Bird Conservation International Population and Spatial Breeding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES

Heritage Foundation’s DRR-COMPLIANT SUSTAINABLE CONSTRUCTION BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES DRR-DRIVEN POST-FLOOD REHABILITATION IN SINDH Introduction to Heritage Foundation eritage Foundation established in 1980 is a Pakistan- based, not-for-profit, social and cultural entrepreneur organization engaged in research, publication and Hconservation of Pakistan’s cultural heritage. The Foundation has been instrumental in saving a large num- ber of heritage treasures and, as UNESCO team leader 2003- 2005, undertook the stabilization of the endangered Shish Ma- hal ceiling of the 16th c. Lahore Fort World Heritage Site. The Foundation publishes monographs and documents relat- ing to heritage and history of Pakistan as well as guides for her- itage safeguarding aspects. It has published a series of invento- ries of historic assets as National Register of Historic Places of Pakistan. In the National Register series, in addition to several Karachi documents listing over 600 historic buildings, docu- ments covering parts of Peshawar, the Siran Valley, Hazara District and Azad Kashmir have been published. Since 2000, its outreach arm KaravanPakistan has involved communities and youth in heritage safeguarding activities. Since 2005, as part of Heritage for Rehabilitation and Devel- opment Program, in partnership with Nokia and Nokia Sie- mens Network, Heritage Foundation has carried out work of rehabilitation of communities, particularly women, affected by the Earthquake 2005 in Northern Pakistan. A 3-year pro- gram, suppported by Scottish Government Fund, Glasgow University and Scottish Pakistan Association on disaster risk resistance (DRR) focusing on women is currently being car- ried out in the Siran Valley. The establishment of KIRAT, Kar- avanPakistan Institute for Research and Training in 2008 has helped in carrying out research and training on varied aspect of sustainable construction techniques drawn from traditional materials and vernacular methods. -

The Jain History, Art and Architecture in Pakistan: a Fresh Light1

Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan Volume No. 56, Issue No. 1 (January - June, 2019) Muhammad Iqbal Chawla * Muhammad Hameed** Syeda Mahnaz Hassan *** The Jain History, Art and Architecture in Pakistan: A Fresh Light1 Abstract This paper attempts to understand the history, art and architecture of Jains in Pakistan with the new perspective. Among ancient religions of Indian Subcontinent, Jainism is the only one that remained a practicing religion in Pakistan till the country gained independence in 1947. Historical records clearly mention presence of jain community in major cities of Pakistan. Archaeological data consisting of jain temples, community halls and other shrines also throws light on the contribution of jains in the socio-religious, cultural, architectural and artistic activities of the country. Researches related to Indus Valley, Gandhara, Islamic and Hindu art and architecture have overshadowed the study of jain archaeology. Purpose of the present paper is to share what we intend to do regarding the study of Jainism in Pakistan. No major work has been done for the systematic exploration, identification and documentation of the jain built heritage of Pakistan. The Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab is taking this initiative for the first time to make detailed study of history of Jainism, its rise and decline. The study would highlight glory of the religion and contributions of its followers in social, cultural, economic, artistic and architectural fields. Comparative and analytical study of the jain archaeology would also be made keeping in view variety of the jain building traditions. Awareness among research scholars and local community would also be given to play their role for the preservation of Jain heritage scattered in different parts of Punjab as well as of Sindh province. -

Nagarparkar Drought- a Rapid Situation Appraisal and Intervention Identification

Nagarparkar drought- A Rapid situation appraisal and intervention identification By Pakistan Water Partnership Mission Dr. Pervaiz Amir, Economist (Mission Leader) Sheikh Muhammad Awais, Program Assistant/Finance Officer Zakir ullah Baig (project intern) Field support Hanif Khoso, Principle Luqman Shaheed Army Public School, Nagarparkar &Mubarik Rind April 2015 1 | P a g e Acknowledgments: Pakistan Water Partnership acknowledges the field assistance of Mr. Mubarik Rind and Mr. Muhammad Hanif Khoso exposing our team to drought issues of Nagarparkar. In particular Mr. Hanif who took out a Major Chunk of his time to deliberate and discuss challenges of Nagarparkar. We wish to acknowledge his input into this appraisal 2 | P a g e Table of Contents Purpose ............................................................................................................... 4 Background to Nagarparkar ................................................................................ 4 History Nagarparkar ............................................................................................ 4 Climate data: ....................................................................................................... 6 Agriculture .......................................................................................................... 7 Mission Observations .......................................................................................... 7 PWP Strategy for development activities in Nagarparkar. ................................. 14 Recommendations -

