Franz Kafka's Amerika

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Featuring Martin Kippenberger's the Happy

FONDAZIONE PRADA PRESENTS THE EXHIBITION “K” FEATURING MARTIN KIPPENBERGER’S THE HAPPY END OF FRANZ KAFKA’S ‘AMERIKA’ ACCOMPANIED BY ORSON WELLES’ FILM THE TRIAL AND TANGERINE DREAM’S ALBUM THE CASTLE, IN MILAN FROM 21 FEBRUARY TO 27 JULY 2020 Milan, 31 January 2020 – Fondazione Prada presents the exhibition “K” in its Milan venue from 21 February to 27 July 2020 (press preview on Wednesday 19 February). This project, featuring Martin Kippenberger’s legendary artworkThe Happy End of Franz Kafka’s “Amerika” accompanied by Orson Welles’ iconic film The Trial and Tangerine Dream’s late electronic album The Castle, is conceived by Udo Kittelmann as a coexisting trilogy. “K” is inspired by three uncompleted and seminal novels by Franz Kafka (1883-1924) ¾Amerika (America), Der Prozess (The Trial), and Das Schloss (The Castle)¾ posthumously published from 1925 to 1927. The unfinished nature of these books allows multiple and open readings and their adaptation into an exhibition project by visual artist Martin Kippenberger, film director Orson Welles, and electronic music band Tangerine Dream, who explored the novels’ subjects and atmospheres through allusions and interpretations. Visitors will be invited to experience three possible creative encounters with Kafka’s oeuvre through a simultaneous presentation of art, cinema and music works, respectively in the Podium, Cinema and Cisterna.“K” proves Fondazione Prada’s intention to cross the boundaries of contemporary art and embrace a vaste cultural sphere, that also comprises historical perspectives and interests in other languages, such as cinema, music, literature and their possible interconnections and exchanges. As underlined by Udo Kittelmann, “America, The Trial, and The Castle form a ‘trilogy of loneliness,’ according to Kafka’s executor Max Brod. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

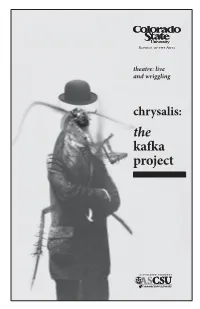

The Kafka Project

theatre: live and wriggling chrysalis: the kafka project CSU Theatre presents chrysalis: the kafka project World Premiere Created by Walt Jones and the Company Original Music by Peter Sommer and James David Directed by Walt Jones Scenic Design by Maggie Seymour The Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival™ 44, part of the Rubenstein Arts Access Program, Lighting Design by Alex Ostwald is generously funded by David and Alice Rubenstein. Costume Design by Janelle Sutton Sound Design by Parker Stegmaier Additional support is provided by the U.S. Department of Education, Projections Design by Nicole Newcomb the Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation, Properties Design by Brittany Lealman The Honorable Stuart Bernstein and Wilma E. Bernstein, and Production Stage Manager, Amy Mills the National Committee for the Performing Arts. Assistant Stage Manager, Tory Sheppard This production is entered in the Kennedy Center American College Theater THE PROGRAMME Festival (KCACTF). The aims of this national theater education program are to identify and promote quality in college-level theater production. To From Amerika . Michael Toland this end, each production entered is eligible for a response by a regional “Report to An Academy” . Tim Werth KCACTF representative, and selected students and faculty are invited to Metamorphosis . Michael Toland, Kat Springer, Michelle Jones, participate in KCACTF programs involving scholarships, internships, grants Nick Holland, Willa Bograd, Sean Cummings and awards for actors, directors, dramaturgs, playwrights, designers, stage “The Country Doctor” . Sean. Cummings, Emma Schenkenberger, managers and critics at both the regional and national levels. Jeff Garland, Willa Bograd, Kat Springer, Kaitlin Jaffke, Tim Werth, Michelle Jones, Nick Holland, Trevor Grattan Productions entered on the Participating level are eligible for inclusion at the Metamorphosis . -

