The Far Right, Punk and British Youth Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Internal Brakes the British Extreme Right (Pdf

FEBRUARY 2019 The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation The British extreme right in the 1990s ANNEX B Joel Busher, Coventry University Donald Holbrook, University College London Graham Macklin, Oslo University This report is the second empirical case study, produced out of The Internal Brakes on Violent Escalation: A Descriptive Typology programme, funded by CREST. You can read the other two case studies; The Trans-national and British Islamist Extremist Groups and The Animal Liberation Movement, plus the full report at: https://crestresearch.ac.uk/news/internal- brakes-violent-escalation-a-descriptive-typology/ To find out more information about this programme, and to see other outputs from the team, visit the CREST website at: www.crestresearch.ac.uk/projects/internal-brakes-violent-escalation/ About CREST The Centre for Research and Evidence on Security Threats (CREST) is a national hub for understanding, countering and mitigating security threats. It is an independent centre, commissioned by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and funded in part by the UK security and intelligence agencies (ESRC Award: ES/N009614/1). www.crestresearch.ac.uk ©2019 CREST Creative Commons 4.0 BY-NC-SA licence. www.crestresearch.ac.uk/copyright TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................5 2. INTERNAL BRAKES ON VIOLENCE WITHIN THE BRITISH EXTREME RIGHT .................10 2.1 BRAKE 1: STRATEGIC LOGIC .......................................................................................................................................10 -

White Noise Music - an International Affair

WHITE NOISE MUSIC - AN INTERNATIONAL AFFAIR By Ms. Heléne Lööw, Ph.D, National Council of Crime Prevention, Sweden Content Abstract............................................................................................................................................1 Screwdriver and Ian Stuart Donaldson............................................................................................1 From Speaker to Rock Star – White Noise Music ..........................................................................3 Ideology and music - the ideology of the white power world seen through the music...................4 Zionist Occupational Government (ZOG).......................................................................................4 Heroes and martyrs........................................................................................................................12 The Swedish White Noise Scene...................................................................................................13 Legal aspects .................................................................................................................................15 Summary........................................................................................................................................16 Abstract Every revolutionary movement has its own music, lyrics and poets. The music in itself does not create organisations nor does the musicians themselves necessarily lead the revolution. But the revolutionary/protest music create dreams, -

Transnational Neo-Nazism in the Usa, United Kingdom and Australia

TRANSNATIONAL NEO-NAZISM IN THE USA, UNITED KINGDOM AND AUSTRALIA PAUL JACKSON February 2020 JACKSON | PROGRAM ON EXTREMISM About the Program on About the Author Extremism Dr Paul Jackson is a historian of twentieth century and contemporary history, and his main teaching The Program on Extremism at George and research interests focus on understanding the Washington University provides impact of radical and extreme ideologies on wider analysis on issues related to violent and societies. Dr. Jackson’s research currently focuses non-violent extremism. The Program on the dynamics of neo-Nazi, and other, extreme spearheads innovative and thoughtful right ideologies, in Britain and Europe in the post- academic inquiry, producing empirical war period. He is also interested in researching the work that strengthens extremism longer history of radical ideologies and cultures in research as a distinct field of study. The Britain too, especially those linked in some way to Program aims to develop pragmatic the extreme right. policy solutions that resonate with Dr. Jackson’s teaching engages with wider themes policymakers, civic leaders, and the related to the history of fascism, genocide, general public. totalitarian politics and revolutionary ideologies. Dr. Jackson teaches modules on the Holocaust, as well as the history of Communism and fascism. Dr. Jackson regularly writes for the magazine Searchlight on issues related to contemporary extreme right politics. He is a co-editor of the Wiley- Blackwell journal Religion Compass: Modern Ideologies and Faith. Dr. Jackson is also the Editor of the Bloomsbury book series A Modern History of Politics and Violence. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author, and not necessarily those of the Program on Extremism or the George Washington University. -

