Constructing Kafka, Deconstructing the Self in French Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

Governs the Making of Photocopies Or Other Reproductions of Copyrighted Materials

Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions The Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If electronic transmission of reserve material is used for purposes in excess of what constitutes "fair use," that user may be liable for copyright infringement. OXFORD WORLD'S CLASSICS OXFORD WORLD'S CLASSICS For over 100 years Oxford World'J Classics have brought readers closer to the morld's great litera·ture. Nom mith over 700 titles-from the 4,ooo-year-old myths ofMesopotamia to the FRANZ KAFKA twentieth century's greatest IW1'els-the series makes available lesser-known as me" as celebrated mriting. The pocket-sized hardbacks ofthe early years contained A Hunger Artist ill/roductiolls by Virginill Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, alld other literalJlfigures mhich eIlriched the experience ofreading. and Other Stories Today the set'ies is recogllizedfor ilsfine scholarship and reliability ill texts that span world liurature, drama and poetry, religion, philosophy, lind politics. Each edition includes perceptive commel/t.ary and essential background information to meet the changing needs ofreaders. Translated by JOYCE CRICK With an Introduction and Notes by RITCHIE ROBERTSON OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 56 A Hunger Artist: Four Stories A Hunger Artist 57 the wider world would be concerned with the affair after all-where, the personal direction of the performer himself, nowadays it is as I shall keep repeating, it has no jurisdiction-I shall not, I admit, completely impossible. -

Featuring Martin Kippenberger's the Happy

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION “K” FEATURING MARTIN KIPPENBERGER’S THE HAPPY END OF FRANZ KAFKA’S ‘AMERIKA’ ACCOMPANIED BY ORSON WELLES’ FILM THE TRIAL AND TANGERINE DREAM’S ALBUM THE CASTLE, IN MILAN FROM 21 FEBRUARY TO 27 JULY 2020 Milan, 31 January 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “K” in its Milan venue from 21 February to 27 July 2020 (press preview on Wednesday 19 February). This project, featuring Martin Kippenberger’s legendary artworkThe Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” accompanied by Orson Welles’ iconic film The Trial and Tangerine Dream’s late electronic album The Castle, is conceived by Udo Kittelmann as a coexisting trilogy. “K” is inspired by three uncompleted and seminal novels by Franz Kafka (1883-1924) ¾Amerika (America), Der Prozess (The Trial), and Das Schloss (The Castle)¾ posthumously published from 1925 to 1927. The unfinished nature of these books allows multiple and open readings and their adaptation into an exhibition project by visual artist Martin Kippenberger, film director Orson Welles, and electronic music band Tangerine Dream, who explored the novels’ subjects and atmospheres through allusions and interpretations. Visitors will be invited to experience three possible creative encounters with Kafka’s oeuvre through a simultaneous presentation of art, cinema and music works, respectively in the Podium, Cinema and Cisterna.“K” proves Fondazione Prada’s intention to cross the boundaries of contemporary art and embrace a vaste cultural sphere, that also comprises historical perspectives and interests in other languages, such as cinema, music, literature and their possible interconnections and exchanges. As underlined by Udo Kittelmann, “America, The Trial, and The Castle form a ‘trilogy of loneliness,’ according to Kafka’s executor Max Brod. -

1 Franz Kafka (1883-1924) the Metamorphosis (1915)

1 Franz Kafka (1883-1924) The Metamorphosis (1915) Translated by Ian Johnston, Malaspina University-College I One morning, as Gregor Samsa was waking up from anxious dreams, he discovered that, in his bed, he had been changed into a monstrous vermin. He lay on his armour-hard back and saw, as he lifted his head up a little, his brown, arched abdomen divided up into rigid bow-like sections. From this height the blanket, just about ready to slide off completely, could hardly stay in place. His numerous legs, pitifully thin in comparison to the rest of his circumference, flickered helplessly before his eyes. “What’s happened to me,” he thought. It was no dream. His room, a proper room for a human being, only somewhat too small, lay quietly between the four well-known walls. Above the table, on which an unpacked collection of sample cloth goods was spread out—Samsa was a travelling salesman—hung the picture which he had cut out of an illustrated magazine a little while ago and set in a pretty gilt frame. It was a picture of a woman with a fur hat and a fur boa. She sat erect there, lifting up in the direction of the viewer a solid fur muff into which her entire forearm had disappeared. Gregor’s glance then turned to the window. The dreary weather—the rain drops were falling audibly down on the metal window ledge—made him quite melancholy. “Why don’t I keep sleeping for a little while longer and forget all this foolishness,” he thought. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

