MARK S. THOMSON, on Behalf of Himself: No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On-Premise Vs. Cloud

WHITEPAPER Content Management for Mobile Devices: Smartphones, Use Cases and Best Practices in a Mobile-Centric World JULY 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Mobile-Delivered Content Is Growing Globally 3 Start with Smartphones 4 Challenges and Opportunities 5 Use Cases Drive Mobile Content Strategy 6 Overcoming Barriers To Implementation 7 Best Practices: Build For Success 8 Conclusions 9 About CrownPeak 10 2 Executive Summary In an environment where mobile web traffic tripled last year and mobile data users are expected to outpace desktop users by next year, the need for mobile-optimized content management is clear. Yet implementing content management systems has traditionally been a slow and resource-intensive process. One emerging strategy for successfully deploying mobile content is to focus on optimizing for smartphones, which offer both the largest and most stable mobile development platform. This approach has already proven successful in a number of market sectors and offers the advantages of simplicity, flexibility, and cost-effectiveness. A second strategy has been to leverage the new generation of Web Content Management systems. These systems combine breakthroughs in productivity with the ability to natively optimize content for mobile delivery, they work seamlessly with legacy systems, and typically do not require IT resources. The result is a significantly lower implementation and operation costs when compared to traditional content management solutions. Web Content Management (WCM) systems have traditionally been both time- and cost-intensive, requiring significant resources from expert developers and in- house IT. This paper recommends adoption of such a smartphone-centric strategy with a next-generation WCM to create a flexible, scalable, interoperable mobile content management solution, without impacting legacy systems or compromising data integrity. -

Internet Economy 25 Years After .Com

THE INTERNET ECONOMY 25 YEARS AFTER .COM TRANSFORMING COMMERCE & LIFE March 2010 25Robert D. Atkinson, Stephen J. Ezell, Scott M. Andes, Daniel D. Castro, and Richard Bennett THE INTERNET ECONOMY 25 YEARS AFTER .COM TRANSFORMING COMMERCE & LIFE March 2010 Robert D. Atkinson, Stephen J. Ezell, Scott M. Andes, Daniel D. Castro, and Richard Bennett The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation I Ac KNOW L EDGEMEN T S The authors would like to thank the following individuals for providing input to the report: Monique Martineau, Lisa Mendelow, and Stephen Norton. Any errors or omissions are the authors’ alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Dr. Robert D. Atkinson is President of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Stephen J. Ezell is a Senior Analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Scott M. Andes is a Research Analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Daniel D. Castro is a Senior Analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. Richard Bennett is a Research Fellow at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation. ABOUT THE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION FOUNDATION The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is a Washington, DC-based think tank at the cutting edge of designing innovation policies and exploring how advances in technology will create new economic opportunities to improve the quality of life. Non-profit, and non-partisan, we offer pragmatic ideas that break free of economic philosophies born in eras long before the first punch card computer and well before the rise of modern China and pervasive globalization. ITIF, founded in 2006, is dedicated to conceiving and promoting the new ways of thinking about technology-driven productivity, competitiveness, and globalization that the 21st century demands. -

Self-Funding for the Securities and Exchange Commission

Nova Law Review Volume 28, Issue 2 2004 Article 3 Self-Funding for the Securities and Exchange Commission Joel Seligman∗ ∗ Copyright c 2004 by the authors. Nova Law Review is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/nlr Seligman: Self-Funding for the Securities and Exchange Commission SELF-FUNDING FOR THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION JOEL SELIGMAN* I. THE INDEPENDENT REGULATORY AGENCIES GENERALLY ........... 234 II. A CASE STUDY: THE SEC ............................................................. 236 III. REVISITING THE INDEPENDENT REGULATORY AGENCY ............... 250 IV . SELF-FUN DIN G ............................................................................... 253 V . C O NCLUSIO N ..................................................................................259 What is the most important issue in effective securities regulation that was not addressed by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002? In my opinion, it is the issue of self-funding for the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC" or "Commission"). The experience of the SEC in the years immedi- ately preceding the Sarbanes-Oxley Act was one of an agency substantially underfinanced by Congress with a staff inadequate to fully perform such core functions as review of required filings. This dysfunction was the result of the inability of the Commission to ef- fectively secure appropriations to match its staff needs for the regulatory problems it was established to address. From the perspective of the White House and Congress, the SEC was just another agency. Its staff and budget requirements were consolidated with those of other agencies, and its rate of budgetary and staff adjustments were similar in significant aspects to the Executive Branch as a whole. Congress did not have the ability to focus on the precise regulatory dynamics of an agency like the SEC, to distinguish its needs from those of other agencies, and to address them in a timely fashion. -