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: Lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet Alexander B. Stohler FacultyAdviser: Dr, Dennis Klein r'^dw May 13,2020 )ol, Masters of Arts in Holocaust & Genocide Studies Kean University In partialfulfillumt of the rcquirementfar the degee of Moster of A* Abstract: I focused my research on modern, American hate groups. I found some criteria for early- warning signs of antisemitic, bigoted and genocidal activities. I included a summary of neo-Nazi and white supremacy groups in modern American and then moved to a more specific focus on contemporary and prominent groups like Atomwaffen Division, the Proud Boys, the Vinlanders Social Club, the Base, Rise Against Movement, the Hammerskins, and other prominent antisemitic and hate-driven groups. Trends of hate-speech, acts of vandalism and acts of violence within the past fifty years were examined. Also, how law enforcement and the legal system has responded to these activities has been included as well. The different methods these groups use for indoctrination of younger generations has been an important aspect of my research: the consistent use of hate-rock and how hate-groups have co-opted punk and hardcore music to further their ideology. Live-music concerts and festivals surrounding these types of bands and how hate-groups have used music as a means to fund their more violent activities have been crucial components of my research as well. The use of other forms of music and the reactions of non-hate-based artists are also included. The use of the internet, social media and other digital means has also be a primary point of discussion. -

Identifying Extreme Racist Beliefs

identifying extreme racist beliefs What to look out for and what to do if you see any extreme right wing beliefs promoted in your neighbourhood. At Irwell Valley Homes, we believe that everyone has the If you see any of these in any of the neighbourhoods right to live of life free from racism and we serve, please contact us straight away on 0300 discrimination. However, whilst we work to promote 561 1111 or [email protected]. We take equality, racism still exists and we want to take action to this extremely seriously and will work with the Greater stop this. Manchester Police to deal with anyone responsible. This guide helps you to identify some of the numbers, signs and symbols used to promote extreme right wing beliefs including racism, extreme nationalism, fascism and neo nazism. 18: The first letter of the alphabet is A; the eighth letter of the alphabet is H. so, 1 plus 8, or 18, equals AH, an abbreviation for Adolf Hitler. Neo-Nazis use 18 in tat- toos and symbols. The number is also used by Combat 18, a violent British neo-Na- zi group that chose its name in honour of Adolf Hitler. 14: This numeral represents the phrase “14 words,” the number of words in an ex- pression that has become the slogan for the white supremacist movement. 28: The number stands for the name “Blood & Honour” because B is the 2nd letter of the alphabet and H is the 8th letter. Blood & Honour is an international neo-Nazi/ racist skinhead group started by British white supremacist and singer Ian Stuart. -

Trouser Press

ARTIST TITLE SECTION ISSUE A Band America Underground 50 ABBA article 45 incl (power pop) 27 Voulez-Vous Hit and Run 42 Super Trouper Hit and Run 59 The Visitors Hit and Run 71 ABC article 82, 96 Lexicon of Love 78 Beauty Stab 95 Fax n Rumours 90 Green Circles 72, 75, 78 A Blind Dog Stares America Underground 75 Mick Abrahams incl 11 Abwarts Der Westen Ist Einsam 77 incl (Germany) 78 Accelerators America Underground 44 AC/DC article 23, 57 incl 16, 17, 63 High Voltage 17 Powerage 32 Highway to Hell Hit and Run 43 Back in Black 56 For Those About to Rock Hit and Run 71 Fax n Rumours 50 A Certain Ratio The Graveyard and the Ballroom 60 To Each… 65 Sextet 75 I’d Like to See You Hit and Run 85 Green Circles 65 Acid Casualties Panic Station Hit and Run 79 Acrylix America Underground 84 Act Too Late at 20 Hit and Run 72 Action America Underground 34, 48 Green Circles 82 Action Faction America Underground 92 Action Memos America Underground 80 Actor America Underground 41 Actuel America Underground 87 Adam and the Ants cover story 69 article 63 family tree 65 live 64 Green Circles 65, 68 Kings of the Wild Frontier 60 Prince Charming 70 Fax n Rumours 62 See also Adam Ant Andy Adams One of the Boys Hit and Run 51 Bryan Adams Bryan Adams Hit and Run 50 You Want It, You Got It Hit and Run 67 King Sunny Adé live 92 Juju Music 80 Synchro System 91 Surface Noise 80 Adicts Green Circles 82 AD 1984 Green Circles 47 Adolescents America Underground 66 Adults America Underground 86 Advertising Jingles 32 Green Circles 27, 31 Adverts incl 55 Crossing the -

