From the Garden of Eden to the New Creation in Christ : a Theological Investigation Into the Significance and Function of the Ol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Identification of “The Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon(Psssol1))

DOI: https://doi.org/10.28977/jbtr.2011.10.29.149 The Identification of “the Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon / Unha Chai 149 The Identification of “the Righteous” in the Psalms of Solomon(PssSol1)) Unha Chai* 1. The Problem The frequent references to “the righteous” and to a number of other terms and phrases2) variously used to indicate them have constantly raised the most controversial issue studied so far in the Psalms of Solomon3) (PssSol). No question has received more attention than that of the ideas and identity of the righteous in the PssSol. Different views on the identification of the righteous have been proposed until now. As early as 1874 Wellhausen proposed that the righteous in the PssSol refer to the Pharisees and the sinners to the Sadducees.4) * Hanil Uni. & Theological Seminary. 1) There is wide agreement on the following points about the PssSol: the PssSol were composed in Hebrew and very soon afterwards translated into Greek(11MSS), then at some time into Syriac(4MSS). There is no Hebrew version extant. They are generally to be dated from 70 BCE to Herodian time. There is little doubt that the PssSol were written in Jerusalem. The English translation for this study is from “the Psalms of Solomon” by R. Wright in The OT Pseudepigrapha 2 (J. Charlesworth, ed.), 639-670. The Greek version is from Septuaginta II (A. Rahlfs, ed.), 471-489; G. W. E. Nickelsburg, Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishnah, 203-204; K. Atkinson, “On the Herodian Origin of Militant Davidic Messianism at Qumran: New Light From Psalm of Solomon 17”, JBL 118 (1999), 440-444. -

Ezekiel 17:22-24 JESUS: the SHOOT from WHICH the CHURCH GREW Rev

Ezekiel 17:22-24 JESUS: THE SHOOT FROM WHICH THE CHURCH GREW Rev. John E. Warmuth Sometimes when preaching on Old Testament texts, especially gospel promises like this one, a brief review of Old Testament history leading up to the prophecy helps to understand the prophecy. That’s because these gospel promises were given to bring comfort and joy to hearts that were hurting under specific consequences for specific sins. We begin our brief review at the time of King David. Under his rule Israel was a power to be reckoned with. In size it was nearly as big as it would ever be. It was prosperous. Spiritually, it worshipped the true God and enjoyed his fellowship. The people looked forward to King David’s “greater son,” the Christ, the Savior to come. Under King Solomon, David’s son, the nation continued to prosper, worldly speaking. But as often happens, worldly prosperity brought spiritual depravity. False gods found their way into the people’s lives. After Solomon died the nation was split into the northern kingdom of Israel and the southern kingdom of Judah. The kings of the northern kingdom all worshiped false gods and led the people to do the same. God sent prophets who warned them of their sin and urged them to turn them back to God. Meanwhile, in the southern kingdom of Judah, some kings were faithful to God and set the example for the nation while others were not. God finally became fed up with the sin of the northern kingdom and sent the Assyrian Empire to destroy it. -

Gog and Magog Battle Israel

ISRAEL IN PROPHECY LESSON 5 GOG AND MAGOG BATTLE ISRAEL The “latter days” battle against Israel described in Ezekiel is applied by dispensationalists to a coming battle against the modern nation of Israel in Palestine. The majority of popular Bible commentators try to map out this battle and even name nations that will take part in it. In this lesson you will see that this prophecy in Ezekiel chapters 36 and 37 does not apply to the modern nation of Israel at all. You will study how the book of Revelation gives us insights into how this prophecy will be applied to God’s people, spiritual Israel (the church) in the last days. You will also see a clear parallel between the events described in Ezekiel’s prophecy and John’s description of the seven last plagues in Revelation. This prophecy of Ezekiel gives you another opportunity to learn how the “Three Fold Application” applies to Old Testament prophecy. This lesson lays out how Ezekiel’s prophecy was originally given to the literal nation of Israel at the time of the Babylonian captivity, and would have met a victorious fulfillment if they had remained faithful to God and accepted their Messiah, Jesus Christ. However, because of Israel’s failure this prophecy is being fulfilled today to “spiritual Israel”, the church in a worldwide setting. The battle in Ezekiel describes Satan’s last efforts to destroy God’s remnant people. It will intensify as we near the second coming of Christ. Ezekiel’s battle will culminate and reach it’s “literal worldwide in glory” fulfillment at the end of the 1000 years as described in Revelation chapter 20. -

