Family, School and Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48P

1. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Patra Bharati 2003; 48p. Rs.30 It Is the famous rhymes collection of Bengali Literature. 2. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 60p. Rs.30 It in the most popular Bengala Rhymes ener written. 3. Aabol Taabol Roy, Sukumar Kolkata: Dey's 1990; 48p. Rs.10 It is the most famous rhyme collection of Bengali Literature. 4. Aachin Paakhi Dutta, Asit : Nikhil Bharat Shishu Sahitya 2002; 48p. Rs.30 Eight-stories, all bordering on humour by a popular writer. 5. Aadhikar ke kake dei Mukhophaya, Sutapa Kolkata: A 'N' E Publishers 1999; 28p. Rs.16 8185136637 This book intend to inform readers on their Rights and how to get it. 6. Aagun - Pakhir Rahasya Gangopadhyay, Sunil Kolkata: Ananda Publishers 1996; 119p. Rs.30 8172153198 It is one of the most famous detective story and compilation of other fun stories. 7. Aajgubi Galpo Bardhan, Adrish (ed.) : Orient Longman 1989; 117p. Rs.12 861319699 A volume on interesting and detective stories of Adrish Bardhan. 8. Aamar banabas Chakraborty, Amrendra : Swarnakhar Prakashani 1993; 24p. Rs.12 It is nice poetry for childrens written by Amarendra Chakraborty. 9. Aamar boi Mitra, Premendra : Orient Longman 1988; 40p. Rs.6 861318080 Amar Boi is a famous Primer-cum-beginners book written by Premendra Mitra. 10. Aat Rahasya Phukan, Bandita New Delhi: Fantastic ; 168p. Rs.27 This is a collection of eight humour A Mystery Stories. 12. Aatbhuture Mitra, Khagendranath Kolkata: Ashok Prakashan 1996; 140p. Rs.25 A collection of defective stories pull of wonder & surprise. 13. Abak Jalpan lakshmaner shaktishel jhalapala Ray, Kumar Kolkata: National Book Agency 2003; 58p. -

Where the Mind Is Without Fear” Lecture by Bindu Gulati Lecturer English Bindu [email protected] 9872463799 About the Poet

“Where the Mind is Without Fear” Lecture by Bindu Gulati Lecturer English Bindu [email protected] 9872463799 About the Poet Rabindranath Tagore is to Indians what Shakespeare is to the English. He founded Shanti Niketan which promoted naturalistic philosophy of teaching. Kabuliwala, Geetanjali, Gora are few of his famous works. He won Nobel Prize for Literature for his work “Geetanjali”. Where the Mind is Without Fear Introduction The poet draws a picture of free India. He dreamt of a country with no boundaries. This poem is his idealistic dream about India . It is self explanatory. Tagore prays for the welfare of the country. Poem Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high; Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls; Where words come out from the depth of truth; Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection ; Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit ; Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever- widening thought and action…….. Into the heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake. EXPLANATION WITH REFERENCE TO THE CONTEXT Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high; Where knowledge is free; Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls; Where words come out from the depth of truth; Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection . Word meanings 1. Fragments- pieces 2. Head is held high- self respect 3. -

Premendra Mitra - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Premendra Mitra - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Premendra Mitra(1904 - 3 May 1988) Premendra Mitra was a renowned Bengali poet, novelist, short story writer and film director. He was also an author of Bangla science fiction and thrillers. <b>Life</b> He was born in Varanasi, India, though his ancestors lived at Rajpur, South 24 Parganas, West Bengal. His father was an employee of the Indian Railways and because of that; he had the opportunity of travelling to many places in India. He spent his childhood in Uttar Pradesh and his later life in Kolkata & Dhaka. He was a student of South Suburban School (Main) and later at the Scottish Church College in Kolkata. During his initial years, he (unsuccessfully) aspired to be a physician and studied the natural sciences. Later he started out as a school teacher. He even tried to make a career for himself as a businessman, but he was unsuccessful in that venture as well. At a time, he was working in the marketing division of a medicine producing company. After trying out the other occupations, in which he met marginal or moderate success, he rediscovered his talents for creativity in writing and eventually became a Bengali author and poet. Married to Beena Mitra, he was, by profession, a Bengali professor at City College in north Kolkata. He spent almost his entire life in a house at Kalighat, Kolkata. <b>As an Author & Editor</b> In November 1923, Mitra came from Dhaka, Bangladesh and stayed in a mess at Gobinda Ghoshal Lane, Kolkata. -

