Thar Coal Project and Local Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annexure D: Thar Coal Analysis

American Journal of Scientific Research 160 ISSN 1450-223X Issue 11(2010), pp.92-102 Annexure-'D' © EuroJournals Publishing, Inc. 2010 http://www.eurojournals.com/ajsr.htm Composition, Trace Element Contents and Major Ash Constituents of Thar Coal, Pakistan M. Afzal Farooq Choudry Department of Environmental Science, FUUAST, Karachi, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Yasmin Nurgis Environmental Research Center, Bahria University, Karachi, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Mughal Sharif Environmental Research Center, Bahria University, Karachi, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Amjad Ali Mahmood Geological Survey of Pakistan, Karachi, Pakistan Haq Nawaz Abbasi Department of Environmental Science, FUUAST, Karachi, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Thar coalfield is a part of the Thar Desert of Pakistan. Pakistan has coal reserves of 185 billion tons, of this Thar coal reserves account for 175 billion tons spread over a single geographically contained area of 9100 sq km in the south eastern part of the Sindh. It is bounded in the north, east and south by India, in the west by the irrigated Indus river flood plain. The terrain is sandy and rough with sand dunes forming the topography. Various physio-chemical parameters including chemical composition of coal ashes, distribution of trace elements in them, were analyzed to understand the coal prospects and its share in the domestic energy production. In addition a preliminary study have also undertaken on the factors that effect the chemical composition of coal ashes. The apparent rank is high volatile Lignite “B” coal. Arithmetic mean values for proximate analysis of coals (as received basis; n=54) show these coals to be 6.83% Ash, 29.55% volatile matter, 19.2% fixed carbon and 44.3% moisture and have a heat of combustion of 6094 BTU/lb. -

Spatial Drought Monitoring in Thar Desert Using Satellite-Based Drought Indices and Geo-Informatics Techniques †

Proceedings Spatial Drought Monitoring in Thar Desert Using Satellite-Based Drought Indices and Geo-Informatics Techniques † Muhammad Bilal 1, Muhammad Usman Liaqat 1,*, Muhammad Jehanzeb Masud Cheema 1,2, Talha Mahmood 1 and Qasim Khan 3 1 Department of Irrigation and Drainage, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad 38000, Pakistan; [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (M.J.M.C.); [email protected] (T.M.) 2 USPCAS-AFS, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad 38000, Pakistan 3 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, United Arab Emirates University, Al Ain 15551, UAE; [email protected] or [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +971-503-646-784 † Presented at the 2nd International Electronic Conference on Water Sciences, 16–30 November 2017; Available online: http://sciforum.net/conference/ecws-2. Published: 16 November 2017 Abstract: Drought is a continuous process in Thar Desert, Pakistan. The extent of this drought needs to be assessed for future land use and adaptation. The effect of previous drought on vegetation cover of the Thar region was studied, through combined use of drought indices and geographic information (GIS) techniques. Five years (2002, 2005, 2008, 2011 and 2014) were selected to analyze the drought conditions and land use pattern of the Thar region. The drought indices used in this study included the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) and the Standard Precipitation Index (SPI). Images of past drought were compared with post-drought images of our targeted area and land use maps were developed for spatio-temporal analysis. The results of the study revealed that vegetation in Thar showed an improving trend from 2002 to 2011 and then declined from 2011 to 2014. -

1 Sindh Flood Response 2011 FINAL REPORT

Sindh Flood Response 2011 FINAL REPORT (OCT 18, 2011 – FEB 29, 2012) AID-OFDA-G-12-00003 Funded by: United States Agency for International Development Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance USAID/OFDA Organization: Mercy Corps Date: May 31, 2011 HQ Address: 45 SW Ankeny St Portland, OR, 97204, USA USA Pakistan Peter O'Farrell Steve Claborne, Country Director Senior Program Officer, South Asia Tel: (92) 300-501-2340 Tel.: (1) 503-896-5849 E-mail : [email protected] Fax: (1) 503-896-5013 House #36, Street #1, F/6-3 Email: [email protected] Islamabad, Pakistan Country/Region: Pakistan, Districts Badin and Mirpur Khas in Southern Sindh. Mercy Corps, Pakistan ͳ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The monsoon rains that started in the second week of August 2011 triggered serious flooding affecting more than 5.3 million people. It is reported to have destroyed or damaged nearly one million houses and inundated 4.2 million acres of cropland, prompting the Government of Pakistan to call for support from the United Nations. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) for Sindh mobilized its resources relatively quickly, however their response was far too limited compared with the needs of so many people. During the contingency planning phase, they estimated resources adequate to the temporary care of some 50,000 IDPs. The situation had worsened nearly a month after the start of the emergency and the national authorities requested international support. At that point, the NDMA and PDMA indicated that between 5.3 million flood-affected people of Lower Sindh were in urgent need of assistance. -

