A Tangled Webvan from the REGULAR and SPECIAL EDITIONS Special Report: 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Last Mile Delivery

Investors have risked billions on Webvan, Urbanfetch, and other same-day transporters. The economics, though, show they won’t deliver for long. Photographs Photographs by Brad Wilson The content business business models LastMile to 40 Nowhere Flaws & Fallacies in Internet Home-Delivery Schemes by Tim Laseter, Pat Houston, Anne Chung, Silas Byrne, Martha Turner, and Anand Devendran Tim Laseter Pat Houston Silas Byrne Anand Devendran ([email protected]) is ([email protected]), a prin- ([email protected]) is an ([email protected]) is a partner in Booz-Allen & cipal in Booz-Allen & Hamilton’s associate in Booz-Allen & a consultant in Booz-Allen & Hamilton’s Operations Practice Cleveland office and a member Hamilton’s New York office Hamilton’s New York office and serves on the firm’s of the Consumer and Health focusing on operational and focusing on operational and e-business core team. He is Group, focuses on strategic organizational issues across a growth strategies across a wide the author of Balanced Sourcing: supply-chain transformation, broad range of industries. range of industries. Cooperation and Competition in particularly as related to Supplier Relationships (Jossey- e-business issues. Martha Turner Bass, 1998). ([email protected]) is an Anne Chung associate in Booz-Allen & ([email protected]), a Hamilton’s New York office Cleveland-based principal of focusing on operations and Booz-Allen & Hamilton, focuses supply-chain management on e-business and supply-chain issues in a variety of industries, strategy as a member of the with particular emphasis on e- firm's Operations Practice. business. Amazon.com’s launch in July 1995 ushered in online sales potential; high cost of delivery; a selection– content an era with a fundamentally new value proposition to the variety trade-off; and existing, entrenched competition. -

KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON on Building Corporate Value

73009_FM 9/16/02 12:55 PM Page iii KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON On Building Corporate Value MUKUL PANDYA, HARBIR SINGH, ROBERT E. MITTELSTAEDT, JR., AND ERIC CLEMONS John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 73009_CH01I 9/13/02 11:45 AM Page 2 73009_FM 9/13/02 11:36 AM Page i KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON ON BUILDING CORPORATE VALUE 73009_FM 9/13/02 11:36 AM Page ii 73009_FM 9/16/02 12:55 PM Page iii KNOWLEDGE@WHARTON On Building Corporate Value MUKUL PANDYA, HARBIR SINGH, ROBERT E. MITTELSTAEDT, JR., AND ERIC CLEMONS John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 73009_FM 9/13/02 11:36 AM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Copyright © 2003 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400, fax 978-750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, 201-748-6011, fax 201-748-6008, e-mail: [email protected]. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. -

Walmart Inc. Takes on Amazon.Com

For the exclusive use of Q. Mays, 2020. 9-718-481 REV: JANUARY 21, 2020 DAVID COLLIS ANDY WU REMBRAND KONING HUAIYI CICI SUN Walmart Inc. Takes on Amazon.com At the start of 2018, Walmart faced critical decisions about its future as e-commerce continued to explode. Walmart just lost its long-held crown as the most valuable retailer in the world to online leader Amazon. With Amazon’s recent acquisition of Whole Foods for $13 billion, Amazon moved aggressively into the offline world to challenge Walmart in its biggest business, grocery. Walmart was not standing still, making moves like buying Jet.com for $3 billion in 2016. While Walmart’s U.S. e- commerce revenues grew to $11.5 billion in 2017, there was no debate in Bentonville, AR: Walmart remained far behind. The question for Walmart CEO Doug McMillon and Walmart.com head Marc Lore was how to respond to its most aggressive competitor ever (Exhibits 1a and 1b).1 Amazon The Early Years (1994–2001) Jeff Bezos founded Amazon in 1994 to exploit the Internet, still a relatively nascent technology. He determined that selling books online was most promising, because the number of titles available was greater than even the largest brick-and-mortar store could stock. Bezos and his wife drove west to start “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore” in Seattle, WA. Amazon offered 1 million titles for sale on its opening day in July 1995. Next year, the company had over 2.5 million book titles for sale, with revenue doubling every quarter (Exhibit 2). -

