Extending Out-Of-Home Care in the State of Victoria, Australia: the Policy Context and Outcomes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epidemics and Pandemics in Victoria: Historical Perspectives

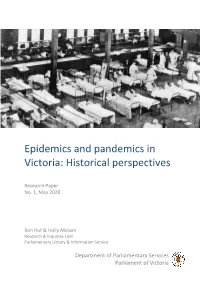

Epidemics and pandemics in Victoria: Historical perspectives Research Paper No. 1, May 2020 Ben Huf & Holly Mclean Research & Inquiries Unit Parliamentary Library & Information Service Department of Parliamentary Services Parliament of Victoria Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank Annie Wright, Caley Otter, Debra Reeves, Michael Mamouney, Terry Aquino and Sandra Beks for their help in the preparation of this paper. Cover image: Hospital Beds in Great Hall During Influenza Pandemic, Melbourne Exhibition Building, Carlton, Victoria, circa 1919, unknown photographer; Source: Museums Victoria. ISSN 2204-4752 (Print) 2204-4760 (Online) Research Paper: No. 1, May 2020 © 2020 Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Parliament of Victoria Research Papers produced by the Parliamentary Library & Information Service, Department of Parliamentary Services, Parliament of Victoria are released under a Creative Commons 3.0 Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs licence. By using this Creative Commons licence, you are free to share - to copy, distribute and transmit the work under the following conditions: . Attribution - You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non-Commercial - You may not use this work for commercial purposes without our permission. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without our permission. The Creative Commons licence only applies to publications produced by the -

Transporting Melbourne's Recovery

Transporting Melbourne’s Recovery Immediate policy actions to get Melbourne moving January 2021 Executive Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted how Victorians make decisions for when, where and how they travel. Lockdown periods significantly reduced travel around metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria due to travel restrictions and work-from-home directives. As Victoria enters the recovery phase towards a COVID Normal, our research suggests that these travel patterns will shift again – bringing about new transport challenges. Prior to the pandemic, the transport network was struggling to meet demand with congested roads and crowded public transport services. The recovery phase adds additional complexity to managing the network, as the Victorian Government will need to balance competing objectives such as transmission risks, congestion and stimulating greater economic activity. Governments across the world are working rapidly to understand how to cater for the shifting transport demands of their cities – specifically, a disruption to entire transport systems that were not designed with such health and biosecurity challenges in mind. Infrastructure Victoria’s research is intended to assist the Victorian Government in making short-term policy decisions to balance the safety and performance of the transport system with economic recovery. The research is also designed to inform decision-making by industry and businesses as their workforces return to a COVID Normal. It focuses on how the transport network may handle returning demand and provides options to overcome the crowding and congestion effects, while also balancing the health risks posed by potential local transmission of the virus. Balancing these impacts is critical to fostering confidence in public transport travel, thereby underpinning and sustaining Melbourne’s economic recovery. -

Annual Report 2019-2020 Chairperson’S Report Youth Advocacy in a Year Like No Other Yacvic Works Across the Entire State of Victoria

Annual Report 2019-2020 chairperson’s Report Youth advocacy in a year like no other YACVic works across the entire state of Victoria. YACVic’s head office is based on the lands of the Kulin Nation in Naarm (Melbourne). We It goes without saying that this also have offices based on the lands of the Gunditjmara Nation in Warrnambool, and on the lands of the Wemba Wemba, Wadi Wadi and has been a year like no other, Weki Weki Nations in Swan Hill. and the board and I could not YACVic gives our deepest respect to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Elders past, present and emerging for their wisdom, strength, support be prouder of how YACVic has and leadership. supported young people and the We acknowledge all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Victoria, and stand in solidarity to pay respect to the ongoing culture sector during this strange and and continued history of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nations. challenging time. In a year where our members have faced bushfires and COVID-19, YACVic has played a central role in keeping YACVic is the leading advocate for young people aged 12–25 in Victoria. young people’s needs and experiences on the public As a peak body, we work closely with young Victorians and the sector that and political agenda, and supported the youth sector supports them to deliver effective advocacy, events, training, resources and to address them in these unprecedented times. We support—so that young people can live their best lives. We’re driven by our have also helped interpret all the policy changes and Chairperson Kerrie Loveless, CEO Katherine Ellis, and The Hon valued members and their vision for a positive future for young Victorians. -

