Evaluation of the CAP Measures Applicable to the Wine Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Bin 16 NV Laurent-Perrier, Brut, Chardonnay/Pinot Noir

Sparkling Wines Splits and Half bottles bin 11 N.V. Charles Roux, Blanc de Blanc, Brut Chardonnay/Aligote, France split 6 14 N.V. Villa Sandi Prosecco Glera, Prosecco DOC split 7.5 16 N.V. Laurent-Perrier, Brut, Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Pinot Meunier, Champagne split 16.5 17 N.V. Suzuki Shuzouten “La Chamte” Carbonated Sake, Akitakomachi (rice), Sweet, Akita 280ml 16 20 N.V. Adriano Adami “Garbèl” Brut Prosecco, Glera, Prosecco DOC half 19 22 N.V. Champagne Tribaut Schloesser à Romery, Brut Origine, Pinot Noir/Chardonnay/Pinot Meunier, Champagne split 21 23 N.V. Champagne Tribaut Schloesser à Romery, Brut Origine, Pinot Noir/Chardonnay/Pinot Meunier, Champagne half 30 27 N.V. Drappier Brut Rosé Pinot Noir, Champagne half 39 28 N.V. Pierre Gimonnet & Fils, Blanc de Blanc, Cuis 1er Cru, Chardonnay Brut, Champagne half 42 Full Bottles bin 105 N.V. Poema, Cava, Parellada/Macabeo/Xarel-lo, Penedès 23 107 N.V. Le Contesse Rosé of Pinot Noir, Brut, Italy 27 111 N.V. Varichon & Clerc Privilège Ugni Blanc/Chardonnay Chenin Blanc/Jacquère , Blanc de Blancs Savoie 29 113 N.V. Ruggeri “Argeo” Prosecco Brut Glera/Verdiso/Perera, Prosecco DOC 30 114 N.V. Faire la Fête Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Chenin Blanc, Crémant de Limoux 31 119 N.V. Domaine Fay d'Homme “X Bulles” Melon de Bourgogne, Vin de France 33 122 N.V. Sektkellerei Szigeti, Gruner Veltliner, Österreichischer Sekt, Austria 34 123 2013 Argyle Brut, Grower Series Pinot Noir/Chardonnay, Willamette Valley 36 125 N.V. Domaine Thévenet et Fils, Blanc de Blancs Chardonnay, Crémant de Borgogne 37 126 N.V. -

Signature Cocktails Classico Mocktails

signature cocktails Punt e Sol 90 Mrs Negroni 110 Punt e Mes vermouth, Aperol, Beefeater gin, Lillet Blanc, Aperol, crème brûlée syrup, lime juice, red currant mint, ginger beer Capitano Milla 110 Havana’O Fashioned 120 Chamomile infused Luxardo gin, Havana Club 7yrs, Xocolatl Mole Peychauds, Green Chartreuse, lemon bitter, orange bitter, coffee mist juice, vanilla syrup, eggwhite, rosemary Sparrow 95 Rosalina Secco 90 Amaro Montenegro, pineapple juice, Absolut vodka, Chambord, rose syrup, lemon juice, sugar syrup grapefruit juice, prosecco Classico Old Fashioned 90 Margarita 100 Ballantine’s, brown sugar, Olmeca Blanco, lime juice, Angostura bitter Cointreau, sugar syrup Negroni 110 Whiskey Sour 90 Beefeater, Campari, Ballantine’s, lemon juice, contratto bitter egg white, sugar Moscow Mule 100 Cosmopolitan 120 Absolut vodka, lime juice, Absolut vodka, Cointreau, Angostura bitter, ginger beer lime juice, cranberry juice mocktails 60 Basil Beauty Milano Iced Tea Passion fruit puree, lemon juice, Jasmine tea, lemon juice, lychee lime juice, coconut syrup, puree, lemongrass, vanilla syrup pineapple juice, basil Rosemary Blueberry Smash Blueberry, rosemary, agave, lemon juice, soda water No service charge. All tips go to our staff. 2 3 by the glass White Soligo Pinot Grigio DOC 2018 (Pinot Grigio, Veneto) 75 Blanc, Chardonnay Oltrepo Pavese DOC 2017 120 (Chardonnay, Lombardy) Suavia Soave Classico 2017 (Garganega, Veneto) 100 La Cantina Cellaro Luma 2017 (Grillo, Sicily) 90 Red Tedeschi Valpolicella Superiore 2016 70 (Corvina, Corvinone, -