List of Dehs in Sindh

List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 1 Badin Badin 1 Abri 2 Badin Badin 2 Achh 3 Badin Badin 3 Achhro 4 Badin Badin 4 Akro 5 Badin Badin 5 Aminariro 6 Badin Badin 6 Andhalo 7 Badin Badin 7 Angri 8 Badin Badin 8 Babralo-under sea 9 Badin Badin 9 Badin 10 Badin Badin 10 Baghar 11 Badin Badin 11 Bagreji 12 Badin Badin 12 Bakho Khudi 13 Badin Badin 13 Bandho 14 Badin Badin 14 Bano 15 Badin Badin 15 Behdmi 16 Badin Badin 16 Bhambhki 17 Badin Badin 17 Bhaneri 18 Badin Badin 18 Bidhadi 19 Badin Badin 19 Bijoriro 20 Badin Badin 20 Bokhi 21 Badin Badin 21 Booharki 22 Badin Badin 22 Borandi 23 Badin Badin 23 Buxa 24 Badin Badin 24 Chandhadi 25 Badin Badin 25 Chanesri 26 Badin Badin 26 Charo 27 Badin Badin 27 Cheerandi 28 Badin Badin 28 Chhel 29 Badin Badin 29 Chobandi 30 Badin Badin 30 Chorhadi 31 Badin Badin 31 Chorhalo 32 Badin Badin 32 Daleji 33 Badin Badin 33 Dandhi 34 Badin Badin 34 Daphri 35 Badin Badin 35 Dasti 36 Badin Badin 36 Dhandh 37 Badin Badin 37 Dharan 38 Badin Badin 38 Dheenghar 39 Badin Badin 39 Doonghadi 40 Badin Badin 40 Gabarlo 41 Badin Badin 41 Gad 42 Badin Badin 42 Gagro 43 Badin Badin 43 Ghurbi Page 1 of 142 List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 44 Badin Badin 44 Githo 45 Badin Badin 45 Gujjo 46 Badin Badin 46 Gurho 47 Badin Badin 47 Jakhralo 48 Badin Badin 48 Jakhri 49 Badin Badin 49 janath 50 Badin Badin 50 Janjhli 51 Badin Badin 51 Janki 52 Badin Badin 52 Jhagri 53 Badin Badin 53 Jhalar 54 Badin Badin 54 Jhol khasi 55 Badin Badin 55 Jhurkandi 56 Badin Badin 56 Kadhan 57 Badin Badin 57 Kadi kazia -

Thar Coal Project and Local Community

Thar Coal Project and Local Community Documenting Views and Experiences of Stakeholders By Shujauddin Qureshi Zeenia Shaukat National Commission for Human Rights (NCHR) Contents Acronyms 1 Introduction and Rationale 2 Background 4 Thar Coal Background 5 The Tharparkar Context 7 Social Change in Thar 10 Thar Coal Project: A Brief Overview 14 Thar Coal and Environmental Concerns 16 Socioeconomic Issues 22 The Gorano Reservoir Issue 24 Summary of interview/discussion with community on December 14, 2018 30 Thar Coal Projects and Community’s Experiences 32 Broader concerns regarding the Project 36 Conclusion 44 Recommendations 46 Annexures 47 Acronyms Coal REAP Coal Resources Evaluation and Appraisal Programme COD Commercial Operation Date CPEC China-Pakistan Economic Corridor CPIH China Power International Holding Ltd CSR Corporate Social Responsibility EDS Effluent Disposal Scheme EIA Environmental Impact Assessment FGD Focused Group Discussion GOP Government of Pakistan GOS Government of Sindh GSP Geological Survey of Pakistan HRCP Human Rights Commission of Pakistan IEE Initial Environmental Examination IUCN International Union of Conservation of Nature LBOD Left Bank Outfall Drain MW Mega Watt MIPPs Mining & Independent Power Producers MNA Member of National Assembly NCHR National Commission for Human Rights NEQs National Environmental Quality Standards NSDWQ National Standards for Drinking Water Quality PPHI People's Primary Healthcare Initiative facilities RO Reverse Osmosis SAZDA Sindh Arid Zone Development Authority SECMC Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company SEPA Sindh Environment Protection Agency SHC Sindh High Court SSR Sino Sindh Resources (Pvt) Ltd TRDP Tharparkar Rural Development Programme USAID United States Agency for International Development pg. 1 Thar Coal Project and Local Community Introduction and Rationale Tharparkar is considered to be one of the underdeveloped districts of Pakistan. -