Annual Report

We promote and build a vibrant, strong volunteering community that is inclusive, respected and sustainable Our year at a glance 518 Volunteer managers received individualised support with their role Research submissions & Guides 801 107 Individuals Additional received assistance Members to find a volunteer role 20 Mentors 25 MENTORING In-House 6 PROGRAM Training Webinars 20 Sessions Mentees 174 170 Attendees Victoria ALIVE forum 13 attendees Public Workshops 241 Attendees Total Funding: $1,054,486 Total Members: 412 “I thank the Board of Volunteering Victoria for their leadership and vision” Anthony Carbines, Parliamentary Secretary for Carers and Volunteers Contents 3 Message from Chair & CEO 4 Inside Volunteering Victoria 5 Our Members 6 Policy & Advocacy 8 Sector Development & Events 12 State Conference 2019 13 Volunteering in Victoria 14 Sharing our Message Victoria 15 Victoria ALIVE 17 Sponsors & Supporters 18 Our Members Directory 21 Summary of Accounts Message from Chair & CEO Volunteering Victoria took a significant step forward in securing its future this year. Board and Staff members demonstrated their resiliency and ability to reimagine value to members and funders by energising, enhancing and connecting people and programs in line with our strategic and operational priorities. Our message this year uses the same theme as our State conference to share with you how our Board and staff worked to promote and build a vibrant, strong volunteering community that is inclusive, respected and sustainable. Energising The Board’s release of the 2019-2021 Strategic Plan was received very well. Members have reported their connection with the ambitious agenda to transform volunteer management and volunteering into the next decade. -

Volcanoes in SW Victoria & SE South Australia

Volcanoes in SW Victoria & SE South Australia June 2005. The volcanic plains of western Victoria form a belt 100 km wide which extends 350 km west from Melbourne nearly to the South Australian border. In addition, several volcanoes occur near Mt. Gambier. The gently undulating plains are formed of lava flows up to 60 m thick, and are studded with volcanic hills. About 400 volcanoes are known within the region, which has been erupting intermittently for the last five million years. The youngest volcano appears to be Mt. Schank, in South Australia, which erupted about 5,000 years ago. The Aborigines would have watched this and some of the other eruptions, and they have stories of burning mountains. Further eruptions could happen, but are not likely in our lifetimes. Volcanoes erupt when molten material (called magma, in this state at about 1200°C) is forced up from great depths. On reaching the surface this may flow across the ground as lava, or be blasted into the air by gas pressure to build up cones of fragmentary material (including scoria and ash). Most of the local volcanoes erupted for only a few weeks or months, and never again – the next eruption was at a new site. In the Western District there are mainly three types of volcano, though combinations of these also occur: About half of the volcanoes are small steep-sided scoria cones built from frothy lava fragments thrown up by lava fountains. A group of about 40 maar craters near the coast were formed from shallow steam-driven explosions that produced broad craters with low rims. -

The Border Groundwaters Agreement

THE BORDER IMPORTANCE OF GROUNDWATER AND These zones and any aquifer in the zone can be divided into two POTENTIAL PROBLEMS or more sub-zones. GROUNDWATERS The Agreement provides that the available groundwater shall In most areas close to the South Australian-Victorian State be shared equitably between the states. It applies to all existing AGREEMENT border, groundwater is the only reliable source of water. It is used and future bores within the Designated Area except domestic for irrigation and for industrial, stock and domestic supplies. and stock bores which are exempt from the Agreement. Bore Many towns close to the border also rely on groundwater for construction licences and permits or extraction licences may their public water supply. not be granted or renewed within the Designated Area by Information Sheet 1 of 4 Large groundwater withdrawals on one side of the border could either state unless they conform to management prescriptions affect users on the other side, possibly interfering with their set by the Agreement. long-term supplies. In addition, groundwater salinity increase can occur due to excessive use of groundwater. To prevent this, the Governments of South Australia and Victoria entered into an agreement for the management of the groundwater resource. 140° 142° THE BORDER GROUNDWATERS AGREEMENT 34° Managing the Ri ver Renmark Groundwater The Groundwater (Border Agreement) Act 1985 came into effect Mildura in January 1986 to cooperatively manage the groundwater SA Resources across the VIC resources along the state border of South Australia and Victoria. Loxton Murray Zone Zone South Australian - As understanding of the resource improved and the demand 11A 11B Victorian Border for water increased, there was a need to manage the resource in MURRAY a more targeted way to take account of aquifer characteristics ADELAIDE The Border Groundwaters and specific circumstances. -

