Zilcosky on Zischler, 'Kafka Goes to the Movies'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classical Nakedness in British Sculpture and Historical Painting 1798-1840 Cora Hatshepsut Gilroy-Ware Ph.D Univ

MARMOREALITIES: CLASSICAL NAKEDNESS IN BRITISH SCULPTURE AND HISTORICAL PAINTING 1798-1840 CORA HATSHEPSUT GILROY-WARE PH.D UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2013 ABSTRACT Exploring the fortunes of naked Graeco-Roman corporealities in British art achieved between 1798 and 1840, this study looks at the ideal body’s evolution from a site of ideological significance to a form designed consciously to evade political meaning. While the ways in which the incorporation of antiquity into the French Revolutionary project forged a new kind of investment in the classical world have been well-documented, the drastic effects of the Revolution in terms of this particular cultural formation have remained largely unexamined in the context of British sculpture and historical painting. By 1820, a reaction against ideal forms and their ubiquitous presence during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wartime becomes commonplace in British cultural criticism. Taking shape in a series of chronological case-studies each centring on some of the nation’s most conspicuous artists during the period, this thesis navigates the causes and effects of this backlash, beginning with a state-funded marble monument to a fallen naval captain produced in 1798-1803 by the actively radical sculptor Thomas Banks. The next four chapters focus on distinct manifestations of classical nakedness by Benjamin West, Benjamin Robert Haydon, Thomas Stothard together with Richard Westall, and Henry Howard together with John Gibson and Richard James Wyatt, mapping what I identify as -

Featuring Martin Kippenberger's the Happy

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION “K” FEATURING MARTIN KIPPENBERGER’S THE HAPPY END OF FRANZ KAFKA’S ‘AMERIKA’ ACCOMPANIED BY ORSON WELLES’ FILM THE TRIAL AND TANGERINE DREAM’S ALBUM THE CASTLE, IN MILAN FROM 21 FEBRUARY TO 27 JULY 2020 Milan, 31 January 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “K” in its Milan venue from 21 February to 27 July 2020 (press preview on Wednesday 19 February). This project, featuring Martin Kippenberger’s legendary artworkThe Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” accompanied by Orson Welles’ iconic film The Trial and Tangerine Dream’s late electronic album The Castle, is conceived by Udo Kittelmann as a coexisting trilogy. “K” is inspired by three uncompleted and seminal novels by Franz Kafka (1883-1924) ¾Amerika (America), Der Prozess (The Trial), and Das Schloss (The Castle)¾ posthumously published from 1925 to 1927. The unfinished nature of these books allows multiple and open readings and their adaptation into an exhibition project by visual artist Martin Kippenberger, film director Orson Welles, and electronic music band Tangerine Dream, who explored the novels’ subjects and atmospheres through allusions and interpretations. Visitors will be invited to experience three possible creative encounters with Kafka’s oeuvre through a simultaneous presentation of art, cinema and music works, respectively in the Podium, Cinema and Cisterna.“K” proves Fondazione Prada’s intention to cross the boundaries of contemporary art and embrace a vaste cultural sphere, that also comprises historical perspectives and interests in other languages, such as cinema, music, literature and their possible interconnections and exchanges. As underlined by Udo Kittelmann, “America, The Trial, and The Castle form a ‘trilogy of loneliness,’ according to Kafka’s executor Max Brod. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

THE POLITICS of CATASTROPHE in the ART of JOHN MARTIN, FRANCIS DANBY, and DAVID ROBERTS by Christopher J

APOCALYPTIC PROGRESS: THE POLITICS OF CATASTROPHE IN THE ART OF JOHN MARTIN, FRANCIS DANBY, AND DAVID ROBERTS By Christopher James Coltrin A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Susan L. Siegfried, Chair Professor Alexander D. Potts Associate Professor Howard G. Lay Associate Professor Lucy Hartley ©Christopher James Coltrin 2011 For Elizabeth ii Acknowledgements This dissertation represents the culmination of hundreds of people and thousands of hours spent on my behalf throughout the course of my life. From the individuals who provided the initial seeds of inspiration that fostered my general love of learning, to the scholars who helped with the very specific job of crafting of my argument, I have been the fortunate recipient of many gifts of goodness. In retrospect, it would be both inaccurate and arrogant for me to claim anything more than a minor role in producing this dissertation. Despite the cliché, the individuals that I am most deeply indebted to are my two devoted parents. Both my mother and father spent the majority of their lives setting aside their personal interests to satisfy those of their children. The love, stability, and support that I received from them as a child, and that I continue to receive today, have always been unconditional. When I chose to pursue academic interests that seemingly lead into professional oblivion, I probably should have questioned what my parents would think about my choice, but I never did. Not because their opinions didn‟t matter to me, but because I knew that they would support me regardless. -

