Rabindranath Tagore ( 1861 - 194 1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48P

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48p. Rs.30 It Is the famous rhymes collection of Bengali Literature. 2. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 60p. Rs.30 It in the most popular Bengala Rhymes ener written. 3. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Dey's 1990; 48p. Rs.10 It is the most famous rhyme collection of Bengali Literature. 4. Aachin Paakhi Dutta, Asit : Nikhil Bharat Shishu Sahitya 2002; 48p. Rs.30 Eight-stories, all bordering on humour by a popular writer. 5. Aadhikar ke kake dei Mukhophaya, Sutapa Kolkata: A 'N' E Publishers 1999; 28p. Rs.16 8185136637 This book intend to inform readers on their Rights and how to get it. 6. Aagun - Pakhir Rahasya Gangopadhyay, Sunil Kolkata: Ananda Publishers 1996; 119p. Rs.30 8172153198 It is one of the most famous detective story and compilation of other fun stories. 7. Aajgubi Galpo Bardhan, Adrish (ed.) : Orient Longman 1989; 117p. Rs.12 861319699 A volume on interesting and detective stories of Adrish Bardhan. 8. Aamar banabas Chakraborty, Amrendra : Swarnakhar Prakashani 1993; 24p. Rs.12 It is nice poetry for childrens written by Amarendra Chakraborty. 9. Aamar boi Mitra, Premendra : Orient Longman 1988; 40p. Rs.6 861318080 Amar Boi is a famous Primer-cum-beginners book written by Premendra Mitra. 10. Aat Rahasya Phukan, Bandita New Delhi: Fantastic ; 168p. Rs.27 This is a collection of eight humour A Mystery Stories. 12. Aatbhuture Mitra, Khagendranath Kolkata: Ashok Prakashan 1996; 140p. Rs.25 A collection of defective stories pull of wonder & surprise. 13. Abak Jalpan lakshmaner shaktishel jhalapala Ray, Kumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 58p. -

Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist a Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd

2018 Heritage Vol.-V Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist A Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd. Associate Professor, Dept. of Political Science, Bethune College, Kolkata-6 Abstract: Rabindranath Tagore, although basically a poet, had a multifaceted personality. Among his various activities his sincerity as a social thinker and activist attract our attention. But this area is till now comparatively unexplored. Many scholars in this area have tried to study Tagore as a social thinker. But so far the findings are scattered and on the whole there is no comprehensive analysis in the strict sense of the term. Hence it is necessary to collect the different findings and to integrate and arrange them within a theoretical framework. This article is an attempt to make a review of literature of the existing books and to prepare a short but sharp bibliography to introduce the area. Key words: Rabindranath Tagore, society, social, political, history, education, Santiniketan, Visva-Bharati Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941) was a prolific writer, a successful music composer, a painter, an actor, a drama director and what not. Besides these talents, he was also a social activist and contributed a lot to Indian social and political thought, although this area has not been very much explored till now. Tagore was emphatic upon society building. So he tried to develop all the component elements which were essential for developing the Indian society. He studied the history of India to follow the trend of its evolution. Next he prepared his programme of action – rural reconstruction and spread of education. -

Letter Correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: a Study

Annals of Library and Information Studies Vol. 59, June 2012, pp. 122-127 Letter correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: A Study Partha Pratim Raya and B.K. Senb aLibrarian, Instt. of Education, Visva-Bharati, West Bengal, India, E-mail: [email protected] b80, Shivalik Apartments, Alakananda, New Delhi-110 019, India, E-mail:[email protected] Received 07 May 2012, revised 12 June 2012 Published letters written by Rabindranath Tagore counts to four thousand ninety eight. Besides family members and Santiniketan associates, Tagore wrote to different personalities like litterateurs, poets, artists, editors, thinkers, scientists, politicians, statesmen and government officials. These letters form a substantial part of intellectual output of ‘Tagoreana’ (all the intellectual output of Rabindranath). The present paper attempts to study the growth pattern of letters written by Rabindranath and to find out whether it follows Bradford’s Law. It is observed from the study that Rabindranath wrote letters throughout his literary career to three hundred fifteen persons covering all aspects such as literary, social, educational, philosophical as well as personal matters and it does not strictly satisfy Bradford’s bibliometric law. Keywords: Rabindranath Tagore, letter correspondences, bibliometrics, Bradfords Law Introduction a family man and also as a universal man with his Rabindranath Tagore is essentially known to the many faceted vision and activities. Tagore’s letters world as a poet. But he was a great short-story writer, written to his niece Indira Devi Chaudhurani dramatist and novelist, a powerful author of essays published in Chhinapatravali1 written during 1885- and lectures, philosopher, composer and singer, 1895 are not just letters but finer prose from where innovator in education and rural development, actor, the true picture of poet Rabindranath as well as director, painter and cultural ambassador. -

