Coastal Demographics in Victoria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gippsland Roadmap

9 Dec 2019 The Energy Innovation Foreword Co-operative1, which has 10 years of experience On behalf of the Victorian Government, I am pleased to present the Victorian Regional Renewable Energy Roadmaps. delivering community-based As we transition to cleaner energy with new opportunities for jobs and greater security of supply, we are looking to empower communities, accelerate renewable energy and build a more sustainable and prosperous energy efficiency and state. renewable energy initiatives in Victoria is leading the way to meet the challenges of climate change by enshrining our Victorian Renewable Energy Targets (VRET) into law: 25 per the Southern Gippsland region, cent by 2020, rising to 40 per cent by 2025 and 50 per cent by 2030. Achieving the 2030 target is expected to boost the Victorian economy by $5.8 billion - driving metro, regional and rural industry and supply chain developed this document in development. It will create around 4,000 full time jobs a year and cut power costs. partnership with Community It will also give the renewable energy sector the confidence it needs to invest in renewable projects and help Victorians take control of their energy needs. Power Agency (community Communities across Barwon South West, Gippsland, Grampians and Loddon Mallee have been involved in discussions to help define how Victoria engagement and community- transitions to a renewable energy economy. These Roadmaps articulate our regional communities’ vision for a renewable energy future, identify opportunities to attract investment and better owned renewable energy understand their community’s engagement and capacity to transition to specialists)2, Mondo renewable energy. -

Epidemics and Pandemics in Victoria: Historical Perspectives

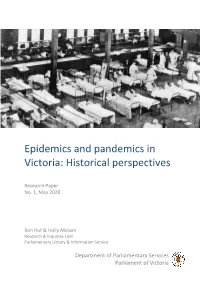

Epidemics and pandemics in Victoria: Historical perspectives Research Paper No. 1, May 2020 Ben Huf & Holly Mclean Research & Inquiries Unit Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Annie Wright, Caley Otter, Debra Reeves, Michael Mamouney, Terry Aquino and Sandra Beks for their help in the preparation of this paper. Cover image: Hospital Beds in Great Hall During Influenza Pandemic, Melbourne Exhibition Building, Carlton, Victoria, circa 1919, unknown photographer; Source: Museums Victoria. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) Research Paper: No. 1, May 2020 © 2020 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the -

Transporting Melbourne's Recovery

Transporting Melbourne’s Recovery Immediate policy actions to get Melbourne moving January 2021 Executive Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted how Victorians make decisions for when, where and how they travel. Lockdown periods significantly reduced travel around metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria due to travel restrictions and work-from-home directives. As Victoria enters the recovery phase towards a COVID Normal, our research suggests that these travel patterns will shift again – bringing about new transport challenges. Prior to the pandemic, the transport network was struggling to meet demand with congested roads and crowded public transport services. The recovery phase adds additional complexity to managing the network, as the Victorian Government will need to balance competing objectives such as transmission risks, congestion and stimulating greater economic activity. Governments across the world are working rapidly to understand how to cater for the shifting transport demands of their cities – specifically, a disruption to entire transport systems that were not designed with such health and biosecurity challenges in mind. Infrastructure Victoria’s research is intended to assist the Victorian Government in making short-term policy decisions to balance the safety and performance of the transport system with economic recovery. The research is also designed to inform decision-making by industry and businesses as their workforces return to a COVID Normal. It focuses on how the transport network may handle returning demand and provides options to overcome the crowding and congestion effects, while also balancing the health risks posed by potential local transmission of the virus. Balancing these impacts is critical to fostering confidence in public transport travel, thereby underpinning and sustaining Melbourne’s economic recovery. -

Gippsland-Regional-Growth-Plan

GIPPSLAND REGIONAL GROWTH PLAN BACKGROUND REPORT Acknowledgement of Country The Gippsland Local Government Network and the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure acknowledge Aboriginal Traditional Owners within the region, their rich culture and spiritual connection to Country. We also recognise and acknowledge the contribution and interest of Aboriginal people and organisations in land use planning, land management and natural resource management. Authorised and published by the Victorian Government, 1 Treasury Place, Melbourne Printed by Finsbury Green, Melbourne If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, please telephone 1300 366 356. This document is also available in Word format at www.dtpli.vic.gov.au/regionalgrowthplans Unless indicated otherwise, this work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of the licence, visit creativecommons.org/licences/by/3.0/au It is a condition of this Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licence that you must give credit to the original author who is the State of Victoria. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you, but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. March 2014 Table of contents ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................................... -

Extending Out-Of-Home Care in the State of Victoria, Australia: the Policy Context and Outcomes

Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care Volume 20.1 Extending out-of-home care in the state of Victoria, Australia: The policy context and outcomes Philip Mendes Abstract In November 2020, the State (Labour Party) Government of Victoria in Australia announced that it would extend out-of-home care (OOHC) on a universal basis until 21 years of age starting 1 January 2021. This is an outstanding policy innovation introduced in response to the Home Stretch campaign, led by Anglicare Victoria, to urge all Australian jurisdictions to offer extended care programmes until at least 21 years. It also reflects the impact of more than two decades of advocacy by service providers, researchers, and care experienced young people (Mendes, 2019). Keywords Care experience, out-of-home care, aftercare, care leaving, extended care, staying put, Australia Corresponding author: Philip Mendes, Associate Professor, Monash University Department of Social Work, [email protected] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License Scottish Journal of Residential Child Care ISSN 1478 – 1840 CELCIS.ORG Extending out-of-home care in the state of Victoria, Australia: The policy context and outcomes Background Australia has a federal out-of-home care (OOHC) system by which transition from care policy and practice differs according to the specific legislation and programmes in the eight states and territories. In June 2019, there were nearly 45,000 children in OOHC nationally of whom the majority (92 per cent in total) were either in relative/kinship care or foster care. Only about six per cent lived in residential care homes supervised by rostered staff. -

Volcanoes in SW Victoria & SE South Australia

Volcanoes in SW Victoria & SE South Australia June 2005. The volcanic plains of western Victoria form a belt 100 km wide which extends 350 km west from Melbourne nearly to the South Australian border. In addition, several volcanoes occur near Mt. Gambier. The gently undulating plains are formed of lava flows up to 60 m thick, and are studded with volcanic hills. About 400 volcanoes are known within the region, which has been erupting intermittently for the last five million years. The youngest volcano appears to be Mt. Schank, in South Australia, which erupted about 5,000 years ago. The Aborigines would have watched this and some of the other eruptions, and they have stories of burning mountains. Further eruptions could happen, but are not likely in our lifetimes. Volcanoes erupt when molten material (called magma, in this state at about 1200°C) is forced up from great depths. On reaching the surface this may flow across the ground as lava, or be blasted into the air by gas pressure to build up cones of fragmentary material (including scoria and ash). Most of the local volcanoes erupted for only a few weeks or months, and never again – the next eruption was at a new site. In the Western District there are mainly three types of volcano, though combinations of these also occur: About half of the volcanoes are small steep-sided scoria cones built from frothy lava fragments thrown up by lava fountains. A group of about 40 maar craters near the coast were formed from shallow steam-driven explosions that produced broad craters with low rims. -

The Border Groundwaters Agreement

THE BORDER IMPORTANCE OF GROUNDWATER AND These zones and any aquifer in the zone can be divided into two POTENTIAL PROBLEMS or more sub-zones. GROUNDWATERS The Agreement provides that the available groundwater shall In most areas close to the South Australian-Victorian State be shared equitably between the states. It applies to all existing AGREEMENT border, groundwater is the only reliable source of water. It is used and future bores within the Designated Area except domestic for irrigation and for industrial, stock and domestic supplies. and stock bores which are exempt from the Agreement. Bore Many towns close to the border also rely on groundwater for construction licences and permits or extraction licences may their public water supply. not be granted or renewed within the Designated Area by Information Sheet 1 of 4 Large groundwater withdrawals on one side of the border could either state unless they conform to management prescriptions affect users on the other side, possibly interfering with their set by the Agreement. long-term supplies. In addition, groundwater salinity increase can occur due to excessive use of groundwater. To prevent this, the Governments of South Australia and Victoria entered into an agreement for the management of the groundwater resource. 140° 142° THE BORDER GROUNDWATERS AGREEMENT 34° Managing the Ri ver Renmark Groundwater The Groundwater (Border Agreement) Act 1985 came into effect Mildura in January 1986 to cooperatively manage the groundwater SA Resources across the VIC resources along the state border of South Australia and Victoria. Loxton Murray Zone Zone South Australian - As understanding of the resource improved and the demand 11A 11B Victorian Border for water increased, there was a need to manage the resource in MURRAY a more targeted way to take account of aquifer characteristics ADELAIDE The Border Groundwaters and specific circumstances. -

Grampians and Barwon South West Region Passenger Services Cost & Feasibility Study

GRAMPIANS AND BARWON SOUTH WEST REGION PASSENGER SERVICES COST & FEASIBILITY STUDY FINAL REPORT March 2017 John Hearsch Consulting Pty Ltd 2 Steering Committee Peter Brown, CEO, Horsham Rural City Council Andrew Evans, CEO, Ararat Rural City Council Michael McCarthy, Director Shire Futures, Southern Grampians Shire Council Maree McNeilly, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources Angela Daraxaglou, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources Chris Banger, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources Jozef Vass, Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources Study Co-ordinator: Susan Surridge, Horsham Rural City Council Study Team John Hearsch, Study Director Dr Bill Russell Peter Don Participating Councils Ararat Rural City Council Northern Grampians Shire Glenelg Shire Southern Grampian Shire Hindmarsh Shire West Wimmera Shire Horsham Rural City Council Yarriambiack Shire Grampians and Barwon South West Passenger Services Cost & Feasibility Study– John Hearsch Consulting Pty Ltd, Page 2 3 GRAMPIANS AND BARWON SOUTH WEST REGION PASSENGER SERVICES COST & FEASIBILITY STUDY Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 6 Findings ............................................................................................................................ 8 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... -