A University of Sussex Phd Thesis Available Online Via Sussex

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Peripheral Vision: The Miltonic in Victorian Painting, Poetry, and Prose, 1825–1901 Laura Fox Gill Submitted for the examination of Doctor of Philosophy in English University of Sussex May 2017 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: . UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX LAURA FOX GILL DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PERIPHERAL VISION: THE MILTONIC IN VICTORIAN PAINTING, POETRY, AND PROSE, 1825–1901 SUMMARY This thesis explores the influence of John Milton on the edges of Victorian culture, addressing temporal, geographical, bodily, and sexual thresholds in Victorian poetry, painting, and prose. Where previous studies of Milton’s Victorian influence have focused on the poetic legacy of Paradise Lost, this project identifies traces of Miltonic concepts across aesthetic borders, analysing an interdisciplinary cultural sample in order to state anew Milton’s significance in the period between British Romanticism and early twentieth-century critical debates about the value of Paradise Lost. -

The Fate of Invention in Late 19 Century French Literature

The Fate of Invention in Late 19th Century French Literature Ana I. Oancea Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 ©2014 Ana I. Oancea All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Fate of Invention in Late 19th Century French Literature Ana I. Oancea This dissertation reads the novels of Jules Verne, Albert Robida, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam and Emile Zola, investigating the representation of inventors who specialize in electricity. The figure appears as the intersection of divergent literary movements: Zola, the father of Naturalism and leading proponent of a ‘scientific’ approach to literature, Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, decadent playwright and novelist, Robida, leading caricaturist and amateur historian, and Verne, prominent figure in the emerging genre of anticipation, all develop the inventor character as one who succeeds in realizing key technological aspirations of the 19th century. The authors, however, take a dim view of his activity. Studying the figure of the inventor allows us to gain insight into fundamental 19th century French anxieties over the nation’s progress in science and technology, its national identity, and international standing. The corpus casts science as a pillar of French culture and a modern expression of human creativity, but suggests that social control over how progress is achieved is more important than pure advancement, no matter the price of attaining control. There is a great desire for progress in this period, but as society’s dependence on scientific advancement is becoming apparent, so is its being ignorant of the means through which to achieve it. -

NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946

INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL (NUREMBERG) Judgment of 1 October 1946 Page numbers in braces refer to IMT, judgment of 1 October 1946, in The Trial of German Major War Criminals. Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Germany , Part 22 (22nd August ,1946 to 1st October, 1946) 1 {iii} THE INTERNATIONAL MILITARY TRIBUNAL IN SESSOIN AT NUREMBERG, GERMANY Before: THE RT. HON. SIR GEOFFREY LAWRENCE (member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) President THE HON. SIR WILLIAM NORMAN BIRKETT (alternate member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) MR. FRANCIS BIDDLE (member for the United States of America) JUDGE JOHN J. PARKER (alternate member for the United States of America) M. LE PROFESSEUR DONNEDIEU DE VABRES (member for the French Republic) M. LE CONSEILER FLACO (alternate member for the French Republic) MAJOR-GENERAL I. T. NIKITCHENKO (member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) LT.-COLONEL A. F. VOLCHKOV (alternate member for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics) {iv} THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND, AND THE UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLICS Against: Hermann Wilhelm Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Robert Ley, Wilhelm Keitel, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Alfred Rosenberg, Hans Frank, Wilhelm Frick, Julius Streicher, Walter Funk, Hjalmar Schacht, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, Karl Dönitz, Erich Raeder, Baldur von Schirach, Fritz Sauckel, Alfred Jodl, Martin -

