RSI December 2012 Volume IV Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter Eng7 SEL.1-18 Film

À ™ ª ∞ TheÀ™ª∞ Acropolis Restoration News À ¶ ¶ √ À¶¶√ 7 ñ July 2007 The Propylaia and its surroundings from the level of the Parthenon metopes. Photo S. Mavrommatis, June 2007 Ch. Bouras, Theoretical principles of the interventions on the monuments of the Acropolis ª. πoannidou, 2000-2007, The restoration of the Acropolis by the YSMA F. Mallouchou-Tufano, ∂. Petropoulou, Public opinion poll about the restoration of the Acropolis monuments D. Englezos, Protective filling of ancient monuments. The case of the Arrephorion on the Athenian Akropolis ∂. Lembidaki, On the occasion of the new restoration of the temple of Athena Nike. Looking back at the history of the cult statue of Athena Nike C. Hadziaslani, I. Kaimara, A. Leonti, The new educational museum kit “The Twelve Olympian Gods” F. Mallouchou-Tufano, News from the Acropolis F. Mallouchou-Tufano, The restoration of the Erechtheion: 20 years later Theoretical principles of the interventions on the monuments of the Acropolis* 3 Under the circumstances, we were obliged small to large scale. The type of the peripter- lated outlook of Alexandria and Rome. ies and works. The Charter satisfactorily same monument, “syn-anastelosis” a simul- monuments for public purposes. During to manage and to perform interventions of al temple was crystalized, while, from the The boundaries standards set by the Athe- responds to a set of values that the western taneous anastelosis of remains of more than the decades of the 70’s and 80’s, the reuse great importance on monuments of unique standpoint of morphology, a ceaseless perfect- nian monuments will never be surpassed. -

101890 Fr Vol II 432-433

2.PÉNINSULE IBÉRIQUE ET ITALIE PORTUGAL Le Portugal, situé entre 37° et 42° de latitude N ord, repré- sente environ 15 pour cent de la superficie de la péninsuleI bé- rique.1.1 compte 38 pour cent de terres cultivables et 17 pour cent de prairies permanentes. La topographie et le climat sont sembla- bles à ceux de l'Espagne, bien que l'influence océanique y soit plus prononcée. L'été, moyennement chaud dansleszonescôtières, devient torride et sec dans le sud-est du pays. La plus grande partie des précipitations tombe en hiver. Comparé à l'importance du peuplement humain, le nombre de bovins est, au Portugal, inférieur à ce qu'il est dans tout autre pays d'Europe. De grandes étendues présentent en effet des sols et des conditions climatiques plus favorables à l'élevage des ovins qu'à celui des bovins. Les pages qui suivent se rapportent à un. certain nombre de races bovines; il existe aussi à l'intérieur de celles-ci des variétés lo- cales, légèrement différentes, mais dont les caractéres généraux res- tent semblables. TABLEAU 38. RÉPARTITION DES RACES BOVINES PORTLJGAISES Race Pourcentage Mirandesa (Ratinha) 25 Turina (pie noire portugaise) Barrosa A rouquesa 7 Alentejana 6 Mertolenga 6 M inhota 3 Algarvia Brava 1 Autres races et croisements 8 fe.O.Turina ET7.771Barrosa -FIMirandesa ou Ratinha / / / / / / / // / / / Arouqu esa / / / / / / // / / / / / // / // / / / / / / / // / / / / / / // / / / / / // / / / vziAlga rvia / / / / / / / // / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / // / / / / / / / / / // / / / / Alentejana / / / / / / / / / / 111111111 it It / 7/ / Minhota ESE5Mertolenga FIGURE 33. Répartition géographique des races bovines au Portugal. 68 LES BOVINS D'EUROPE Le tableau 38 donne la répartition par ordre d'importance des différentes races portugaises; la figure 33 indique leur distribution géographique. -

