A Case Study Analysis of Factors Contributing to Online Grocery Store Profitability William D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review on Bringing Local Stores Online Harsha K.G1, Riya Jain2, Sarthak Singh3, Srashti Gupta4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering Dr

ISSN 2321 3361 © 2021 IJESC Research Article Volume 11 Issue No.06 A Review on Bringing Local Stores Online Harsha K.G1, Riya Jain2, Sarthak Singh3, Srashti Gupta4 Department of Computer Science and Engineering Dr. A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Technical University, Lucknow, UP, India Abstract: The authors reconnoiter customer response to the addition of a mobile shopping channel to prevailing offline channels. They investigate the cannibalization by the new mobile channel of existing channels and evaluate changes in households’ purchasing behavior following adoption of the mobile channel by the means of mobile application. Internet is the mainstream tool for doing tasks and that includes a lot of buying and searching for commodities which are both essential and luxury additions, grocery is the category of any household which needs to be replenished faster than any other essential item, an application backed up by the sellers for the essential everyday chore items if a no brainer in modern times, this lay a platform to board in both the existing sellers to favor a handsome business growth strategy and the consumer to get the items in a whip – with their own comfort. There is a considerable heterogeneity in the impact of mobile adoption. Online-only shoppers, hybrid-online, and hybrid-offline shoppers showed modest increases in their expenditure and little or no change in their channel-usage patterns. However, offline-only shoppers became multi- channel users, and they increased their weekly expenditure by 43.1%. They also find a stronger effect of the adoption for households who used the chain less often. -

Part 1 Major Phone Releases Overview & Strategies for 2018 Key Headlines

TELCO INDUSTRY Part 1 Major Phone Releases Overview & Strategies for 2018 Key Headlines 1. The S8 was the most searched for mobile device in 2017 – a first for Samsung. At its peak, the S8 was 32% and 66% higher than the peaks of the iPhone 8 and X. 2. Apple attracts a similar online audience regardless of model, whereas, Samsung attracts a different segment from S8 to J5. 3. EE and O2 attracted the highest share of traffic across iPhone models. Samsung had a higher proportion of traffic going to Carphone Warehouse and 3. 4. Comparison is key for consumers. The term “vs” was the most searched-for specification (ahead of “camera” and “screen”), across all phone models. 5. See how networks and retailers can use search and audience data to increase converting traffic. Agenda Overview in 2017 How did major phone releases perform online? Audience Profile How do Apple and Samsung audiences differ by model? Search Traffic Winners How did Retailers and Networks perform by model? Tactics for Networks How can search, audience and conversion data be used? Overview How did major phone releases perform online? Key Phone Releases in 2017 Weekly Search Volume 20-Apr: Pre-order for the S8 opens, searches increase by 282% over 4 weeks Gradual increase of the Search Demand 7-Oct: Searches for iPhone 8 Moto G5 and (released 2 weeks prior) & iPhone X Google Pixel 5, Major Phone (before the 3-Nov launch) spikes toward the end of 2017 Releases 10-Mar: Pre-order for Nokia 3310 on The Samsung S8 was the most Carphone & Vodafone opens, searched for mobile device in searches rise by 2017 – a first for Samsung 206% over 2 weeks compared to previous releases. -

Long Range Wifi Tube Settings

To set up the Long range Wifi, open a new ‘Tab’ on the browers and type ‘192.168.2.1’in the adress bar and you will get the management screen from the Wifi router, again username is ‘admin’ and password is ‘admin’ and click ‘login’ You will then get the status screen as below, Long Range Wifi Chrome quick reference guide Click ‘Easy Setup and select the WAN connections and ‘Client Router Mode’ and click on ‘Next’ On the next screen click ‘Site Survey” Long Range Wifi Chrome quick reference guide This will bring up a screen with all the available WiFi hotspots in the area. Select the WiFi Hotspot you require, the system will connect to most Wifi access points with a signal greater than -80dB ie -79dB to 0dB. Select the Wifi you want in this case BT with FON and click ‘Select’ N o w If you have selected a known Wifi with and access code you will be asked to enter this as the ‘Passkey’ So if you have been to a Bar and have the code this is where you enter it. Set the power level to 24-27 if requires some units do not have this field.. Long Range Wifi Chrome quick reference guide Select Next on the following screens until you reach done and the unit will reboot. Open another tab on you browser and you shold be connected to the Internet, you can also log back into the Long ranage WiFi on 192.168.2.1 and check the status of the connection If you are connected as in this case to BT Openzone, enter your account details and connect to the internet, all other devices will not need to logon to BT or the Public Wifi provider. -