Petrology of Neoproterozoic Nagar Parkar Alkaline

69 Geol. Bull. Punjab Univ. 43, 2008. A-TYPE GRANITES FROM THE NAGARPARKAR COMPLEX, PAKISTAN: GEOCHEMISTRY AND ORIGIN BY SYED ALIM AHMAD Institute of Geology, University of the Punjab, Quaid-i-Azam Campus, Lahore-54590 Pakistan Email: [email protected] AND MOHAMMAD NAWAZ CHAUDHRY Postgraduate Centre for Earth Sciences, University of the Punjab, Quaid-e-Azam Campus, Lahore-54590, Pakistan Abstract: The Neoproterozoic Nagarparkar Complex is characterized by isolated semicircular hillocks of outcrops of “withinplate” A-type peralkaline to peraluminous granites. Geochemically the granites/rhyolites of the Nagarparkar Complex are characterized by high SiO2, Na2O+K2O, K2O, Fe/Mg, Al2O3, Zr, Nb and Y and low CaO and Sr. Majority of samples show moderate iron enrichment. The rocks show the characteristic trend of alkali enrichment and depletion of Ti, Fe, Mg and Ca, which are comparable with the rift-related mildly alkaline suites worldwide. Another characteristic feature of the alkaline/mildly alkaline felsic volcanoplutonics of the Nagarparkar area is their enrichment in incompatible trace elements similar to other peralkaline rocks of the Basin. High values of incompatible trace elements like Zr, Nb, Ce, and Y are characteristic of the granites/rhyolites under study. The multielement primitive mantle normalized spidergrams show that the granites/rhyolite from Nagarparkar Complex are enriched in Rb, Y, U and Zr, a characteristic of A-type granitoids. These granites are also strongly depleted in Ti and Sr. Negative Ti anomaly can be interpreted as reflecting ilmenite fractionation. Nb shows low negative anomaly, which is typical of crustal material. The negative anomaly shown by Ba and Sr can be attributed to low-pressure felspar fractionation and are typical of A-type granitoids. -

Post Monsoon Floristic Inventory of Nagarparkar, District Tharparkar, Sindh, Pakistan

Pure Appl. Biol., 8(1): 968-976, March, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.19045/bspab.2019.80038 Research Article Post monsoon floristic inventory of Nagarparkar, District Tharparkar, Sindh, Pakistan Mumtaz Ali Saand1, 2, Ameer Ahmed Mirbahar1, Naeema Khatoon Khaskheli2, Khalil Ahmed Ansari2, Shakeel Ahmed Khaskheli1, Muhammad Mahmood-ur-Rehman Jamro3 and Muzafar Hussain Sirohi2* 1. Centre for Conservation and Biodiversity (CBC), Shah Abdul Latif University Khairpur-Pakistan 2. Department of Botany, Shah Abdul Latif University Khairpur-Pakistan 3. AZRI field station Khairpur, Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC)-Pakistan *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected] Citation Mumtaz Ali Saand, Ameer Ahmed Mirbahar, Naeema Khatoon Khaskheli, Khalil Ahmed Ansari, Shakeel Ahmed Khaskheli, Muhammad Mahmood-ur-Rehman Jamro and Muzafar Hussain Sirohi. Post monsoon floristic inventory of Nagarparkar, District Tharkarpar, Sindh, Pakistan. Pure and Applied Biology. Vol. 8, Issue 1, pp968-976. http://dx.doi.org/10.19045/bspab.2019.80038 Received: 12/12/2018 Revised: 07/03/2019 Accepted: 11/03/2019 Online First: 27/03/2019 Abstract The monsoon rain brings a green carpet of landscape to Thar Desert including Karoonjhar mountains range. We explored Nagarparkar, District Tharparkar, Sindh to record post monsoon botanical inventory of the region. The study confirmed 89 plant species of 26 plant families. The vegetation was dominated by Poaceae (18 spp.) and Fabaceae (15 spp.) families. About two third of the families were represented by single species. The vegetation was rich with grasses and herbs making about 60% of the species while the rest includes tress shrubs and subshrubs. The lifespan analysis revealed the dominance of perennials. -