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

12 Iczegar Abstracts

12th ICZEGAR ABSTRACTS 12TH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS ON THE ZOOGEOGRAPHY AND ECOLOGY OF GREECE AND ADJACENT REGIONS International Congress on the Zoogeography, Ecology and Evolution of Southeastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean Athens, 18 – 22 June 2012 Published by the HELLENIC ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY, 2012 2nd Edition, September 2012 Editors: A. Legakis, C. Georgiadis & P. Pafilis Proposed reference: A. Legakis, C. Georgiadis & P. Pafilis (eds.) (2012). Abstracts of the International Congress on the Zoogeography, Ecology and Evolution of Southeastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, 18-22 June 2012, Athens, Greece. Hellenic Zoological Society, 230 pp. © 2012, Hellenic Zoological Society ISBN: 978-618-80081-0-6 Abstracts may be reproduced provided that appropriate acknowledgement is given and the reference cited. International Congress on the Zoogeography, Ecology and Evolution of Southeastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean 12th ICZEGAR, 18-22 June 2012, Athens, Greece Organized by the Hellenic Zoological Society Organizing Committee Ioannis Anastasiou Christos Georgiadis Anastasios Legakis Panagiotis Pafilis Aris Parmakelis Costas Sagonas Maria Thessalou-Legakis Dimitris Tsaparis Rosa-Maria Tzannetatou-Polymeni Under the auspices of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens and the Department of Biology of the NKUA PREFACE The 12th International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions (ICZEGAR) is taking place in Athens, 34 years after the inaugural meeting. The congress has become an institution bringing together scientists, students and naturalists working on a wide range of subjects and focusing their research on southeastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean. The congress provides the opportunity to discuss, explore new ideas, arrange collaborations or just meet old friends and make new ones. -

Consequences of Breed Formation on Patterns of Genomic Diversity and Differentiation: the Case of Highly Diverse Peripheral Iberian Cattle Rute R

da Fonseca et al. BMC Genomics (2019) 20:334 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-019-5685-2 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Consequences of breed formation on patterns of genomic diversity and differentiation: the case of highly diverse peripheral Iberian cattle Rute R. da Fonseca1,2* , Irene Ureña3, Sandra Afonso3, Ana Elisabete Pires3,4, Emil Jørsboe2, Lounès Chikhi5,6 and Catarina Ginja3* Abstract Background: Iberian primitive breeds exhibit a remarkable phenotypic diversity over a very limited geographical space. While genomic data are accumulating for most commercial cattle, it is still lacking for these primitive breeds. Whole genome data is key to understand the consequences of historic breed formation and the putative role of earlier admixture events in the observed diversity patterns. Results: We sequenced 48 genomes belonging to eight Iberian native breeds and found that the individual breeds are genetically very distinct with FST values ranging from 4 to 16% and have levels of nucleotide diversity similar or larger than those of their European counterparts, namely Jersey and Holstein. All eight breeds display significant gene flow or admixture from African taurine cattle and include mtDNA and Y-chromosome haplotypes from multiple origins. Furthermore, we detected a very low differentiation of chromosome X relative to autosomes within all analyzed taurine breeds, potentially reflecting male-biased gene flow. Conclusions: Our results show that an overall complex history of admixture resulted in unexpectedly high levels of genomic diversity for breeds with seemingly limited geographic ranges that are distantly located from the main domestication center for taurine cattle in the Near East. This is likely to result from a combination of trading traditions and breeding practices in Mediterranean countries. -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information Supplementary Notes ......................................................................................................................... 2 Supplementary Tables ........................................................................................................................ 7 Supplementary Figures ..................................................................................................................... 13 References ........................................................................................................................................ 20 1 Supplementary notes Note S1. Brief description of the Iberian native cattle breeds sampled in our study The Barrosã cattle are one of the most emblematic of the Iberian Peninsula with their magnificent lyre‐shaped horns and short face. These cattle can be found grazing in the highlands of northwestern Portugal in a collectively managed herding system named ‘vezeira’. They are medium‐sized animals, with concave profile and brown‐blond coat colour. There is marked sexual dimorphism and the males are much darker particularly in the neck and have a characteristic dark ring around the eyes. The herdbook was established in 1985 and is managed by the breeders’ association AMIBA (http://www.amiba.pt). The certified protected designation of origin (PDO) meat ‘Carne Barrosã’ is highly valued due to the intramuscular fat content and large numbers of live Barrosã cattle were exported to England from Oporto in the mid‐19th century until 1920. The milk -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000-700 BCE Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8588693d Author Kontonicolas, MaryAnn Emilia Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000 – 700 BCE A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology by MaryAnn Kontonicolas 2018 © Copyright by MaryAnn Kontonicolas 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Cremation, Society, and Landscape in the North Aegean, 6000 – 700 BCE by MaryAnn Kontonicolas Doctor of Philosophy in Archaeology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor John K. Papadopoulos, Chair This research project examines the appearance and proliferation of some of the earliest cremation burials in Europe in the context of the prehistoric north Aegean. Using archaeological and osteological evidence from the region between the Pindos mountains and Evros river in northern Greece, this study examines the formation of death rituals, the role of landscape in the emergence of cemeteries, and expressions of social identities against the backdrop of diachronic change and synchronic variation. I draw on a rich and diverse record of mortuary practices to examine the co-existence of cremation and inhumation rites from the beginnings of farming in the Neolithic period -