2021 Banerjee Ankita 145189

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The Santiniketan ashram as Rabindranath Tagore’s politics Banerjee, Ankita Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 THE SANTINIKETAN ashram As Rabindranath Tagore’s PoliTics Ankita Banerjee King’s College London 2020 This thesis is submitted to King’s College London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy List of Illustrations Table 1: No of Essays written per year between 1892 and 1936. -

IP Tagore Issue

Vol 24 No. 2/2010 ISSN 0970 5074 IndiaVOL 24 NO. 2/2010 Perspectives Six zoomorphic forms in a line, exhibited in Paris, 1930 Editor Navdeep Suri Guest Editor Udaya Narayana Singh Director, Rabindra Bhavana, Visva-Bharati Assistant Editor Neelu Rohra India Perspectives is published in Arabic, Bahasa Indonesia, Bengali, English, French, German, Hindi, Italian, Pashto, Persian, Portuguese, Russian, Sinhala, Spanish, Tamil and Urdu. Views expressed in the articles are those of the contributors and not necessarily of India Perspectives. All original articles, other than reprints published in India Perspectives, may be freely reproduced with acknowledgement. Editorial contributions and letters should be addressed to the Editor, India Perspectives, 140 ‘A’ Wing, Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi-110001. Telephones: +91-11-23389471, 23388873, Fax: +91-11-23385549 E-mail: [email protected], Website: http://www.meaindia.nic.in For obtaining a copy of India Perspectives, please contact the Indian Diplomatic Mission in your country. This edition is published for the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi by Navdeep Suri, Joint Secretary, Public Diplomacy Division. Designed and printed by Ajanta Offset & Packagings Ltd., Delhi-110052. (1861-1941) Editorial In this Special Issue we pay tribute to one of India’s greatest sons As a philosopher, Tagore sought to balance his passion for – Rabindranath Tagore. As the world gets ready to celebrate India’s freedom struggle with his belief in universal humanism the 150th year of Tagore, India Perspectives takes the lead in and his apprehensions about the excesses of nationalism. He putting together a collection of essays that will give our readers could relinquish his knighthood to protest against the barbarism a unique insight into the myriad facets of this truly remarkable of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar in 1919. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara ISSN: 2469-0783 [email protected] Fundación MenteClara Argentina Basu, Ratan Lal Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, vol. 3, no. 2, 2018, April-September 2019, pp. 7-30 Fundación MenteClara Argentina DOI: https://doi.org/10.32351/rca.v3.2.43 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=563560859001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension Ratan Lal Basu Artículos atravesados por (o cuestionando) la idea del sujeto -y su género- como una construcción psicobiológica de la cultura. Articles driven by (or questioning) the idea of the subject -and their gender- as a cultural psychobiological construction Vol. 3 (2), 2018 ISSN 2469-0783 https://datahub.io/dataset/2018-3-2-e43 TAGORE-OCAMPO RELATION, A NEW DIMENSION RELACIÓN TAGORE-OCAMPO, UNA NUEVA DIMENSIÓN Ratan Lal Basu [email protected] Presidency College, Calcutta & University of Calcutta, India. Cómo citar este artículo / Citation: Basu R. L. (2018). « Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension». Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, 3(2) abril-septiembre 2018, 7-30. DOI: 10.32351/rca.v3.2.43 Copyright: © 2018 RCAFMC. Este artículo de acceso abierto es distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-cn) Spain 3.0. Recibido: 23/05/2018. -