Nutrition and Mortality Survey

NUTRITION AND MORTALITY SURVEY Tharparkar, Sanghar and Kamber Shahdadkhot districts of Sindh Province, Pakistan 18-25 March, 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ................................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2. Objective of the Study ............................................................................................................................... 6 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................................. 7 3.1 Study area ......................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Study population .............................................................................................................................. 7 3.3 Study design ...................................................................................................................................... 8 3.3.1 Sample size -

Final Merit List of Candidates Applied for Admission in Bs Medical Laboratory

BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION - 2020-2021 FINAL MERIT LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR ADMISSION IN BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION 2020-2021 LIAQUAT UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, JAMSHORO DISTRICT - BADIN (BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) - 01 - SEAT - MERIT) Test Test Int. Total Merit Inter A / Level Test Form No. Name of Candidates Fathers Name Surname Gender DOB District Seat Marks 50% score Positon Obt 50% Year Inter% Grade No. Marks 1 4841 Habesh Kumar Veero Mal Khattri Male 1/11/2001 BADIN 2019 905 82.273 A1 719 82 41 41.136 82.136 District: BADIN - WAITING Menghwar 1496 Akash Kumar Mansingh Male 10/16/2001 BADIN 2020 913 83 A1 167 78 39 41.5 80.5 2 Bhatti 3 1215 Janvi Papoo Kumar Lohana Female 2/11/2002 BADIN 2020 863 78.455 A 894 82 41 39.227 80.227 4 3344 Bushra Muhammad Ayoub Kamboh Female 9/30/2000 BADIN 2019 835 75.909 A 490 82 41 37.955 78.955 5 1161 Chanderkant Papoo Kumar Lohana Male 3/8/2003 BADIN 2020 889 80.818 A1 503 76 38 40.409 78.409 6 3479 Bushra Amjad Amjad Ali Jat Female 4/20/2001 BADIN 2019 848 77.091 A 494 73 36.5 38.545 75.045 7 4306 Noor Ahmed Ghulam Muhammad Notkani Male 10/12/2001 BADIN 2020 874 79.455 A 1575 70 35 39.727 74.727 Muhammad Talha 2779 Hasan Nasir Rajput Male 7/21/2001 BADIN 2020 927 84.273 A1 1378 65 32.5 42.136 74.636 8 Nasir 9 3249 Vandna Dev Anand Lohana Female 3/21/2002 BADIN 2020 924 84 A1 2294 65 32.5 42 74.5 10 2231 Sanjai Eshwar Kumar Luhano Male 8/17/2000 BADIN 2020 864 78.546 A 1939 70 35 39.273 74.273 RANA RAJINDAR 3771 RANA AMAR -

Solutions for Energy Crisis in Pakistan I

Solutions for Energy Crisis in Pakistan i ii Solutions for Energy Crisis in Pakistan Solutions for Energy Crisis in Pakistan iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This volume is based on papers presented at the two-day national conference on the topical and vital theme of Solutions for Energy Crisis in Pakistan held on May 15-16, 2013 at Islamabad Hotel, Islamabad. The Conference was jointly organised by the Islamabad Policy Research Institute (IPRI) and the Hanns Seidel Foundation, (HSF) Islamabad. The organisers of the Conference are especially thankful to Mr. Kristof W. Duwaerts, Country Representative, HSF, Islamabad, for his co-operation and sharing the financial expense of the Conference. For the papers presented in this volume, we are grateful to all participants, as well as the chairpersons of the different sessions, who took time out from their busy schedules to preside over the proceedings. We are also thankful to the scholars, students and professionals who accepted our invitation to participate in the Conference. All members of IPRI staff — Amjad Saleem, Shazad Ahmad, Noreen Hameed, Shazia Khurshid, and Muhammad Iqbal — worked as a team to make this Conference a success. Saira Rehman, Assistant Editor, IPRI did well as stage secretary. All efforts were made to make the Conference as productive and result oriented as possible. However, if there were areas left wanting in some respect the Conference management owns responsibility for that. iv Solutions for Energy Crisis in Pakistan ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank Bcf Billion Cubic Feet BCMA -

