Case 4 Homegrocer.Com: Anatomy of a Failure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

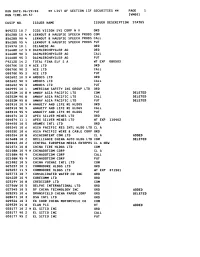

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 -

Online Grocery: How the Internet Is Changing the Grocery Industry

Graduate School of Business Administration UVA-DRAFT University of Virginia ONLINE GROCERY: HOW THE INTERNET IS CHANGING THE GROCERY INDUSTRY Online grocers ‘must create storefronts as easy to model appealing from an economic standpoint. They use as Amazon’s, build delivery infrastructure as argue that because they don’t need to pay for sound as UPS’ and pick and pack pickles and checkout clerks, display cases, or parking lots, online pineapples better than anyone ever has.’1 grocers can drop prices below those of retail stores and remain profitable.5 Key factors determining --Evie Black Dykema of Forrester Research success for the online grocery model include scalability, membership size, order frequency, and A survey by the University of Michigan order value. ranked 22 favorite household tasks, and found that grocery shopping came in next-to-last, just ahead of 2 Industry Projections and Outlook cleaning. According to the Food Marketing Institute (FMI), the average American household (HH) made Forrester Research segments the industry 2.3 trips to the grocery store a week and spent $87 3 into Full-service and Specialty online grocers (see per week on groceries. Andersen Consulting Figure 1). They predict that the full-service segment estimated that the average grocery trip took 47 will struggle to achieve the necessary economies of minutes, not including time to drive, park and unload 4 scale and to overcome hard-to-change consumer groceries. buying behaviors. Economic factors of the online grocery Full-service online grocers are located in model urban centers where critical volumes can be realized. Streamline.com estimates that the top twenty markets Proponents of the online grocery model point to numerous factors that they say makes the Figure 1: Projected electronic grocery spending of approximately $500 billion total industry (Source: Forrester Research) 1 David Henry, “Online grocers must change buyer habits, keep costs down,” USA Today, March 30, $12,000 2000, p. -

MARK S. THOMSON, on Behalf of Himself: No

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ___________________________________ MARK S. THOMSON, on behalf of himself: No. ___________________ and all others similarly situated, : : CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, : FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE : FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS v. : : MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER : & CO. and MARY MEEKER, : : Defendants. : JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ___________________________________ : Plaintiff, by his undersigned attorneys, individually and on behalf of the Class described below, upon actual knowledge with respect to the allegations related to plaintiff’s purchase of the common stock of Amazon.com, Inc. (“Amazon” or the “Company”), and upon information and belief with respect to the remaining allegations, based upon, inter alia, the investigation of plaintiff’s counsel, which included, among other things, a review of public statements made by defendants and their employees, Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) filings, and press releases and media reports, brings this Complaint (the “Complaint”) against defendants named herein, and alleges as follows: SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 1. In October 1999, Fortune named defendant Mary Meeker (“Meeker) the third most powerful woman in business, commenting, “[h]er brave bets – AOL in ‘93, Netscape in ‘95, e-commerce in ‘97, business to business in ‘99 – have earned her eight “ten-baggers”, stocks that have risen tenfold. Morgan Stanley’s “We’ve got Mary” pitch to clients has been key to its prominence in Internet financing. Her power is awesome: If she ever says “Hold Amazon.com”, Internet investors will lose billions.” 2. Fortune almost got it right. Investors did lose billions, but not because Meeker said “Hold Amazon.com”. Rather, investors were damaged by Meeker’s false and misleading statements encouraging investors to continue buying shares of Amazon. -

E-Commerce Is Changing the Face of Business, and Simon Students Will Be Well-Equipped to Meet the Challenges

WILLIAM E. SIMON GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE ADVISORY COMMITTEE Hiring Simon School Summer Associates… William E. Simon, WILLIAM E. SIMON GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION / WINTER 2000 Chairman …is the next best thing William Balderston III Harry Keefe to hiring our M.B.A.’s! Charles L. Bartlett Henry A. Kissinger O. T. Berkman Jr. William W. Lanigan, Esq. J. P. Bolduc Donald D. Lennox Paul A. Brands Jane Maas Andrew M. Carter Paul W. MacAvoy Richard G. Couch Louis L. Massaro Frank G. Creamer Jr. J. Richard Munro Ronald H. Fielding James Piereson Barry W. Florescue Robert E. Rich Jr. George J. Gillespie III, Esq. William D. Ryan James S. Gleason Leonard Schutzman Robert B. Goergen George J. Sella Jr. Paul S. Goldner Marilyn R. Seymann Bruce M. Greenwald J. Peter Simon Mark B. Grier William E. Simon Jr., Esq. Join the growing number of leading firms taking a General Alexander M. Haig Jr. Joel M. Stern closer look at what we’ve got to offer! Larry D. Horner Sir John M. Templeton Michael S. Joyce Ralph R. Whitney Jr. For more information, please call the Simon School Office of Career Services at 716-275-4881 David T. Kearns Joseph T. Willett William M. Kearns Jr. We are Committed to Your Success! UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER ROCHESTER, NEW YORK 14627 SWIIM L LION A M E. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Change Service Requested opportunity E-Commerce is changing the face of business, and Simon students will be well-equipped to meet the challenges. SPECIAL FEATURE: DEAN CHARLES PLOSSER’S ECONOMIC FORECAST FOR 2000 simonbusiness William E. -

Insights and Additions 3.1.1 Mobile B2C Shopping in Japan

Chapter Three: Retailing in Electronic Commerce: Products and Services 1 Online File W3.1 Some Current Trends in B2C EC Some important trends in B2C EC need to be noted at this point. First, many offline transactions are now heavily influ- enced by research conducted online, with approximately 85 percent of online shoppers now reporting that they used the Internet to research and influence their offline shopping choices (Jupitermedia.com 2006). Furthermore, it is estimated that by 2010, the Internet will influence approximately 50 percent of all retail sales, a significant increase over just 27 percent of all sales in 2005 (Jupitermedia.com 2006). Thus, multichannel retailers, those that have a physical presence and an online presence, seem destined to be the winners. They support the convenience of online research and sales, offer excellent order fulfillment and delivery if the sale is completed online, and enable customers to touch and feel and try on an item in a physical store. The need and opportunity to integrate offerings across all channels and to seek incentives for cross-channel sales is seen as an important development into the future (Mulpuru 2006). This becomes extremely impor- tant as the numbers of online shoppers reaches saturation, and successful e-tailers will be those who are able to increase the spending of existing buyers rather than purely focusing on attracting new buyers (Jupitermedia.com 2006). Another trend in B2C is the use of rich media in online advertising. For example, virtual reality is used in an online mall (Lepouras and Vassilakis 2006). Scene7.com is a leading vendor in the area. -

3Rd Quarter, 2000

RUN DATE:10/06/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:14:34 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4397 10 8 * APW LTD COM ADDED GO4397 90 8 APW LTD CALL ADDED GO4397 95 8 APW LTD PUT ADDED GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2108N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 9 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD WT EXP 071501 623773 10 7 CONSOLIDATED WATER CO INC ORD G2422R 10 9 * CORECOMM LTD ORD G2422R 90 9 CORECOMM LTD CALL G2422R 95 9 CORECOMM LTD PUT G2519Y 10 8 CREDICORP LTD COM G2706W 10 5 DELPHI INTERNATIONAL LTD ORD 627545 10 5 DF CHINA TECHNOLOGY INC ORD G2759W 10 1 DIGITAL UNITED HOLDINGS LTD ORD ADDED 628471 10 3 DSG INTL LTD ORD 629526 10 3 EK CHOR CHINA MOTORCYCLE CO COM 629539 14 8 ELAN PLC R T 630177 10 2 * EL SIT10 INC ORD 630177 90 2 EL SIT10 INC CALL RUN DATE:10/06/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 2 RUN TIME:14:34 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. -

Mutual Funds, and Real Estate

7700++ DDVVDD’’ss FFOORR SSAALLEE && EEXXCCHHAANNGGEE www.traders-software.com www.forex-warez.com www.trading-software-collection.com www.tradestation-download-free.com Contacts [email protected] [email protected] Skype: andreybbrv 10381_Sincere_fm.c 7/18/03 10:59 AM Page i UNDERSTANDING STOCKS Michael Sincere ebook_copyright 8 x 10.qxd 8/27/03 9:29 AM Page 1 Copyright © 2004 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a data- base or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-143582-4 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-140913-0 All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales pro- motions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. -

Competing in Book Retailing: the Case of Amazon.Com

UC Irvine I.T. in Business Title Competing in Book Retailing: The Case of Amazon.com Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/67p057vv Authors Shrikhande, Aarti Gurbaxani, Viijay Publication Date 1999-11-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMPETINGCOMPETING ININ CENTER FOR RESEARCH BOOK RETAILING: ON INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND THE CASE OF AMAZON.COM ORGANIZATIONS University of California, Irvine AUTHORS: 3200 Berkeley Place Aarti Shrikhande and Irvine, California 92697-4650 Vijay Gurbaxani and Graduate School of Management NOVEMBER 1999 Acknowledgement: This research has been supported by grants from the CISE/IIS/CSS Division of the U.S. National Science Foundation and the NSF Industry/University Cooperative Research Center (CISE/EEC) to the Center for Research on Information Technology and Organizations (CRITO) at the University of California, Irvine. Industry sponsors include: ATL Products, the Boeing Company, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Canon Information Systems, IBM, Nortel Networks, Rockwell International, Microsoft, Seagate Technology, Sun Microsystems, and Systems Management Specialists (SMS). The authors would like to thank Asish Ramchandran for his assistance on this project. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................................................1 INDUSTRY ENVIRONMENT AND COMPETITION .......................................................................................................2 -

