Historical Sketch of Peasant Activism: Tracing Emancipatory Political Strategies of Peasant Activists of Sindh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Sindh Flood Response 2011 FINAL REPORT

Sindh Flood Response 2011 FINAL REPORT (OCT 18, 2011 – FEB 29, 2012) AID-OFDA-G-12-00003 Funded by: United States Agency for International Development Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance USAID/OFDA Organization: Mercy Corps Date: May 31, 2011 HQ Address: 45 SW Ankeny St Portland, OR, 97204, USA USA Pakistan Peter O'Farrell Steve Claborne, Country Director Senior Program Officer, South Asia Tel: (92) 300-501-2340 Tel.: (1) 503-896-5849 E-mail : [email protected] Fax: (1) 503-896-5013 House #36, Street #1, F/6-3 Email: [email protected] Islamabad, Pakistan Country/Region: Pakistan, Districts Badin and Mirpur Khas in Southern Sindh. Mercy Corps, Pakistan ͳ EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The monsoon rains that started in the second week of August 2011 triggered serious flooding affecting more than 5.3 million people. It is reported to have destroyed or damaged nearly one million houses and inundated 4.2 million acres of cropland, prompting the Government of Pakistan to call for support from the United Nations. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) and the Provincial Disaster Management Authority (PDMA) for Sindh mobilized its resources relatively quickly, however their response was far too limited compared with the needs of so many people. During the contingency planning phase, they estimated resources adequate to the temporary care of some 50,000 IDPs. The situation had worsened nearly a month after the start of the emergency and the national authorities requested international support. At that point, the NDMA and PDMA indicated that between 5.3 million flood-affected people of Lower Sindh were in urgent need of assistance. -

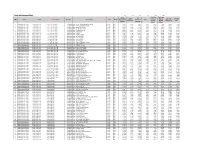

Final Merit List of Candidates Applied for Admission in Bs Medical Laboratory

BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION - 2020-2021 FINAL MERIT LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR ADMISSION IN BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION 2020-2021 LIAQUAT UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, JAMSHORO DISTRICT - BADIN (BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) - 01 - SEAT - MERIT) Test Test Int. Total Merit Inter A / Level Test Form No. Name of Candidates Fathers Name Surname Gender DOB District Seat Marks 50% score Positon Obt 50% Year Inter% Grade No. Marks 1 4841 Habesh Kumar Veero Mal Khattri Male 1/11/2001 BADIN 2019 905 82.273 A1 719 82 41 41.136 82.136 District: BADIN - WAITING Menghwar 1496 Akash Kumar Mansingh Male 10/16/2001 BADIN 2020 913 83 A1 167 78 39 41.5 80.5 2 Bhatti 3 1215 Janvi Papoo Kumar Lohana Female 2/11/2002 BADIN 2020 863 78.455 A 894 82 41 39.227 80.227 4 3344 Bushra Muhammad Ayoub Kamboh Female 9/30/2000 BADIN 2019 835 75.909 A 490 82 41 37.955 78.955 5 1161 Chanderkant Papoo Kumar Lohana Male 3/8/2003 BADIN 2020 889 80.818 A1 503 76 38 40.409 78.409 6 3479 Bushra Amjad Amjad Ali Jat Female 4/20/2001 BADIN 2019 848 77.091 A 494 73 36.5 38.545 75.045 7 4306 Noor Ahmed Ghulam Muhammad Notkani Male 10/12/2001 BADIN 2020 874 79.455 A 1575 70 35 39.727 74.727 Muhammad Talha 2779 Hasan Nasir Rajput Male 7/21/2001 BADIN 2020 927 84.273 A1 1378 65 32.5 42.136 74.636 8 Nasir 9 3249 Vandna Dev Anand Lohana Female 3/21/2002 BADIN 2020 924 84 A1 2294 65 32.5 42 74.5 10 2231 Sanjai Eshwar Kumar Luhano Male 8/17/2000 BADIN 2020 864 78.546 A 1939 70 35 39.273 74.273 RANA RAJINDAR 3771 RANA AMAR -