Land Covers Change Assessment After Small Dam's Construction

Available online at www.CivileJournal.org Civil Engineering Journal Vol. 5, No. 4, April, 2019 Land Covers Change Assessment After Small Dam’s Construction Based on the Satellite Data Nabi Bux Bhatti a*, Altaf Ali Siyal a, Abdul Latif Qureshi a, Imtiaz Ali Bhatti b a U.S. -Pakistan Center for Advanced Studies in Water (U.S-PCAS-W), Mehran University of Engineering and Technology, Jamshoro, 76062, Pakistan. b Faculty of Civil and Environmental Engineering University Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia Parit Raja, Johor, 86400, Malaysia. Received 28 December 2018; Accepted 08 March 2019 Abstract The small dams were constructed in the study area for storing the rainwater. The present study was conducted to assess the impact of small dams on the LCC (Land Cover Change) in Nangarparkar, Pakistan based on the satellite data. The ENVI (Environment for Visualizing Images) software was used for classification of the four year’s images and three classes viz. water, vegetation, and soil were taken for detection of LCC. The MLH (Maximum Likelihood) supervised method was used to classify the multispectral satellite images. The classified results of the classes were found different each year before and after dam construction. Average results of the two years before dam’s construction revealed that water availability, vegetation cover and soil cover was 3.02%, 18.52%, and 32.30% respectively. However, after the dam construction, the water availability, vegetation cover and soil cover was 8.49%, 34.33%, and 17.15% respectively. Overall results revealed that water availability and vegetation cover were increased by 5.47 % and 15.18% respectively while soil cover decreased 15.15% after the construction of dams. -

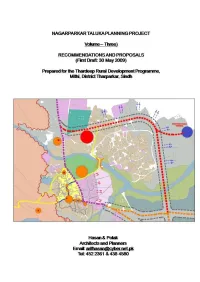

Nagarparkar Taluka Planning Project Which Has Been Initiated by Thardeep Rural Development Programme (TRDP)

CONTENTS Introduction 1. Background 1.1 Origins of the Project 1.2 TRDP’s Initiatives 1.3 Visits and Discussions 1.4 Final Work Plan for Phase One 1.5 Maps of Thar District and Nagarparkar Taluka 1.6 Some Examples for Maps Made for Phase One 2. Findings, Recommendations and Possible Projects 2.1 Nagarparkar Taluka 2.1.1 Summary of findings 2.1.2 Recommendations 2.1.3 Scenic spots along with the major road corridors in the Taluka 2.2 Nagarparkar Town 2.2.1 Summary of findings 2.2.2 Recommendations 2.2.3 Projects that come out of the recommendations 2.2.4 Maps and photographs of Nagarparkar Town 2.3 Virawah Village 2.3.1 Summary of findings 2.3.2 Recommendations 2.3.3 Projects that come out of the recommendations 2.3.4 Maps and photographs for Virawah 2.4 Bodisar Village 2.4.1 Summary of findings 2.4.2 Recommendations 2.4.3 Projects that come out of the recommendations 2.4.4 Maps and photographs for Bodisar 2.5 Kasbo Village 2.5.1 Summary of findings 2.5.2 Recommendations 2.5.3 Projects that come out of the recommendations 2.5.4 Maps and photographs of Kasbo 2 2.6 Ghori Village 2.6.1 Summary of findings 2.6.2 Recommendations for projects 2.3.3 Plan of Ghori Village access road to the temple and location of proposed facilities 2.7 Churio Village 2.7.1 Summary of findings 2.7.2 Recommendations and projects 2.3.3 Maps and photographs 3. -