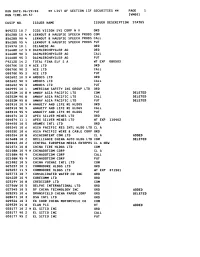

LIST of SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 Ivmool

RUN DATE:06/29/00 ** LIST OF SECTION 13F SECURITIES ** PAGE 1 RUN TIME:09:57 IVMOOl CUSIP NO. ISSUER NAME ISSUER DESCRIPTION STATUS B49233 10 7 ICOS VISION SYS CORP N V ORD B5628B 10 4 * LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS COM B5628B 90 4 LERNOUT & HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS CALL B5628B 95 4 LERNOUT 8 HAUSPIE SPEECH PRODS PUT D1497A 10 1 CELANESE AG ORD D1668R 12 3 * DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG ORD D1668R 90 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG CALL D1668R 95 3 DAIMLERCHRYSLER AG PUT F9212D 14 2 TOTAL FINA ELF S A WT EXP 080503 G0070K 10 3 * ACE LTD ORD G0070K 90 3 ACE LTD CALL G0070K 95 3 ACE LTD PUT GO2602 10 3 * AMDOCS LTD ORD GO2602 90 3 AMDOCS LTD CALL GO2602 95 3 AMDOCS LTD PUT GO2995 10 1 AMERICAN SAFETY INS GROUP LTD ORD G0352M 10 8 * AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD COM DELETED G0352M 90 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD CALL DELETED G0352M 95 8 AMWAY ASIA PACIFIC LTD PUT DELETED GO3910 10 9 * ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS ORD GO3910 90 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS CALL GO3910 95 9 ANNUITY AND LIFE RE HLDGS PUT GO4074 10 3 APEX SILVER MINES LTD ORD GO4074 11 1 APEX SILVER MINES LTD WT EXP 110402 GO4450 10 5 ARAMEX INTL LTD ORD GO5345 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC RES INTL HLDG LTD CL A G0535E 10 6 ASIA PACIFIC WIRE & CABLE CORP ORD GO5354 10 8 ASIACONTENT COM LTD CL A ADDED G1368B 10 2 BRILLIANCE CHINA AUTO HLDG LTD COM DELETED 620045 20 2 CENTRAL EUROPEAN MEDIA ENTRPRS CL A NEW G2107X 10 8 CHINA TIRE HLDGS LTD COM G2108N 10 9 * CHINADOTCOM CORP CL A G2108N 90 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP CALL G2lO8N 95 9 CHINADOTCOM CORP PUT 621082 10 5 CHINA YUCHAI INTL LTD COM 623257 10 1 COMMODORE HLDGS LTD ORD 623257 11 -

Online Grocery: How the Internet Is Changing the Grocery Industry

Graduate School of Business Administration UVA-DRAFT University of Virginia ONLINE GROCERY: HOW THE INTERNET IS CHANGING THE GROCERY INDUSTRY Online grocers ‘must create storefronts as easy to model appealing from an economic standpoint. They use as Amazon’s, build delivery infrastructure as argue that because they don’t need to pay for sound as UPS’ and pick and pack pickles and checkout clerks, display cases, or parking lots, online pineapples better than anyone ever has.’1 grocers can drop prices below those of retail stores and remain profitable.5 Key factors determining --Evie Black Dykema of Forrester Research success for the online grocery model include scalability, membership size, order frequency, and A survey by the University of Michigan order value. ranked 22 favorite household tasks, and found that grocery shopping came in next-to-last, just ahead of 2 Industry Projections and Outlook cleaning. According to the Food Marketing Institute (FMI), the average American household (HH) made Forrester Research segments the industry 2.3 trips to the grocery store a week and spent $87 3 into Full-service and Specialty online grocers (see per week on groceries. Andersen Consulting Figure 1). They predict that the full-service segment estimated that the average grocery trip took 47 will struggle to achieve the necessary economies of minutes, not including time to drive, park and unload 4 scale and to overcome hard-to-change consumer groceries. buying behaviors. Economic factors of the online grocery Full-service online grocers are located in model urban centers where critical volumes can be realized. Streamline.com estimates that the top twenty markets Proponents of the online grocery model point to numerous factors that they say makes the Figure 1: Projected electronic grocery spending of approximately $500 billion total industry (Source: Forrester Research) 1 David Henry, “Online grocers must change buyer habits, keep costs down,” USA Today, March 30, $12,000 2000, p. -

MARK S. THOMSON, on Behalf of Himself: No

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ___________________________________ MARK S. THOMSON, on behalf of himself: No. ___________________ and all others similarly situated, : : CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, : FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE : FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS v. : : MORGAN STANLEY DEAN WITTER : & CO. and MARY MEEKER, : : Defendants. : JURY TRIAL DEMANDED ___________________________________ : Plaintiff, by his undersigned attorneys, individually and on behalf of the Class described below, upon actual knowledge with respect to the allegations related to plaintiff’s purchase of the common stock of Amazon.com, Inc. (“Amazon” or the “Company”), and upon information and belief with respect to the remaining allegations, based upon, inter alia, the investigation of plaintiff’s counsel, which included, among other things, a review of public statements made by defendants and their employees, Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) filings, and press releases and media reports, brings this Complaint (the “Complaint”) against defendants named herein, and alleges as follows: SUMMARY OF THE ACTION 1. In October 1999, Fortune named defendant Mary Meeker (“Meeker) the third most powerful woman in business, commenting, “[h]er brave bets – AOL in ‘93, Netscape in ‘95, e-commerce in ‘97, business to business in ‘99 – have earned her eight “ten-baggers”, stocks that have risen tenfold. Morgan Stanley’s “We’ve got Mary” pitch to clients has been key to its prominence in Internet financing. Her power is awesome: If she ever says “Hold Amazon.com”, Internet investors will lose billions.” 2. Fortune almost got it right. Investors did lose billions, but not because Meeker said “Hold Amazon.com”. Rather, investors were damaged by Meeker’s false and misleading statements encouraging investors to continue buying shares of Amazon. -

