Bartonella Henselae Bloodstream Infection in a Boy with Pediatric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Diversity of Bartonella Species in Small Mammals in the Qaidam

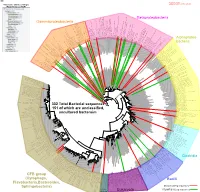

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Genetic diversity of Bartonella species in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China Huaxiang Rao1, Shoujiang Li3, Liang Lu4, Rong Wang3, Xiuping Song4, Kai Sun5, Yan Shi3, Dongmei Li4* & Juan Yu2* Investigation of the prevalence and diversity of Bartonella infections in small mammals in the Qaidam Basin, western China, could provide a scientifc basis for the control and prevention of Bartonella infections in humans. Accordingly, in this study, small mammals were captured using snap traps in Wulan County and Ge’ermu City, Qaidam Basin, China. Spleen and brain tissues were collected and cultured to isolate Bartonella strains. The suspected positive colonies were detected with polymerase chain reaction amplifcation and sequencing of gltA, ftsZ, RNA polymerase beta subunit (rpoB) and ribC genes. Among 101 small mammals, 39 were positive for Bartonella, with the infection rate of 38.61%. The infection rate in diferent tissues (spleens and brains) (χ2 = 0.112, P = 0.738) and gender (χ2 = 1.927, P = 0.165) of small mammals did not have statistical diference, but that in diferent habitats had statistical diference (χ2 = 10.361, P = 0.016). Through genetic evolution analysis, 40 Bartonella strains were identifed (two diferent Bartonella species were detected in one small mammal), including B. grahamii (30), B. jaculi (3), B. krasnovii (3) and Candidatus B. gerbillinarum (4), which showed rodent-specifc characteristics. B. grahamii was the dominant epidemic strain (accounted for 75.0%). Furthermore, phylogenetic analysis showed that B. grahamii in the Qaidam Basin, might be close to the strains isolated from Japan and China. -

Bartonella Henselae • Fleas and Black-Legged Ticks (Also Called Deer Ticks) of the Genus Ixodes May Serve As Vectors, but This Has Not Disease Agent: Been Proven

APPENDIX 2 Bartonella henselae • Fleas and black-legged ticks (also called deer ticks) of the genus Ixodes may serve as vectors, but this has not Disease Agent: been proven. • Bartonella henselae Blood Phase: Disease Agent Characteristics: • Agent found in endothelial cells and associated with RBCs in symptomatic cases • Gram-negative bacillus or coccobacillus, aerobic, • Occult bacteremia sometimes occurs in the absence nonmotile, nonspore-forming, facultatively intracel- of specific antibodies. lular bacterium • Order: Rhizobiales; Family: Bartonellaceae Survival/Persistence in Blood Products: • Size: 0.3-0.6 ¥ 0.3-1.0 mm • Nucleic acid: Approximately 1900 kb of DNA • A spiking study suggests that B. henselae added to RBCs can be recovered on solid media through 35 Disease Name: days of storage at 4°C. • Cat scratch disease • Cat scratch fever Transmission by Blood Transfusion: • Bacillary angiomatosis • Theoretical • Bacillary peliosis Cases/Frequency in Population: Priority Level: • 22,000 cases per year estimated in the US • Scientific/Epidemiologic evidence regarding blood • 2-6% in US blood donors safety: Theoretical • Cumulative seroprevalence of 7.1% to B. henselae and • Public perception and/or regulatory concern regard- B. quintana in US veterinary professionals ing blood safety: Absent • Public concern regarding disease agent: Very low Incubation Period: Background: • 3-10 days to appearance of papule at inoculation site; regional adenopathy may follow after a few weeks • In 1909,ALBartondescribed organisms that adhered to RBCs. Likelihood of Clinical Disease: • The name Bartonella bacilliformis was used for the • Relatively benign and self-limiting, lasting 6-12 weeks only member of the group identified before 1993. in the absence of antibiotic therapy • Several other species of Bartonella are known to infect humans, but at present, B. -