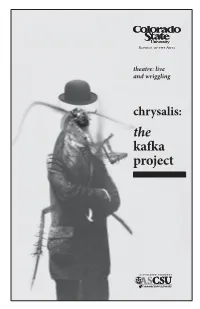

The Kafka Project

theatre: live and wriggling chrysalis: the kafka project CSU Theatre presents chrysalis: the kafka project World Premiere Created by Walt Jones and the Company Original Music by Peter Sommer and James David Directed by Walt Jones Scenic Design by Maggie Seymour The Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival™ 44, part of the Rubenstein Arts Access Program, Lighting Design by Alex Ostwald is generously funded by David and Alice Rubenstein. Costume Design by Janelle Sutton Sound Design by Parker Stegmaier Additional support is provided by the U.S. Department of Education, Projections Design by Nicole Newcomb the Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation, Properties Design by Brittany Lealman The Honorable Stuart Bernstein and Wilma E. Bernstein, and Production Stage Manager, Amy Mills the National Committee for the Performing Arts. Assistant Stage Manager, Tory Sheppard This production is entered in the Kennedy Center American College Theater THE PROGRAMME Festival (KCACTF). The aims of this national theater education program are to identify and promote quality in college-level theater production. To From Amerika . Michael Toland this end, each production entered is eligible for a response by a regional “Report to An Academy” . Tim Werth KCACTF representative, and selected students and faculty are invited to Metamorphosis . Michael Toland, Kat Springer, Michelle Jones, participate in KCACTF programs involving scholarships, internships, grants Nick Holland, Willa Bograd, Sean Cummings and awards for actors, directors, dramaturgs, playwrights, designers, stage “The Country Doctor” . Sean. Cummings, Emma Schenkenberger, managers and critics at both the regional and national levels. Jeff Garland, Willa Bograd, Kat Springer, Kaitlin Jaffke, Tim Werth, Michelle Jones, Nick Holland, Trevor Grattan Productions entered on the Participating level are eligible for inclusion at the Metamorphosis . -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing American Liberalism in Interracial Marriages between American Soldiers and Japanese Women A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Tomoko Tsuchiya Committee in charge: Professor Yen Le Espiritu, Chair Professor Ross Frank Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Denise Ferreira da Silva Professor Lisa Yoneyama 2011 Copyright Tomoko Tsuchiya, 2011 All Rights Reserved The dissertation of Tomoko Tsuchiya is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………...iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………..v Acknowledgements……………………………………………..……..…vi Vita………………………………………………….………………….....ix Abstract of the Dissertation ……...……………………………………….x Introduction………………………………................................................ 1 Part I Love and Violence: Production of the Postwar U.S.-Japan Alliance…….36 Chapter One Dangerous Intimacy: Sexualized Japanese Women during the U.S. Occupation of Japan……...37 Chapter Two Intimacy of Love: Loveable American Soldiers in Cold War Politics.…...68 -

