate themselves to the will 1 of God. -

Conversion to Judaism Finnish Gerim on Giyur and Jewishness

Conversion to Judaism Finnish gerim on giyur and Jewishness Kira Zaitsev Syventävien opintojen tutkielma Afrikan ja Lähi-idän kielet Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto 2019/5779 provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk CORE brought to you by Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Kielten maisteriohjelma Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Afrikan ja Lähi-idän kielet Tekijä – Författare – Author Kira Zaitsev Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Conversion to Judaism. Finnish gerim on giyur and Jewishness Työn laji – Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal Arbetets art – Huhtikuu 2019 – Number of pages Level 43 Pro gradu Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Pro graduni käsittelee suomalaisia, jotka ovat kääntyneet juutalaisiksi ilman aikaisempaa juutalaista taustaa ja perhettä. Data perustuu haastatteluihin, joita arvioin straussilaisella grounded theory-menetelmällä. Tutkimuskysymykseni ovat, kuinka nämä käännynnäiset näkevät mitä juutalaisuus on ja kuinka he arvioivat omaa kääntymistään. Tutkimuseni mukaan kääntyjän aikaisempi uskonnollinen tausta on varsin todennäköisesti epätavallinen, eikä hänellä ole merkittäviä aikaisempia juutalaisia sosiaalisia suhteita. Internetillä on kasvava rooli kääntyjän tiedonhaussa ja verkostoissa. Juutalaisuudessa kääntynyt näkee tärkeimpänä eettisyyden sekä juutalaisen lain, halakhan. Kääntymisen nähdään vahvistavan aikaisempi maailmankuva -

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿavoda Zara By

The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara By Mira Beth Wasserman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley in Jewish Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Kenneth Bamberger Spring 2014 Abstract The Humanity of the Talmud: Reading for Ethics in Bavli ʿAvoda Zara by Mira Beth Wasserman Joint Doctor of Philosophy with Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Boyarin, chair In this dissertation, I argue that there is an ethical dimension to the Babylonian Talmud, and that literary analysis is the approach best suited to uncover it. Paying special attention to the discursive forms of the Talmud, I show how juxtapositions of narrative and legal dialectics cooperate in generating the Talmud's distinctive ethics, which I characterize as an attentiveness to the “exceptional particulars” of life. To demonstrate the features and rewards of a literary approach, I offer a sustained reading of a single tractate from the Babylonian Talmud, ʿAvoda Zara (AZ). AZ and other talmudic discussions about non-Jews offer a rich resource for considerations of ethics because they are centrally concerned with constituting social relationships and with examining aspects of human experience that exceed the domain of Jewish law. AZ investigates what distinguishes Jews from non-Jews, what Jews and non- Jews share in common, and what it means to be a human being. I read AZ as a cohesive literary work unified by the overarching project of examining the place of humanity in the cosmos. -

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract Julius Theodor (1849–1923)

By Tamar Kadari* Abstract This article is a biography of the prominent scholar of Aggadic literature, Rabbi Dr Julius Theodor (1849–1923). It describes Theodor’s childhood and family and his formative years spent studying at the Breslau Rabbinical Seminary. It explores the thirty one years he served as a rabbi in the town of Bojanowo, and his final years in Berlin. The article highlights The- odor’s research and includes a list of his publications. Specifically, it focuses on his monumental, pioneering work preparing a critical edition of Bereshit Rabbah (completed by Chanoch Albeck), a project which has left a deep imprint on Aggadic research to this day. Der folgende Artikel beinhaltet eine Biographie des bedeutenden Erforschers der aggadischen Literatur Rabbiner Dr. Julius Theodor (1849–1923). Er beschreibt Theodors Kindheit und Familie und die ihn prägenden Jahre des Studiums am Breslauer Rabbinerseminar. Er schil- dert die einunddreissig Jahre, die er als Rabbiner in der Stadt Bojanowo wirkte, und seine letzten Jahre in Berlin. Besonders eingegangen wird auf Theodors Forschungsleistung, die nicht zuletzt an der angefügten Liste seiner Veröffentlichungen ablesbar ist. Im Mittelpunkt steht dabei seine präzedenzlose monumentale kritische Edition des Midrasch Bereshit Rabbah (die Chanoch Albeck weitergeführt und abgeschlossen hat), ein Werk, das in der Erforschung aggadischer Literatur bis heute nachwirkende Spuren hinterlassen hat. Julius Theodor (1849–1923) is one of the leading experts of the Aggadic literature. His major work, a scholarly edition of the Midrash Bereshit Rabbah (BerR), completed by Chanoch Albeck (1890–1972), is a milestone and foundation of Jewish studies research. His important articles deal with key topics still relevant to Midrashic research even today. -