Loud Proud Passion and Politics in the English Defence League Makes Us Confront the Complexities of Anti-Islamist/Anti-Muslim Fervor

New Ethnographies ‘These voices of English nationalism make for difficult listening. The great strength of Hilary PILKINGTON Pilkington’s unflinching ethnography is her capacity to confound and challenge our political and preconceptions and makes us think harder. This is an important, difficult and brave book.’ Les Back, Professor of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London ‘Pilkington offers fresh and crucial insights into the politics of fear. Her unflinchingly honest depiction of the EDL breaks apart stereotypes of rightist activists as simply dupes, thugs, and racists and Loud proud PASSION AND POLITICS IN THE ENGLISH DEFENCE LEAGUE makes us confront the complexities of anti-Islamist/anti-Muslim fervor. This terrific, compelling book is a must-read for scholars and readers concerned about the global rise of populist movements on the right.’ Kathleen Blee, Distinguished Professor of Sociology, University of Pittsburgh Loud and proud uses interviews, informal conversations and extended observation at English Defence League events to critically reflect on the gap between the movement’s public image and activists’ own understandings of it. It details how activists construct the EDL and themselves as ‘not racist, not violent, just no longer silent’ through, among other things, the exclusion of Muslims as a possible object of racism on the grounds that they are a religiously not racially defined Loud group. In contrast, activists perceive themselves to be ‘second-class citizens’, disadvantaged and discriminated against by a two-tier justice system that privileges the rights of others. This failure to recognise themselves as a privileged white majority explains why ostensibly intimidating EDL street demonstrations marked by racist chanting and nationalistic flag waving are understood by activists as standing ‘loud and proud’; the only way of being heard in a political system governed by a politics of silencing. -

Dreaming of a National Socialist World: the World Union of National Socialists (Wuns) and the Recurring Vision of Transnational Neo-Nazism

fascism 8 (2019) 275-306 brill.com/fasc Dreaming of a National Socialist World: The World Union of National Socialists (wuns) and the Recurring Vision of Transnational Neo-Nazism Paul Jackson Senior Lecturer in History, University of Northampton [email protected] Abstract This article will survey the transnational dynamics of the World Union of National Socialists (wuns), from its foundation in 1962 to the present day. It will examine a wide range of materials generated by the organisation, including its foundational docu- ment, the Cotswolds Declaration, as well as membership application details, wuns bulletins, related magazines such as Stormtrooper, and its intellectual journals, Nation- al Socialist World and The National Socialist. By analysing material from affiliated organisations, it will also consider how the network was able to foster contrasting rela- tionships with sympathetic groups in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Europe, al- lowing other leading neo-Nazis, such as Colin Jordan, to develop a wider role interna- tionally. The author argues that the neo-Nazi network reached its height in the mid to late 1960s, and also highlights how, in more recent times, the wuns has taken on a new role as an evocative ‘story’ in neo-Nazi history. This process of ‘accumulative extrem- ism’, inventing a new tradition within the neo-Nazi movement, is important to recog- nise, as it helps us understand the self-mythologizing nature of neo-Nazi and wider neo-fascist cultures. Therefore, despite failing in its ambitions of creating a Nazi- inspired new global order, the lasting significance of the wuns has been its ability to inspire newer transnational aspirations among neo-Nazis and neo-fascists. -