Catalogo Prodotti Condizioni Generali

CATALOGO PRODOTTI CONDIZIONI GENERALI La Famiglia Gregoletto vanta una lunga tradizione nel mondo del vino, come possono testimoniare alcuni documenti che indicano come, già all’inizio del Seicento, questa coltivasse la vite sulle colline di Premaor di Miane. Ad accentuare il carattere storico c’è l’edificio che ospita la cantina, ricavato da una struttura seicentesca. L’attività enoica della famiglia ha avuto un notevole impulso soprattutto nel dopoguerra, grazie a Luigi Bene e fedelmente Gregoletto, che ha iniziato a produrre vino secondo criteri di qualità e tipicità. Oggi l’azienda possiede diciotto ettari di terreno vitato, allocati in media e alta collina, nei comuni di Miane, San Pietro di Feletto e Refrontolo. La vendemmia avviene manualmente in momenti diversi in modo da ottenere la maturazione ideale dei grappoli (vendemmia differenziata). L’uva viene pigiata in giornata e i mosti ottenuti vengono tenuti divisi per luogo di provenienza. Nella primavera successiva alla vendemmia il Prosecco viene imbottigliato in tre diverse versioni: il tranquillo, che i Gregoletto hanno sempre considerato la gemma di famiglia, lo spumante Extra Dry ed il frizzante. Il Prosecco frizzante viene prodotto con il metodo della fermentazione naturale in bottiglia “sur lie”. L’azienda produce, oltre al Prosecco e al Verdiso dei Colli Trevigiani IGT, il Merlot dei Colli Trevigiani IGT, il Cabernet del Colli Trevigiani IGT, il Colli di Conegliano DOC Bianco e Rosso, il Manzoni Bianco dei Colli Trevigiani IGT e la Grappa di Prosecco. Su appuntamento è possibile assaggiare i vini prodotti dall’azienda, visitando così la sala degustazione, la cantina e la fornita biblioteca di libri storici legati alla enologia e alla viticultura. -

Prosecco-Way Beyond Bubbles-Presented by Alan Tardi

Way Beyond Bubbles Terroir, Tradition and Technique in Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco Alan Tardi Modern History The modern history of Prosecco begins in 1876 when enologist Giovanni Battista Cerletti founded the Scuola Enologico in Conegliano (an outgrowth of the Enological Society of the Treviso Province created in 1868). Carpenè’s groundbreaking La Vite e il Vino nella Wine maker and enologist work, Provincia di Treviso (1874), lists Antonio Carpenè (1838- a staggering number of 1902) played a significant different (mostly indigenous) role in the creation and grape varieties being cultivated operation of the school. in the Province of Treviso as well as many different viticultural systems and trellising methods (including training vines up into trees). Over in Piedmont, in 1895 Federico Martinotti, director of the Experimental Station of Enology in Asti (founded in January, 1872 by Royal Decree of Victor Emanuele Il, King of Italy) developed and patented the technique of conducting the second fermentation in large pressurized temperature- controlled receptacles. The technology was immediately and developed by the Conegliano school. [In 1910, Eugène Charmat adopted an existing device called the autoclave (which was invented in 1879 by a colleague of Louis Pasteur named Charles Chamberland) for the production of sparkling wine. The name stuck...] • By around 1910 the autoclave technology was was perfected for use in the production of sparkling wines in the Conegliano Valdobbiadene area. At about the same time, phylloxera broke out, followed shortly thereafter by WW I and economic depression. • It was not until the economic resurgence of Italy following WW II in the mid-1950s and ‘60s that the autoclave became diffused throughout the area of Conegliano Valdobbiadene and the modern day wine industry was born. -