Power Project at Keti Bundar

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM 2X660 MW IMPORTED/THAR COAL POWER PROJECTS AT KETI BANDER SINDH COAL AUTHORITY ENERGY DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF SINDH Bungalow No.16 E Street, Zamzama Park, DHA Phase-V, Karachi. Phone: 99251507 1 THE LAND AND THE GOVERNMENT Pakistan, a land of many splendors and opportunities, the repository of a unique blend of history and culture from the East and the west, the cradle of one of the oldest civilizations which developed around the Indus Valley. It is the ninth most popular country of the world with 132.35 million tough, conscientious, hard working people, wishing and striving hard to enter into the 21st century as equal partners in the community of developed nations. It is located between 23 and 37 degrees latitude north and 61 and 76 degrees longitude east. Flanked by Iran and land- locked Afghanistan in the west and the Central Asian Republics and China in the north, Pakistan can rightly boost of having a significant location advantages with a vast only partially tapped market of 200 million people. The affluent Gulf States are just across the Arabian Sea to the south and provide an additional opportunity of a high consumption market. The geographical location, with one of the highest peaks of the world in the north and vast plains in the south, offers an unusual diversity of temperatures ranging from sub-zero levels on the mountains in winter to scorching heat in the plains in summer, providing friendly habitat to exquisite range of flora and fauna and a large variety of agricultural crops used for both foods and raw material for industries. -

Bird Conservation International Population and Spatial Breeding

Bird Conservation International http://journals.cambridge.org/BCI Additional services for Bird Conservation International: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Population and spatial breeding dynamics of a Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis colony in Sindh Province, Pakistan CAMPBELL MURN, UZMA SAEED, UZMA KHAN and SHAHID IQBAL Bird Conservation International / FirstView Article / December 2014, pp 1 - 11 DOI: 10.1017/S0959270914000483, Published online: 16 December 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0959270914000483 How to cite this article: CAMPBELL MURN, UZMA SAEED, UZMA KHAN and SHAHID IQBAL Population and spatial breeding dynamics of a Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis colony in Sindh Province, Pakistan. Bird Conservation International, Available on CJO 2014 doi:10.1017/S0959270914000483 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BCI, IP address: 82.152.44.144 on 17 Dec 2014 Bird Conservation International, page 1 of 11 . © BirdLife International, 2014 doi:10.1017/S0959270914000483 Population and spatial breeding dynamics of a Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis colony in Sindh Province, Pakistan CAMPBELL MURN , UZMA SAEED , UZMA KHAN and SHAHID IQBAL Summary The Critically Endangered Oriental White-backed Vulture Gyps bengalensis has declined across most of its range by over 95% since the mid-1990s. The primary cause of the decline and an ongoing threat is the ingestion by vultures of livestock carcasses containing residues of non- steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, principally diclofenac. Recent surveys in Pakistan during 2010 and 2011 revealed very few vultures or nests, particularly of White-backed Vultures. -

Tando Muhammad Khan

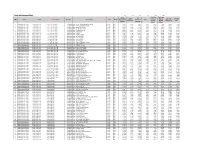

Tando Muhammad Khan 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010002 GBPS - YAR M. KANDRA@PIR BUX KANDRA Primary Boys 9,117 1,823 7,294 1,823 1,823 7,294 29,175 7,294 2 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010016 GBPS - YAR MUHAMMAD KANDRA Primary Boys 11,323 2,265 9,058 2,265 2,265 9,058 36,233 9,058 3 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010017 GBPS - KHUDA BUX GUMB Primary Boys 14,353 2,871 11,482 2,871 2,871 11,482 45,929 11,482 4 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010022 GBPS - ALAM KHAN TALPUR Primary Boys 44,542 8,908 35,634 8,908 8,908 35,634 142,535 35,634 5 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010025 GBPS - PALIO GHUMRANI Primary Boys 28,220 5,644 22,576 5,644 5,644 22,576 90,303 22,576 6 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010026 GBPS - KARIMABAD Primary Boys 28,690 5,738 22,952 5,738 5,738 22,952 91,808 22,952 7 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. -