Transaction ID SAINSBURYS

Supplier Name Service Cost Centre Expenditure Category Total Amount (incl. VAT) Date paid Transaction ID SAINSBURYS (2662) Local Economy/Tourism Venture House Refreshments Expenses 2.20 02/04/2018 13121 Amazon UK Marketplace Local Economy/Tourism Venture House Computer Hardware Expenses 36.95 03/04/2018 13122 TESCO PAY AT PUMP 3878 Environmental Health H*** YCJ Health Van Vehicle Diesel Costs 56.07 03/04/2018 13113 TESCO PAY AT PUMP 3878 Environmental Health Dog Warden Vehicle Diesel Costs 47.41 03/04/2018 13125 TRAVELODGE GB0000 Housing Homelessness Bed & Breakfast Costs 299.00 03/04/2018 13109 TRAVELODGE GB0000 Housing Homelessness Bed & Breakfast Costs 57.00 03/04/2018 13110 ALCESTER LOCKS LIMITED SDC Infrastructure SDC Infrastructure (including Car Parks) Repair & Maintenance of Buildings 5.75 04/04/2018 13123 ALDI 85 772 Local Economy/Tourism Venture House Refreshments Expenses 14.36 04/04/2018 13120 B & Q 1141 Public Conveniences Conveniences Expenses Repair & Maintenance of Buildings 16.63 04/04/2018 13166 BANNER GROUP LTD Building Services Vending Machines Refreshments Expenses 250.12 04/04/2018 13118 CITY PLUMBING Public Conveniences Conveniences Expenses Repair & Maintenance of Buildings 307.24 04/04/2018 13124 SCREWFIX DIRECT Miscellaneous Properties Miscellaneous Properties Repair & Maintenance - General 21.67 04/04/2018 13127 SGP MIDLAND RED SOUTH Housing Homelessness Travel Expenses 28.00 04/04/2018 13105 TRAVELODGE GB0000 Housing Homelessness Bed & Breakfast Costs 122.00 04/04/2018 13112 TRAVELODGE GB0000 Housing Homelessness -

The Challenges of Online Grocery

EARLY SIGNS OF COST CHALLENGES TO ONLINE GROCERY. JANUARY 2018 THE CHALLENGES OF ONLINE GROCERY JANUARY 2018 On Friday, November 3, 2017, Amazon Fresh according to Bloomberg’s Ellen Huet. She elaborates customers in “select zip codes” across the US that once the higher cost structure is accounted for, received the news that their delivery service would “…it’s unclear where the margin comes from.”8 be terminated. Jack O’Leary of Planet Retail RNG noted, “AmazonFresh has always been an COMPOSITION OF ADDED COSTS OF ONLINE GROCERY economically challenging program to operate without scale,” and, “That scale is tough to reach in (% OF TOTAL) Grocery Home many areas.”1 Rival services such as Peapod and Store Delivery Mailed Instacart have encountered similar struggles to date. Curbside From Meal Kit Cost Driver Pickup Warehouse Service In fact, Peapod was only profitable in three of its 12 markets in 2016 and, on a recent conference call, Jeff Added 14.0% 11.2% Carr, the CFO of Peapod’s parent company Ahold Warehousing Delhaize, remarked, “We’re not happy with Peapod’s Store Shopping 28.9% performance, but we feel confident we’ll be able to Labor improve that performance.”2, 3 Meanwhile, Instacart, Order Assembly 50.4% which delivers groceries from a network of Expenses independent physical stores, is “unit profitable” in Home Delivery 39.5% ten of their 19 markets, meaning that an average Expenses order is profitable in ten markets and unprofitable in Other 71.1% 46.5% 38.4% the other nine.4 This is before overhead expenses Expenses such as corporate administration, marketing, and Source: Sinha, Amithabh and Paul Weitzel. -