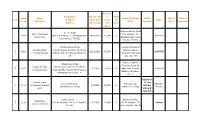

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

Tagore: (泰戈尔) a Case Study of His Visit to China in 1924

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 19, Issue 3, Ver. V (Mar. 2014), PP 28-35 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Tagore: (泰戈尔) A Case study of his visit to China in 1924 Sourabh Chatterjee (Mody University of Science and Technology, India) Abstract: In 1923, Beijing Lecture Association, Jiangxueshe (讲学社) invited Rabindranath Tagore to deliver a series of lecturers. Established in September 1920, Jiangxueshe was one of the many globally acclaimed institutions that mushroomed in China in the wake of the May Fourth Movement. The main objective of this institution was to invite foreign scholars and celebrities to arrange lectures by them for Chinese intellectuals. They thought it will help the Chinese intellects to be prospers in many aspects, which will enrich their country. Every year, they used to invite the most respected global figures, research scholars, scientists, and noble laureates to deliver their valuable speeches and sermons. Before Rabindranath, the Association invited some dignified global figures like John Dewey (1859-1952), Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) and Hans Driesch (1862- 1941). Most of them were not able to move them in a great way. Anyway, as the Chinese association felt that they were not receiving expected result after inviting so many global scholars, they finally decided to invite Rabindranath to their country. It is worthy to be mentioned here, some fervent critics and scholars like Das, Sun and Hay have averred that Tagore’s visit to China created two fold reactions among the people of China. Tagore’s visit to China received both friendly and hostile reactions from them. -

Annual Report, 2012-13 1 Head of the Department

Annual Report, 2012-13 1 CHAPTER II DEPARTMENT OF BENGALI Head of the Department : SIBABRATA CHATTOPADHYAY Teaching Staff : (as on 31.05.2013) Professor : Dr. Krishnarup Chakraborty, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Asish Kr. Dey, M.A., Ph.D Dr Amitava Das, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Sibabrata Chattopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Arun Kumar Ghosh, M.A., Ph.D Dr Uday Chand Das, M.A., Ph.D Associate Professor : Dr Ramen Kr Sar, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Arindam Chottopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr Anindita Bandyopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Alok Kumar Chakraborty, M.A., Ph.D Assistant Professor : Ms Srabani Basu, M.A. Field of Studies : A) Mediaval Bengali Lit. B) Fiction & Short Stories, C) Tagore Lit. D) Drama Student Enrolment: Course(s) Men Women Total Gen SC ST Total Gen SC ST Total Gen SC ST Total MA/MSc/MCom 1st Sem 43 25 09 77 88 17 03 108 131 42 12 185 2nd Sem 43 25 09 77 88 17 03 108 131 42 12 185 3rd Sem 43 28 08 79 88 16 02 106 131 44 10 185 4th Sem 43 28 08 79 88 16 02 106 131 44 10 185 M.Phil 01 01 01 01 02 02 01 03 Research Activities :(work in progress) Sl.No. Name of the Scholar(s) Topic of Research Supervisor(s) 1. Anjali Halder Binoy Majumdarer Kabitar Nirmanshaily Prof Amitava Das 2. Debajyoti Debnath Unishsho-sottor paraborti bangla akhayaner dhara : prekshit ecocriticism Prof Uday Chand Das 3. Prabir Kumar Baidya Bangla sahitye patrikar kromobikas (1851-1900) Dr.Anindita Bandyopadhyay 4. -