Alpine National Park

Alpine Grazing Taskforce Report ReportREPORT of theON THE investigation INVESTIGATION into INTO the futureTHE FUTURE of cattle OF CATTLE grazing GRAZING in the IN THE AlpineALPINE National NATIONAL Park PARK ALPINE GRAZING TASKFORCE (replace with new cover) Alpine Grazing Taskforce Al MARCH 2005 Published by the Victorian Government Department of Sustainability and Environment May 2005 Also published on www.dse.vic.gov.au/alpinegrazing © The State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2005 for the Alpine Grazing Taskforce This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne Printed by Impact Digital, 69–79 Fallon Street, Brunswick ISBN 1 74152 124 6 This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. For further information contact the DSE Customer Service Centre on 136 186. [Signed letter from Taskforce to Minister.] Alpine Grazing Taskforce Report 2 Alpine Grazing Taskforce Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Taskforce findings 5 Part One – Introduction 9 1 The Taskforce 11 The Alpine National Park grazing issue 11 The Alpine Grazing Taskforce 11 Consultation 12 -

Australia's System of Government

61 Australia’s system of government Australia is a federation, a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. This means that Australia: Has a Queen, who resides in the United Kingdom and is represented in Australia by a Governor-General. Is governed by a ministry headed by the Prime Minister. Has a two-chamber Commonwealth Parliament to make laws. A government, led by the Prime Minister, which must have a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Has eight State and Territory Parliaments. This model of government is often referred to as the Westminster System, because it derives from the United Kingdom parliament at Westminster. A Federation of States Australia is a federation of six states, each of which was until 1901 a separate British colony. The states – New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania - each have their own governments, which in most respects are very similar to those of the federal government. Each state has a Governor, with a Premier as head of government. Each state also has a two-chambered Parliament, except Queensland which has had only one chamber since 1921. There are also two self-governing territories: the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. The federal government has no power to override the decisions of state governments except in accordance with the federal Constitution, but it can and does exercise that power over territories. A Constitutional Monarchy Australia is an independent nation, but it shares a monarchy with the United Kingdom and many other countries, including Canada and New Zealand. The Queen is the head of the Commonwealth of Australia, but with her powers delegated to the Governor-General by the Constitution. -

Executive Summary Grampians and Barwon South West Region

Grampians and Barwon South West Region Passenger Services Study – March 2017 Executive Summary This Study of the passenger service needs of the Grampians and Barwon South West regions was commissioned by eight local government councils in western Victoria, and covers the area from Ararat to the South Australian border and from Yarriambiack in the north to Glenelg Shire in the south. Councils asked the Study Team to investigate the extent to which existing passenger services – both train and coach – supported the social and economic requirements of this large and productive region, and whether the services currently provided and the infrastructure used could be improved. Councils wanted passenger services and infrastructure that would improve social and economic access and connectivity, reduce isolation, and enable the present and future residents of the region to easily connect with regional centres and Melbourne to meet social, economic, medical, educational and business needs through safe, efficient, frequent and reliable public transport. Central to this issue was whether train services could be reinstated to Horsham, Hamilton and other centres. The Report is based on extensive investigation, and many meetings with councillors, council officers, business leaders, educational and health services and residents in the region. The Study Team also reviewed social and economic statistics for the region in detail. It investigated rail and coach operational questions in fine detail. The work undertaken by the Study Team identified significant unmet needs for better public transport in the region. The Study found that residents, businesses, government agencies and local governments in the region were not being provided with fast public transport access to Ballarat and Melbourne. -

Infrastructure Strategy

Victoria’s Draft 30-Year Infrastructure Strategy Develop regional Victoria Infrastructure Victoria’s draft 30-year infrastructure strategy considers the infrastructure needs for all of Victoria. The opportunities and challenges for regional Infrastructure strengthens wellbeing in and rural communities are different to those in regional Victoria by connecting people to Melbourne but we found that many infrastructure essential resources and tackling disadvantage needs are shared across the regions. experienced by Victoria’s most vulnerable communities. Each region has unique attributes that can grow economies, create jobs and transform Recommendations specific to the regions industries. Infrastructure investments that build have been developed to address unique on a region’s existing competitive strengths infrastructure needs for: or advantages are most likely to effectively \ Barwon deliver future economic growth. Infrastructure \ Central Highlands must also support communities during natural disasters and prepare them for long-term \ Gippsland climate change. \ Goulburn \ Great South Coast The regions of Victoria \ Loddon Campaspe \ Mallee \ Ovens Murray \ Wimmera Southern Mallee. Enhance market access and Foster regional Victorians’ health, productivity safety and inclusion Regional Victoria is home to key local and export Transport and telecommunications infrastructure industries. Infrastructure plays an important role in can support improved access to services in regional connecting businesses with their markets, boosting areas. Yet