Necdum Orbem Medium: Night in the Aeneid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meaht to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

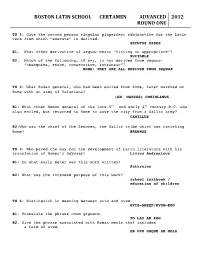

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Aeneas Study Questions

Mr. Pincus Latin I-B Nomen_________________ Aeneas Study Questions Prologue – The Judgement of Paris 1. Who made the prophecy that Paris would bring destrction to Troy? 2. Why did Queen Hecuba decide to exile Paris? 3. Who informed Paris that he must decide the contest? 4. Among what three goddesses (Roman) was Paris forced to choose? What did each offer him? 5. Who led the surviving Trojans out of the burning city? Who was his mother? Ch. 1 – Aeneas at Carthage 1. Why does Juno hate the Trojans? 2. What force was said to be stronger than the gods? 3. Who was the mortal father of Aeneas? 4. Whom does Juno ask to create a storm in order to destroy Aeneas and his ships? 5. Who is Aeneas’ faithful companion? 6. Whom does Jupiter tell Venus will be a descendant of Aeneas and will found Rome? 7. What is the name of Aeneas’ son? What is his other name? 8. Who is the Queen of Carthage? 9. At what city was Pygmalion, Dido’s brother, the king? 10. What does Venus do to ensure that Aeneas is well treated by Dido? Ch. 2 – The Last Hours of Troy 1. What is the subject of Book II of Vergil’s Aeneid? 2. What priest of Neptune warned the Trojans against the horse? 3. What is the name of the Greek “spy” who convinced the Trojans to take the horse into the city? 4. Who screamed a warning of doom about the horse? 5. Who appeared to Aeneas in a dream and warned him to leave Troy? 6. -

Mercury (Mythology) 1 Mercury (Mythology)

Mercury (mythology) 1 Mercury (mythology) Silver statuette of Mercury, a Berthouville treasure. Ancient Roman religion Practices and beliefs Imperial cult · festivals · ludi mystery religions · funerals temples · auspice · sacrifice votum · libation · lectisternium Priesthoods College of Pontiffs · Augur Vestal Virgins · Flamen · Fetial Epulones · Arval Brethren Quindecimviri sacris faciundis Dii Consentes Jupiter · Juno · Neptune · Minerva Mars · Venus · Apollo · Diana Vulcan · Vesta · Mercury · Ceres Mercury (mythology) 2 Other deities Janus · Quirinus · Saturn · Hercules · Faunus · Priapus Liber · Bona Dea · Ops Chthonic deities: Proserpina · Dis Pater · Orcus · Di Manes Domestic and local deities: Lares · Di Penates · Genius Hellenistic deities: Sol Invictus · Magna Mater · Isis · Mithras Deified emperors: Divus Julius · Divus Augustus See also List of Roman deities Related topics Roman mythology Glossary of ancient Roman religion Religion in ancient Greece Etruscan religion Gallo-Roman religion Decline of Hellenistic polytheism Mercury ( /ˈmɜrkjʉri/; Latin: Mercurius listen) was a messenger,[1] and a god of trade, the son of Maia Maiestas and Jupiter in Roman mythology. His name is related to the Latin word merx ("merchandise"; compare merchant, commerce, etc.), mercari (to trade), and merces (wages).[2] In his earliest forms, he appears to have been related to the Etruscan deity Turms, but most of his characteristics and mythology were borrowed from the analogous Greek deity, Hermes. Latin writers rewrote Hermes' myths and substituted his name with that of Mercury. However, there are at least two myths that involve Mercury that are Roman in origin. In Virgil's Aeneid, Mercury reminds Aeneas of his mission to found the city of Rome. In Ovid's Fasti, Mercury is assigned to escort the nymph Larunda to the underworld. -

Personification in Ovid's Metamorphoses

Personification in Ovid’s Metamorphoses: Inuidia, Fames, Somnus, Fama Maria Shiaele Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Classics August 2012 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. ©2012 The University of Leeds Maria Shiaele yia tovç yoveiç /lov for mum and dad IV Acknowledgements Throughout all these years of preparing this dissertation many people stood by my side and supported me intellectually, emotionally and financially to whom I would like to express my sincere thanks here. First of all, my deep gratitude goes to my supervisors Professor Robert Maltby and Dr Kenneth Belcher, for their unfailing patience, moral support, valuable criticism on my work and considerable insights. I thank them for believing in me, for being so encouraging during difficult and particularly stressful times and for generously offering their time to discuss concerns and ideas. It has been a great pleasure working with them and learning many things from their wide knowledge and helpful suggestions. Special thanks are owned to my thesis examiners, Dr Andreas Michalopoulos (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens) and Dr Regine May (University of Leeds), for their stimulating criticism and valuable suggestions. For any remaining errors and inadequacies I alone am responsible. Many thanks go to all members of staff at the Department of Classics at Leeds, both academic and secretarial, for making Leeds such a pleasant place to work in. -

Presents Semele

Presents __________________________________________________________________________ Semele By George Frideric Handel A RESOURCE PACK TO SUPPORT THE 2020 PRODUCTION The intention of this resource pack is to prepare students coming to see or taking part in tours or workshops focused on Semele Handel’s Semele Compiled by Callum Blackmore What is Opera? Opera is a type of theatre which combines drama, music, elements of dance or movement with exciting costumes and innovative set design. However, in opera, the actors are trained singers who sing their lines instead of speaking them. A librettist writes the libretto - the words that are to be sung, like a script. Often, the plots of the operas are taken from stories in books or plays. A composer writes the music for the singers and orchestra. An orchestra accompanies the singers. A conductor coordinates both the singers on stage and the musicians. An easy way to think of opera is a story told with music. In a lot of operas, the people on stage sing all the way through. Imagine having all your conversations by singing them! Opera Singers It takes a lot of training to become an opera singer. A lot of aspiring opera singers will take this route: Sing in choirs, volunteer for solos, take singing lessons, study singing and music at university, then audition for parts in operas. Opera singers hardly ever use a microphone, which means that they train their voices to be heard by audiences even over the top of orchestras. Singing opera can be very physical and tiring because of the effort that goes into making this very special sound. -

