Mental Health and Healing with the Carrier First Nation: Views of Seven Traditional Healers and Knowledge Holders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language List 2019

First Nations Languages in British Columbia – Revised June 2019 Family1 Language Name2 Other Names3 Dialects4 #5 Communities Where Spoken6 Anishnaabemowin Saulteau 7 1 Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN 1. Anishinaabemowin Ojibway ~ Ojibwe Saulteau Plains Ojibway Blueberry River First Nations Fort Nelson First Nation 2. Nēhiyawēwin ᓀᐦᐃᔭᐍᐏᐣ Saulteau First Nations ALGONQUIAN Cree Nēhiyawēwin (Plains Cree) 1 West Moberly First Nations Plains Cree Many urban areas, especially Vancouver Cheslatta Carrier Nation Nak’albun-Dzinghubun/ Lheidli-T’enneh First Nation Stuart-Trembleur Lake Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation Lhtako Dene Nation (Tl’azt’en, Yekooche, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Nak’azdli) Nak’azdli Whut’en ATHABASKAN- ᑕᗸᒡ NaZko First Nation Saik’uz First Nation Carrier 12 EYAK-TLINGIT or 3. Dakelh Fraser-Nechakoh Stellat’en First Nation 8 Taculli ~ Takulie NA-DENE (Cheslatta, Sdelakoh, Nadleh, Takla Lake First Nation Saik’uZ, Lheidli) Tl’azt’en Nation Ts’il KaZ Koh First Nation Ulkatcho First Nation Blackwater (Lhk’acho, Yekooche First Nation Lhoosk’uz, Ndazko, Lhtakoh) Urban areas, especially Prince George and Quesnel 1 Please see the appendix for definitions of family, language and dialect. 2 The “Language Names” are those used on First Peoples' Language Map of British Columbia (http://fp-maps.ca) and were compiled in consultation with First Nations communities. 3 The “Other Names” are names by which the language is known, today or in the past. Some of these names may no longer be in use and may not be considered acceptable by communities but it is useful to include them in order to assist with the location of language resources which may have used these alternate names. -

A GUIDE to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013)

A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) A GUIDE TO Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia (December 2013) INTRODUCTORY NOTE A Guide to Aboriginal Organizations and Services in British Columbia is a provincial listing of First Nation, Métis and Aboriginal organizations, communities and community services. The Guide is dependent upon voluntary inclusion and is not a comprehensive listing of all Aboriginal organizations in B.C., nor is it able to offer links to all the services that an organization may offer or that may be of interest to Aboriginal people. Publication of the Guide is coordinated by the Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch of the Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation (MARR), to support streamlined access to information about Aboriginal programs and services and to support relationship-building with Aboriginal people and their communities. Information in the Guide is based upon data available at the time of publication. The Guide data is also in an Excel format and can be found by searching the DataBC catalogue at: http://www.data.gov.bc.ca. NOTE: While every reasonable effort is made to ensure the accuracy and validity of the information, we have been experiencing some technical challenges while updating the current database. Please contact us if you notice an error in your organization’s listing. We would like to thank you in advance for your patience and understanding as we work towards resolving these challenges. If there have been any changes to your organization’s contact information please send the details to: Intergovernmental and Community Relations Branch Ministry of Aboriginal Relations and Reconciliation PO Box 9100 Stn Prov. -

Understanding Our Lives Middle Years Development Instrumentfor 2019–2020 Survey of Grade 7 Students

ONLY USE UNDERSTANDING OUR LIVES MIDDLE YEARS DEVELOPMENT INSTRUMENTFOR 2019–2020 SURVEY OF GRADE 7 STUDENTS BRITISH COLUMBIA You can preview the survey online at INSTRUCTIONALSAMPLE SURVEY www.mdi.ubc.ca. NOT © Copyright of UBC and contributors. Copying, distributing, modifying or translating this work is expressly forbidden by the copyright holders. Contact Human Early Learning Partnership at [email protected] to obtain copyright permissions. Version: Sep 13, 2019 H18-00507 IMPORTANT REMINDERS! 1. Prior to starting the survey, please read the Student Assent on the next page aloud to your students! Students must be given the opportunity to decline and not complete the survey. Students can withdraw anytime by clicking the button at the bottom of every page. 2. Each student has their own login ID and password assigned to them. Students need to know that their answers are confidential, so that they will feel more comfortable answering the questions honestly. It is critical that they know this is not a test, and that there are no right or wrong answers. 3. The “Tell us About Yourself” section at the beginning of the survey can be challenging for some students. Please read this section aloud to make sure everybody understands. You know your students best and if you are concerned about their reading level, we suggest you read all of the survey questions aloud to your students. 4. The MDI takes about one to two classroom periods to complete.ONLY The “Activities” section is a natural place to break. USE Thank you! What’s new on the MDI? 1. We have updated questions 5-7 on First Nations, Métis and Inuit identity, and First Nations languages learned and spoken at home. -