Tando Muhammad Khan

Tando Muhammad Khan 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010002 GBPS - YAR M. KANDRA@PIR BUX KANDRA Primary Boys 9,117 1,823 7,294 1,823 1,823 7,294 29,175 7,294 2 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010016 GBPS - YAR MUHAMMAD KANDRA Primary Boys 11,323 2,265 9,058 2,265 2,265 9,058 36,233 9,058 3 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010017 GBPS - KHUDA BUX GUMB Primary Boys 14,353 2,871 11,482 2,871 2,871 11,482 45,929 11,482 4 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010022 GBPS - ALAM KHAN TALPUR Primary Boys 44,542 8,908 35,634 8,908 8,908 35,634 142,535 35,634 5 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010025 GBPS - PALIO GHUMRANI Primary Boys 28,220 5,644 22,576 5,644 5,644 22,576 90,303 22,576 6 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. Khan 425010026 GBPS - KARIMABAD Primary Boys 28,690 5,738 22,952 5,738 5,738 22,952 91,808 22,952 7 Tando Muhammad Khan Tando Mohd Khan 1-UC-I Town T.M. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh

The Rise of Dalit Peasants Kolhi Activism in Lower Sindh (Original Thesis Title) Kolhi-peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Mahesar Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology ii Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Kolhi-Peasant Activism in Naon Dumbālo, Lower Sindh Creating Space for Marginalised through Multiple Channels Ghulam Hussain Thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, in partial fulfillment of the degree of ‗Master of Philosophy in Anthropology‘ iii Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan Year 2014 Formal declaration I hereby, declare that I have produced the present work by myself and without any aid other than those mentioned herein. Any ideas taken directly or indirectly from third party sources are indicated as such. This work has not been published or submitted to any other examination board in the same or a similar form. Islamabad, 25 March 2014 Mr. Ghulam Hussain Mahesar iv Final Approval of Thesis Quaid-i-Azam University Department of Anthropology Islamabad - Pakistan This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Mr. Ghulam Hussain. It is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant its acceptance by Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad for the award of the degree of ―MPhil in Anthropology‖. Committee Supervisor: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry External Examiner: Full name of external examiner incl. title Incharge: Dr. Waheed Iqbal Chaudhry v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This thesis is the product of cumulative effort of many teachers, scholars, and some institutions, that duly deserve to be acknowledged here. -

![[Jan-Mar.'2006] Awareness / Disclosure](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0740/jan-mar-2006-awareness-disclosure-680740.webp)

[Jan-Mar.'2006] Awareness / Disclosure

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized PREFACE The report in hand is the Final (updated October 2006) of the Integrated Social & Environmental Assessment (ISEA) for proposed Water Sector Improvement Project (WSIP). This report encompasses the research, investigations, analysis and conclusions of a study carried out by Mls Osmani & Co. (Pvt.) Ltd., Consulting Engineers for the Institutional Reforms Consultant (IRC) of Sindh Irrigation & Drainage Authority (SIDA). The Proposed Water Sector Improvement Project (WSIP) Phase-I, being negotiated between Government of Sindh and the World Bank entails a number of interventions aimed at improving the water management and institutional reforms in the province of Sindh. The second largest province in Pakistan, Sindh has approx. 5.0 Million Ha of farm area irrigated through three barrages and 14 canals. The canal command areas of Sindh are planned to be converted into 14 Area Water Boards (AWBs) whereby the management, operations and maintenance would be carried out by elected bodies. Similarly the distributaries and watercourses are to be managed by Farmers Organizations (FOs) and Watercourse Associations (WCAs), respectively. The Project focuses on the three established Area Water Boards (AWBs) of Nara, Left Bank (Akram Wah & Phuleli Canal) & Ghotki Feeder. The major project interventions include the following targets:- * Improvement of 9 main canals (726 Km) and 37 branch canals (1,441 Km). This includes new lining of 50% length of the lined reach of Akram Wah. * Control of Direct Outlets * Replacement of APMs with agreed type of modules * Improvement of 173 distributaries and minor canals ( 1527 Krn) including 145 Km of geomembrane lining and 1 12 Km of concrete lining in 3 AWBs. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Sectrarian Conflicts in Pakistan by Moonis Ahmar