Hawkers' Movement in Kolkata, 1975-2007

NOTES hawkers’ cause. More than 32 street-based Hawkers’ Movement hawker unions, with an affiliation to the mainstream political parties other than the in Kolkata, 1975-2007 ruling Communist Party of India (Marxist), better known as CPI(M), constitute the body of the HSC. The CPI(M)’s labour wing, Centre Ritajyoti Bandyopadhyay of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), has a hawk- er branch called “Calcutta Street Hawkers’ In Kolkata, pavement hawking is n recent years, the issue of hawkers Union” that remains outside the HSC. The an everyday phenomenon and (street vendors) occupying public space present paper seeks to document the hawk- hawkers represent one of the Iof the pavements, which should “right- ers’ movement in Kolkata and also the evo- fully” belong to pedestrians alone, has lution of the mechanics of management of largest, more organised and more invited much controversy. The practice the pavement hawking on a political ter- militant sectors in the informal of hawking attracts critical scholarship rain in the city in the last three decades, economy. This note documents because it stands at the intersection of with special reference to the activities of the hawkers’ movement in the city several big questions concerning urban the HSC. The paper is based on the author’s governance, government co-option and archival and field research on this subject. and reflects on the everyday forms of resistance (Cross 1998), property nature of governance. and law (Chatterjee 2004), rights and the Operation Hawker, 1975 very notion of public space (Bandyopadhyay In 1975, the representatives of Calcutta 2007), mass political activism in the context M unicipal Corporation (henceforth corpora- of electoral democracy (Chatterjee 2004), tion), Calcutta Metropolitan Development survival strategies of the urban poor in the Authority (CMDA), and the public works context of neoliberal reforms (Bayat 2000), d epartment (PWD) jointly took a “decision” and so forth. -

Rabindranath's Nationalist Thought

5DELQGUDQDWK¶V1Dtionalist T hought: A Retrospect* Narasingha P. Sil** Abstract : 7DJRUH¶VDQWL-absolutist and anti-statist stand is predicated primarily on his vision of global peace and concord²a world of different peoples and cultures united by amity and humanity. While this grand vision of a brave new world is laudable, it is, nevertheless, constructed on misunderstanding and misreading of history and of the role of the nation state in the West since its rise sometime during the late medieval and early modern times. Tagore views state as an artificial mechanism, indeed a machine thDWWKULYHVRQFRHUFLRQFRQIOLFWDQGWHUURUE\VXEYHUWLQJSHRSOH¶VIUHHGRPDQG culture. This paper seeks to argue that the state also played historically a significant role in enhancing and enriching culture and civilization. His view of an ideal human society is sublime, but by the same token, somewhat ahistorical and anti-modern., K eywords: Anarchism, Babu, Bengal Renaissance, deshaprem [patriotism], bishwajiban [universal life], Gessellschaft, Gemeinschaft, jatiyatabad [nationalism], rastra [state], romantic, samaj [society], swadeshi [indigenous] * $QHDUOLHUVKRUWHUYHUVLRQRIWKLVSDSHUWLWOHG³1DWLRQDOLVP¶V8JO\)DFH7DJRUH¶V7DNH5HYLVLWHG´ZDVSUHVHQWHGWR the Social Science Seminar, Western Oregon University on January 27, 2010 and I thank its convener Professor Eliot Dickinson of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration for inviting me. All citations in Bengali appear in my translation unless stated otherwise. BE stands for Bengali Era that follows the -