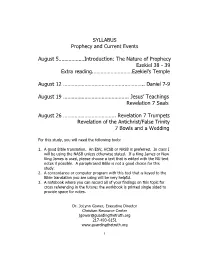

Prophecy and Current Events

SYLLABUS Prophecy and Current Events August 5………………Introduction: The Nature of Prophecy Ezekiel 38 - 39 Extra reading.………………………Ezekiel’s Temple August 12 …………………………………….………….. Daniel 7-9 August 19 ………………………………………. Jesus’ Teachings Revelation 7 Seals August 26 ………………………………. Revelation 7 Trumpets Revelation of the Antichrist/False Trinity 7 Bowls and a Wedding For this study, you will need the following tools: 1. A good Bible translation. An ESV, HCSB or NASB is preferred. In class I will be using the NASB unless otherwise stated. If a King James or New King James is used, please choose a text that is edited with the NU text notes if possible. A paraphrased Bible is not a good choice for this study. 2. A concordance or computer program with this tool that is keyed to the Bible translation you are using will be very helpful. 3. A notebook where you can record all of your findings on this topic for cross referencing in the future; the workbook is printed single sided to provide space for notes. Dr. JoLynn Gower, Executive Director Christian Resource Center [email protected] 217-493-6151 www.guardingthetruth.org 1 INTRODUCTION The Day of the Lord Prophecy is sometimes very difficult to study. Because it is hard, or we don’t even know how to begin, we frequently just don’t begin! However, God has given His Word to us for a reason. We would be wise to heed it. As we look at prophecy, it is helpful to have some insight into its nature. Prophets see events; they do not necessarily see the time between the events. -

Israelian Hebrew Features in Deuteronomy 33 Gary A

Israelian Hebrew Features in Deuteronomy 33 Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University Reprint from: N. S. Fox, D. A. Glatt-Gilad, and M. J. Williams, eds., Mishneh Todah: Studies in Deuteronomy and Its Cultural Environment in Honor of Jeffrey H. Tigay (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2009), pp. 167-183. The author apologizes for the repeated error that appears in the printed version of this article: in notes 32, 33, 51, 65, 69, and 82, the spelling Ma>agarim should be corrected to Ma<agarim. 00-TigayFs.book Page 167 Wednesday, January 21, 2009 10:45 AM Offprint from: Fox et al., ed., Mishneh Todah: Studies in Deuteronomy and Its Cultural Environment in of Jeffrey H. Tigay ç Copyright 2009 Eisenbrauns. All rights reserved. Israelian Hebrew Features in Deuteronomy 33 Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University In an article published 15 years ago, I called attention to a series of Israelian Hebrew (IH) features that appear in the blessings to the northern tribes in Genesis 49 (e.g., µrg ‘bone’ in the blessing to Issachar, rpv ‘beauty’ in the bless- ing to Naphtali, etc.).1 This essay, devoted to the similar blessings to the tribes in Deuteronomy 33, is a natural complement to that article. As we shall see, also in this poem one encounters grammatical forms and lexical items that reflect the regional dialects of the tribes. It gives me great pleasure to dedicate this essay to my friend and colleague Jeffrey H. Tigay, whose many publications have illumined the world of the Bible and the ancient Near East and whose commentary on Deuteronomy is a singu- lar achievement, destined to remain the standard work for years to come.2 I am especially delighted to develop further the succinct statement penned by our jubilarian in that volume: “It is also possible that the poem uses words or forms from regional variations of Hebrew spoken by the individual tribes.”3 1. -