Understanding Enron: "It's About Gatekeepers, Stupid"

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2002 Understanding Enron: "It's about Gatekeepers, Stupid" John C. Coffee Jr. Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons, Business Organizations Law Commons, and the Law and Economics Commons Recommended Citation John C. Coffee Jr., Understanding Enron: "It's about Gatekeepers, Stupid", 57 BUS. LAW. 1403 (2002). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2117 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding Enron: "It's About the Gatekeepers, Stupid" By John C. Coffee, Jr* What do we know after Enron's implosion that we did not know before it? The conventional wisdom is that the Enron debacle reveals basic weaknesses in our contemporary system of corporate governance.' Perhaps, this is so, but where is the weakness located? Under what circumstances will critical systems fail? Major debacles of historical dimensions-and Enron is surely that-tend to produce an excess of explanations. In Enron's case, the firm's strange failure is becoming a virtual Rorschach test in which each commentator can see evidence confirming 2 what he or she already believed. Nonetheless, the problem with viewing Enron as an indication of any systematic governance failure is that its core facts are maddeningly unique. -

Global / China Internet Trends

Global / China Internet Trends Shantou University / Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business / Hong Kong University November 7, 2005 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Outline • Attributes of Winning Companies • Global Internet • China Internet • Your Questions 2 Attributes of Winning Companies 3 Attributes of Winning Companies… 1. Large market opportunities - it is better to have 10%, and rising, market share of a $1 billion market than 100% of a $100M market 2. Good technology/service that offers a significant value/service proposition to its customers 3. Simple, direct mission and strong culture 4. Missionary (not mercenary), passionate, maniacally-focused founder(s) 5. Technology magnets (never underestimate the power of great engineers) 6. Great management team / board of directors / committed partners 7. Ability to lead change and embrace chaos 8. Leading/sustainable market position with first-mover advantage 9. Brand leadership, leading reach and market share 10.Global presence 4 …Attributes of Winning Companies 11. Insane customer focus and rapidly growing customer base 12. Stickiness and customer loyalty 13. Extensible product line(s) with focus on constant improvement and regeneration 14. Clear, broad distribution plans 15. Opportunity to increase customer “touch points” 16. Strong business and milestone momentum 17. Annuity-like business with sustainable operating leverage assisted by barriers-to-entry 18. High gross margins 19. Path to improving operating margins 20. Low-cost infrastructure and development efforts 5 Global Internet 6 Internet Data Points: Global… Global N. America = 23% of Internet users in 2005; was 66% in 1995 S. Korea Broadband penetration of 70%+ - No. 1 in world China More Internet users < age of 30 than anywhere 7 …Internet Data Points: Communications… Broadband 179MM global subscribers (+45% Y/Y, CQ2); 57MM in Asia; 45MM in N. -

The Uber Board Deliberates: Is Good Governance Worth the Firing of an Entrepreneurial Founder? by BRUCE KOGUT *

ID#190414 CU242 PUBLISHED ON MAY 13, 2019 The Uber Board Deliberates: Is Good Governance Worth the Firing of an Entrepreneurial Founder? BY BRUCE KOGUT * Introduction Uber Technologies, the privately held ride-sharing service and logistics platform, suffered a series of PR crises during 2017 that culminated in the resignation of Travis Kalanick, cofounder and longtime CEO. Kalanick was an acclaimed entrepreneur, building Uber from its local San Francisco roots to a worldwide enterprise in eight years, but he was also a habitual rule- breaker. 1 In an effort to put the recent past behind the company, the directors of Uber scheduled a board meeting for October 3, 2017, to vote on critical proposals from new CEO Dara Khosrowshahi that were focused essentially on one question: How should Uber be governed now that Kalanick had stepped down as CEO? Under Kalanick, Uber had grown to an estimated $69 billion in value by 2017, though plagued by scandal. The firm was accused of price gouging, false advertising, illegal operations, IP theft, sexual harassment cover-ups, and more.2 As Uber’s legal and PR turmoil increased, Kalanick was forced to resign as CEO, while retaining his directorship position on the nine- member board. His June 2017 resignation was hoped to calm the uproar, but it instead increased investor uncertainty. Some of the firm’s venture capital shareholders (VCs) marked down their Uber holdings by 15% (Vanguard, Principal Financial), while others raised the valuation by 10% (BlackRock).3 To restore Uber’s reputation and stabilize investor confidence, the board in August 2017 unanimously elected Dara Khosrowshahi as Uber’s next CEO. -