Redescubriendo a Rabindranath Tagore –

i i ii ii REDESCUBRIENDO A TAGORE con el motivo del 150 aniversario del natalicio del vate indio Edición a cargo de Shyama Prasad Ganguly Indranil Chakravarty Esta es una publicación de Indo-Latin American Cultural Initiative, Mumbai en colaboración con Sahitya Akademi, Nueva Delhi y la Embajada de España en la India iii iii © de la edición: Indo-Latin American Cultural Initiative, 2011 © de las traducciones al castellano: ILACI © de los textos originales: los autores Primera edición, Septiembre de 2011 amaranta es la imprenta editorial de ILACI, dedicada a publicar la literatura india en castellano y la literatura española y latinoamericana en los idiomas de la india que incluye el inglés [email protected] Publicado por Indranil Chakravarty en nombre de ILACI, Green Meadows: 1C/501, Lokhandwala, Kandivali East, Mumbai: 400101, India ISBN: 978-81-921843-1-9 Diseño y maquetación: AnM Design Studio, Mumbai Imágenes: Según indicadas Quedan prohibidos, dentro de los límites establecidos en la ley y bajo los apercibimientos legalmente previstos, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento, ya sea electrónico o mecánico, el tratamiento informático, el alquiler o cualquier otra forma de cesión de la obra sin la autorización previa y por escrito de los titulares de los derechos. Impreso en Manjul Graphics, Mumbai iv iv a mi padre, Madhu Sudan Ganguly por ser ejemplo de sencillez e inspiración a mi hijo, Shagnik Chakravarty por darme fortaleza v v Índice Palabras Preliminares ix Indranil Chakravarty Introducción -

S Public and Hantipur a Private Co and Its Neig Ollections Ghbourhoo Od

EAP643: Shantipur and its neighbourhood: Text and images of early modern Bengal in public and private collections Mr Abhijit Bhattacharya, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta 2013 award - Pilot project £9,300 for 8 months EAP643 has supplied an inventory of the collections surveyed which can be seen in the document below. Summary Page 2 Santipur Brahmo Samaj Collection Page 10 Krittibas Memorial Library Collection Page 75 Santipur Sahitya Parishad Collection Page 95 L M Sen Collection Page 327 Municipality Collection Page 355 Santipur Bangiya Purana Parisha Page 355 Further Information You can contact the EAP team at [email protected] 1 Summary Count "0" (not available in other holdings) OCLC BL SBS 288 351 KMLM 89 108 SSP 1398 1570 L. M. Sen Municipality Listing will be done only after digitisation. SBPP Listing will be done only after digitisation. Count "1" (available in other holdings) OCLC BL SBS 112 49 KMLM 29 10 SSP 237 65 L. M. Sen Municipality Listing will be done only after digitisation. SBPP Listing will be done only after digitisation. Sl. Subject in SSP No. Of No. Books 1 About Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy and his institute. 1 2 About ancient bengali poets 1 3 About ancient bengali writers 1 4 About Buddha 1 2 5 About Indian Legend Women 1 6 About Library 1 7 About Textile 1 8 About Weavers 1 9 Aesthetics 1 10 Archeological 1 11 Arithmatic 1 12 Articles of Vidyasagar 1 13 Baby Care 1 14 Bengali Literature 1 15 Bengali text Book 1 16 Biography & Poems Collection 1 17 Biography of poets 1 18 Cattle Farming -

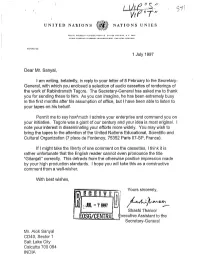

M R // Vvt/ Ffi*R~F~'R 7 F UNITED Natiions ||W NATIONS UNIES

M r // VVt/ ffi*R~f~'r 7 f UNITED NATiIONS ||W NATIONS UNIES s. N.V. loot? REFERENCE: 1 July 1997 Dear Mr. Sanyal, I am writing, belatedly, in reply to your letter of 8 February to the Secretary- General, with which you enclosed a selection of audio cassettes of renderings of the work of Rabindranath Tagore. The Secretary-General has asked me to thank you for sending these to him. As you can imagine, he has been extremely busy in the first months after his assumption of office, but I have been able to listen to your tapes on his behalf. Permit me to say how'much I admire your enterprise and commend you on your initiative. Tagore was a giant of our century and your idea is most original. I note your interest in disseminating your efforts more widely. You may wish to bring the tapes to the attention of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (7 place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07-SP, France). If I might take the liberty of one comment on the cassettes, I think it is rather unfortunate that the English reader cannot even pronounce the title "Gitanjali" correctly. This detracts from the otherwise positive impression made by your high production standards. I hope you will take this as a constructive comment from a well-wisher. With best wishes, Yours sincerely, Shashi Tharoor xecutive Assistant to the Secretary-General Mr. Alok Sanyal CD40, Sector 1 Salt Lake City Calcutta 700 064 INDIA M1BHH Alok Sanyal ph. D. Mailing Address : Department of Physics, Jadavpur University CD 40, SECTOR I SALT LAKE CITY W] CALCUTTA-700064 INDIA Telephone +91 33 337 5037/337 59U8 +91 33 U40 8656 UNITED N-ew Y*vK MY 10017 Indian poets especially the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore lead the list of Asian writers who'have been most translated into the languages of the world.