The British Navy from Within

THE BRITISH NAVY FROM WITHIN BY "LOWER DECK." ll(llilMIHIIIIIIIMIHiHi||i)IWII»IIIHI(lllill^aMipF-'#' Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/britishnavyfromwOOexrorich Hodder & Stougl)ton*s War Publications General Yon Bernhardi HOW GERMANY MAKES WAR. By General Von Bernhardi 2/' net (paper) I 2/6 net (cloth). CAVALRY. By General Von Bernhardi. 2/' net (paper) ; 2/6 net (cloth). " Diiifofm with Bemhardi's " How Germany Makes War THE REALITY OF WAR. A companion to ** Clauscwitz." By Major Stewart L. Murray. 2/' net (paper) j 2/6 net (cloth). THE NATION IN ARMS. By Field^Marshal Von der Goltz. 2}' net (paper) j 2/6 net (cloth). THE GERMAN ARMY FROM WITHIN. By a British Officer who has served in it. 2/- net (paper) ; 2J6 net (cloth). THE RUSSIAN ARMY FROM WITHIN. By one who knows it from the inside. 2/^ net (paper); 2/6 net (cloth). THE BRITISH ARMY FROM WITHIN. By one who has served in it. 2/' net (paper) j 2/6 net (cloth). THE BRITISH NAVY FROM WITHIN. 2/^ net (paper); 2/6 net (cloth). THE FRENCH ARMY FROM WITHIN. By-Ex^Trooper.** 2/' net (paper) J 2/6 net (cloth). THE GERMAN SPY SYSTEM FROM WITHIN. 2/. net (paper) ; 2/6 net (cloth). THE CZAR AND HIS PEOPLE. 2/- net (paper) ; 2/6 net (cloth). The French View of Modern War. FRANCE AND THE NEXT WAR, By Commandant J. Colin. 2/' net (paper); 2/6 net (cloth). THE BRITISH NAVY FROM WITHIN Hoddgr & Stougl)ton*s War Publications The "Daily Telegraph" War Books Price One Shilling each net, cloth. -

Evolutionary Socialism

Eduard Bernstein EVOLUTIONARY EVOLUTIONARY SOCIALISM EDUARD BERNSTEIN EVOLUTIONARY SOCIALISM A Criticism and Affirmation INTRODUCTION BY SIDNEY HOOK SCHOCKEN BOOKS • NEW YORK Die Voraussetzungen des Sozialismus und die Aufgaben der Sozialdemokratie Translated by Edith C. Harvey First schocken Paperback Edition 196 Fourth printing, 1967 HX BS53 Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 61-16649 Manufactured in the United States of America CONTENTS Introduction by Sidney Hook vii Preface to English Edition - - - xxi Preface - xxiii I. The Fundamental Doctrines of Marxist Socialism - - - i (a) The Scientific Elements of Marxism - i (6) The Materialist Interpretation of History and Historic Necessity 6 (c) The Marxist Doctrine of Class War and of the Evolution of Capital - - - 18 II. The Economic Development of Modern Society 28 (a) On the Meaning of the Marxist Theory of Value 28 (6) The Distribution of Wealth in the Modern Community 40 (c) The Classes of Enterprises in the Produc- tion and Distribution of Wealth - - 54 (d) Crises and Possibilities of Adjustment in Modern Economy 73 III. The Tasks and Possibilities of Social Democracy 95 (a) The Political and Economic Preliminary Conditions of Socialism - - - 95 (6) The Economic Capacities of Co-operative Associations - - - - - -109 (c) Democracy and Socialism - - - 135 (d) The Most Pressing Problems of Social Democracy - - - - - - 165 Conclusion : Ultimate Aim and Tendency— Kant against Cant ... - 200 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/evolutionarysociaOObern INTRODUCTION Eduard Bernstein is the father of socialist "revision- ism." The term "revisionism," however, is almost as ambiguous as the term "socialism." Particularly today, when the political ties of the communist world are being fractured by charges of "revisionism," it becomes necessary to distinguish the various move- ments and families of doctrine which are encompassed by the name. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Cold War Love: Producing American Liberalism in Interracial Marriages between American Soldiers and Japanese Women A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Tomoko Tsuchiya Committee in charge: Professor Yen Le Espiritu, Chair Professor Ross Frank Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Denise Ferreira da Silva Professor Lisa Yoneyama 2011 Copyright Tomoko Tsuchiya, 2011 All Rights Reserved The dissertation of Tomoko Tsuchiya is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………...iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………..v Acknowledgements……………………………………………..……..…vi Vita………………………………………………….………………….....ix Abstract of the Dissertation ……...……………………………………….x Introduction………………………………................................................ 1 Part I Love and Violence: Production of the Postwar U.S.-Japan Alliance…….36 Chapter One Dangerous Intimacy: Sexualized Japanese Women during the U.S. Occupation of Japan……...37 Chapter Two Intimacy of Love: Loveable American Soldiers in Cold War Politics.…...68 -