Weekly Internet / Digital Media / Saas Sector Summary

Weekly Internet / Digital Media / SaaS Sector Summary Week of July 14th, 2014 Industry Stock Market Valuation Internet / Digital Media / SaaS Last 12 Months Last 3 Months 180 120 14.6% 160 11.9% 60.8% 10.4% 10.4% 110 7.9% 140 22.3% 7.7% 21.0% 6.6% 20.4% 5.9% 120 20.0% 5.1% 16.3% 100 13.9% 100 13.0% 10.8% 80 90 7/12/13 9/23/13 12/5/13 2/16/14 4/30/14 7/12/14 4/11/14 5/4/14 5/27/14 6/19/14 7/12/14 (1) (2) (3) (4) Search / Online Advertising Internet Commerce Internet Content Publishers (5) (6) (7) (8) NASDAQ Diversified Marketing Media Conglomerates Gaming SaaS Notes: 1) Search/Online Advertising Composite includes: BCOR, BLNX-GB, CNVR, CRTO, GOOG, FUEL, MCHX, MM, MRIN, MSFT, QNST, RLOC, RUBI, TRMR, TWTR, YHOO, YNDX, YUME. 2) Internet Commerce Composite includes: AMZN, AWAY, COUP, CPRT, DRIV, EBAY, EXPE, FLWS, LINTA, NFLX, NILE, OPEN, OSTK, PCLN, PRSS, SSTK, STMP, TZOO, VPRT, ZU. 3) Internet Content Composite includes: AOL, CRCM, DHX, DMD, EHTH, IACI, MOVE, MWW, RATE, RENN, RNWK, SCOR, SFLY, TRLA, TST, TTGT, UNTD, WBMD, WWWW, XOXO, Z. 4) Publishers Composite includes: GCI, MMB-FR, NWSA, NYT, PSON-GB, SSP, TRI, UBM-GB, WPO. 5) Diversified Marketing Composite includes: ACXM, EFX, EXPN-GB, HAV-FR, HHS, IPG, MDCA, NLSN, VCI, WPP-GB. 6) Media Conglomerates Composite includes: CBS, CMCSA, DIS, DISCA, LGF, SNE, TWX, VIA.B. 7) Gaming Composite includes: 2432-JP, 3632-JP, 3765-JP, 700-HK, ATVI, CYOU, EA, GA, GAME, GLUU, NTES, PWRD, UBI-FR, ZNGA. -

How to Catch a Unicorn

How to Catch a Unicorn An exploration of the universe of tech companies with high market capitalisation Author: Jean Paul Simon Editor: Marc Bogdanowicz 2016 EUR 27822 EN How to Catch a Unicorn An exploration of the universe of tech companies with high market capitalisation This publication is a Technical report by the Joint Research Centre, the European Commission’s in-house science service. It aims to provide evidence-based scientific support to the European policy-making process. The scientific output expressed does not imply a policy position of the European Commission. Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of this publication. JRC Science Hub https://ec.europa.eu/jrc JRC100719 EUR 27822 EN ISBN 978-92-79-57601-0 (PDF) ISSN 1831-9424 (online) doi:10.2791/893975 (online) © European Union, 2016 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. All images © European Union 2016 How to cite: Jean Paul Simon (2016) ‘How to catch a unicorn. An exploration of the universe of tech companies with high market capitalisation’. Institute for Prospective Technological Studies. JRC Technical Report. EUR 27822 EN. doi:10.2791/893975 Table of Contents Preface .............................................................................................................. 2 Abstract ............................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary .......................................................................................... -