The Ovidian Soundscape: the Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses

The Ovidian Soundscape: The Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses Sarah Kathleen Kaczor Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Sarah Kathleen Kaczor All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Ovidian Soundscape: The Poetics of Noise in the Metamorphoses Sarah Kathleen Kaczor This dissertation aims to study the variety of sounds described in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and to identify an aesthetic of noise in the poem, a soundscape which contributes to the work’s thematic undertones. The two entities which shape an understanding of the poem’s conception of noise are Chaos, the conglomerate of mobile, conflicting elements with which the poem begins, and the personified Fama, whose domus is seen to contain a chaotic cosmos of words rather than elements. Within the loose frame provided by Chaos and Fama, the varied categories of noise in the Metamorphoses’ world, from nature sounds to speech, are seen to share qualities of changeability, mobility, and conflict, qualities which align them with the overall themes of flux and metamorphosis in the poem. I discuss three categories of Ovidian sound: in the first chapter, cosmological and elemental sound; in the second chapter, nature noises with an emphasis on the vocality of reeds and the role of echoes; and in the third chapter I treat human and divine speech and narrative, and the role of rumor. By the end of the poem, Ovid leaves us with a chaos of words as well as of forms, which bears important implications for his treatment of contemporary Augustanism as well as his belief in his own poetic fame. -

Ap Latin Summer Assignment

AP LATIN SUMMER ASSIGNMENT: Cardinal Gibbons High School Magistra Crabbe: 2018/2019 Assignment: Read and prepare for a test on Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Directions: ● Carefully read the introduction to the Aeneid written by Bernard Knox, and fill out the corresponding reflection questions. These questions will be collected and graded in August. Content from the introduction will be represented on the test in August. ● Carefully read the English Portions of the Syllabus from Virgil’s Aeneid. This is the entirety of Books I, II, IV, VI, VIII, and XII of Virgil’s Aeneid. Students should read the Revised Penguin Edition by David West. Hard copies of this book are available from Mrs. Crabbe in room 211. ● Fill out the corresponding study questions for each book. In August, these study questions will be collected and graded. ● Students will take a test on these readings before beginning the Latin portion of the AP Syllabus. Index of This Document: Introduction to the Aeneid by Bernard Knox: pp 126 Reading Questions for Introduction: pp 2734 Book I Reading Questions: pp 3543 Book II Reading Questions: pp 4449 Book IV Reading Questions: pp 5056 Book VI Reading Questions: pp 5764 Book VIII Reading Questions: pp 6568 Book XII Reading Questions: pp 6974 Suggested Reading Schedule: May 28th June 1st: Relax this week and recover from your finals. Drink lots of water. Get plenty of sleep. Spend time outside and do something fun with your friends. Help your parents around the house. -

AP® Latin Teaching the Aeneid

Professional Development AP® Latin Teaching The Aeneid Curriculum Module The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. © 2011 The College Board. College Board, Advanced Placement Program, AP, AP Central, SAT, and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Board. All other products and services may be trademarks of their respective owners. Visit the College Board on the Web: www.collegeboard.org. Contents Introduction................................................................................................. 1 Jill Crooker Minor Characters in The Aeneid...........................................................3 Donald Connor Integrating Multiple-Choice Questions into AP® Latin Instruction.................................................................... -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34 -

Mythology & Medicine Hospitalist Conference Dang Duong 4/1/19

Mythology & Medicine Hospitalist conference Dang Duong 4/1/19 “It means just what I choose it to mean - neither more nor less” – Humpty Dumpty 2 Ulralgia LFT TB Dr. Lown 3 JAK2 4 JANUS 5 Proteus mirabilis 6 PROTEUS VS Proteus Klippel–Trenaunay Syndrome 7 Proteus mirabilis Ascites 8 AEOLUS ASKOS ASCITES 9 Ammonia 10 AMON AMMONIA I am writing you in hopes of adding to your collection of medical etymologies. In this case, I came across a word that relates to my Egyptian heritage. I was just on my Neurology rotation and was reviewing neuroanatomy when I came across the regions of the Hippocampus, labeled CA1, CA2, CA3. Turns out CA stands for “Cornu Ammonis” which is Greek for the Horns of Amun. This is because the ancient Egyptian god Amun (later declared the one true god, Amun-Ra) was often portrayed with the head of a ram, whose horns resemble the shape of the hippocampus. Furthermore, I learned that Amun is also where the word “ammonia" comes from, due to depositions of ammonium chloride next to the Temple of Jupiter Ammon (the Roman’s version of Amun) in Ancient Libya. The salt was the result of years of excrement from camels parked outside the temple, and the Romans11 called it “sal ammoniacus,” a term revived many centuries later by a Swedish chemist. Venereal disease 12 APHRODITE VENUS 13 Subarachnoid hemorrhage 14 ARACHNE ARACHNOID MEMBRANE 15 Geriatrics Senile 16 Geras Senectus Geriatric Senile 17 Hypnosis Insomnia (lethargy) Euthanasia Thanatophobia 18 HYPNOS (somnus), THANATOS 19 Phantosmia 20 Phantasos 21 Morphine 22 MORPHEUS