Historia Del Oi

Historia del oi Por: V. Marchi Tomado de: "Skin and Red" Esta es la historia del Oi!, el movimiento juvenil mas odiado, explotado e incomprendido de nuestro tiempo: asi comienza "The Story of Oi!", de Garry Johnson, uno de los analisis mas lucidos y apropiados jamas publicados del Oi! Movement. Por que "odiado, explotado e incomprendido"? Porque, como ya había sucedido con Sham 69 en los annos 1978-79, grupos ciertamente no fascistas aun venian siendo seguidos por sectores juveniles simpatizantes del National Front y de otras organizaciones neofascistas britanicas. Pero, al contrario de lo que había pasado con el real punk, que ciertamente no habia sido considerado por esto un movimiento de extrema derecha, el Oi! se halla al centro de una verdadera campanna de desinformacion, que acabara por sepultarlo bajo la infame etiqueta de "musica para nazis". Paradojicamente, en el curso de los annos de oro del Oi! -mas o menos de 1980 a 1982- la presencia fascista en los conciertos estaba fuertemente disminuida en relacion con los tiempos de Sham 69: pero esta es la vida real, y aquí hablamos de otra cosa Por que, nos preguntamos, tanto encarnizamiento contra este particular filon del punk, esta escena en la cual skinheads punkizados y punks skinheadizados gritan la propia rabia frecuentemente apolitica, aun mas frecuentemente provocadora, siempre gozosamente plebeya? Porque -responde Johnson- el Oi! es demasiado real para "ellos". Los espanta porque no pueden transformarlo en un suplemento del "Sunday", botarlo a la basura El Oi! es lo que el punk era en sus inicios: la musica de la clase obrera tocada por grupos de la clase obrera para jovenes de la clase obrera recordar la "voz del 78": No Seguir a Ningun Lider!. -

The Barriers Come Down: Antisemitism and Coalitions of Extremes in the Uk Anti-War Movement

THE BARRIERS COME DOWN: ANTISEMITISM AND COALITIONS OF EXTREMES By Dave Rich These are strange times for the British far right. Long left alone on the political extremes where they obsessed about secret Jewish machinations behind every government policy, all of a sudden they think they have noticed the most unlikely people agreeing with them. The British National Party advised its members to read The Guardian for information about “the Zionist cabal around President Bush1”. Followers of the neo-Nazi Combat 18 have found themselves publicly supporting the President of Malaysia, Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, while the National Front found itself in sympathy with Labour MP Tam Dalyell. No wonder John Tyndall, former leader of the British National Party, wrote gleefully that “certain things are coming out into the open which not long ago would have been tightly censored and suppressed…We are witnessing a gigantic conspiracy being unveiled2”. But are the antisemites of Britain’s far right correct in thinking that their view of a Jewish-controlled world is becoming accepted across the political spectrum? This excitement amongst Britain’s neo-Nazis has been fuelled by the widespread theory that the war in Iraq was devised and executed by pro-Israeli, mainly Jewish, neo-conservative lobbyists in Washington D.C.; that this is only one example of how American foreign policy has been hijacked by a Jewish or Zionist cabal; and that these neo-cons are pro-Israeli to the point that they did this not for the good of America, but purely for the interests of Israel and, by extension, Jews. -

Angry Aryans Bound for Glory in a Racial Holy War: Productions of White Identity in Contemporary Hatecore Lyrics

Angry Aryans Bound for Glory in a Racial Holy War: Productions of White Identity in Contemporary Hatecore Lyrics Thesis Presented in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Roberto Fernandez Morales, B.A. Graduate Program in Sociology The Ohio State University 2017 Thesis Committee: Vincent Roscigno, Advisor Hollie Nyseth Brehm Eric Schoon Copyright by Roberto Fernandez Morales 2017 Abstract The Southern Poverty Law Center reports that, over the last 20 years, there has been a steady rise in hate groups. These groups range from alternative right, Neo Confederates, White Supremacist to Odinist prison gangs and anti-Muslim groups. These White Power groups have a particular race-based ideology that can be understood relative to their music—a tool that provides central recruitment and cohesive mechanisms. White supremacist rock, called Hatecore, presents the contemporary version of the legacy of racist music such as Oi! and Rock Against Communism. Through the years, this genre produces an idealized model of white supremacist, while also speaking out against the perceived threats, goals, and attitudes within white supremacist spaces. In this thesis, I use content analysis techniques to attempt to answer two main questions. The first is: What is the ideal type of white supremacist that is explicitly produced in Hatecore music? Secondly, what are the concerns of these bands as they try to frame these within white supremacist spaces? Results show that white supremacist men are lauded as violent and racist, while women must be servile to them. Finally, white supremacist concerns are similar to previous research, but highlight growing hatred toward Islam and Asians. -

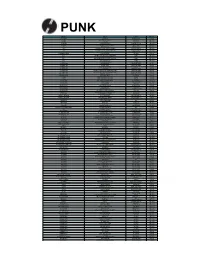

Order Form Full

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS