Looking for Reality in Latin Love Elegy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Lady Lazarus" and Lady Chatterley

Plath Profiles 51 "Lady Lazarus" and Lady Chatterley W. K. Buckley, Indiana University Northwest For the October Conference on Plath at IUB, 2012 and Plath Profiles, Volume 5 Supplement, 20121 I. I remember my first reading of Plath, in college, at San Diego State University. We read, of course, all her famous poems from Ariel, as well as "The Jailor" ("I am myself. That is enough"[23]), "The Night Dances" ("So your gestures flake off" [29]). In my youth, on the beaches of Southern California, around a campfire, a group of us read to each other one night the poems of Plath, Ginsberg, Wilfred Owen, and D.H. Lawrence—seeing ourselves as prophets against war, despite that a few of us had been drafted to another oil adventure, including me. (Some of our friends had returned with no eyes or feet). We thought such famous poets could change America. They did not. (Despite Shelley's famous proclamation). Plath said in "Getting There": "Legs, arms, piled outside/The tent of unending cries—" (Ariel 57). Same old, same old historical mistakes: America, our 20th Century Roman Empire, we thought then. On the homefront, sexual activity in public places was then, as is now, monitored by our police, given our rape, murder, and "missing women" statistics, first or second in the world for such. Yet on that night, on that particular night, there was something "warmer" in the air on La Jolla Shores, as if we thought the world had calmed down for a moment. When the police arrived at our campfire, we all invited them to take it easy, since we saw ourselves as ordinary people, having ordinary activities in our ordinary bodies. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

I Have a Self to Recover: Sylvia Plath and the Literary Success of the Failed Suicide Clare Emily Clifford, Birmingham-Southern College

Plath Profiles 285 I Have a Self to Recover: Sylvia Plath and the Literary Success of the Failed Suicide Clare Emily Clifford, Birmingham-Southern College How shall I age into that state of mind? I am the ghost of an infamous suicide, My own blue razor rusting in my throat. Sylvia Plath, "Electra on Azalea Path" For most people, Sylvia Plath's work represents the epitome of suicidal poetry. The corpus of her poetic oeuvre forever captures the exhumation and resurrection of the material corpses it recomposes through figuration—fragments of bone from the colossal father, the "rubble of skull plates" in the cadaver room, Lady Lazarus' perpetual suicide strip-tease (Collected Poems 114). Plath's poetry is virtually a playground of decomposition; her speakers inhabit a "cramped necropolis," piecing together a ferocious love gathered among the graves (117). By collecting the force of this energy, Plath's work evidences a honed, disciplined voice of controlled extremity. This leads many critics, and often my students, to read into Plath's poetic intensity that she is an angry poet—considering her characters and poetic speakers' fierce energy as evidence of Plath's own anger. But as Plath's speakers wrestle with their anger on the page, they reveal the pain they feel and peace they fiercely and desperately wish for. This anger derives from their frustrated desire to find a lasting peace by recovering language from the constriction of suicidal thinking. Her speakers' rage represents the voice of anger turned against the self. Scavenging the ruins of the suicide's inner landscape—their inscape—Plath's speakers piece themselves together, death after self-inflicted death, becoming virtual experts at trying to recover from failed suicides.1 1 The field of Suicidology uses the term "completed suicide" to distinguish "individuals who have died by their own hand; have been sent to a morgue, funeral home, burial plot, or crematory; and are beyond any therapy" (Maris 15). -