RELI 3850: God in Israel: Historical Encounters NOTE THIS COURSE OUTLINE IS NOT FINAL UNTIL the FIRST DAY of CLASS

RELI 3850: God in Israel: Historical Encounters NOTE THIS COURSE OUTLINE IS NOT FINAL UNTIL THE FIRST DAY OF CLASS. The most up‐to‐date version of the syllabus is on CULearn CARLETON UNIVERSITY GOD IN ISRAEL: HISTORICAL ENCOUNTERS COLLEGE OF THE HUMANITIES RELI 3850: TOPICS IN STUDY OF RELIGION ABROAD RELIGION PROGRAM Israel: May 4‐27, 2014 Dr. Deidre Public course web site for info and uploading blogs [email protected] about the course www.carleton.ca/studyisrael Dr. Shawna Dolansky Official Course Facebook page: public fb page for [email protected] friends and families to see where we are going. Post photos, videos, tweet about the course. https://www.facebook.com/studyisraelwithZC CU Learn site for readings and grades Description: This third‐year travel course will survey religious history through geographical exploration of famous sites all over Israel: biblical Israel at the Temple Mount; origins of Christianity out of Judaism in the Galilee and in Jerusalem; Second Temple Judaism at Qumran and Masada; Rabbinic Judaism in ancient synagogues and in a special exhibit at the Israel Museum; the Crusades at the ruins of a Crusader fortress; Jewish mysticism in 17th century Safed; the Holocaust at Yad Vashem; modern Israel at the Knesset, a kibbutz, the Baha’i Temple in Haifa, and the beaches of Tel Aviv. Required Texts: Required readings This travel course includes travel in Israel from prepare you for class lectures, May 4‐27 with course requirements beginning discussions and site visits. Always read before travel. the required text prior to the site visit. Course Requirements: Required texts include online readings 30% Participation linked through the CU Learn web site 20% Presentation or Web Page 50% Blogs or Research paper see details below YOUR PROFESSORS: As the Jewish Studies specialist of the Religion Program, Professor Deidre Butler brings together her general expertise in Jewish Studies and Religion with an emphasis on contemporary Jewish life, modern Jewish thought, Holocaust, and gender and sexuality. -

Some Thoughts on Religious Change at Deir El-Medina

SOME THOUGHTS ON RELIGIOUS CHANGE AT DEIR EL-MEDINA Cathleen Keller University of California, Berkeley It gives me very great pleasure to contribute ticular, have met with some success: Baraize’s to a volume in honor of Richard Fazzini, a excavations in the Ptolemaic temple area;5 the fellow Egyptomania enthusiast and aficionado of clearance of the “oratorio” sacred to Ptah and ancient Thebes. I feel reasonably certain that Meretseger;6 Davies’ investigation of the “high the characters mentioned in this paper, though place,” situated above the path between Deir el- residents of the Western Side, were as familiar as Medina and the Valley of the Kings,7 and the he with the Temple of Mut at Karnak. Italian, German and French excavations of the The title of Keith Hopkins’s recent work on village itself, have yielded up some in situ ma- the religions of the Hellenistic Mediterranean, A terial.8 In addition to general surveys of reli- World Full of Gods,1 aptly describes the religious life gious cult and practice at Deir el-Medina,9 reli- of the workmen of Deir el-Medina as well. From gious studies of the Deir el-Medina “pantheon” the inception of the study of this organization, have frequently focused on individual deities, no- the votive monuments of the sdm.w-#sˇ m s.t-M3#.t tably the deified Amenhotep I10 and Ahmose- ¯ have attracted the attention of scholars.2 The Nefertari11 and Meretseger.12 Others, however, re- sheer quantity of the monuments, as well as the main understudied, including Hathor, the dedica- variety of the deities depicted3 (a list that includes tee of Deir el-Medina’s major sanctuary, and her divinities of both indigenous and foreign origin), interaction with her local sister-divinities, such as has led to their being used to illustrate general Meretseger and Henutimentet. -