Rabindranath Tagore's Model of Rural Reconstruction: a Review

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT.– DEC. 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Rabindranath Tagore’s Model of Rural Reconstruction: A review Dr. Madhumita Chattopadhyay Assistant Professor in English, B.Ed. Department, Gobardanga Hindu College (affiliated to West Bengal State University), P.O. Khantura, Dist- 24 Parganas North, West Bengal, PIN – 743273. Received: July 07, 2018 Accepted: August 17, 2018 ABSTRACT Rabindranath Tagore’s unique venture on rural reconstruction at Silaidaha-Patisar and at Sriniketan was a pioneering work carried out by him with the motto of the wholesome development of the community life of village people through education, training, healthcare, sanitation, modern and scientific agricultural production, revival of traditional arts and crafts and organizing fairs and festivities in daily life. He believed that through self-help, self-initiation and self-reliance, village people will be able to help each other in their cooperative living and become able to prepare the ground work for building the nation as an independent country in the true sense. His model of rural reconstruction is the torch-bearer of so many projects in independent India. His principles associated with this programme are still relevant in the present day world, but is not out of criticism. The need is to make critical analysis and throw new lights on this esteemed model so that new programmes can be undertaken based on this to achieve ‘life in its completeness’ among rural population in India. Keywords: Rural reconstruction, cooperative effort, community development. Introduction Rathindranath Tagore once said, his father was “a poet who was an indefatigable man of action” and “his greatest poem is the life he has lived”. -

Public Health Research Series

UNIVERSITY Public Health Research Series 2012 Vol.1, Issue 1 School of Public Health I Preface “A scientist writes not because he wants to say something, but because he has something to say” – F. Scott Fitzgerald The above quote more or less summarizes the essence of this publication. The School of Public Health, SRM University takes great pride and honor in bringing out the first of its Public Health Research Series, a compilation of research papers by the bright and intelligent students of the school. The Series has come out to provide a platfrom for sharing of research work by students and faculty in the field of publuc health. The studies reported in this Series are small pilot projects with scope for scaling up in larger scale to address important public health issues in India. They come from diverse settings spanning the length and breadth of the country, neighboring countries like Nepal and Bhutan, diverse linguistic, cultural and socio economic backgrounds. Some of the projects have generated important hypothesis for further testing, some have done qualitative exploration of interesting concepts and yet others have tried to quantify certain constructs in public health. This book is organized into a set of 25 full reports and 5 briefs. The full reports give an elaborate description of the study objectives, methods and findings with interpretations and discussions of the authors. The briefs are unstructured concept abstracts. The studies were done by the students of the school of public health as their term project under the guidance of the faculty mentors to whom they were assigned at the time of enrolment into the course. -

Pather Panchali

February 19, 2002 (V:5) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian and Bruce Jackson SATYAJIT RAY (2 May 1921,Calcutta, West Bengal, India—23 April 1992, Calcutta) is one of the half-dozen universally P ATHER P ANCHALI acknowledged masters of world cinema. Perhaps the best starting place for information on him is the excellent UC Santa Cruz (1955, 115 min., 122 within web site, the “Satjiyat Ray Film and Study Collection” http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/. It's got lists of books by and about Ray, a Bengal) filmography, and much more, including an excellent biographical essay by Dilip Bausu ( Also Known As: The Lament of the http://arts.ucsc.edu/rayFASC/detail.html) from which the following notes are drawn: Path\The Saga of the Road\Song of the Road. Language: Bengali Ray was born in 1921 to a distinguished family of artists, litterateurs, musicians, scientists and physicians. His grand-father Upendrakishore was an innovator, a writer of children's story books, popular to this day, an illustrator and a musician. His Directed by Satyajit Ray father, Sukumar, trained as a printing technologist in England, was also Bengal's most beloved nonsense-rhyme writer, Written by Bibhutibhushan illustrator and cartoonist. He died young when Satyajit was two and a half years old. Bandyopadhyay (also novel) and ...As a youngster, Ray developed two very significant interests. The first was music, especially Western Classical music. Satyajit Ray He listened, hummed and whistled. He then learned to read music, began to collect albums, and started to attend concerts Original music by Ravi Shankar whenever he could.