Double Image : the Hughes-Plath Relationship As Told in Birthday Letters

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Double Image: The Hughes-Plath Relationship As Told in Birthday Letters. .A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy in English at Massey University Helen Jacqueline Cain 2002 II CONTENTS Abstract................................................ .iii Acknowledgements ....................................... .iv Introduction.............................................. 1 Chapter One -Ted Hughes on Trial. ......................... 10 Chapter Two - The Structure of Birthday Letters. ...............22 Chapter Three - Delivered of Yourself........................ .40 Chapter Four - The Man in Black. .................... 53 Chapter Five - Daddy Coming Up From Out of the Well......... 69 Chapter Six - Fixed Stars Govern a Life ........................74 Conclusion............................................... 80 Works Cited.............................................. 83 Works Consulted......................................... 87 iii ABSTRACT Proceeding from a close reading of both Birthdqy Letters and the poems of Sylvia Plath, and also from a consideration of secondary and biographical works, I argue that implicit within Birthdqy Letters is an explanation for Sylvia Plath's death and Ted Hughes's role in it. Birthdqy Letters is a collection of 88 poems written by Ted Hughes to his first wife, the poet Sylvia Plath, in the years following her death. There are two aspects to the explanation Ted Hughes provides. Both are connected to Sylvia Plath's poetry. Her development as a poet not only causes her death as told in Birthdqy Letters, but it also renders Ted Hughes incapable of helping her, because through her poetry he is made to adopt the role of Plath's father. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meaht to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Renaissance Receptions of Ovid's Tristia Dissertation

RENAISSANCE RECEPTIONS OF OVID’S TRISTIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gabriel Fuchs, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Frank T. Coulson, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Tom Hawkins Copyright by Gabriel Fuchs 2013 ABSTRACT This study examines two facets of the reception of Ovid’s Tristia in the 16th century: its commentary tradition and its adaptation by Latin poets. It lays the groundwork for a more comprehensive study of the Renaissance reception of the Tristia by providing a scholarly platform where there was none before (particularly with regard to the unedited, unpublished commentary tradition), and offers literary case studies of poetic postscripts to Ovid’s Tristia in order to explore the wider impact of Ovid’s exilic imaginary in 16th-century Europe. After a brief introduction, the second chapter introduces the three major commentaries on the Tristia printed in the Renaissance: those of Bartolomaeus Merula (published 1499, Venice), Veit Amerbach (1549, Basel), and Hecules Ciofanus (1581, Antwerp) and analyzes their various contexts, styles, and approaches to the text. The third chapter shows the commentators at work, presenting a more focused look at how these commentators apply their differing methods to the same selection of the Tristia, namely Book 2. These two chapters combine to demonstrate how commentary on the Tristia developed over the course of the 16th century: it begins from an encyclopedic approach, becomes focused on rhetoric, and is later aimed at textual criticism, presenting a trajectory that ii becomes increasingly focused and philological. -

Sidney Keyes: the War-Poet Who 'Groped for Death'

PINAKI ROY Sidney Keyes: The War-Poet Who ‘Groped For Death’ f the Second World War (1939-45) was marked by the unforeseen annihilation of human beings—with approximately 60 million military and civilian deaths (Mercatante 3)—the second global belligerence was also marked by an Iunforeseen scarcity in literary commemoration of the all-destructive belligerence. Unlike the First World War (1914-18) memories of which were recorded mellifluously by numerous efficient poets from both the sides of the Triple Entente and Central Powers, the period of the Second World War witnessed so limited a publication of war-writing in its early stages that the Anglo-Irish litterateur Cecil Day-Lewis (1904-72), then working as a publications-editor at the English Ministry of Information, was galvanised into publishing “Where are the War Poets?” in Penguin New Writing of February 1941, exasperatedly writing: ‘They who in folly or mere greed / Enslaved religion, markets, laws, / Borrow our language now and bid / Us to speak up in freedom’s cause. / It is the logic of our times, / No subject for immortal verse—/ That we who lived by honest dreams / Defend the bad against the worse’. Significantly, while millions of Europeans and Americans enthusiastically enlisted themselves to serve in the Great War and its leaders were principally motivated by the ideas of patriotism, courage, and ancient chivalric codes of conduct, the 1939-45 combat occurred amidst the selfishness of politicians, confusing international politics, and, as William Shirer notes, by unsubstantiated feelings of defeatism among world powers like England and France, who could have deterred the offensive Nazis at the very onset of hostilities (795-813). -

"Lady Lazarus" Is a Poem Commonly Understood to Be About Suicide. It Is Narrated by a Woman, and Mostly Addressed to an Unspecified Person