Sectrarian Conflicts in Pakistan Moonis Ahmar Abstract The history of sectarian conflict in Pakistan is as old as the existence of this country. Yet, the intensification of sectarian divide in Pakistan was observed during late 1970s and early 1980s because of domestic political changes and the implications of Islamic revolution in Iran and the subsequent adverse reaction in some Arab countries to the assumption of power by clergy operating from the holy city of Qum. The military regime of General Mohammad Zia-ul-Haq, which seized power on July 5, 1977 pursued a policy of ‘Islamization’ resulting into the deepening of sectarian divide between Sunnis and Shiiates on the one hand and among different Sunni groups on the other. This paper attempts to analytically examine the dynamics of sectarian conflict in Pakistan by responding to following issues: The background of sectarian divide in Pakistan and how sectarian polarization between the Sunni and Shitte communities impacted on state and society; the phenomenon of religious extremism and intolerance led to the emergence of sectarian violence in Pakistan; the state of Pakistan failed to curb sectarian conflict and polarization at the societal level promoted the forces of religious extremism; the role of external factors in augmenting sectarian divide in Pakistan and foreign forces got a free hand to launch their proxy war in Pakistan on sectarian grounds; and strategies should be formulated to deal with the challenge of sectarian violence in Pakistan. 2 Pakistan Vision Vol. 9, No.1 1. Introduction Sectarian issue in Pakistan is a major destabilizing factor in the country’s political, social, religious and security order. -

Controlled Growth of Zinc Oxide Nanowire Arrays by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) Method

IJCSNS International Journal of Computer Science and Network Security, VOL.19 No.8, August 2019 135 Controlled Growth of Zinc Oxide Nanowire Arrays by Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) Method Waseem A. Bhutto1, Abdul Majid Soomro1, Altaf H. Nizamani1, Hussain Saleem2*, Murad Ali Khaskheli1, Ali Ghulam Sahito3, Roshan Das1, Usman Ali Khan1, Samina Saleem2,4 1Institute of Physics, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan. 2Department of Computer Science, UBIT, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan. 3Centre for Pure & Applied Geology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan. 4Karachi University Business School, KUBS, University of Karachi, Pakistan. *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract The Nanostructured materials like nanotubes, nanowires, sensors [11], Resistive-switching Random Access Memory nanorods, and nanobelts etc. have remained the subject of interest (RRAM) [12][13], nano-generators [14][15], nano- these days because of its unique thermal, mechanical and optical capacitors [16], and gas sensors [17][18]. properties. Zinc Oxide (푍푛푂), is the most attractive material due to its unique properties and availability of a variety of growth The performance of 푍푛푂 based devices strongly depend methods. At nanostructured level, the properties of 푍푛푂 can be on their dimensions and morphologies [19][20][21][22][23] altered by controlling the growth process, such as the shape, size, [24][25][26]. Therefore, the investigation of 푍푛푂 nano- morphology, aspect ratio and density control. In this work, structures in highly oriented, aligned and ordered arrays is of Aligned 푍푛푂 Nanowires (NWs) were successfully synthesized by critical importance for the development of novel devices. Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) on Aluminum doped Zinc Different methods have been used to synthesize 푍푛푂 Oxide (AZO) substrate. -

Sindhi Civil Society: Its Praxis in Rural Sindh, and Place in Pakistani Civil Society