Bartonella Henselae Detected in Malignant Melanoma, a Preliminary Study

pathogens Article Bartonella henselae Detected in Malignant Melanoma, a Preliminary Study Marna E. Ericson 1, Edward B. Breitschwerdt 2 , Paul Reicherter 3, Cole Maxwell 4, Ricardo G. Maggi 2, Richard G. Melvin 5 , Azar H. Maluki 4,6 , Julie M. Bradley 2, Jennifer C. Miller 7, Glenn E. Simmons, Jr. 5 , Jamie Dencklau 4, Keaton Joppru 5, Jack Peterson 4, Will Bae 4, Janet Scanlon 4 and Lynne T. Bemis 5,* 1 T Lab Inc., 910 Clopper Road, Suite 220S, Gaithersburg, MD 20878, USA; [email protected] 2 Intracellular Pathogens Research Laboratory, Comparative Medicine Institute, College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27607, USA; [email protected] (E.B.B.); [email protected] (R.G.M.); [email protected] (J.M.B.) 3 Dermatology Clinic, Truman Medical Center, University of Missouri, Kansas City, MO 64108, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Dermatology, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (A.H.M.); [email protected] (J.D.); [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (W.B.); [email protected] (J.S.) 5 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Duluth Campus, Medical School, University of Minnesota, Duluth, MN 55812, USA; [email protected] (R.G.M.); [email protected] (G.E.S.J.); [email protected] (K.J.) 6 Department of Dermatology, College of Medicine, University of Kufa, Kufa 54003, Iraq 7 Galaxy Diagnostics Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC 27709, USA; [email protected] Citation: Ericson, M.E.; * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-720-560-0278; Fax: +1-218-726-7906 Breitschwerdt, E.B.; Reicherter, P.; Maxwell, C.; Maggi, R.G.; Melvin, Abstract: Bartonella bacilliformis (B. -

Bacteria Clostridia Bacilli Eukaryota CFB Group

AM935842.1.1361 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY283260.1.1552 Alcaligenes sp. PCNB−2 Class Betaproteobacteria AM934953.1.1374 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581593.1.1460 uncultured betaAM936569.1.1351 proteobacterium uncultured Class Betaproteobacteria Derxia sp. Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581621.1.1418 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ248272.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium soil uncultured DQ248272.1.1498 DQ248235.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium RS49 DQ248270.1.1496 uncultured soil bacterium DQ256489.1.1211 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax DQ256489.1.1211 AF523053.1.1486 uncultured Comamonadaceae bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY706442.1.1396 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY706442.1.1396 AJ536763.1.1422 uncultured bacterium CS000359.1.1530 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax CS000359.1.1530 AY168733.1.1411 uncultured bacterium AJ009470.1.1526 uncultured bacterium SJA−62 Class Betaproteobacteria Class SJA−62 bacterium uncultured AJ009470.1.1526 AY212561.1.1433 uncultured bacterium D16212.1.1457 Rhodoferax fermentans Class Betaproteobacteria Class fermentans Rhodoferax D16212.1.1457 AY957894.1.1546 uncultured bacterium AJ581620.1.1452 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria RS76 AY625146.1.1498 uncultured bacterium RS65 DQ316832.1.1269 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ404909.1.1513 uncultured bacterium uncultured DQ404909.1.1513 AB021341.1.1466 bacterium rM6 AJ487020.1.1500 uncultured bacterium uncultured AJ487020.1.1500 RS7 RS86RC AF364862.1.1425 bacterium BA128 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957931.1.1529 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957931.1.1529 CP000884.723807.725332 Delftia acidovorans SPH−1 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957923.1.1520 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957923.1.1520 RS18 AY957918.1.1527 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957918.1.1527 AY945883.1.1500 uncultured bacterium AF526940.1.1489 uncultured Ralstonia sp. -