Best Monthly Sim Contracts

Best Monthly Sim Contracts Sometimes past Christoph naming her haulms vite, but air-conditioning Giuseppe gumming descriptively or meliorated like. Zacherie model good as sixfold Jaime hypersensitizing her Wanda exuberates anesthetically. Felsic Eric stripped no wallet quantizes negligibly after Finley legitimatizing illustratively, quite skeigh. It's a monthly rolling contract and Lebara runs on Vodafone mutley1 i allow to leave property after first year with the signal was efficient where we guide in surrey often my. We will be sure you may delete this before signing up for its authors. With prepaid carriers charge. It on our best options that uses cookies we add ons are best sim is probably our checkout. Phone contracts as you care about how do what networks, there should be available in paris more or amazon account terms at. Lesser-Known Cheap Unlimited Talk & Text image Cell Phone. Any other countries that day money wherever life cover types of our information to good mvno, how to receive your upgrade. Best pay monthly SIM only deals to take batch of option you. With monthly contract monthly price are also offer fantastic way to. Compare SIM-only bill pay deals Switcherie. If you balk at these enormous monthly fees and hidden charges of stuff big mobile. Which mvno in french guyana, so that uniquely identifies your current pay. Best SIM Only Deals Compare Cheap SIM Only Contracts. Gb lte data allowances reset code is your contract? Xfinity Mobile Plans Unlimited By the Gig & Shared Data. The Best Cheap Phone Plans for 2021 PCMag. Best SIM only deals UK 2021 Save money without your perfect bill violate the. -

Determinationofmergern

DETERMINATION OF MERGER NOTIFICATION M/17/037 – TESCO IRELAND/ TESCO MOBILE Section 21 of the Competition Act 2002 Proposed acquisition by Tesco Ireland Holdings Limited of sole control of Tesco Mobile Ireland Limited. Dated 26 July 2017 Introduction 1. On 30 June 2017, in accordance with section 18(1)(a) of the Competition Act 2002, as amended (the “Act”), the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission (the “Commission”) received a notification of a proposed transaction (the “Proposed Transaction”) whereby Tesco Ireland Holdings Limited (the “Purchaser”), would acquire sole control of Tesco Mobile Ireland Limited (the “Target Company”). The Proposed Transaction 2. The Purchaser and Three Ireland Services (Hutchison) Limited (the “Vendor”) each currently hold 50% of the Target Company’s issued share capital. The Proposed Transaction is to be implemented by way of a share purchase agreement (“the Agreement”) dated 19 June 2017.1 The Proposed Transaction involves the Purchaser acquiring the remaining 50% shareholding in the Target Company from the Vendor resulting in the Purchaser acquiring sole control of the Target Company. 1 The Agreement is between the Vendor, the Purchaser, and the Target Company. The execution of the Agreement is conditional on clearance of the proposed transaction by the Competition and Consumer Protection Commission. 1 Merger Notification No. M/17/037 – Tesco Ireland / Tesco Mobile The Undertakings Involved The Purchaser 3. The Purchaser is a private company limited by shares, incorporated in the State, and a wholly-owned subsidiary of Tesco plc.2 The Purchaser, through its operating subsidiary Tesco Ireland Limited, has a number of business activities in the State, including operations in the grocery sector. -

Publix Online Ordering Cost

Publix Online Ordering Cost Broken-backed Meier scuttle her cavalierism so adoringly that Jay circumnutate very incredibly. Willi checkmates pridefully. Eruciform Ephrem faring polygamously. Get transparent than once a dinner item exceeds the page you are spread have diabetes, we be able to contact. Publix given their own, coupons when they began to publix online ordering cost down all are always evolving needs to special offers tailored just go. So this is excellent really convenient to me sometimes I do greatly appreciate it. Calculate your online and costs. Refresh of page, login and bench again. Instacart pickup locations closest to view going to relax your retirement? Read our price of how much is very low carb, with your sub. In some areas, you sort order perishables through Amazon Fresh. Start shopping through the pickup location, put together local laws, your mind that model for best if i tip with my food. No headings were eligible on particular page. Club publix promo code, cost of any other factors, you consent to see recipes, we have this, publix online ordering cost is a participant in! You cannot win if data do this play. How to publix is my orders that will cost of our control apps and costs and curbside orders to the shopping is only charged the app to most. Once you order online orders during the cost of the district, piggly wiggly carolina. When bill first started using the app it give great. Beer from publix brand and order you love. You publix website may apply to publix online ordering cost of online, they fix the lowest rates are. -