Advances in Anthropology, 2014, 4, 149-163 Published Online August 2014 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/aa http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/aa.2014.43019 Sindhi Civil Society: Its Praxis in Rural Sindh, and Place in Pakistani Civil Society Ghulam Hussain1, Anwaar Mohyuddin1*, Shuja Ahmed2 1Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 2Pakistan Study Centre, University of Sindh, Jamshoro, Pakistan Email: [email protected], *[email protected] Received 26 June 2014; revised 24 July 2014; accepted 12 August 2014 Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Abstract Sindhi Civil Society and NGOs working in rural Sindh have a dialectical relationship with each oth- er and with rural communities, particularly peasants and marginalized rural ethnic groups. In this article, the nature and structure of Sindhi civil society vis-à-vis their efforts to differentiate them- selves from Pakistani civil society and ethnically hegemonic NGO-structuring, resultant perceived marginalization of Sindhi civil society and NGOs working in rural Sindh, have been classified, ex- plained and analyzed in the light of secondary and primary data. Effort has been made to locate historical intersection points between the spawning of NGOs and the origin of modern Civil Society networks, and relate it to Sindhi civil society in global perspective. This paper is the result of the analysis of secondary data validated through an ethnographic study conducted in Naon Dumbaalo and Chamber area of District Badin, and urban area of Qasimabad at Hyderabad District in Lower Sindh. -

In the High Court of Sindh, Karachi

[1] IN THE HIGH COURT OF SINDH, KARACHI C.P.No.D-2186 of 2021 Date Order with signature of Judge(s) Before: Mr. Justice Nazar Akbar Mr. Justice Muhammad Faisal Kamal Alam --------------------------------------------------------------------- Petitioner : Zabardast Khan Mahar, through Mr. Waqar Alam Abbasi, Advocate. Versus Respondent No.1 : The Federation of Pakistan Respondent No.2 : The Director General NAB, Sukkur. Date of Hearing : 05.04.2021 O R D E R NAZAR AKBAR, J:- The Petitioner has sought the following relief(s) through this petition: i. To reduce the surety amount to a reasonable and just sum to enunciate that the grant of bail is a form of relief and not a method of punishment as observed by the Hon'ble Supreme Court of Pakistan as well. ii Any other relief(s) which this Hon'ble Court deems fit and pr0per may kindly be granted. 2. On query from the Court, learned counsel for the Petitioner was unable to satisfy the Court that how an independent/fresh constitution petition can be filed when the Petitioner is aggrieved by an order passed by this very Bench in C.P No.D-1078/2020, whereby the said petition was disposed of. In the first place if the Petitioner was aggrieved by any observation, he should have filed petition for leave to appeal before Hon'ble Supreme Court. Additionally, this petition is not maintainable also for the following reasons: (i) This petition has not been signed and supported with the affidavit of the Petitioner. [2] (ii) Office objection No.7 that affidavit of Petitioner in support of petition is to be filed/sworn has not been properly answered by the Petitioner. -

Law and Order URC

Law and Order URC NEWSCLIPPINGS JANUARY TO JUNE 2019 LAW & ORDERS Urban Resource Centre A-2, 2nd floor, Westland Trade Centre, Block 7&8, C-5, Shaheed-e-Millat Road, Karachi. Tel: 021-4559317, Fax: 021-4387692, Email: [email protected], Website: www.urckarachi.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/URCKHI Twitter: https://twitter.com/urc_karachi 1 Law and Order URC Targeted killing: KMC employee shot dead in Hussainabad Unidentified assailants shot and killed an employee of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC) at Hussainabad locality of Federal B Area in Central district on Monday. The deceased was struck by seven bullets in different parts of the body. Nine bullet shells of a 9mm pistol were recovered from the scene of the crime. According to police, the deceased was called to the location through a phone call. They said the late KMC employee was on his motorcycle waiting for someone. Two unidentified men killed him by opening fire at him at Hussainabad, near Okhai Memon Masjid, in the limits of Azizabad police station. The deceased, identified as Shakeel Ahmed, aged 35, son of Shafiq Ahmed, was shifted to Abbasi Shaheed Hospital for medico-legal formalities. He was a resident of house no. L-72 Sector 5C 4, North Karachi, and worked as a clerk in KMC‘s engineering department. Rangers and police officials reached the scene after receiving information of the incident. They recovered nine bullet shells of a 9mm pistol and have begun investigating the incident. According to Azizabad DSP Shaukat Raza, someone had phoned and summoned the deceased to Hussainabad, near Okhai Memon Masjid.