Proposal for Qurbani 2020SINDH

PROPOSAL FOR QURBANI PROJECT FOR THE YEAR 2020 AT SINDH & QUETTA CITY We are trying our level best to do Qurbani better than last year so, the people they could not get meat in all over the year they could get meat the better way. With the cooperation of Saviour USA people of backward area could eat and get meat in as per their requirement. So we made five zones (including Sindh & Quetta City) a headquarter will also be arranged where all the arrangements will took place, headquarter will distributed all the meat to five zones mentioned here. ZONE-1 (THARPARKAR) SINDH Sr No. Village Name 1. Islam Kot City 2. Diplo City 3. Mitthi City 4. Naukot City 5. Chachro City 6. Village Ratanyari, Tehsil Nagarparkar Tharparkar 7. Village Bhalwah, Tehsil Nagarparkar Tharparkar 8. Village Danodandal, Tehsil Nagarparkar Tharparkar 9. Village Chanesar ki Dhani, Tehsil Nagarparkar Tharparkar 10. Village Abdul Ghafoor ki Dhani, Tehsil Nagarparkar Tharparkar 11. Village Katal, Tehsil Islamkot Tharparkar 12. Village Adam Tarr, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 13. Village Shadi Rind, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 14. Village Khan Muhammad Rind, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 15. Village Mirzoo Khan Rind, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 16. Village Sawan ki Dhani, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 17. Village Ahmed Tarr, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 18. Village Rakhio ki Dhani, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 19. Village Rajoro, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 20. Village Mubarak Rind, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 21. Village Chandio Goth, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh 22 Village Karim Dad Tarr, Tehsil Chachro Tharparkar Sindh ZONE-2 (DADU) SINDH Sr No. -

The Indian Wild

THE INDIAN WILD ASS A Survey—February, 1962 Prepared for the Survival Service Commission of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources By E. P. GEE I. INTRODUCTION Information on the present population and status of the Indian Wild Ass Equus hemionus khur Lesson, 1827, is scanty. For this reason I was prompted to undertake this brief fact-finding survey, especially as South African Horse Sickness 1 had been reported in that part of India recently. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources sponsored my expedition, and the World Wildlife Fund very kindly paid my travelling expenses from the eastern part of India to the furthest western tip of the country. The Report deals with the Indian Wild Ass. There are altogether in Asia five subspecies of Equus hemionus listed by Ellerman and Morrison- Scott (1951) :— " Equus hemionus hemionus Pallas, 1775. Mongolian Wild Ass. Range : now apparently only found about Orok Nor, in Central Mongolia. " Equus hemionus onager Boddaert, 1785. Persian Onager. Range : north-eastern parts of Persia and North-Western Afganistan ; Russian Turkestan, as above. " Equus hemionus khur Lesson, 1827. Indian Wild Ass or Ghor-khar. Range : The Rann of Cutch, possibly Baluchistan, and South-Eastern Persia. "Equus hemionus kiang Moorcroft, 1841. Kiang. Range: Ladak, Nepal, SikkLm, Tibet to Kukunor district. " Equus hemionus hemippus I., Geoffroy, 1885. Range : Syrian Desert and adjacent parts. Possibly now extinct." The last mentioned is the Syrian Wild Ass which is considered by Talbot (1960) to be extinct. (Of the wild asses of Egypt Talbot (1960) states " The wild ass was once found over much of the Eastern Desert, occasionally ranging further west along the Sudan border. -

Nagar Parker Diplo Islamkot Mithi Dahli Chachro Drought

Drought Hit in Thar Legend Outbreak of Waterborne Diseases (as of Feb 14, 2016) G Basic Health Unit 190 children die after outbreak Government & Private Health Facility ÷Ó Children Hospital of disease in drought-hit Thar Health Facility Government Private Total More than ailing children, meanwhile, have been Sanghar Basic Health Unit 21 0 21 G Dispensary admitted to different hospitals in the drought-hit Thar district Children Hospital 0 1 1 "' Dispensary 12 0 12 District Headquarter Hospital Hospitals are facing a shortage of doctors. Only 298 doctors District Headquarter Hospital 1 0 1 ÷Ó Family Welfare Centre are available, which includes child specialists and female Family Welfare Center 3 0 3 doctors. Meanwhile, over 215 dispensaries remain General Hospitals 1 3 4 K" General Hospital non-functional in Thar's remote villages General Physician 0 14 14 G MITHI: The ongoing human tragedy of deaths of children in Thar shows no signs of abating, despite Maternity Home 0 3 3 General Physician tall claims by the government that it has provided the best healthcare facilities, as eight more babies died of malnutrition and waterborne diseases over the past two days.Four children died on Saturday Medical Stores 0 2 2 Õ Medical Stores and as many died a day before. Of them, a six-month-old baby Kavita and two other newborn babies Rural Health Center 3 0 3 "' died at the Mithi Civil Hospital and five-month-old Pirbhu died at rural health centre in Islamkot on Specialist 0 1 1 Rural Health Centre Saturday.On Friday, a minor girl Rasheeda who was