Strategies for Success in the E-Grocery Industry Tong Niu

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses Thesis/Dissertation Collections 2008 Strategies for success in the e-grocery industry Tong Niu Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Niu, Tong, "Strategies for success in the e-grocery industry" (2008). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Thesis/Dissertation Collections at RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Strategies for Success in the e-Grocery Industry Tong Niu Department of Hospitality and Service Management Rochester Institute of Technology 2 ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Department of Hospitality and Service Management Graduate Studies M.S. Service Management Statement Granting or Denying Permission to Reproduce Thesis/Graduate Project The Author of a thesis or project should complete one of the following statements and include this statement as the page following the title page. Title of Thesis/project: Strategies for Success in the e-Grocery Industry I, Tong Niu , (grant, deny) permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of R.I.T. to reproduce the document titled above in whole or part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. OR I, , prefer to be contacted each time a request for reproduction is made. I can be reached at the following address: Date 11/18/2008 Signature 3 Acknowledgements The writing of this thesis has been an incredible learning process for me. Professor Bonalyn Nelsen’s invaluable experience and knowledge provided me with tremendous help and guided me through the completion of this thesis. -

Chapter 4: the (Non) Ubiquity of E-Tailing?

Chapter 4: The (Non) Ubiquity of E-tailing? During the Internet euphoria, no market seemed immune from having an “e” put in front of its name. Yet the retail markets that most lend themselves to Internet sales have the particular characteristics of a) high value relative to bulk and b) items that are not ‘experience’ goods, c) not instant gratification goods and d) not perishable goods. At the height of the Internet craze, received wisdom was that Internet retailing had advantages that were going to make brick-and-mortar firms relics, as if from some prehistoric age. “Creation of New Distribution Channels Create Opportunities for Retailers. The Internet represents the potential creation of the greatest, most efficient distribution vehicle in the history of the planet.” Mary Meeker, Morgan Stanley "Economies and interest rates can come and go, but every business over the next few year must aggressively become an e-business."…. Robert Austrian, Banc of America.35 Business Week: How will online selling change physical-world retailing? Bezos (Amazon Founder): The short answer is that strip malls go away because physical retailing is not going to be able to compete on price. That can't happen. If you study the economics, online retailing is just more efficient. Online stores are going to be the low-cost providers. As a result, that leaves other things for physical stores to compete on, and there are lots of dimensions that are important to customers besides price. One of them is entertainment…A second category of things is when you need something right now, this minute. -

Strategies and Challenges of Internet Grocery Retailing Logistics∗

Chapter 1 STRATEGIES AND CHALLENGES OF INTERNET GROCERY RETAILING LOGISTICS¤ Tom Hays United States Army Huntsville, Alabama [email protected] P³nar Keskinocak School of Industrial and Systems Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology Atlanta, Georgia [email protected] Virginia Malcome de L¶opez Pegasus Group Inc. San Juan, Puerto Rico [email protected] Abstract One of the most challenging sectors of the retail market today is the grocery segment, speci¯cally e-grocers. Since the mid-1990's multiple companies have entered the e-grocer market. Few have survived. What is it about e-grocers that make them fail? What makes them succeed? What can we learn from yesterday's e-grocers that will enable the new players to stay afloat or even be called \the greatest thing since sliced bread?" Given that the industry is still in \transition," it is di±cult to ¯nd de¯nite answers to these questions. With the goal of gaining useful insights on these issues, in this paper we analyze e-grocers, past ¤Forthcoming in Applications of Supply Chain Management and E-Commerce Research in Industry, J. Geunes, E. Ak»cal³,P.M. Pardalos, H.E. Romeijn, and Z.J. Shen (editors), Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004. 1 2 and present, discuss di®erent business models employed, as well as order ful¯llment and delivery strategies. Among the three alternative busi- ness models, namely, pure-play online, brick-and-mortar going online, and partnership between brick-and-mortar and pure-play online, we ob- serve that the latter model has a higher success potential by combining the strengths and minimizing the weaknesses of the former two models. -

Business Plan

myCFO Business Plan January 5, 2000 STARS0031068 Proprietary & Confidential I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY myCFOis a unique professional financial services firm focused on providing comprehensive,tailored financial solutions for individuals in varying stages of wealth accumulation. While myCFO’scurrent focus is dedicated to the $5 million and above high net worth (HNW)market in the United States, the companywill also extend its services in the near term serve other markets both internationally and in the U.S. Primary Market: U.S. high net worth households with $5 million and above HNhouseholds with $5 million or more in net worth spend an average of $145,000 per year per household on financial services, and comprise the most demandingand financially complexmarket for myCFO.Typically, these households use a variety of advisors for tax planning, investment planning, and wealth management.Additionally, these households also employpersonal staffs, whichmight include bookkeepers,drivers, nannies or pilots, all of whom need to be managed.As a result, HNWindividuals face a complicated, time intensive integration process to managetheir total financial situation, and ultimately are liable if anything goes wrong. myCFOcurrently provides an unsurpassed service offering to this segment by combining personalized financial counseling with state-of-the-art, Internet technology(the Online Service Offering). Each client has a single point of contact with a Client Service Director whoprovides a core offering of tax services, including individual tax consulting, tax planning, complianceand accountingservices. In addition, the Client Service Director provides a single point of contact for a full suite of specialty services, whichare providedthrough Specialty Directors with in- depth knowledgeon specific areas.