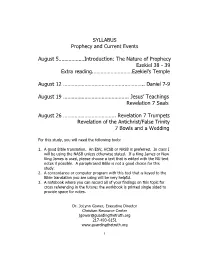

Prophecy and Current Events

SYLLABUS Prophecy and Current Events August 5………………Introduction: The Nature of Prophecy Ezekiel 38 - 39 Extra reading.………………………Ezekiel’s Temple August 12 …………………………………….………….. Daniel 7-9 August 19 ………………………………………. Jesus’ Teachings Revelation 7 Seals August 26 ………………………………. Revelation 7 Trumpets Revelation of the Antichrist/False Trinity 7 Bowls and a Wedding For this study, you will need the following tools: 1. A good Bible translation. An ESV, HCSB or NASB is preferred. In class I will be using the NASB unless otherwise stated. If a King James or New King James is used, please choose a text that is edited with the NU text notes if possible. A paraphrased Bible is not a good choice for this study. 2. A concordance or computer program with this tool that is keyed to the Bible translation you are using will be very helpful. 3. A notebook where you can record all of your findings on this topic for cross referencing in the future; the workbook is printed single sided to provide space for notes. Dr. JoLynn Gower, Executive Director Christian Resource Center [email protected] 217-493-6151 www.guardingthetruth.org 1 INTRODUCTION The Day of the Lord Prophecy is sometimes very difficult to study. Because it is hard, or we don’t even know how to begin, we frequently just don’t begin! However, God has given His Word to us for a reason. We would be wise to heed it. As we look at prophecy, it is helpful to have some insight into its nature. Prophets see events; they do not necessarily see the time between the events. -

The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries, Inc

The Council on Botanical and Horticultural Libraries, Inc. Newsletter Number 94 August 2004 Annual Meeting Evaluation Summary Facilities DOUGLAS HOLLAND, CURATOR OF LIBRARY SERVICES & TECHNOLOGY The general meeting facilities were almost unanimously rated MISSOURI BOTANICAL GARDEN “Excellent.” The meals and breaks were evenly split between SAINT LOUIS, MISSOURI “excellent” and “good” with a few comments on the morning continental breakfasts, suggesting both not having them at As those of you who attended the meeting know, we had a all, and having more “healthy” foods. There were several com- slight problem with the mail service and the timely arrival of ments about the banquet. Though folks enjoyed themselves, the evaluation forms. The forms I mailed to Chuck a week many felt that the food and service were not up to the quality before the meeting finally arrived in Pittsburgh, about two of the rest of the meeting. One complaint mentioned several weeks after the meeting! So despite the reprinting and late times was the lack of wine at the banquet. delivery of the forms to the meeting attendees, we had 41 evalu- ations returned. That is 59% of the 70 attendees at the meet- Everyone agreed that the hotel and dorm facilities were either ing. The overwhelming number of comments and general feel- “excellent” or “good.” One omission Yours Truly made on the ing of the results were that this was a really interesting and form was forgetting to separate the questions for dorm and well-run conference. hotel accommodations. Ten people were clever enough to scratch out “hotel” and write in “dorm” to let me know which Business meetings they were rating. -

E Z E K I E L

E Z E K I E L —prophet to the exiles in Babylon, early sixth century. Name means “God will strengthen” 1. Date Ezekiel dates his prophecies very frequently, as much or more than any other OT book. There are 14 time-posts in Ezekiel, all in chronological order except 29:17 that has a logical connection to its context of Oracles against the Nations: 1:1 30th year (of what?) 1:2 5th year of Jehoiachin’s captivity 8:1 6th “ 20:1 7th 24:1 9th 26:1 11th 29:1 10th 29:17 27th 30:20 11th 31:1 11th 32:1 12th 32:17 12th 33:21 12th year of our captivity 40:1 25th “ Jehoiachin’s captivity started in 597 BC, the apparent terminus a quo: 5th year = 593 BC 27th year = 571 BC Note that many of these prophecies were given during his 11th and 12th years of captivity. That would be 587-586 BC, just during and after the fall and destruction of Jerusalem (cf. 33:21). Ezekiel 1:1 poses a question: the “30th year” of what? It could be the 30th year of the Neo-Babylonian empire (about 596 BC, assuming its beginnings under Nabopolassar in 626 BC), the year after Jehoiachin was taken captive, two years before Ezekiel’s call related in chapter 1. Another possibility is that it is Ezekiel’s age at the time of his call (cf. Num. 4:3, and the lives of John the Baptist and of Jesus, Lk. 3:23). The old critical view of C. -

Newly Discovered – the First River of Eden!