Lheidli T'enneh Perspectives on Resource Development

THE PARADOX OF DEVELOPMENT: LHEIDLI T'ENNEH PERSPECTIVES ON RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT by Geoffrey E.D. Hughes B.A., Northern Studies, University of Northern British Columbia, 2002 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN FIRST NATIONS STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA November 2011 © Geoffrey Hughes, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1 Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87547-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-87547-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

BC – Community Accessibility Status

Indigenous Services Canada – BC – Community Accessibility Status Report Jan 28 – Feb 4 Disclaimer: The information below is based on reporting to ISC and information posted publicly and is updated as information becomes available. BC Region Total Band/Nation Status Band State of Emergency Access Restrictions Offices Local Operations Inaccessible Emergency Centre First Nations Security 69 202 141 (+3) Checkpoints (-1) 91 (+1) 80 (-1) 113 Band Office Accessibility Tribal Council Office Accessibility Inaccessible – 91 (+1) Inaccessible - 15 Appointment Only – 71 (+3) Appointment Only - 2 Accessible – 27 (-4) Accessible - 2 Unknown – 12 Unknown - 6 Definitions Communities that are implementing some sort of system to control access which may Access Restrictions include security checkpoints, and varies between communities. Does not necessarily signify that access to a community is completely closed. State of Local A declaration made by authorized representatives of a First Nation to indicate that an emergency that exceeds community capacity exists. This may or may not be in the form Emergency of a Band Council Resolution or other notification, and usually identifies the nature of the (SOLE) emergency as well as the duration of the declaration. Emergency Operations An temporary organization/structure that comes together during an emergency to Centre coordinate response and recovery actions and resources. (EOC) Inaccessible The office is completely closed to the public - ie. no regular walk-ins nor appointments. The office is available to the public on a case-by-case basis and only via appointment. No Appointment Only walk-ins. Fully Accessible The office is fully accessible to the public. Business as usual. Percentage of Band Offices Inaccessable 6% Inaccessable 14% 45% Appt. -

REGIONAL DISTRICT of BULKLEY-NECHAKO SUPPLEMENTARY AGENDA Thursday, March 19, 2020

1 REGIONAL DISTRICT OF BULKLEY-NECHAKO SUPPLEMENTARY AGENDA Thursday, March 19, 2020 PAGE NO. DELEGATION ACTION 2-21 Regional District of Bulkley Nechako Receive Food and Agriculture Plan 2020 PowerPoint Presentation (see Board Agenda) PLANNING (All Directors) ACTION 22 Report of the Public Hearing Receive Bylaw No. 1800 (Board Agenda Pages 67-127) 23 Rezoning Application A-07-19 Receive (Hansen North Valley) – Report of the Public Hearing for Bylaw Nos. 1901 & 1902 (Board Agenda Pages 128-140) ADMINISTRATION REPORTS Recommendation 24 John Illes, Chief Financial Officer - Budget Update – Vanderhoof Pool 25-146 Debbie Evans, Agriculture Coordinator Receive - RDBN Food and Agriculture Plan ADMINISTRATION CORRESPONDENCE 147-148 Climate Leaders Forum Receive - May 12, 2020, Prince George, B.C. NEW BUSINESS ADJOURNMENT 2 Regional District of Bulkley Nechako Food and Agriculture Plan 2020 RDBN Board of Directors, March 19, 2020 With research, engagement, planning, and production support provided by: 3 Goals for updating the 2012 Agriculture Plan 1. Update baseline data and information on the food and agriculture sector in the RDBN. 2. Engage stakeholders in creating a shared vision for food and agriculture in the RDBN and updating the 2012 (food) and agriculture plan. 3. Update policies and actions to reflect new data and information, consumer and producer perspectives, as well as provincial legislative changes. 4. Establish a sound factual basis for informing recommendations and decision making. 5. Create a detailed 5-7 year action and implementation -