Meta-Analysis of Mitochondrial DNA Reveals Several Population

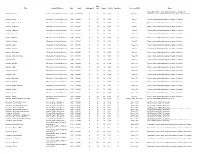

Table S1. Haplogroup distributions represented in Figure 1. N: number of sequences; J: banteng, Bali cattle (Bos javanicus ); G: yak (Bos grunniens ). Other haplogroup codes are as defined previously [1,2], but T combines T, T1’2’3’ and T5 [2] while the T1 count does not include T1a1c1 haplotypes. T1 corresponds to T1a defined by [2] (16050T, 16133C), but 16050C–16133C sequences in populations with a high T1 and a low T frequency were scored as T1 with a 16050C back mutation. Frequencies of I are only given if I1 and I2 have not been differentiated. Average haplogroup percentages were based on balanced representations of breeds. Country, Region Percentages per Haplogroup N Reference Breed(s) T T1 T1c1a1 T2 T3 T4 I1 I2 I J G Europe Russia 58 3.4 96.6 [3] Yaroslavl Istoben Kholmogory Pechora type Red Gorbatov Suksun Yurino Ukrain 18 16.7 72.2 11.1 [3] Ukrainian Whiteheaded Ukrainian Grey Estonia, Byelorussia 12 100 [3] Estonian native Byelorussia Red Finland 31 3.2 96.8 [3] Eastern Finncattle Northern Finncattle Western Finncattle Sweden 38 100.0 [3] Bohus Poll Fjall cattle Ringamala Cattle Swedish Mountain Cattle Swedish Red Polled Swedish Red-and-White Vane Cattle Norway 44 2.3 0.0 0.0 0.0 97.7 [1,4] Blacksided Trondheim Norwegian Telemark Westland Fjord Westland Red Polled Table S1. Cont. Country, Region Percentages per Haplogroup N Reference Breed(s) T T1 T1c1a1 T2 T3 T4 I1 I2 I J G Iceland 12 100.0 [1] Icelandic Denmark 32 100.0 [3] Danish Red (old type) Jutland breed Britain 108 4.2 1.2 94.6 [1,5,6] Angus Galloway Highland Kerry Hereford Jersey White Park Lowland Black-Pied 25 12.0 88.0 [1,4] Holstein-Friesian German Black-Pied C Europe 141 3.5 4.3 92.2 [1,4,7] Simmental Evolene Raetian Grey Swiss Brown Valdostana Pezzata Rossa Tarina Bruna Grey Alpine France 98 1.4 6.6 92.0 [1,4,8] Charolais Limousin Blonde d’Aquitaine Gascon 82.57 Northern Spain 25 4 13.4 [8,9] 1 Albera Alistana Asturia Montana Monchina Pirenaica Pallaresa Rubia Gallega Southern Spain 638 0.1 10.9 3.1 1.9 84.0 [5,8–11] Avileña Berrenda colorado Berrenda negro Cardena Andaluzia Table S1. -