Australia's System of Government

61 Australia’s system of government Australia is a federation, a constitutional monarchy and a parliamentary democracy. This means that Australia: Has a Queen, who resides in the United Kingdom and is represented in Australia by a Governor-General. Is governed by a ministry headed by the Prime Minister. Has a two-chamber Commonwealth Parliament to make laws. A government, led by the Prime Minister, which must have a majority of seats in the House of Representatives. Has eight State and Territory Parliaments. This model of government is often referred to as the Westminster System, because it derives from the United Kingdom parliament at Westminster. A Federation of States Australia is a federation of six states, each of which was until 1901 a separate British colony. The states – New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and Tasmania - each have their own governments, which in most respects are very similar to those of the federal government. Each state has a Governor, with a Premier as head of government. Each state also has a two-chambered Parliament, except Queensland which has had only one chamber since 1921. There are also two self-governing territories: the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. The federal government has no power to override the decisions of state governments except in accordance with the federal Constitution, but it can and does exercise that power over territories. A Constitutional Monarchy Australia is an independent nation, but it shares a monarchy with the United Kingdom and many other countries, including Canada and New Zealand. The Queen is the head of the Commonwealth of Australia, but with her powers delegated to the Governor-General by the Constitution. -

Chart 1 Victoria: Top 30 Countries of Birth, 2016 Census

Chart 3Victoria: 30 Local Top Government Areas, Number of Overseas-Born, Census 2016 Census 2016 and Chart 2Victoria: 30 Overseas Top Countries of Birth Increase by in Numbers between 2011 Chart 1Victoria: 30 Countries Top of Birth, Census 2016 Persons, overseas-born Persons, increase Persons 100,000 120,000 140,000 160,000 180,000 200,000 140,000 100,000 120,000 10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000 60,000 70,000 20,000 40,000 60,000 80,000 80,000 20,000 40,000 60,000 80,000 Casey (C) PR China 0 0 0 England Brimbank (C) Wyndham (C) 114,422 66,756 171,443 India India Philippines PR China 93,001 58,015 169,802 Gter Dandenong (C) New Zealand New Zealand Monash (C) 90,248 13,288 160,652 Vietnam Vietnam Melbourne (C) 89,590 13,019 93,253 87,766 Pakistan 12,490 80,787 Italy Hume (C) Sri Lanka Sri Lanka Whittlesea (C) 75,797 11,938 70,527 Philippines Malaysia Whitehorse (C) 70,535 11,839 55,830 70,138 10,259 Malaysia 51,290 Moreland (C) AfghanistanIran 62,353 9,181 Greece 50,049 Glen Eira (C) South Africa Boroondara (C) 55,227 8,171 47,240 Iraq 51,747 Myanmar 5,842 Germany 27,184 Darebin (C) 51,744 Thailand 5,366 Scotland 26,308 Local Government Area Kingston (C) Hong Kong 48,848 5,212 26,073 South KoreaNepal Country ofbirth Country ofbirth ManninghamKnox (C) 47,252 5,081 Pakistan 21,642 Netherlands 46,510 Taiwan 4,605 21,125 Hong Kong Gter GeelongMelton (C) 46,376 4,214 19,813 USA Maribyrnong (C) 40,613 3,438 19,695 South AfricaUSA AfghanistanIraq Stonnington (C) 37,981 2,850 18,637 Moonee Valley (C) Bangladesh 32,988 2,737 18,116 Malta FYR of -

Stopping Hate in Its Tracks

Ruth Barson and Monique Hurley Human Rights Law Centre Email: [email protected] Shen Narayanasamy GetUp! Email: [email protected] Dr Dvir Abramovich Anti Defamation Commission Email: [email protected] Mairead Lesman Victorian Trades Hall Council Email: [email protected] Abiola Ajetomobi Asylum Seeker Resource Centre Email: [email protected] The authors of this submission acknowledge the people of the Kulin Nation, the traditional owners of the unceded land on which our offices sit, and the ongoing work of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, communities and organisations to unravel the injustices imposed on First Nations people since colonisation and demand justice for First Nations peoples. 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 2. THE RISE OF HATE 6 3. EFFECTIVENESS OF CURRENT LAWS 8 4. THE NEED TO PROTECT BROADER ATTRIBUTES 10 Attributes protected in other jurisdictions 10 Intersectionality 11 5. BEST PRACTICE LAWS TO PREVENT HATE 12 Change the name of the Act 12 Enact better civil tests for vilification 13 Enact better criminal tests for serious vilification 16 Specific provision prohibiting the public display of vilification materials 17 Specific provision on causing a person to have a reasonable fear 19 Striking the right balance 20 6. IMPROVED ENFORCEMENT PROVISIONS 21 7. ADDRESSING ONLINE VILIFICATION 21 8. THE NEED TO PREVENT HATE-BASED CONDUCT 22 1. This Anti-Vilification Protections Inquiry (Inquiry) presents a unique opportunity for the Victorian Government to enact best practice anti-hate laws that promote a diverse, safe and harmonious community, and that stop hate in its tracks. 2. The organisations making this submission first came together in response to the Hammered Music Festival being advertised online in late 2019 by white supremacist hate groups Blood & Honour Australia and the Southern Cross Hammerskins. -