GI Journal No. 145 1 April 30, 2021

GI Journal No. 145 1 April 30, 2021 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GEOGRAPHICAL INDICATIONS JOURNAL NO. 145 APRIL 30, 2021 / VAISAKA 10, SAKA 1943 GI Journal No. 145 2 April 30, 2021 INDEX S. No. Particulars Page No. 1 Official Notices 4 2 New G.I Application Details 5 3 Public Notice 6 4 GI Applications 7 Conegliano Valdobbiadene Prosecco – GI Application No. 353 Franciacorta - GI Application No. 356 Chianti - GI Application No. 361 5 GI Authorised User Applications Kangra Tea – GI Application No. 25 Mysore Traditional Paintings – GI Application No. 32 Kashmir Pashmina – GI Application No. 46 Kashmir Sozani Craft – GI Application No. 48 Kani Shawl – GI Application No. 51 Alphonso – GI Application No. 139 Kashmir Walnut Wood Carving – GI Application No. 182 Thewa Art Work – GI Application No. 244 Vengurla Cashew – GI Application No. 489 Purulia Chau Mask – GI Application No. 565 Wooden Mask of Kushmandi – GI Application No. 566 Tirur Betel Leaf (Tirur Vettila) – GI Application No. 641 5 General Information 6 Registration Process GI Journal No. 145 3 April 30, 2021 OFFICIAL NOTICES Sub: Notice is given under Rule 41(1) of Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Rules, 2002. 1. As per the requirement of Rule 41(1) it is informed that the issue of Journal 145 of the Geographical Indications Journal dated 30th April, 2021 / Vaisaka 10, Saka 1943 has been made available to the public from 30th April, 2021. GI Journal No. 145 4 April 30, 2021 NEW G.I APPLICATION DETAILS App.No. Geographical Indications Class Goods 746 Goan Bebinca -

Bin 16 NV Laurent-Perrier, Brut, Chardonnay/Pinot Noir

Sparkling Wines Splits and Half bottles bin 11 N.V. Charles Roux, Blanc de Blancs, Brut Chardonnay/Aligote, France split 6 14 N.V. Villa Sandi Prosecco Glera, Prosecco DOC split 7.5 15 N.V. François Montand Brut Rosé of Grenache/Cinsault, France (Revermont) split 7.5 16 N.V. Laurent-Perrier, Brut, Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Pinot Meunier, Champagne split 16.5 17 N.V. Suzuki Shuzouten “La Chamte” Carbonated Sake, Akitakomachi (rice), Sweet, Akita 280ml 16 19 N.V. Faire la Fête Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Chenin Blanc, Crémant de Limoux half 16 20 N.V. Adriano Adami “Garbèl” Brut Prosecco, Glera, Prosecco DOC half 19 22 N.V. Champagne Tribaut Schloesser à Romery, Brut Origine, Pinot Noir/Chardonnay/Pinot Meunier, Champagne split 21 24 N.V. Champagne Jacquart, Brut Mosaïque, Chardonnay/Pinot Noir/Pinot Meunier, Champagne half 31 26 N.V. Champagne Canard-Duchêne, Brut, Pinot Noir/Pinot Meunier/Chardonnay, Champagne half 32 28 N.V. Pierre Gimonnet & Fils, Blanc de Blancs, Cuis 1er Cru, Chardonnay Brut, Champagne half 42 Full Bottles bin 105 N.V. Poema, Cava, Parellada/Macabeo/Xarel-lo, Penedès 23 107 N.V. Le Contesse Rosé of Pinot Noir, Brut, Italy 27 113 N.V. Ruggeri “Argeo” Prosecco Brut Glera/Verdiso/Perera, Prosecco DOC 30 119 N.V. Domaine Fay d'Homme “X Bulles” Melon de Bourgogne, Vin de France 33 121 N.V. Sektkellerei Szigeti, Gruner Veltliner, Österreichischer Sekt, Austria 34 122 N.V. Domaine de la Voûte des Crozes “Effervescence” Gamay, France 35 123 2013 Argyle Brut, Grower Series Pinot Noir/Chardonnay, Willamette Valley 36 125 N.V. -