Taboo As a Means of Accessing the Law in Kafka's Works Taylor

Taboo as a Means of Accessing the Law in Kafka’s Works Taylor Sullivan Professor Flenga Ramapo College of New Jersey In a number of Franz Kafka’s works exists a totemic trend—a trend, which involves sexualized gestures carried out between exclusively male characters. The characters’ gestures attempt to achieve fulfillment; however, all are stopped short. Their indefinite impotence, their inability to arrive, mocks a parallel inability on their part to penetrate the law. The mirrored relationships of Kafka’s male characters with sexual fulfillment and nonphysical penetration culminate in “In The Penal Colony.” This short story confirms that Kafka’s male characters exist permanently as the countryman in “Before the Law”—outside of the door, unaware of and 1 unable to access what lies beyond. Such exclusively homoerotic relationships though ignore women. Kafka’s male characters, through gestures that confirm their gender’s unchanging position, leave the positioning of women to question. What Kafka eventually reveals is that if men remain indefinitely before the law, women exist outside of the law entirely. The guiltless attitudes of his female characters confirm their role as permanent outlaws. The root of Kafka’s totemic trend lies in the relationship between the law and prohibition. 2 In his essay, “Before the Law,” Derrida explains that the law is “a prohibited place.” In this 3 4 way, “to not gain access to the law” is “to obey the law.” Conversely, to gain access to the law 5 would be to transgress the very law to which one is gaining access; “the law is prohibition.” Paradoxically then, what the countryman seeks is as much the law as it is prohibition—synonymous beings that exist beyond the door. -

Germ 358 Prof Peters Winter 202! KAFKA in TRANSLATION Course Outline and Itinerary

Germ 358 Prof Peters Winter 202! KAFKA IN TRANSLATION Course Outline and Itinerary PREAMBLE The term “Kafkaesque” has entered many languages, and Franz Kafka is widely recognized as perhaps the “classic” author of the perils and pitfalls of modernity. This course will examine many of the texts which helped make Kafka one of the most celebrated and notorious authors of the past century, and which served to refashion literature and all our notions about what literature can and cannot do. This course will look at the novel The Trial, the short stories The Judgement, The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, The Hunger Artist etc., as well as short prose texts and passages from his diaries and letters. Films and other medial adaptations and representations of Kafka’s works will also be part of the course, as will the Kafka criticism of such authors as Gunther Anders, Elias Canetti, and Walter Benjamin. Political, feminist, theological, Judaicist, as well as contemporary “new historicist” and “cultural materialist” approaches to Kafka will also be considered. This course is given in English. FORMAT This course is in a lecture format and in a blend of fixed and flexible presentation. The lectures will be made available in audio format on the day they are scheduled to be given with the possibility for the subsequent submission of questions and comments by the class. The lectures will be recorded and available in their entirety on mycourses. SELF-PRESENTATION (Selbstdarstellung) I do not as a general rule mediatize myself, and for reasons of deeply held religious and philosophical conviction regard the generation of the simulacra of living human presence though Skype or Zoom as idolatrous and highly problematic. -

Kafka's Travels

Kafka’s Travels Kafka’s Travels Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing John Zilcosky palgrave macmillan KAFKA’S TRAVELS Copyright © John Zilcosky, 2003. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published 2003 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York,N.Y.10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS. Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-4039-6767-1 ISBN 978-1-137-07637-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-137-07637-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zilcosky, John. Kafka’s travels : exoticism, colonialism, and the traffic of writing / John Zilcosky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-312-23281-8 1. Kafka, Franz, 1883–1924—Criticism and interpretation. 2. Kafka, Franz, 1883–1924—Journeys. I. Title. PT2621.A26 Z36 2002 833’.912—dc21 2002029082 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Letra Libre, Inc. First edition: February 2003 10987654321 To my parents and the memory of Charles Bernheimer Contents Acknowledgements ix List -

Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing by John Zilcosky

UC Berkeley TRANSIT Title BOOK REVIEW: Kafka’s Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing by John Zilcosky Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/45539222 Journal TRANSIT, 2(1) Author Gerhardt, Christina Publication Date 2005 DOI 10.5070/T721009704 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California John Zilcosky. Kafka’s Travels: Exoticism, Colonialism, and the Traffic of Writing. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. Pp. xvi, 289. Cloth $79.95. Paper $26.95. As much a meditation on the relationship among Franz Kafka’s writing, travel and travel writing, and concomitant subject matters – such as fin de siècle exoticism, colonialism and imperialism, as well as railroad expansions, travel guides and adventure books – Zilcosky’s well-researched volume Kafka’s Travels also considers the arrival and role of technologies as varied as photography, film, telephones, and telegrams vis-à-vis Kafkas’ writings. Kafka, as Zilcosky tells us on the opening page of his book, “never moved from Prague until the final year of his life and, yes, his travels were limited to short trips throughout Europe.” Why then a study of Kafka’s Travels? Because not only was Kafka an avid reader of books about travel, such as colonial travel stories, but he also avidly traveled, as Zilcosky convincingly argues, through his texts, both the ones he read and the ones he wrote. Zilcosky analyzes the well-known novels America, The Trial, and The Castle, and short stories, such as The Metamorphosis, “In the Penal Colony,” and “The Hunter Gracchus.” He also sheds new light on Kafka’s Letters to Milena. -