Taboo As a Means of Accessing the Law in Kafka's Works Taylor

Taboo as a Means of Accessing the Law in Kafka’s Works Taylor Sullivan Professor Flenga Ramapo College of New Jersey In a number of Franz Kafka’s works exists a totemic trend—a trend, which involves sexualized gestures carried out between exclusively male characters. The characters’ gestures attempt to achieve fulfillment; however, all are stopped short. Their indefinite impotence, their inability to arrive, mocks a parallel inability on their part to penetrate the law. The mirrored relationships of Kafka’s male characters with sexual fulfillment and nonphysical penetration culminate in “In The Penal Colony.” This short story confirms that Kafka’s male characters exist permanently as the countryman in “Before the Law”—outside of the door, unaware of and 1 unable to access what lies beyond. Such exclusively homoerotic relationships though ignore women. Kafka’s male characters, through gestures that confirm their gender’s unchanging position, leave the positioning of women to question. What Kafka eventually reveals is that if men remain indefinitely before the law, women exist outside of the law entirely. The guiltless attitudes of his female characters confirm their role as permanent outlaws. The root of Kafka’s totemic trend lies in the relationship between the law and prohibition. 2 In his essay, “Before the Law,” Derrida explains that the law is “a prohibited place.” In this 3 4 way, “to not gain access to the law” is “to obey the law.” Conversely, to gain access to the law 5 would be to transgress the very law to which one is gaining access; “the law is prohibition.” Paradoxically then, what the countryman seeks is as much the law as it is prohibition—synonymous beings that exist beyond the door. -

Zilcosky on Zischler, 'Kafka Goes to the Movies'

H-German Zilcosky on Zischler, 'Kafka Goes to the Movies' Review published on Monday, September 1, 2003 Hanns Zischler. Kafka Goes to the Movies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. xiv + 143 pp. $30.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-226-98671-5. Reviewed by John Zilcosky (Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, University of Toronto.) Published on H-German (September, 2003) Boundless Entertainment? Boundless Entertainment? There are at least three ways to read this book, which first appeared as Kafka geht ins Kino in 1996: as a discussion of the significance of film and new media for Kafka's writing; as a mission of cultural recovery, including never-before-published archival film footage; and as a "mad and beautiful project" (Paul Auster) that combines autobiography, detective novel, art collage, and literary scholarship. In the first sense the book fails, but in the other two it succeeds in surprising, original ways. To begin with the last point: Zischler's book opens unusually, with a series of images including a spectacular 1914 photograph of Prague's Bio Lucerna cinema. The small "1" in the bottom right corner alerts us to the fact that this photograph has a footnote, and we thus begin Zischler's strange readerly trip. We start flipping pages, like the attendant Kafka noticed at the Kaiser Panorama, from front to back, image to word, and vice-versa. Zischler's intellectual collage develops toward metaphysical detective fiction--we can see why Auster liked it!--when the main text opens: "I was working on a television movie about Kafka in 1978 when I first came across the notes on the cinema in his early diaries and letters." This leisurely curiosity of the actor in a Kafka movie eventually developed into an obsession: into "regular detective work" that took Zischler on the route of Kafka's early bachelor trips with Max Brod (Munich, Milan, Paris) in search of old cinemas and films. -

Germ 358 Prof Peters Winter 202! KAFKA in TRANSLATION Course Outline and Itinerary

Germ 358 Prof Peters Winter 202! KAFKA IN TRANSLATION Course Outline and Itinerary PREAMBLE The term “Kafkaesque” has entered many languages, and Franz Kafka is widely recognized as perhaps the “classic” author of the perils and pitfalls of modernity. This course will examine many of the texts which helped make Kafka one of the most celebrated and notorious authors of the past century, and which served to refashion literature and all our notions about what literature can and cannot do. This course will look at the novel The Trial, the short stories The Judgement, The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, The Hunger Artist etc., as well as short prose texts and passages from his diaries and letters. Films and other medial adaptations and representations of Kafka’s works will also be part of the course, as will the Kafka criticism of such authors as Gunther Anders, Elias Canetti, and Walter Benjamin. Political, feminist, theological, Judaicist, as well as contemporary “new historicist” and “cultural materialist” approaches to Kafka will also be considered. This course is given in English. FORMAT This course is in a lecture format and in a blend of fixed and flexible presentation. The lectures will be made available in audio format on the day they are scheduled to be given with the possibility for the subsequent submission of questions and comments by the class. The lectures will be recorded and available in their entirety on mycourses. SELF-PRESENTATION (Selbstdarstellung) I do not as a general rule mediatize myself, and for reasons of deeply held religious and philosophical conviction regard the generation of the simulacra of living human presence though Skype or Zoom as idolatrous and highly problematic. -