The End of Bankruptcy

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2002 The ndE of Bankruptcy Robert K. Rasmussen Douglas G. Baird Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert K. Rasmussen & Douglas G. Baird, "The ndE of Bankruptcy" (John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics Working Paper No. 173, 2002). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO JOHN M. OLIN LAW & ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 173 (2D SERIES) The End of Bankruptcy Douglas G. Baird and Robert K. Rasmussen THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO This paper can be downloaded without charge at: The Chicago Working Paper Series Index: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=359241 The End of Bankruptcy Douglas G. Baird* & Robert K. Rasmussen** ABSTRACT The law of corporate reorganizations is conventionally justified as a way to preserve a firm’s going-concern value: Specialized assets in a particular firm are worth more together in that firm than anywhere else. This paper shows that this notion is mistaken. Its flaw is that it lacks a well- developed understanding of the nature of a firm. -

E-Commerce Is Changing the Face of Business, and Simon Students Will Be Well-Equipped to Meet the Challenges

WILLIAM E. SIMON GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION EXECUTIVE ADVISORY COMMITTEE Hiring Simon School Summer Associates… William E. Simon, WILLIAM E. SIMON GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION / WINTER 2000 Chairman …is the next best thing William Balderston III Harry Keefe to hiring our M.B.A.’s! Charles L. Bartlett Henry A. Kissinger O. T. Berkman Jr. William W. Lanigan, Esq. J. P. Bolduc Donald D. Lennox Paul A. Brands Jane Maas Andrew M. Carter Paul W. MacAvoy Richard G. Couch Louis L. Massaro Frank G. Creamer Jr. J. Richard Munro Ronald H. Fielding James Piereson Barry W. Florescue Robert E. Rich Jr. George J. Gillespie III, Esq. William D. Ryan James S. Gleason Leonard Schutzman Robert B. Goergen George J. Sella Jr. Paul S. Goldner Marilyn R. Seymann Bruce M. Greenwald J. Peter Simon Mark B. Grier William E. Simon Jr., Esq. Join the growing number of leading firms taking a General Alexander M. Haig Jr. Joel M. Stern closer look at what we’ve got to offer! Larry D. Horner Sir John M. Templeton Michael S. Joyce Ralph R. Whitney Jr. For more information, please call the Simon School Office of Career Services at 716-275-4881 David T. Kearns Joseph T. Willett William M. Kearns Jr. We are Committed to Your Success! UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER ROCHESTER, NEW YORK 14627 SWIIM L LION A M E. GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION Change Service Requested opportunity E-Commerce is changing the face of business, and Simon students will be well-equipped to meet the challenges. SPECIAL FEATURE: DEAN CHARLES PLOSSER’S ECONOMIC FORECAST FOR 2000 simonbusiness William E. -

Duke University 2002-2003

bulletin of Duke University 2002-2003 The Fuqua School of Business University’s Mission Statement James B. Duke’s founding Indenture of Duke University directed the members of the University to “provide real leadership in the educational world” by choosing indi- viduals of “outstanding character, ability and vision” to serve as its officers, trustees and faculty; by carefully selecting students of “character, determination and application;” and by pursuing those areas of teaching and scholarship that would “most help to de- velop our resources, increase our wisdom, and promote human happiness.” To these ends, the mission of Duke University is to provide a superior liberal educa- tion to undergraduate students, attending not only to their intellectual growth but also to their development as adults committed to high ethical standards and full participa- tion as leaders in their communities; to prepare future members of the learned profes- sions for lives of skilled and ethical service by providing excellent graduate and professional education; to advance the frontiers of knowledge and contribute boldly to the international community of scholarship; to promote an intellectual environment built on a commitment to free and open inquiry; to help those who suffer, cure disease and promote health, through sophisticated medical research and thoughtful patient care; to provide wide ranging educational opportunities, on and beyond our campuses, for traditional students, active professionals and life-long learners using the power of in- formation technologies; and to promote a deep appreciation for the range of human dif- ference and potential, a sense of the obligations and rewards of citizenship, and a commitment to learning, freedom and truth. -

THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE of CALIFORNIA the 151St Diocesan

THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF CALIFORNIA The 151st Diocesan Convention October 21, 2000 Grace Cathedral San Francisco, California DioCal 003958 AGENDA OF THE 151st DIOCESAN CONVENTION "CALL TO MISSION: THE JUBILEE YEARS" October 21,2000 Location 8:00-9:20am Registration: Tables are open 8:00-9:20 a.m. Cathedral Nave 9:00 Call to Order Gresham Hall Morning Prayer Secretary's Announcements Introduction of New Clergy, Interims; Necrology Report of Committee on Dispatch of Business Report of Committee on Nominations First Report of Resolutions Committee 9::40 Bishap's Address 10:20 Instruction on First Ballot Vote 1 st Ballot -Registration Tables Cathedral Nave 10:40 Discussion Groups —Episcopal Charities, General Convention, New Church Start-up, Theological Reflection Task Force for Technology and Interfaith Issues 11:45 Plenary Session with Bishop Swing Gresham Hall Noonday Prayer 12:30-1:30pm LUNCH PLAZA 1:30 Reconvene Gresham Hall Discussion and Action on the Bishop's Address Report on Resolutions (Tentative) 2:30 Department of Youth and Young Adult Presentation Report of the Diocesan Treasurer Report of 1st Ballot Vote 2nd Ballot -Registration Tables Cathedral Nave Report of the Committee on Persoruzel Practices Report of the Division of Program and Budget Action on the Proposed 2001 Operating Budget Report on 2nd Ballot Bishop's Appointments and Announcements 3:30 Adjourn DioCal 003959 The Bishop's Appointments to Convention Committees for the 151st Diocesan Convention Committee on Credentials: Nigel Renton, Secretary Mr. Dennis Delman, Ballots Mrs. Mary Louise Gotthold, Registrar The Rev. George Sotelo, Nominations Division of Program and Budget: Mr. Paul Evans, Chair The Rev. -

Top 10 Dot-Com Flops by Kent German the Most Astounding Thing About the Dot-Com Boom Was the Obscene Amount of Money Spent

Top 10 dot-com flops By Kent German The most astounding thing about the dot-com boom was the obscene amount of money spent. Zealous venture capitalists fell over themselves to invest millions in start-ups; dot-coms blew millions on spectacular marketing campaigns; new college graduates became instant millionaires and rushed out to spend it; and companies with unproven business models executed massive IPOs with sky-high stock prices. We all know what eventually happened. Most of hese start-ups died dramatic deaths. These are the celebrity victims of the new- economy bust. You can avoid giving a flop as a gift this holiday. Take a look at the CNET Holiday Gift Guide. Webvan (1999-2001) A core lesson from the dot-com boom is that even if you have a good idea, it's best not to grow too fast too soon. But online grocer Webvan was the poster child for doing just that, making the celebrated company our number one dot-com flop. In a mere 18 months, it raised $375 million in an IPO, expanded from the San Francisco Bay Area to eight U.S. cities, and built a gigantic infrastructure from the ground up (including a $1 billion order for a group of high-tech warehouses). Webvan came to be worth $1.2 billion (or $30 per share at its peak), and it touted a 26-city expansion plan. But considering that the grocery business has razor-thin margins to begin with, it was never able to attract enough customers to justify its spending spree. -

Insights and Additions 3.1.1 Mobile B2C Shopping in Japan

Chapter Three: Retailing in Electronic Commerce: Products and Services 1 Online File W3.1 Some Current Trends in B2C EC Some important trends in B2C EC need to be noted at this point. First, many offline transactions are now heavily influ- enced by research conducted online, with approximately 85 percent of online shoppers now reporting that they used the Internet to research and influence their offline shopping choices (Jupitermedia.com 2006). Furthermore, it is estimated that by 2010, the Internet will influence approximately 50 percent of all retail sales, a significant increase over just 27 percent of all sales in 2005 (Jupitermedia.com 2006). Thus, multichannel retailers, those that have a physical presence and an online presence, seem destined to be the winners. They support the convenience of online research and sales, offer excellent order fulfillment and delivery if the sale is completed online, and enable customers to touch and feel and try on an item in a physical store. The need and opportunity to integrate offerings across all channels and to seek incentives for cross-channel sales is seen as an important development into the future (Mulpuru 2006). This becomes extremely impor- tant as the numbers of online shoppers reaches saturation, and successful e-tailers will be those who are able to increase the spending of existing buyers rather than purely focusing on attracting new buyers (Jupitermedia.com 2006). Another trend in B2C is the use of rich media in online advertising. For example, virtual reality is used in an online mall (Lepouras and Vassilakis 2006). Scene7.com is a leading vendor in the area.