Kafka and the Moving Image

Call For Papers Kafka And The Moving Image His thinking, as his wonderful diary shows, was generally done in the form of images (Brod, Franz Kafka Biography 52) The cinematic quality of Kafka's prose, as noted by his biographer Max Brod, has been clear to many of the most important commentators on 20 th century art. Theodor Adorno, for one, claimed that Kafka's texts agitate the reader to the point he fears they will "shoot towards him like a locomotive in a three- dimensional film." Walter Benjamin, meanwhile, compares the Kafkaesque situation with that of the alienated subject watching himself on film. Nevertheless, the idea of "imaging" the Kafkaesque was denied by many – first and foremost by Kafka himself, who famously urged his publisher to avoid an image of the insect on the cover of "Die Verwandlung". Be that as it may, it is unlikely that Kafka, a central progenitor of 20 th century art and thought, can be fully understood without reference to the revolutionary artistic medium of his century: cinema. The integration of Kafka and the moving image has thus materialized in adaptations, documentaries, biographical films, installations and otherwise. Several thinkers have vaguely referred to this integration on a theoretical level: In his Cinema 1, Gilles Deleuze – a pivotal thinker on both Kafka and the moving image – asks whether Kafka's mixture of "phantom machines" is not also "the whole history of the cinema?" while Walter Benjamin describes Kafka's craft as divesting "the humane gesture of its traditional supports" to have "a subject for reflection without end" – a description that could as well be ascribed to the craft of film-making. -

Kafka in Kanada Von Lara Pehar

Kafka-Atlas Kafka in Kanada von Lara Pehar Matamorphosis-Ausstellung beim Nuit-Blanche-Festival Porträt Innerhalb des kanadischen akademischen Bereiches ist Franz Kafka ein etablierter kanonischer Autor. Seine Werke werden in unterschiedlichen Disziplinen erforscht und gelehrt: in der Germanistik, und der Slawistik, und auch in vergleichender Literaturwissenschaft, sowohl in der Judaistik, als auch in Diasporastudien und in Jura. Auch im kulturellen Leben Kanadas nimmt der Prager Autor eine ikonische Funktion als Philosoph ein. Die berühmtesten seiner Werke wurden für die Bühne adaptiert oder zu Hörspielen verarbeitet; politisch motivierte Filme und künstlerische Projekte betten die bürokratische Aspekte seiner Werke ein und heben die subjektive Erfahrung von Kafkas Helden hervor. kafkaesk „Kafkaesque“ ist ein sehr häufig verwendeter Begriff in der Umgangssprache und insbesondere im Journalismus. Ein Eintrag dafür erscheint sogar im Canadian Oxford Dictionary, was den enormen Symbolwert Kafkas in Kanada vermuten lässt. Die Assoziationen des Attributs „kafkaesk“ sind auch in Kanada vielfältig: bedrohlich, grotesk, rätselhaft, paradox, usw. Dennoch wird seine bürokratische Dimension am meisten wahrgenommen. In den Medien kommt der Begriff in den letzten Jahren immer häufiger zum Einsatz, besonders im Zusammenhang mit der Politik der kanadischen Regierung bezüglich Staatsbürgerschaft, Einwanderung und Überwachung terroristischer Aktivitäten im Lande als Folge der Terroranschläge am 11. September 2001. Diese Tendenz veranschaulichen die Schlagzeilen in den Zeitungen: „After Kafkaesque hunt, Indian status and citizenship both out of reach for desperate Ontario mom“ (The National Post, 25. Juli, 2013); „Kafkaesque bureaucracy denies citizenship to legitimate Canadians“ (The Vancouver Observer, 2. September, 2012); „Canada’s K: Mohammad Mahjoub’s Kafkaesque ordeal“ (Pacific Free Press, 24. Oktober, 2013); „Campaign against ‚Kafkaesque justice’ in Canada“ (Centre for Media Alternatives Quebec, 12.