Tharparkar Calamity – 2014

st 1 1 Situation Analysis Survey Tharparkar Calamity – 2014 1st Situation Analysis Survey - Tharparkar March –2014 Conducted by HANDS &Technically Facilitated by UN-OCHA st 2 1 Situation Analysis Survey Tharparkar Calamity – 2014 Table of Contents Title 1. Acknowledgement: .....................................................................................................................3 2. Introduction: ..............................................................................................................................3 3. .... Research Methodology and Sample design: ……………………………………………………………………………….3 4. Demographic Information: ..........................................................................................................4 Areas with greatest needs ........................................................................................................................ 5 Number of Key Informants ....................................................................................................................... 5 5. Key Findings ...............................................................................................................................5 5.1.1 Food security ............................................................................................................................. 7 Main Livelihood Sources ........................................................................................................................... 7 5.1.2 Livelihood source losses ........................................................................................................... -

Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Tharparkar District

PAKISTAN - Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Tharparkar District Union council ranking exercise, coordinated by UNOCHA and UNDP, is a joint effort of Government and humanitarian partners Community Restoration Food Education in the notified districts of 2011 floods in Sindh. Its purpose is to: SANGHAR SANGHAR SANGHAR Parno Gadro Parno Gadro Parno Gadro Identify high priority union councils with outstanding needs. Pirano Pirano Pirano Jo Par Jo Par Jo Par Facilitate stackholders to plan/support interventions and divert INDIA INDIA INDIA UMERKOT UMERKOT Tar Ahmed Tar Ahmed UMERKOT Tar Ahmed Mithrio Mithrio Mithrio resources where they are most needed. Charan Charan Charan MATIARI Sarianghiar MATIARI Sarianghiar MATIARI Sarianghiar Provide common prioritization framework to clusters, agencies Vejhiar Chachro Vejhiar Chachro Vejhiar Chachro Kantio Hirar Tardos Kantio Hirar Tardos Kantio Hirar Tardos Mithrio Mithrio Mithrio and donors. Chelhar Charan Chelhar Charan Chelhar Charan Satidero Satidero Satidero First round of this exercise is completed from February - March Mohrano Islamkot Mohrano Islamkot Mohrano Islamkot Mithrio Singaro Tingusar Mithrio Singaro Tingusar Mithrio Singaro Tingusar Bhitaro Bhatti Bhitaro Bhatti Bhitaro Bhatti BADIN Joruo BADIN Joruo BADIN Joruo 2012. Khario Harho Khario Harho Khario Harho Khetlari Ghulam Nagarparkar Khetlari Ghulam Nagarparkar Khetlari Ghulam Nagarparkar Shah Shah Shah Malanhori Mithi Malanhori Mithi Malanhori Mithi Virawah Virawah Virawah Sobhiar Vena Sobhiar Vena Sobhiar Vena Pithapur -

BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES

Heritage Foundation’s DRR-COMPLIANT SUSTAINABLE CONSTRUCTION BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES DRR-DRIVEN POST-FLOOD REHABILITATION IN SINDH Introduction to Heritage Foundation eritage Foundation established in 1980 is a Pakistan- based, not-for-profit, social and cultural entrepreneur organization engaged in research, publication and Hconservation of Pakistan’s cultural heritage. The Foundation has been instrumental in saving a large num- ber of heritage treasures and, as UNESCO team leader 2003- 2005, undertook the stabilization of the endangered Shish Ma- hal ceiling of the 16th c. Lahore Fort World Heritage Site. The Foundation publishes monographs and documents relat- ing to heritage and history of Pakistan as well as guides for her- itage safeguarding aspects. It has published a series of invento- ries of historic assets as National Register of Historic Places of Pakistan. In the National Register series, in addition to several Karachi documents listing over 600 historic buildings, docu- ments covering parts of Peshawar, the Siran Valley, Hazara District and Azad Kashmir have been published. Since 2000, its outreach arm KaravanPakistan has involved communities and youth in heritage safeguarding activities. Since 2005, as part of Heritage for Rehabilitation and Devel- opment Program, in partnership with Nokia and Nokia Sie- mens Network, Heritage Foundation has carried out work of rehabilitation of communities, particularly women, affected by the Earthquake 2005 in Northern Pakistan. A 3-year pro- gram, suppported by Scottish Government Fund, Glasgow University and Scottish Pakistan Association on disaster risk resistance (DRR) focusing on women is currently being car- ried out in the Siran Valley. The establishment of KIRAT, Kar- avanPakistan Institute for Research and Training in 2008 has helped in carrying out research and training on varied aspect of sustainable construction techniques drawn from traditional materials and vernacular methods.