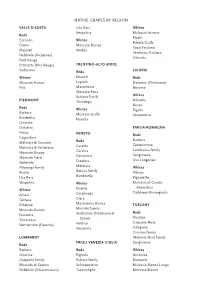

Native Grapes by Region

NATIVE GRAPES BY REGION VALLE D’AOSTA Uva Rara Whites Vespolina Malvasia Istriana Reds Picolit Cornalin Whites Ribolla Gialla Fumin Moscato Bianco Tocai Friulano Mayolet Verdea Verduzzo Friulano Nebbiolo (Picotener) Vitovska Petit Rouge Prëmetta (Prié Rouge) TRENTINO-ALTO ADIGE Vuillermin Reds LIGURIA Whites Enantio Reds Moscato Bianco Lagrein Dolcetto (Ormeasco) Prié Marzemino Rossese Moscato Rosa Schiava family Whites PIEDMONT Teroldego Albarola Bosco Reds Whites Pigato Barbera Moscato Giallo Vermentino Brachetto Nosiola Croatina Dolcetto EMILIA-ROMAGNA Freisa VENETO Reds Grignolino Barbera Malvasia di Casorzo Reds Centesimino Malvasia di Schierano Casetta Lambrusco family Moscato Bianco Corvina Sangiovese Moscato Nero Corvinone Uva Longanesi Nebbiolo Croatina Pelaverga family Molinara Whites Ruché Raboso family Albana Uva Rara Rondinella Pignoletto Vespolina Whites Malvasia di Candia Aromatica Whites Durella Trebbiano Romagnolo Arneis Garganega Cortese Glera Erbaluce Marzemina Bianca TUSCANY Moscato Bianco Moscato family Reds Nascetta Verdicchio (Trebbiano di Aleatico Timorasso Soave) Canaiolo Nero Vermentino (Favorita) Verdiso Vespaiola Ciliegiolo Colorino family LOMBARDY Malvasia Nera family FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA Sangiovese Reds Barbera Reds Whites Croatina Pignolo Ansonica Groppello family Refosco family Biancone Moscato di Scanzo Schioppettino Malvasia Bianca Lunga Nebbiolo (Chiavennasca) Tazzelenghe Moscato Bianco Trebbiano Toscano Whites BASILICATA Vernaccia di San Gimignano Montonico Bianco Reds Pecorino Aglianico UMBRIA Trebbiano -

Prosecco On-Premise Training Guide

Prosecco on-premise training guide Prosecco is among Italy's largest wine categories and is recognized and well-loved by consumers around the world. With sales growth rates outpacing Champagne, Prosecco is an important wine to understand and include in your beverage program. This guide offers an opportunity for you to dig deeper into the region and discover how the local terroir (i.e., all of the vineyard and cellar factors that shape how a wine tastes) and winemaking techniques make different styles of Prosecco. This knowledge will help you develop a dialogue with your guests to build trust and confidence. Prosecco is the ultimate in affordable luxury, but there is more to Prosecco than brunch bubbles! 1 How is Prosecco made? While it’s often compared to Champagne, Prosecco is made using a different process where the bubbles are created in a pressurized tank rather than an individual bottle (the latter is the production method used in Champagne). The process goes by several names including Tank Method or Charmat Method, but Italians refer to it as the Martinotti Method. Italian Federico Martinotti developed and patented this sparkling wine method in 1895, but that design was improved upon by Frenchman Eugène Charmat in 1907, and the Charmat name stuck. Are all Proseccos sparkling? The vast majority of Prosecco is spumante (fully sparkling), but a tiny slice of production is made as a frizzante (a fizzy style with about 1-2.5 bars of pressure) and a tranquillo(still) version. The benefits of using the tank method are that it preserves the youthful fruity flavors (perfect for the aromatic Glera grape) whereas the traditional method used in Champagne and Franciacorta (frahn cha COR tah) produces more of a savory yeasty character in the wines. -

Il Vino Nella Storia Di Venezia Vigneti E Cantine Nelle Terre Dei Dogi Tra XIII E XXI Secolo Il Vino Nella Storia Di Venezia