Victoria/Tasmania

The Essential First Step. Victoria/Tasmania New Staff Restructure Events The Dial Before You Dig Vic/Tas team has recently had a Together with the team at Energy Safe Victoria, the Dial staff re-structure. Before You Dig Vic/Tas team held stands at both the Ben Howell, State Manager and Simon Surrao, Marketing Bairnsdale and Mildura Field Days. The field days gives Coordinator remain in their current roles. Dial Before You Dig the opportunity to interact with the rural/farming community. Both events were a great Joe Fiala has taken up the position as the new Manager success. Joe Fiala was fortunate to share a moment with Strategic Relations and Angela Gilmore has joined the our Deputy Prime Minister, Barnaby Joyce. team as the Engagement and Education Coordinator. Angela’s most recent roles have been in Community Engagement for Local Government in regional Victoria. Angela has relocated with her family from Surf Coast to Preston in Victoria and is so far enjoying the busyness of city life. She is looking forward to engaging with Members and delivering awareness sessions across Vic/Tas over the coming months. Carla is the newest member of the Dial Before Your Dig Vic/Tas team, and has come on board as Assistant to the Vic/Tas State Manager and Administration Coordinator. “I’m so happy to have joined the Vic/Tas team and am very much looking forward to assisting with all aspects Joe Fiala and Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce of office support. I enjoy keeping people organized, and Other events have included the sponsorship of the Master am dedicated to making the lives of busy people easier. -

Federal & State Mp Phone Numbers

FEDERAL & STATE MP PHONE NUMBERS Contact your federal and state members of parliament and ask them if they are committed to 2 years of preschool education for every child. Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Federal electorate MP’s name Political party Phone Aston Alan Tudge Liberal (03) 9887 3890 Hotham Clare O’Neil Labor (03) 9545 6211 Ballarat Catherine King Labor (03) 5338 8123 Indi Catherine McGowan Independent (03) 5721 7077 Batman Ged Kearney Labor (03) 9416 8690 Isaacs Mark Dreyfus Labor (03) 9580 4651 Bendigo Lisa Chesters Labor (03) 5443 9055 Jagajaga Jennifer Macklin Labor (03) 9459 1411 Bruce Julian Hill Labor (03) 9547 1444 Kooyong Joshua Frydenberg Liberal (03) 9882 3677 Calwell Maria Vamvakinou Labor (03) 9367 5216 La Trobe Jason Wood Liberal (03) 9768 9164 Casey Anthony Smith Liberal (03) 9727 0799 Lalor Joanne Ryan Labor (03) 9742 5800 Chisholm Julia Banks Liberal (03) 9808 3188 Mallee Andrew Broad National 1300 131 620 Corangamite Sarah Henderson Liberal (03) 5243 1444 Maribyrnong William Shorten Labor (03) 9326 1300 Corio Richard Marles Labor (03) 5221 3033 McEwen Robert Mitchell Labor (03) 9333 0440 Deakin Michael Sukkar Liberal (03) 9874 1711 McMillan Russell Broadbent Liberal (03) 5623 2064 Dunkley Christopher Crewther Liberal (03) 9781 2333 Melbourne Adam Bandt Greens (03) 9417 0759 Flinders Gregory Hunt Liberal (03) 5979 3188 Melbourne Ports Michael Danby Labor (03) 9534 8126 Gellibrand Timothy Watts Labor (03) 9687 7661 Menzies Kevin Andrews Liberal (03) 9848 9900 Gippsland Darren Chester National -

Coastal Demographics in Victoria

Coastal demographics in Victoria Background research paper prepared for the Background research paper prepared for the VictorianVictorian Marine Coastal and Coastal Council Council 2018 Author Dr Fiona McKenzie, Principal Researcher, Land Use and Population Research, DELWP. Photo credit Photo: Metung 2008 taken by Anne Barlow DELWP © The State of Victoria Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 2020 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence. You are free to re-use the work under that licence, on the condition that you credit the State of Victoria as author. The licence does not apply to any images, photographs or branding, including the Victorian Coat of Arms, the Victorian Government logo and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) logo. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN 978-1-76077-450-9 (pdf/online/MS word) Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an alternative format, please telephone the DELWP Customer Service Centre on 136186, email [email protected], or via the National Relay Service on 133 677 www.relayservice.com.au. This document is also available on the internet at www.delwp.vic.gov.au.