NEWLY DISCOVERED – THE FIRST RIVER OF EDEN! John D. Keyser While most people worry little about pebbles unless they are in their shoes, to geologists pebbles provide important, easily attained clues to an area's geologic composition and history. The pebbles of Kuwait offered Boston University scientist Farouk El-Baz his first humble clue to detecting a mighty river that once flowed across the now-desiccated Arabian Peninsula. Examining photos of the region taken by earth-orbiting satellites, El-Baz came to the startling conclusion that he had discovered one of the rivers of Eden -- the fabled Pishon River of Genesis 2 -- long thought to have been lost to mankind as a result of the destructive action of Noah's flood and the eroding winds of a vastly altered weather system. This article relates the fascinating details! In Genesis 2:10-14 we read: "Now a river went out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it parted and became FOUR RIVERHEADS. The name of the first is PISHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of HAVILAH, where there is gold. And the gold of that land is good. Bdellium and the onyx stone are there. The name of the second river is GIHON; it is the one which encompasses the whole land of Cush. The name of the third river is HIDDEKEL [TIGRIS]; it is the one which goes toward the east of Assyria. The fourth river is the EUPHRATES." While two of the four rivers mentioned in this passage are recognisable today and flow in the same general location as they did before the Flood, the other two have apparently disappeared from the face of the earth. -

Ezekiel 47:13-23 NASB Large Print Commentary

International Bible Lessons Commentary Ezekiel 47:13-23 New American Standard Bible International Bible Lessons Sunday, November 23, 2014 L.G. Parkhurst, Jr. The International Bible Lesson (Uniform Sunday School Lessons Series) for Sunday, November 23, 2014, is from Ezekiel 47:13-23. Questions for Discussion and Thinking Further follow the verse-by- verse International Bible Lesson Commentary below. Study Hints for Thinking Further, a study guide for teachers, discusses the five questions below to help with class preparation and in conducting class discussion; these hints are available on the International Bible Lessons Commentary website. The weekly International Bible Lesson is usually posted each Saturday before the lesson is scheduled to be taught. International Bible Lesson Commentary Ezekiel 47:13-23 (Ezekiel 47:13) Thus says the Lord GOD, “This shall be the boundary by which you shall divide the land for an inheritance among the twelve tribes of Israel; Joseph shall have two portions. 2 In Ezekiel 47:13-20, Ezekiel received instructions on how the Promised Land should be divided among the 12 tribes after they returned from exile. The Levites received some cities, a portion of the offerings, and lived among the other 12 tribes: Joseph’s descendants had been divided into two tribes, leaving 12 tribes to inherit the land. Since the returning exiles did not obey the vision that God gave Ezekiel, they did not divide the land according to Ezekiel’s vision either. (Ezekiel 47:14) “You shall divide it for an inheritance, each one equally with the other; for I swore to give it to your forefathers, and this land shall fall to you as an inheritance. -

Arboreal Metaphors and the Divine Body Traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham Andrei Orlov Marquette University

Arboreal Metaphors and the Divine Body Traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham Andrei Orlov Marquette University The first eight chapters of theApocalypse of Abraham, a Jewish pseudepigraphon preserved solely in its Slavonic translation, deal with the early years of the hero of the faith in the house of his father Terah. The main plot of this section of the For the published Slavonic manuscripts and fragments of Apoc. Ab., see Ioan Franko, “Книга о Аврааме праотци и патриарси” [“The Book about the Forefather and the Patriarch Abraham”], in Апокрiфи i легенди з украiнських рукописiв [The Apocrypha and the Legends From the Ukrainian Manuscripts] (5 vols.; Monumenta Linguae Necnon Litterarum Ukraino-Russicarum [Ruthenicarum]; Lvov, Ukraine, 1896–1910) 1:80–86; Alexander I. Jacimirskij, “Откровение Авраама” [“The Apocalypse of Abraham”], in Апокрифы ветхозаветные [The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha] (vol. 1 of Библиографический обзор апокрифов в южнославянской и русской письменности [The Bibliographical Survey of Apocryphal Writings in South Slavonic and Old Russian Literature]; Petrograd: The Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1921) 99–100; Petr P. Novickij, ed., “Откровение Авраама” [“The Apocalypse of Abraham”], in Общество любителей древней письменности [The Society of Lovers of Ancient Literature] 99.2 (St. Petersburg: Markov, 1891); Ivan Ja. Porfir’ev, “Откровение Авраама” [“The Apocalypse of Abraham”], in Апокрифические сказания о ветхозаветных лицах и событиях по рукописям соловецкой библиотеки [The Apocryphal Stories about Old Testament Characters and Events according to the Manuscripts of the Solovetzkoj Library] (Sbornik Otdelenija russkogo jazyka i slovesnosti Imperatorskoj akademii nauk 17.1; St. Petersburg: The Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences, 1877) 111–30; Belkis Philonenko- Sayar and Marc Philonenko, L’Apocalypse d’Abraham. -