Il vino nella storia di Venezia Vigneti e cantine nelle terre dei dogi tra XIII e XXI secolo Il vino nella storia di Venezia Biblos Biblos Venice and Viticulture Vines and Wines: the legacy of the Venetian Republic Venice and Viticulture Vines and Wines: the legacy of the Venetian Republic edited by Carlo Favero Using wine as one’s theme in recounting the long and complex history of Venice offers the reader an original insight into the past of the city and the territories it once ruled, a new way of looking at the monuments of a glorious past whose traces are still to be found in churches, art collections, libraries, public squares … and in gardens and vineyards. This is a book to read and a reference work for future consultation; a book that recounts not only history but also developments in technology and customs. The story told here covers the city’s links with the wine from its mainland and overseas possessions but also the wine produced within the lagoon itself. This is a relationship that dates back centuries, with the city’s magazeni and bacari serving at different points in history to satisfy the public taste for the different types of Malvasia and Raboso. And as the wine trade flourished, the Venetians showed all their entrepreneurial flair in serving markets throughout the known world. Indeed, it was in attempting to find even more distant markets for the Malvasia from Crete the Venetian nobleman Pietro Querini would end up shipwrecked on the Lofoten islands close to the Arctic circle, ironically discovering a new product himself: the stock fish (baccalà) that would then become very popular in Venice and the Venetian Republic. -

Buying Guide

BUYING GUIDE AUGUST 2012 Seifried Estate’s Brightwater Vineyard in Nelson is planted with Sauvignon Blanc, Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Grüner Veltliner, Pinot Noir and Zweigelt. 2 NEW ZEALAND 46 BURGUNDY 14 ARGENTINA 51 NORTHERN ITALY 21 CALIFORNIA 62 SPIRITS 36 OREGON 63 BEER 39 PORTUGAL FOR ADDITIONAL RATINGS AND REVIEWS, VISIT 42 ALSACE BUYINGGUIDE.WINEMAG.COM PHOTO © KEVIN JUDD WineMag.com | 1 NEW ZEALAND MORE DIVERSE THAN MEETS THE EYE s Managing Editor Joe Czerwinski explains in his feature on New One of the beautiful characteristics of Pinot Noir is it’s ability to convey Zealand whites this month (“New Zealand’s Best White Wines,” a sense of place, reflecting where the vine was grown more than other vari- A page 50), there is far more to the country’s vinous offerings than eties. Although New Zealand’s regional system is nowhere near as compli- the sea of Sauvignon Blanc that has flooded retail shelves. While the wines cated as Burgundy’s, there are distinct differences between the country’s have brought increased attention and awareness to New Zealand as a qual- Pinot Noir-producing regions, from the cheerful accessibility of Marlbor- ity winemaking region of the world, there is a vast wealth of additional va- ough to the elegance of Waipara and the savory earthiness of Martinbor- rieties and styles worth exploring. ough. The current emphasis on single vineyard wines or block selections The whites are well covered in Czerwinski’s article, as consumers are takes this sense of place even further, offering consumers the opportunity encouraged to search out other varieties that are extremely suitable to the to experience even more specialized and unique epressions—at a fraction country: Chardonnay, Pinot Gris and Riesling, just to name a few. -

Villa Sandi's Prosecco Superiore DOCG Valdobbiadene Extra Dry Is

Villa Sandi’s Prosecco Superiore DOCG Valdobbiadene Extra Dry is a beautiful wine that is testament to the exceptional quality of the wines from the DOCG area. It represents the tradition of excellence of the Villa Sandi estate, as well as acts as an elegant ambassador for a unique region of steep hills and fresh and lively wines. - Comprises fifteen communes that stretches over an area between the towns of Conegliano and Valdobbiadene. - Very hilly with steep, south-facing vineyard slopes at altitudes of 50-500 meters above sea level (164- 1640 feet). - 5,000 hectares (12,355 acres) of vineyards are entered in the official DOCG Register. - Mild climate, with cool winters and hot, dry summers. - Perfectly situated to take advantage of the cooling influences of the Dolomites and the moderating temperatures of the Adriatic. - The town of Valdobbiadene is at the heart of the actual production zone and has the greater concentration of hillside vineyards. - The individually numbered, salmon-colored Italian State seal guarantees that every stage of production was subject to strict controls. - DOCG designation granted in 2009. - Grapes: The wine is made from minimum 85% of Glera grapes and up to maximum 15% of Verdiso, Bianchetta, Perera and Glera Lunga grapes (varieties that have grown on the hills of Conegliano Valdobbiadene for centuries), or Pinot and Chardonnay. - Yield: DOCG yield is 13,500 kg per hectare (6 tons/acre). - One of three types of sparkling wine allowed in the DOCG: Brut, Extra Dry and Dry. - Of the three types, Extra Dry is the most traditional sparkling wine of the area.