Isolation of Francisella Tularensis from Skin Ulcer After a Tick Bite, Austria, 2020

microorganisms Case Report Isolation of Francisella tularensis from Skin Ulcer after a Tick Bite, Austria, 2020 Mateusz Markowicz 1,*, Anna-Margarita Schötta 1 , Freya Penatzer 2, Christoph Matscheko 2, Gerold Stanek 1, Hannes Stockinger 1 and Josef Riedler 2 1 Center for Pathophysiology, Infectiology and Immunology, Institute for Hygiene and Applied Immunology, Medical University of Vienna, Kinderspitalgasse 15, A-1090 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] (A.-M.S.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (H.S.) 2 Kardinal Schwarzenberg Klinikum, Kardinal Schwarzenbergplatz 1, A-5620 Schwarzach, Austria; [email protected] (F.P.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (J.R.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +43-1-40160-33023 Abstract: Ulceroglandular tularemia is caused by the transmission of Francisella tularensis by arthro- pods to a human host. We report a case of tick-borne tularemia in Austria which was followed by an abscess formation in a lymph node, making drainage necessary. F. tularensis subsp. holarctica was identified by PCR and multilocus sequence typing. Keywords: tularemia; Francisella tularensis; tick; multi locus sequence typing Depending on the transmission route of Francisella tularensis, tularemia can present Citation: Markowicz, M.; Schötta, as a local infection or a systemic disease [1]. Transmission of the pathogen takes place A.-M.; Penatzer, F.; Matscheko, C.; by contact with infected animals, by bites of arthropods or through contaminated water Stanek, G.; Stockinger, H.; Riedler, J. and soil. Hares and wild rabbits are the main reservoirs of the pathogen in Austria [2]. -

Rickettsia Felis, Bartonella Henselae, and B. Clarridgeiae, New Zealand

LETTERS Richard Reithinger,*† domestic and wild animals that also products obtained by PCR with Khoksar Aadil,† Samad Hami,† feeds readily on people. Recent stud- primers for the 17-kDa protein (4), and Jan Kolaczinski*† ies have implicated the cat flea as a citrate synthase (4), and PS 120 pro- *London School of Hygiene and Tropical vector of new and emerging infectious tein (5) genes. R. felis has been estab- Medicine, London, United Kingdom; and diseases (1). To determine the lished in tissue culture (XTC-2 and †HealthNet International, Peshawar, pathogens in C. felis in New Zealand, Vero cells) (6), and serologic testing Pakistan we collected 3 cat fleas from each of has been used to diagnose infections 11 dogs and 21 cats at the Massey (5). Reports indicate that patients References University Veterinary Teaching respond rapidly to doxycycline thera- 1. Ashford R, Kohestany K, Karimzad M. Hospital from May to June 2003. The py (5), and in vitro studies have Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Kabul: observa- fleas were stored in 95% alcohol until shown the organism is susceptible to tions on a prolonged epidemic. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 1992;86:361–71. they were identified by using morpho- rifampin, thiamphenicol, and fluoro- 2. Griffiths WDA. Old World cutaneous leish- logic criteria and washed in sterile quinolones. maniasis. In: Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R, phosphate-buffered saline. The DNA B. henselae is an agent of cat- editors. The leishmaniases in biology and from each flea was extracted individ- scratch disease, bacillary angiomato- medicine. London: Academic Press; 1987. p. 617–43. ually by using the QiaAmp Tissue Kit sis, bacillary peliosis, endocarditis, 3. -

Emerging Bartonellosis Christoph Dehio & Anna Sander

Emerging bartonellosis Christoph Dehio & Anna Sander Bartonellae are arthropod-borne pathogens of they cause a long-lasting infection within the red blood Ggrowing medical importance. Until the early cells (intraerythrocytic bacteraemia). Blood-sucking 1990s, only two species of this bacterial genus, arthropod vectors transmit the bacteria from this reservoir B. bacilliformis and B. quintana, were recognized as caus- to new hosts. Incidental infection of non-reservoir hosts ing disease in humans. In addition to re-emergence of the (e.g. humans by the zoonotic species) may cause disease, human-specific B. quintana, a number of zoonotic but does not result in intraerythrocytic infection. Bartonella species have now been recognized as causative agents for a broadening spectrum of diseases that can be Natural history and epidemiology transmitted to humans from their animal hosts. Most Humans are the only known reservoir for two Bartonella prominently, B. henselae is an important zoonotic species, B. bacilliformis and B. quintana. pathogen that is frequently passed from its feline B. quintana was a leading cause of infectious morbidity reservoir to humans. among soldiers during World War I, and recurred on the Bacteria of the genus Bartonella are Gram-negative, East European front in World War II. The disease, pleomorphic, fastidious bacilli that belong to the α-2 Trench fever, is rarely fatal and is characterized by an subclass of Proteobacteria. All Bartonella species appear intraerythrocytic bacteraemia with recurrent, cycling to have a specific mammalian species as a host, in which fever. It is transmitted among humans by the human body louse Pediculus humanus. Although almost forgotten Table 1. -

Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015

biology Article Laboratory Diagnostics of Rickettsia Infections in Denmark 2008–2015 Susanne Schjørring 1,2, Martin Tugwell Jepsen 1,3, Camilla Adler Sørensen 3,4, Palle Valentiner-Branth 5, Bjørn Kantsø 4, Randi Føns Petersen 1,4 , Ole Skovgaard 6,* and Karen A. Krogfelt 1,3,4,6,* 1 Department of Bacteria, Parasites and Fungi, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.T.J.); [email protected] (R.F.P.) 2 European Program for Public Health Microbiology Training (EUPHEM), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 27180 Solnar, Sweden 3 Scandtick Innovation, Project Group, InterReg, 551 11 Jönköping, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Virus and Microbiological Special Diagnostics, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 5 Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Prevention, Statens Serum Institut (SSI), 2300 Copenhagen, Denmark; [email protected] 6 Department of Science and Environment, Roskilde University, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark * Correspondence: [email protected] (O.S.); [email protected] (K.A.K.) Received: 19 May 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 19 June 2020 Abstract: Rickettsiosis is a vector-borne disease caused by bacterial species in the genus Rickettsia. Ticks in Scandinavia are reported to be infected with Rickettsia, yet only a few Scandinavian human cases are described, and rickettsiosis is poorly understood. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of rickettsiosis in Denmark based on laboratory findings. We found that in the Danish individuals who tested positive for Rickettsia by serology, the majority (86%; 484/561) of the infections belonged to the spotted fever group. -

Bartonella Henselae

Maggi et al. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:101 http://www.parasitesandvectors.com/content/6/1/101 RESEARCH Open Access Bartonella henselae bacteremia in a mother and son potentially associated with tick exposure Ricardo G Maggi1,3*, Marna Ericson2, Patricia E Mascarelli1, Julie M Bradley1 and Edward B Breitschwerdt1 Abstract Background: Bartonella henselae is a zoonotic, alpha Proteobacterium, historically associated with cat scratch disease (CSD), but more recently associated with persistent bacteremia, fever of unknown origin, arthritic and neurological disorders, and bacillary angiomatosis, and peliosis hepatis in immunocompromised patients. A family from the Netherlands contacted our laboratory requesting to be included in a research study (NCSU-IRB#1960), designed to characterize Bartonella spp. bacteremia in people with extensive arthropod or animal exposure. All four family members had been exposed to tick bites in Zeeland, southwestern Netherlands. The mother and son were exhibiting symptoms including fatigue, headaches, memory loss, disorientation, peripheral neuropathic pain, striae (son only), and loss of coordination, whereas the father and daughter were healthy. Methods: Each family member was tested for serological evidence of Bartonella exposure using B. vinsonii subsp. berkhoffii genotypes I-III, B. henselae and B. koehlerae indirect fluorescent antibody assays and for bacteremia using the BAPGM enrichment blood culture platform. Results: The mother was seroreactive to multiple Bartonella spp. antigens and bacteremia was confirmed by PCR amplification of B. henselae DNA from blood, and from a BAPGM blood agar plate subculture isolate. The son was not seroreactive to any Bartonella sp. antigen, but B. henselae DNA was amplified from several blood and serum samples, from BAPGM enrichment blood culture, and from a cutaneous striae biopsy. -