2 Disambiguating Moses' Book Of

2 DISAMBIGUATING MOSES’ BOOK OF LAW Efforts to delineate the contents of Moses’ book of the law face the chal- lenge of a variety of ambiguous terms and references. The phrase “this law” -occurs nineteen times in Deuteronomy, five times in con ( ַה ָ תּוֹרה ַהזּ ֹאת) and once in connection with 85( ֵסֶפר) ”nection with the word “book ,The terms “law” and “book” are themselves ambiguous 86.( ֲאָבִנים) ”stones“ can mean “instruction” or “teaching” in addition to the law and ָ תּוֹרה since can denote any written surface, from an ancient scroll to engraved ֵסֶפר stone (Barton 1998:2, 13). In 31:9, the narrator reports that Moses wrote “this law” and handed the document over to the Levites and elders with instructions for periodic reading. A little later, the narrator reports that Moses wrote “the words of this law” in “a book” which he consequently handed over to the Levites for deposition beside the ark of the covenant (31:24). Added to the polyvalent terminology and multiple reports of writ- ing are the ancillary terms “testimonies,” “commandments,” “statutes,” and “ordinances” (e.g., 4:44-5). Scholars have resorted to various means to delineate a document bur- dened so with diverse signification. In the process, some scholars have fallen into debate over the swept volume of a plastered stele so that they might better determine whether the entire Deuteronomic (sic) text (chs. 1- 34) could have been etched on its surface (cf. 27:3). While Eugene H. Merrill argues that a plastered stele could not have contained the entire Deuteronomic text, (1994:342), Jeffrey H. -

From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2017 From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old estamentT imagery of Eden within the New Testament James Cregan The University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Cregan, J. (2017). From the Garden of Eden to the new creation in Christ : A theological investigation into the significance and function of the Old Testament imagery of Eden within the New Testament (Doctor of Philosophy (College of Philosophy and Theology)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/181 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM THE GARDEN OF EDEN TO THE NEW CREATION IN CHRIST: A THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION INTO THE SIGNIFICANCE AND FUNCTION OF OLD TESTAMENT IMAGERY OF EDEN WITHIN THE NEW TESTAMENT. James M. Cregan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, Australia. School of Philosophy and Theology, Fremantle. November 2017 “It is thus that the bridge of eternity does its spanning for us: from the starry heaven of the promise which arches over that moment of revelation whence sprang the river of our eternal life, into the limitless sands of the promise washed by the sea into which that river empties, the sea out of which will rise the Star of Redemption when once the earth froths over, like its flood tides, with the knowledge of the Lord. -

Introduction

Introduction Early Jewish Mysticism Although this investigation will focus mainly on the roots of the Metatron lore, this Jewish tradition cannot be fully understood without addressing its broader theological and historical context, which includes a religious movement known as early Jewish mysticism. Research must therefore begin with clarifying some notions and positions pertaining to the investigation of this broader religious phenomenon. The roots of the current scholarly discussion on the origin, aim, and content of early Jewish mysticism can be traced to the writings of Gershom Scholem. His studies marked in many ways a profound breach with the previous paradigm of 19th and early 20th century scholarship solidified in the Wissenschaft des Judentums movement which viewed Jewish mystical developments as based on ideas late and external to Judaism.1 In his seminal research, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, as well as other publications,2 Scholem saw his main task as clarifying the origins of early Jewish mysticism on the basis of new methodological premises, which, in contrast to the scholars of the Wissenschaft des Judentums, approached early Jewish mysticism as a genuine Jewish movement with roots in biblical and pseudepigraphic traditions. Scholem’s project was not an easy one, and in ————— 1 One of the representatives of this movement, Heinrich Graetz, considered the Hekhalot writings as late compositions dated to the end of the Geonic period. He viewed the Hekhalot literature as “a compound of misunderstood Agadas, and of Jewish, Christian, and Mahometan fantastic notions, clothed in mystical obscurity, and pretended to be a revelation.” H. Graetz, History of the Jews (6 vols.; Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1894) 3.153.