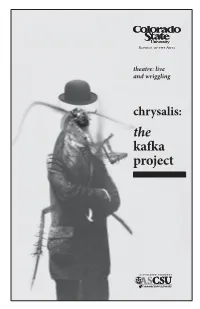

The Kafka Project

theatre: live and wriggling chrysalis: the kafka project CSU Theatre presents chrysalis: the kafka project World Premiere Created by Walt Jones and the Company Original Music by Peter Sommer and James David Directed by Walt Jones Scenic Design by Maggie Seymour The Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival™ 44, part of the Rubenstein Arts Access Program, Lighting Design by Alex Ostwald is generously funded by David and Alice Rubenstein. Costume Design by Janelle Sutton Sound Design by Parker Stegmaier Additional support is provided by the U.S. Department of Education, Projections Design by Nicole Newcomb the Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation, Properties Design by Brittany Lealman The Honorable Stuart Bernstein and Wilma E. Bernstein, and Production Stage Manager, Amy Mills the National Committee for the Performing Arts. Assistant Stage Manager, Tory Sheppard This production is entered in the Kennedy Center American College Theater THE PROGRAMME Festival (KCACTF). The aims of this national theater education program are to identify and promote quality in college-level theater production. To From Amerika . Michael Toland this end, each production entered is eligible for a response by a regional “Report to An Academy” . Tim Werth KCACTF representative, and selected students and faculty are invited to Metamorphosis . Michael Toland, Kat Springer, Michelle Jones, participate in KCACTF programs involving scholarships, internships, grants Nick Holland, Willa Bograd, Sean Cummings and awards for actors, directors, dramaturgs, playwrights, designers, stage “The Country Doctor” . Sean. Cummings, Emma Schenkenberger, managers and critics at both the regional and national levels. Jeff Garland, Willa Bograd, Kat Springer, Kaitlin Jaffke, Tim Werth, Michelle Jones, Nick Holland, Trevor Grattan Productions entered on the Participating level are eligible for inclusion at the Metamorphosis . -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing American Liberalism in Interracial Marriages between American Soldiers and Japanese Women A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Tomoko Tsuchiya Committee in charge: Professor Yen Le Espiritu, Chair Professor Ross Frank Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Denise Ferreira da Silva Professor Lisa Yoneyama 2011 Copyright Tomoko Tsuchiya, 2011 All Rights Reserved The dissertation of Tomoko Tsuchiya is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………...iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………..v Acknowledgements……………………………………………..……..…vi Vita………………………………………………….………………….....ix Abstract of the Dissertation ……...……………………………………….x Introduction………………………………................................................ 1 Part I Love and Violence: Production of the Postwar U.S.-Japan Alliance…….36 Chapter One Dangerous Intimacy: Sexualized Japanese Women during the U.S. Occupation of Japan……...37 Chapter Two Intimacy of Love: Loveable American Soldiers in Cold War Politics.…...68 -

November/December 2012

From the Office By Daniel D. Skwire His complaints about his duties were epic, but Kafka clearly drew satisfaction from working his day job at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute of the Kingdom of Bohemia in Prague. ITTLE KNOWN DURING HIS LIFETIME, ghastly machine to torture and execute his prisoners. And in Franz Kafka has come to be recognized as one of The Trial, a man must defend himself in court without being the greatest writers of the 20th century. His works informed of the crime he has been accused of committing. These include some of the most disturbing and enduring portraits of disillusionment, anxiety, and despair anticipate the images of modern fiction. The hero of The Metamor- subsequent horrors of mid-20th-century war and inhumanity. phosis, for example, awakens one morning to find he has been Many of the details of Kafka’s own life are scarcely more Ltransformed into a giant insect. Kafka’s short story “In the Penal cheerful. A sickly individual, he struggled with tuberculosis and Colony” features an officer in a prison camp who maintains a other illnesses before dying at the age of 40. His relationships 20 CONTINGENCIES NOV | DEC.12 WWW.CONTINGENCIES.ORG of Franz Kafka Kafka's desk at the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute in Prague with women were unsuccessful, and he never married despite their occupations. An examination of Kafka’s insurance career being engaged on several occasions. He lived with his parents humanizes him and sheds light on his writing by showing his for most of his life and complained bitterly that his work in the dedication, accomplishments, and sense of humor alongside his insurance profession kept him from his true calling of writing—a many frustrations. -

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Ebook Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Paperback: 488 pages Publisher: Schocken Books Inc.; Reprint edition (November 14, 1995) Language: English ISBN-10: 0805210555 ISBN-13: 978-0805210552 Product Dimensions:5.2 x 1 x 8 inches ISBN10 0805210555 ISBN13 978-0805210 Download here >> Description: The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka’s stories, from the classic tales such as “The Metamorphosis,” “In the Penal Colony,” and “A Hunger Artist” to shorter pieces and fragments that Max Brod, Kafka’s literary executor, released after Kafka’s death. With the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka’s narrative work is included in this volume. Hello All,I recently purchased this book in faith, though I was also frustrated by the lack of information in the book description. So, I will provide here for you the table of contents so that whoever purchases this book from now on can know exactly what they are getting:(By the way, the book is beautifully new & well designed, with the edges of the pages torn, not cut.)When it says the complete stories, it means it. The foreword assures that the book contains all of the fiction that Kafka committed to publication during his lifetime. That meas his novels, which he did NOT intend to be published but left note in his will to be destroyed, are NOT included: The Trial, America, The Castle.