Provincial-Heritage-Conversation-Act

February 12, 2016 Permit File: 2014-0087 Rob Paterson Ecofor Consulting Ltd., Fort St John 9940 - 104 Avenue Fort St. John, BC V1J 1Y6 Email: [email protected] Re: Amendment to Inspection Permit 2014-0087 - Granted Dear Rob Paterson: Further to your request of January 4, 2016, the terms of the enclosed permit have been revised to extend the expiry date to March 31, 2017. Please note that as this amendment is administrative in nature, it has not been sent out for comment, but issued directly. Please keep a copy of the amended permit for your records; the original will be retained in the Archaeology Branch permit file. The results of your inspections are to be presented in a permit report, submitted in both double-sided hard copy and PDF formats, by March 31, 2017. Individuals and organizations with knowledge of location, distribution and significance of archaeological resources in the study area should be contacted where appropriate, and documented in the permit report. Please ensure that site inventory forms are submitted separately, and that detailed site access information is not included in the report text. If site forms are included in the report, they will be removed by Branch staff. Please note that Branch acceptance of permit reports only acknowledges the fulfillment of permit terms and conditions. Such acceptance does not bring with it an obligation by the Branch to accept report recommendations as they relate to impact assessments or impact management requirements. Should you have any questions regarding this permit, please contact your Project Officer, Margaret Rogers, who can be reached by calling (250) 953-3311, or emailing [email protected]. -

(Sernbc) First Nations Collaboration: Final Report

Society for Ecosystem Restoration in North Central BC (SERNbc) First Nations Collaboration: Final Report Prepared By: Ecofor Consulting Ltd. 1575 2nd Avenue Prince George, BC V2L 3B8 Jennifer Herkes March 18, 2016 © Ecofor Consulting Ltd. SERNbc First Nations Collaboration Final Report SERNbc First Nations Collaboration: Final Report Prepared By: Ecofor Consulting Ltd. 1575 2nd Avenue Prince George, BC V2L 3B8 Report Prepared for: SERNbc, Society for Ecosystem Restoration in North Central British Columbia 1560 Highway 16 Vanderhoof, BC V0J 3A0 CREDITS Author Chandra Young-Boyle, MA Editor Jennifer Herkes, MA Mapping Margie Massier, BSc ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Ecofor Consulting Ltd. prepared this report for the Society for Ecosystem Restoration in Northeastern BC (SERNbc). Jennifer Herkes, Chandra Young-Boyle, and Kevin Wilson would like to thank John DeGagne for his support throughout the duration of the project. We would also like to thank Lake Babine Nation, Tsay Keh Dene, Saulteau First Nation, Lhoosk’uz Dené Nation, Nazko First Nation, and Nak’azdli First Nation (and Nus De Environmental), for their time and participation in this project. ECOFOR natural and cultural resource consultants ii SERNbc First Nations Collaboration Final Report MANAGEMENT SUMMARY Ecofor Consulting Ltd. contacted and communicated with First Nations of the Omineca Natural Resource Region at the request of John DeGagne of SERNbc. Ecofor’s role was to continue work that was initiated in 2015, acting to facilitate communication between SERNbc and First Nations within the Omineca. The intent is to develop collaborative projects and aim towards ongoing, cooperative working relationships between SERNbc and the First Nations of the Omineca. The work was conducted by telephone, email, and in-person meetings between December 2015 and March 2016. -

Lhoosk'uz Dené Nation and Ulkatcho First Nation Part C Blackwater Gold Mine Project

Lhoosk’uz Dené Nation and Ulkatcho First Nation Part C Blackwater Gold Mine Project (Blackwater) May 10, 2019 Written and compiled by Keefer Ecological Services Ltd. Ulkatcho First Nation and Lhoosk’uz Dené Nation Part C – Blackwater Gold Mine Project May 10, 2019 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................ 5 1. Collaborative Assessment of the Project ...................................................................................... 7 1.1. Who we are: Lhoosk’uz Dené Nation & Ulkatcho First Nation................................................... 7 2. Collaborative Assessment Process Overview .............................................................................. 10 2.1. Memorandum of Understanding (MOU): How we got here ........................................................ 10 2.2. What does the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) mean? ................................................. 11 3. Ulkatcho and Lhoosk’uz Dené Assessment Methodology .......................................................... 11 3.1. Ulkatcho and Lhoosk’uz Dené perspectives on health values .................................................. 12 3.2. How the methodology was applied .......................................................................................... 15 4. Lhoosk’uz -