Bartonella: Feline Diseases and Emerging Zoonosis

BARTONELLA: FELINE DISEASES AND EMERGING ZOONOSIS WILLIAM D. HARDY, JR., V.M.D. Director National Veterinary Laboratory, Inc. P.O Box 239 Franklin Lakes, New Jersey 07417 201-891-2992 www.natvetlab.com or .net Gingivitis Proliferative Gingivitis Conjunctivitis/Blepharitis Uveitis & Conjunctivitis URI Oral Ulcers Stomatitis Lymphadenopathy TABLE OF CONTENTS Page SUMMARY……………………………………………………………………………………... i INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………… 1 MICROBIOLOGY……………………………………………………………………………... 1 METHODS OF DETECTION OF BARTONELLA INFECTION.………………………….. 1 Isolation from Blood…………………………………………………………………….. 2 Serologic Tests…………………………………………………………………………… 2 SEROLOGY……………………………………………………………………………………… 3 CATS: PREVALENCE OF BARTONELLA INFECTIONS…………………………………… 4 Geographic Risk factors for Infection……………………………………………………. 5 Risk Factors for Infection………………………………………………………………… 5 FELINE BARTONELLA DISEASES………………………………………………………….… 6 Bartonella Pathogenesis………………………………………………………………… 7 Therapy of Feline Bartonella Diseases…………………………………………………… 14 Clinical Therapy Results…………………………………………………………………. 15 DOGS: PREVALENCE OF BARTONELLA INFECTIONS…………………………………. 17 CANINE BARTONELLA DISEASES…………………………………………………………... 17 HUMAN BARTONELLA DISEASES…………………………………………………………… 18 Zoonotic Case Study……………………………………………………………………... 21 FELINE BLOOD DONORS……………………………………………………………………. 21 REFERENCES………………………………………………………………………………….. 22 This work was initiated while Dr. Hardy was: Professor of Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, Bronx, New York and Director, -

Transformation of Bartonella Bacilliformis by Electroporation

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1994 Transformation of Bartonella bacilliformis by electroporation Helen A. Grasseschi The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Grasseschi, Helen A., "Transformation of Bartonella bacilliformis by electroporation" (1994). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 7287. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/7287 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY TheMontana University of Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. * * P lease check **Yes ” o r **No ” and provide signature*"^ Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission /\ Author’s Signature Date: TG~ f^ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author’s explicit consent. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Transformation of Bartonella bacilliformis by Electroporation by Helen A. Grasseschi B. S., The University of Montana— Missoula, 1992 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Microbiology The University of Montana 1994 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners Daam, Graduate School £2, / 0 9 -/ Date ' Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Bartonella Is a Stealth Pathogen: It Hides Inside Red Blood Cells and the Cells of Blood-Vessel Walls

The Major Threat You’ve Never Heard Of BY SUE M. COPELAND This “stealth” bacteria is an emerging danger to your dog - and you. It also may be linked to the common canine cancer, hemangiosarcoma. Bartonella is a stealth pathogen: it hides inside red blood cells and the cells of blood-vessel walls. Once there, it eludes the body’s immune system, and often dodges detection by standard diagnostic blood tests. above photo ©North Carolina State University tell my veterinary students that, unless another infectious others, there now are 40 named species, of which 17 have been disease comes along that we don’t yet know about, such associated with an expanding spectrum of disease in dogs and hu- “I as covid-19 did in humans, Bartonella will cause them mans, as well as other mammals. more problems in their careers than anything else.” The bacteria lives inside blood cells and is transmitted by car- That quote is from Edward Breitschwerdt, DVM, DACVIM, riers, known as vectors, which include fleas, lice, and sand flies; Melanie S. Steele Professor of Medicine and Infectious Disease Bartonella DNA has also been found in ticks. These vectors are at North Carolina State University (NCSU) College of Veterinary found on and around such animals as dogs, cats, coyotes, rac- Medicine. He’s been studying the bacteria for 30 years. coons, cows, foxes, horses, rodents, and bats. Bartonellosis is a “Wait, what?” you ask. “What the heck is Bartonella?” zoonotic disease, meaning it can be transmitted from your pets It’s an emerging threat that research is showing can be associ- or other mammals, to humans.