Redalyc.Growth Hormone Alui Polymorphism Analysis in Eight

Archivos de Zootecnia ISSN: 0004-0592 [email protected] Universidad de Córdoba España Reis, C.; Navas, D.; Pereira, M.; Cravador, A. Growth hormone alui polymorphism analysis in eight portuguese bovine breeds. Archivos de Zootecnia, vol. 50, núm. 190, 2001, pp. 41-48 Universidad de Córdoba Córdoba, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=49519007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative GROWTH HORMONE ALUI POLYMORPHISM ANALYSIS IN EIGHT PORTUGUESE BOVINE BREEDS ANçLISIS DEL POLIMORFISMO ALUI DE LA HORMONA DE CRECIMENTO EN OCHO RAZAS BOVINAS PORTUGUESAS Reis, C.1, D. Navas2, M. Pereira3 and A. Cravador1 1Universidade do Algarve. UCTA. Campus de Gambelas. 8000-810 Faro. Portugal. E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] 2Esta•‹o ZootŽcnica Nacional, Departamento de Bovinicultura. Fonte Boa. 2000-763 Vale de SantarŽm. Portugal. E-mail: [email protected] 3Esta•‹o ZootŽcnica Nacional. Departamento de Ovinicultura. Fonte Boa. 2000-763 Vale de SantarŽm. Portugal. E-mail: [email protected] ADDITIONAL KEYWORDS PALABRAS CLAVE ADICIONALES Somatotropin. Polymorphism. Meat production. Somatotropina. Polimorfismo. Producci—n de car- PCR-RFLP. ne. PCR-RFLP. SUMMARY RESUMEN A total of 195 bulls of eight Portuguese beef Un total de 195 bovinos pertenecientes a cattle breeds (Alentejana, Arouquesa, Barros‹, ocho razas productoras de carne portuguesas Maronesa, Marinhoa, Mertolenga, Mirandesa (Alentejana, Arouquesa, Barros‹, Maronesa, and Preta) were genotyped for the GH AluI Marinhoa, Mertolenga, Mirandesa y Preta) fue- polymorphism by the polymerase chain reaction ron genotipados utilizando PCR-RFLP para el and restriction length polymorphism (PCR- polimorfismo CH AluI. -

Um-Maps---G.Pdf

Map Title Author/Publisher Date Scale Catalogued Case Drawer Folder Condition Series or I.D.# Notes Topography, towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gabon - Libreville Service Géographique de L'Armée 1935 1:1,000,000 N 35 10 G1-A F One sheet Cameroon, Gabon, all of Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tomé & Principe Gambia - Jinnak Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 1 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - N'Dungu Kebbe Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 2 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - No Kunda Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 4 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Farafenni Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 5 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kau-Ur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Bulgurk Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 6 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kudang Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Fass Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 7 A Towns, roads, political boundaries for parts of Gambia Gambia - Kuntaur Directorate of Colonial Surveys 1948 1:50,000 N 35 10 G1-B G Sheet 8 Towns, roads, political -

The Truth About Greek Occupied Macedonia

TheTruth about Greek Occupied Macedonia By Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Truth about Greek Occupied Macedonia Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition January 7, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE – Struggle for our own School and Church .......8 1. Macedonian texts written with Greek letters .................................9 2. Educators and renaissance men from Southern Macedonia.........15 3. Kukush – Flag bearer of the educational struggle........................21 4. The movement in Meglen Region................................................33 5. Cultural enlightenment movement in Western Macedonia..........38 6. Macedonian and Bulgarian interests collide ................................41 CHAPTER TWO - Armed National Resistance ..........................47 1. The Negush Uprising ...................................................................47 2. Temporary Macedonian government ...........................................49 -

Photo: Elliniko Panorama Evia Nean, Creating Emporia (Trade Centres)

FREE www.evia.gr Photo: Elliniko Panorama Evia nean, creating emporia (trade centres). Athenian League, especially during the During the rule of Venice, Evia was known The Ippovotes the aristocracy have by Peloponnesian War, apostatise, fighting for their as Negroponte. “Of the seven islands nature now replaced the Mycenaean kings, and their independence, and the island becomes a In early June 1407, Mehmed II The made… Evia is the fifth, narrow…” power, as well as their commercial ties with battlefield. Conqueror takes over Evia, which is (Stefanos Byzantios, under the entry “Sicily”) the Mediterranean civilisations, is reflected in The Evian Commons, a type of confederation renamed Egipoz or Egripos, and becomes the findings from the tomb of the Hegemon in of the city-states of Evia, was founded in 404 BC. the pashalik of Egripos. Evia owes its name to the healthy cattle Leukanti (now divided between the After the battle of Chaironeia in 338 BC, Evia On the 8th of May 1821, the revolution grazing on its fertile land. Eu + bous = good Archaeological Museums of Athens and comes under the rule of Phillip the 2nd and breaks out first in Ksirochori, led by chieftain cattle. Eretria). Macedonian guard are installed in all of its cities. Angelis Govgios, and then in Limni and In the 8th century BC large city states are After the death of Alexander, the island Kymi. It is not long, however, before it is The history of Evia or Avantis or Makris founded, the most important of which are becomes the apple of discord among his stamped out.