Current Trends in Green Urbanism and Peculiarities of Multifunctional Complexes, Hotels and Offices Greening

Ukrainian Journal of Ecology Ukrainian Journal of Ecology, 2020, 10(1), 226-236, doi: 10.15421/2020_36 REVIEW ARTICLE UDK 364.25: 502.313: 504.75: 635.9: 711.417.2/61 Current trends in Green Urbanism and peculiarities of multifunctional complexes, hotels and offices greening I. S. Kosenko, V. M. Hrabovyi, O. A. Opalko, H. I. Muzyka, A. I. Opalko National Dendrological Park “Sofiyivka”, National Academy of Science of Ukraine Kyivska St. 12а, Uman, Ukraine. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 10.02.2020 Accepted 06.03.2020 The analysis of domestic and world publications on the evolution of ornamental garden plants use from the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and ancient Romans to the “dark times” of the middle Ages and the subsequent Renaissance was carried out. It was made in order to understand the current trends of Green Urbanism and in particular regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public spaces. The aim of the article is to grasp current trends of Green Urbanism regarding the diversity of floral and ornamental arrangements used in the design of modern interiors of public premises. Cross-cultural comparative methods have been used, partially using the hermeneutics of old-printed texts in accordance with the modern system of scientific knowledge. The historical antecedents of ornamental gardening, horticulture, forestry and vegetable growing, new trends in the ornamental plants cultivation, modern aspects of Green Urbanism are discussed. The need for the introduction of indoor plants in the residential and office premises interiors is argued in order to create a favorable atmosphere for work and leisure. -

The Prophecy of Ezekiel 38-39

1 WHAT EZEKIEL 38-39 REVEALS About A FUTURE WORLD WAR III By Steven M. Collins P.O. Box 88735 Sioux Falls, SD 571009-1005 Introduction and Context: The “latter day” prophecy found in Ezekiel 38-39 has long been seen by many Christians as a key prophecy describing events which will occur among the nations in the time preceding the Millennium (or Messianic Age). This is a lengthy and very “meaty” prophecy which needs a thorough examination in order to be understood and appreciated. This research paper has been prompted by the fact that so much is happening in world events which is directly setting the stage for the fulfillment of this prophecy in future world geopolitics. It is needful to warn as many people as possible about what will occur in the years ahead of us, because when it is fulfilled, it will shock all nations and it will drastically affect the lives of everyone on the planet. Ezekiel 38- 39 reveals, in advance, many details about a future World War III which will occur in the years ahead of us. What is noteworthy about this prophecy is that it has God’s “guarantee” that he will personally intervene as needed to make sure it comes to pass exactly as prophesied. If you are interested in knowing the future, consider what Ezekiel 38-39 has to say. If you doubt that there is a Creator God who can influence or control world events, your doubts will also be addressed in this report. As a reassurance to all potential readers, this research paper will not “grind an ax” for or against any religious denomination and it will not ask you for money. -

The Meaning and Identification of God's Eschatological Trumpets

Scholars Crossing SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 2001 The Meaning and Identification of God's Eschatological Trumpets James A. Borland Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Borland, James A., "The Meaning and Identification of God's Eschatological Trumpets" (2001). SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations. 78. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. l~e me3nin~ 3n~ l~entific3tion of Gof Gfschatolo~icall rumpets JAMES A. BORLAND Liberty University God's eschatological trumpets 1 have probably sparked disproportionately more interest than their scant mention in Scripture might warrant. These trumpets frequently playa role in establishing one's chronology of the end times, especially in the debate between pre- and posttribulation rapture pro ponents. 2 To elucidate this issue more fully we will examine the broad bib lical usage of trumpets to ascertain their nature and function. In this way one can better approach the question of the meaning and identification of God's eschatological trumpets. Trumpets, both human and divine, appear over 140 times in the Bible. The Old Testament contains slightly over 90 percent of these references,3 1. Matt. 24:31; 1 Cor. 15:52; and 1 Thess. 4:16. 2. Typical of the debate over these trumpets would be Thomas Ice and Kenneth L. Gentry Jr., The Great Tribulation: Past or Futltre? Two Evangelicals Debate the Question (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1999), 61-65, 157-58; Marvin Rosenthal's The Pre- Wrath Rapture of the Church (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 1990), 187-94, answered by Paul S.