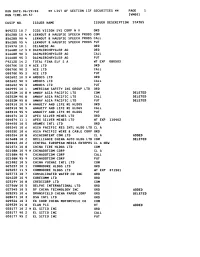

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 -

Where Are They Now? by Nicole Karp October 2012

Accounting Legends & Luminaries…Where Are They Now? by Nicole Karp October 2012 Lynn Turner was the SEC Chief Accountant from 1998 to 2001. During his controversial tenure, Turner strongly advocated for enhanced oversight rules, auditor independence, and higher quality financial reporting on a global basis. One of today’s main revenue recognition rules – SAB 101, which later became SAB 104 – was issued during his term. After leaving the SEC, Turner worked as a Professor of Accounting at Colorado State University. He then reentered the private sector, first as Managing Director of Research at Glass Lewis & Co. Today, Turner holds a Managing Director position at LitiNomics, a firm that provides research, Lynn Turner analyses, valuations and testimony in complex commercial litigations. Arthur Levitt was SEC Chairman from 1993 to 2001. During his term, Levitt gained a reputation as a champion for individual investors. He gave numerous speeches about corporate earning management, and was credited with calling attention to the wide use of “cookie jar reserves”. Levitt’s term ended shortly before the Enron scandal. Levitt’s reputation as Chairman isn’t without its blemishes, however. Levitt himself indicated that his opposition to a rule requiring companies to record stock option expense on the income statement was his biggest mistake as Chairman. Moreover, the SEC under Levitt's leadership failed to uncover Bernie Madoff's Ponzi scheme and approved the exemption of some Enron partnerships from the Investment Company Act of 1940. Arthur Levitt After leaving the SEC, Levitt continued to champion individual investors, authoring “Take on the Street: What Wall Street and Corporate America Don't Want You to Know”. -

Licensing the Word on the Street: the SEC's Role in Regulating Information

Buffalo Law Review Volume 55 Number 1 Article 2 5-1-2007 Licensing the Word on the Street: The SEC's Role in Regulating Information Onnig H. Dombalagian Tulane Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Onnig H. Dombalagian, Licensing the Word on the Street: The SEC's Role in Regulating Information, 55 Buff. L. Rev. 1 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol55/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO LAW REVIEW VOLUME 55 MAY 2007 NUMBER 1 Licensing the Word on the Street: The SEC's Role in Regulating Information ONNIG H. DOMBALAGIANt INTRODUCTION Information is said to be the lifeblood of financial markets.' Securities markets rely on corporate disclosures, quotes, prices, and indices, as well as the market structures, products, and standards that give them context and meaning, for the efficient allocation of capital in the global economy. The availability of and access to such information on reasonable terms has been identified as one t Associate Professor of Law, Tulane Law School. I would like to thank Roberta Karmel, Steve Williams, and Elizabeth King for their comments on prior drafts of this Article and Lloyd Bonfield, David Snyder, Jonathan Nash, and Christopher Cotropia for their helpful insights. -

Amazon.Com, Inc. Securities Litigation 01-CV-00358-Consolidated

Case 2:01-cv-00358-RSL Document 30 Filed 10/05/01 Page 1 of 215 1 THE HONORABLE ROBERT S. LASNIK 2 3 4 5 6 vi 7 øA1.S Al OUT 8 9 UNITE STAThS15iSTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON 10 AT SEATTLE 11 MAXiNE MARCUS, et al., On Behalf of Master File No. C-01-0358-L Themselves and All Others Similarly Situated, CLASS ACTION 12 Plaintiffs, CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT FOR 13 VS. VIOLATION OF THE SECURITIES 14 EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 AMAZON COM, INC., JEFFREY P. BEZOS, 15 WARREN C. JENSON, JOSEPH GALLI, JR., THOMAS A. ALBERG, L. JOHN DOERR, 16 MARK J BRITTO, JOEL R. SPIEGEL, SCOTT D. COOK, JOY D. COVEY, 17 'RICHARD L. DALZELL, JOHN D. RISHER, KAVITARK R. SHRIRAM, PATRICIA Q. 18 STONESIFER, JIMMY WRIGHT, ICELYN J. BRANNON, MARY E. ENGSTROM, 19 KLEJNER PERKINS CAUF1ELD & BYERS, MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER, 20 CREDIT SUISSE FIRST BOSTON, MARY MEEKER, JAMIE KIGGEN and USE BUYER, 21 Defendants. 22 In re AMAZON.COM, INC. SECURITIES 23 LITIGATION 24 This Document Relates To: 25 ALL ACTIONS 26 11111111 II 1111111111 11111 III III liii 1111111111111 111111 Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Le955 600 West Broadway, Suite 18 0 111111 11111 11111 liii III III 11111 11111111 San Diego, CA 92191 CV 01-00358 #00000030 TeIephone 619/231-058 Fax: 619/2j.23 Case 2:01-cv-00358-RSL Document 30 Filed 10/05/01 Page 2 of 215 TA L TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 Page 3 4 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW I 5 JURISDICTION AND VENUE .............................36 6 THE PARTIES ...........................