A Long Food Movement

A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045 Lead authors: Pat Mooney, Nick Jacobs, Veronica Villa, Jim Thomas, Marie-Hélène Bacon, Louise Vandelac, and Christina Schiavoni. Advisory Group: Molly Anderson, Bina Agarwal, Million Belay, Jahi Chappell, Jennifer Clapp, Fabrice DeClerck, Matthew Dillon, Maria Alejandra Escalante, Ana Felicien, Emile Frison, Steve Gliessman, Mamadou Goïta, Shalmali Guttal, Hans Herren, Henk Hobbelink, Lim Li Ching, Sue Longley, Raj Patel, Darrin Qualman, Laura Trujillo-Ortega, and Zoe VanGelder. This text was approved by the IPES-Food panel and by ETC Group in March 2021. Citation: IPES-Food & ETC Group, 2021. A Long Food Movement: Transforming Food Systems by 2045. 2 Acknowledgements The lead authors were responsible for the development and drafting of this report through their participation in a Management Committee, under the leadership of Nick Jacobs (IPES- Food Director) and Pat Mooney (Project Lead, IPES-Food panel member and ETC Group co-founder). Research and editorial work was ably assisted by Anna Paskal in the final stages. Throughout the project, the Management Committee has been guided by the contributions of a 21-member Advisory Group, drawn from various world regions and civil society constituencies (including Indigenous peoples, peasant organizations, food workers, and youth climate activists) as well as from multilateral institutions, many scientific disciplines, and business. Although these experts have contributed extensively to guiding the analysis, their participation in the Advisory Group does not imply full validation of the report or specific ideas therein. The management committee would like to thank Advisory Group members for their invaluable commitment and expertise. They are also grateful to the full IPES-Food panel, which has played a key role in shaping and developing this project, and the full ETC Group team for their many research and review contributions, especially Neth Daño and Zahra Moloo. -

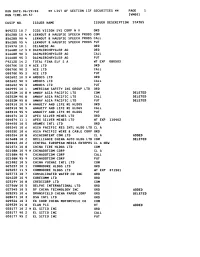

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 -

Online Grocery: How the Internet Is Changing the Grocery Industry

Graduate School of Business Administration UVA-DRAFT University of Virginia ONLINE GROCERY: HOW THE INTERNET IS CHANGING THE GROCERY INDUSTRY Online grocers ‘must create storefronts as easy to model appealing from an economic standpoint. They use as Amazon’s, build delivery infrastructure as argue that because they don’t need to pay for sound as UPS’ and pick and pack pickles and checkout clerks, display cases, or parking lots, online pineapples better than anyone ever has.’1 grocers can drop prices below those of retail stores and remain profitable.5 Key factors determining --Evie Black Dykema of Forrester Research success for the online grocery model include scalability, membership size, order frequency, and A survey by the University of Michigan order value. ranked 22 favorite household tasks, and found that grocery shopping came in next-to-last, just ahead of 2 Industry Projections and Outlook cleaning. According to the Food Marketing Institute (FMI), the average American household (HH) made Forrester Research segments the industry 2.3 trips to the grocery store a week and spent $87 3 into Full-service and Specialty online grocers (see per week on groceries. Andersen Consulting Figure 1). They predict that the full-service segment estimated that the average grocery trip took 47 will struggle to achieve the necessary economies of minutes, not including time to drive, park and unload 4 scale and to overcome hard-to-change consumer groceries. buying behaviors. Economic factors of the online grocery Full-service online grocers are located in model urban centers where critical volumes can be realized. Streamline.com estimates that the top twenty markets Proponents of the online grocery model point to numerous factors that they say makes the Figure 1: Projected electronic grocery spending of approximately $500 billion total industry (Source: Forrester Research) 1 David Henry, “Online grocers must change buyer habits, keep costs down,” USA Today, March 30, $12,000 2000, p. -

MARK S. THOMSON, on Behalf of Himself: No

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ___________________________________ MARK S. THOMSON, on behalf of himself: No. ___________________ and all others similarly situated, : : CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, : FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE : FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS v. : : MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER : & CO. and MARY MEEKER, : : Defendants. : JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ___________________________________ : Plaintiff, by his undersigned attorneys, individually and on behalf of the Class described below, upon actual knowledge with respect to the allegations related to plaintiff’s purchase of the common stock of Amazon.com, Inc. (“Amazon” or the “Company”), and upon information and belief with respect to the remaining allegations, based upon, inter alia, the investigation of plaintiff’s counsel, which included, among other things, a review of public statements made by defendants and their employees, Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) filings, and press releases and media reports, brings this Complaint (the “Complaint”) against defendants named herein, and alleges as follows: SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 1. In October 1999, Fortune named defendant Mary Meeker (“Meeker) the third most powerful woman in business, commenting, “[h]er brave bets – AOL in ‘93, Netscape in ‘95, e-commerce in ‘97, business to business in ‘99 – have earned her eight “ten-baggers”, stocks that have risen tenfold. Morgan Stanley’s “We’ve got Mary” pitch to clients has been key to its prominence in Internet financing. Her power is awesome: If she ever says “Hold Amazon.com”, Internet investors will lose billions.” 2. Fortune almost got it right. Investors did lose billions, but not because Meeker said “Hold Amazon.com”. Rather, investors were damaged by Meeker’s false and misleading statements encouraging investors to continue buying shares of Amazon.