Spirit of Unity 2017 Success Booklet

Success Booklet Spirit of Unity 2016/17 Achievement Awards June 6, 2017 Gala Spirit of Unity 2016/17 Achievement Awards Gala Work… Life… Balance Each year PGNAETA hosts a Spirit of Unity Forum. For the past five years the event has been enhanced by the Spirit of Unity Achievement Awards Gala to acknowledge and celebrate the contributions and successes of organizations, companies and individuals who have performed admirably in fields of Aboriginal Human Resource development. Or in the case of individuals, in having pursued and achieved personal success in their respective career goals. Unity speaks of one heart, one mind, and many hands. In this instance the common thread that brings us together to celebrate tonight is that we all share in aspiring to see Aboriginal citizens participate fully in today’s economy and celebrate success as they work toward achieving their personal career goals. We would like to acknowledge The Board of Directors, Elders, and Leaders for their leadership and guidance to make this event a success. Addressing Workforce needs through Collaboration & Partnership LEADERSHIP EXCELLENCE AWARDS The Leadership Excellence Award celebrates the achievement of individuals who have distinguished themselves as leaders with their contributions toward Aboriginal Human Resource Development and as innovators, trailblazers, and champions of advancing Aboriginal capacity, skill, and artistry. Chief Wilf Adam Lake Babine Nation Chief Wilf Adam has a lengthy history of serving his nation and the broader First Nations communities in British Columbia. Chief Adam has been serving Lake Babine Nation since 1977 in various capacities from Management to Chief. His first term of leadership was in 1983. -

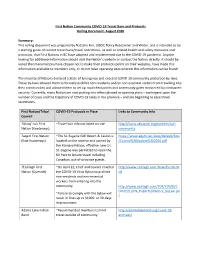

First Nation Community COVID-19 Travel Bans and Protocols Rolling Document- August 2020

First Nation Community COVID-19 Travel Bans and Protocols Rolling Document- August 2020 Summary: This rolling document was prepared by Natasha Kim, UBCIC Policy Researcher and Writer, and is intended to be a starting guide of current travel bans/travel restrictions, as well as related health and safety measures and protocols, that First Nations in BC have adopted and implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Anyone looking for additional information should visit the Nation’s website or contact the Nation directly. It should be noted that many Nations have chosen not to make their protocols public on their websites, have made this information available to members only, or do not have operating sites wherein this information can be found. The majority of Nations declared a State of Emergency and enacted COVID-19 community protection by-laws. These by-laws allowed them to formally prohibit non-residents and/or non-essential visitors from travelling into their communities and allowed them to set up road checkpoints and community gates monitored by contracted security. Currently, many Nation are now putting into effect phased re-opening plans – contingent upon the number of cases and the trajectory of COVID-19 takes in the province – and are beginning to ease travel restrictions. First Nation/Tribal COVID-19 Protocols in Place Links to Community Info Council ?Akisq’ nuk First ~Travel ban info not listed on site http://www.akisqnuk.org/content/our- Nation (Kootenays) community ?aqam First Nation ~The St. Eugene Golf Resort & Casino is https://www.aqam.net/sites/default/files (East Kootenays) located on the reserve and owned by /Council%20Update%202020.pdf the Ktunaxa Nation; effective June 1st, St. -

CSFS Annual General Assembly Booklet

CARRIER SEKANI FAMILY SERVICES CREATING WELLNESS TOGETHER 2016 CSFS ANNUAL GENERAL ASSEMBLY lateral kindness: we respect each another ts’ayewh wigus lhts’eelh’iyh OCTOBER 6 + 7 2016 HOSTED BY THE LAKE BABINE NATION TABLE OF CONTENTS president of the board of directors 4 board of directors 5 welcome from the CEO 6 health services 8 research, primary care, and strategic 36 services child and family services 44 communications 72 privacy and IT 76 financial report 78 sponsor advertisements 91 CARRIER SEKANI FAMILY SERVICES P:1-800-889-6855 987 4TH AVENUE F:1-250-562-2272 PRINCE GEORGE, BC V2L 3H7 WWW.CSFS.ORG BOARD PRESIDENT MESSAGE Hadeeh! Dene’Zeh, Tsa Khu’Zeh, Skhy Zeh! On behalf of the Board of the Directors of Carrier Sekani Family Services , Member Bands and staff, I am pleased to welcome you to the 26th Annual General Assembly. Mussi Cho to Lake Babine Nation for allowing CSFS to meet on our beautiful land to conduct this business. I would like to recognize and thank all of the hereditary Chiefs and also elected Chiefs and Council members for their support and commitment in working in partnership with CSFS to ‘create wellness together’. I further welcome each of the CSFS eleven member First Nations. We are excited to share how we have worked with your communities over the past year, and also hear about exciting innovations you have been working on as well! As we commence on our 26th Annual General Assembly, it is indeed a time to celebrate our accomplishments and reflect on all the good work and lessons learned over our history.