Biting Back: Racism, Homophobia and Vampires in Bram Stoker, Anne Rice and Alan Ball Alyssa Gammello Long Island University, [email protected]

Long Island University Digital Commons @ LIU Undergraduate Honors College Theses 2016- LIU Post 2018 Biting Back: Racism, Homophobia and Vampires in Bram Stoker, Anne Rice and Alan Ball Alyssa Gammello Long Island University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liu.edu/post_honors_theses Recommended Citation Gammello, Alyssa, "Biting Back: Racism, Homophobia and Vampires in Bram Stoker, Anne Rice and Alan Ball" (2018). Undergraduate Honors College Theses 2016-. 47. https://digitalcommons.liu.edu/post_honors_theses/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the LIU Post at Digital Commons @ LIU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors College Theses 2016- by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ LIU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Biting Back: Racism, Homophobia and Vampires in Bram Stoker, Anne Rice and Alan Ball An Honors Program Thesis by Alyssa Gammello Fall 2018 English Department ____________________________ Faculty Advisor, Dr. Thomas Fahy ____________________________ Faculty Reader Dr. John Lutz December 3rd, 2018 1 Table of Contents Introduction and Overview 3 Chapter 1: Dracula and Stoker’s Bloody Depictions 10 Dracula’s Women: The Dangers of Sexuality in Victorian Culture Dangerous Others: Ethnicity in Dracula Chapter 2: Interview with the Vampire and the New Family 33 Twisted Families and Lovers: Sexuality in Interview with the Vampire The Vampire as Slave: Rice’s Plantation Life and the Other Vampire Chapter 3: The Modern Vampire’s Metaphor in True Blood 49 Alan Ball Shocks America: Sexuality and Race in True Blood 53 Conclusion: All the Kids Are Doing It: Critiques of Patriarchal America in Teenaged Vampires 69 Works Cited 74 2 Introduction Vampires have been an enduring and powerful image throughout history, and each individual probably conjures up a different vampire in his or her head when hearing the word. -

The Metamorphosis, in the Penal Colony, and Other Stories Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE METAMORPHOSIS, IN THE PENAL COLONY, AND OTHER STORIES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Franz Kafka | 328 pages | 14 Nov 1995 | Schocken Books | 9780805210576 | English | New York, United States The Metamorphosis, In the Penal Colony, and Other Stories PDF Book If you want to know what happens next, go read the story, I'm not sure I could tell you anyway. It stuck with me for years but I never got around to reading anything else by Kafka until now. Kafka touches upon fundamental philosophical and political issues here. The suffering that many see A Hunger Artist A deep story that raises questions like 1. What if he were to say he was sick? I need to watch that. That the temporal shift to a happy future often does not have its own essence - perhaps we have ceased to exist until then. Get A Copy. But Kafka goes on to point out that perhaps beauty, or one of the great qualities of existence is its own discontinuous, within the continuous death-life. Their decisions and actions are heartbreaking, but logical. To this doorkeeper there comes a man from the country and prays for admittance to the Law. The lack of dialogue practically increases the family tragedy practically irreversible. Had Brod complied, it is possible, but I think doubtful, that we might not have heard of Kafka at all, that his status — in English anyway — might be closer to that of, say, Robert Walser, whom, by the way, Kafka admired. Sort order. The finale comes as follows: "Now he has not very long to live. -

"The Performance of Perversion in Kafka's Literature and Its Adaptations" Complete Thesis

THE PERFORMANCE OF PERVERSION IN KAFKA’S LITERATURE AND ITS ADAPTATIONS Davide Cerfeda Supervisors: Heather Benbow and Mark Nicholls Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER ONE ........................................................................................................................................... 5 OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 5 METHODOLOGY.................................................................................................................................... 5 WHAT ARE PERVERSIONS? ................................................................................................................... 7 THE WORLD THEATRE: PERFORMANCE AND PERFORMATIVITY ........................................................ 10 KAFKA’S LIFE: THE ORIGIN OF PERVERSION ....................................................................................... 12 THE PERVERSION OF GENDER ............................................................................................................ 15 NON-HUMAN ANIMALS: THE PERVERSION OF HUMANITY ............................................................... 18 A PERVERTED JUSTICE: LAW IN KAFKA’S