1 Lady Lazarus Sylvia Plath Summary "Lady Lazarus" is a poem commonly understood to be about suicide. It is narrated by a woman, and mostly addressed to an unspecified person. The narrator begins by saying she has "done it again." Every ten years, she manages to commit this unnamed act. She considers herself a walking miracle with bright skin, her right foot a "paperweight," and her face as fine and featureless as a "Jew linen". She addresses an unspecified enemy, asking him to peel the napkin from her face. She inquires whether he is terrified by the features he sees there. She assures him that her "sour breath" will vanish in a day. She is certain that her flesh will soon be restored to her face after having been sacrificed to the grave. She will then be a smiling thirty-year old woman. She will ultimately be able to die nine times, like a cat. Shehas just completed her third death. She will die once each decade. After each death, a "peanut-crunching crowd" shoves in to see her body unwrapped. She addresses the crowd directly, showing them she remains skin and bone, unchanged from who she was before. The first death occurred when she was ten, accidentally. The second death was intentional. She did not mean to return from it. Instead, she was as "shut as a seashell" until she was called back by people who then picked the worms off her corpse. She does not specifically identify how either death occurred. She believes that "Dying / Is an art, like everything else," and that she does it very well. -

The Vestal Virgins' Socio-Political Role and the Narrative of Roma

Krakowskie Studia z Historii Państwa i Prawa 2021; 14 (2), s. 127–151 doi:10.4467/20844131KS.21.011.13519 www.ejournals.eu/Krakowskie-Studia-z-Historii-Panstwa-i-Prawa Zeszyt 2 Karolina WyrWińsKa http:/orcid.org/0000-0001-8937-6271 Jagiellonian University in Kraków The Vestal Virgins’ Socio-political Role and the Narrative of Roma Aeterna Abstract Roman women – priestesses, patrician women, mysterious guardians of the sacred flame of goddess Vesta, admired and respected, sometimes blamed for misfortune of the Eternal City. Vestals identified with the eternity of Rome, the priestesses having a specific, unavailable to other women power. That power gained at the moment of a ritual capture (captio) and responsibilities and privileges resulted from it are the subject matter of this paper. The special attention is paid to the importance of Vestals for Rome and Romans in various historic moments, and to the purifying rituals performed by Vestals on behalf of the Roman state’s fortune. The study presents probable dating and possible causes of the end of the College of the Vestals in Rome. Keywords: Vesta, vestals, priesthood, priestesses, rituals Słowa kluczowe: Westa, westalki, kapłaństwo, kapłanki, rytuały Vesta and her priestesses Plutarch was not certain to which of the Roman kings attribute the implementation of the cult of Vesta in Rome, for he indicated that it had been done either by the legendary king- priest Numa Pompilius or even Romulus, who himself being a son of a Vestal Virgin, according to the legend, transferred the cult of the goddess from Alba Longa,1 which was contradicted by Livy’s work that categorically attributes the establishment of the Vestal Virgins to Numa by removing the priesthood structure from Alba Longa and providing it with support from the state treasury as well as by granting the priestesses numerous privileges”.2 Vesta, the daughter of Saturn and Ops became one of the most important 1 Plut. -

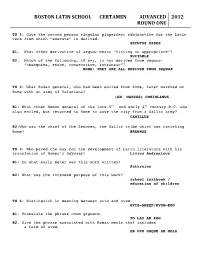

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Aeneas Study Questions

Mr. Pincus Latin I-B Nomen_________________ Aeneas Study Questions Prologue – The Judgement of Paris 1. Who made the prophecy that Paris would bring destrction to Troy? 2. Why did Queen Hecuba decide to exile Paris? 3. Who informed Paris that he must decide the contest? 4. Among what three goddesses (Roman) was Paris forced to choose? What did each offer him? 5. Who led the surviving Trojans out of the burning city? Who was his mother? Ch. 1 – Aeneas at Carthage 1. Why does Juno hate the Trojans? 2. What force was said to be stronger than the gods? 3. Who was the mortal father of Aeneas? 4. Whom does Juno ask to create a storm in order to destroy Aeneas and his ships? 5. Who is Aeneas’ faithful companion? 6. Whom does Jupiter tell Venus will be a descendant of Aeneas and will found Rome? 7. What is the name of Aeneas’ son? What is his other name? 8. Who is the Queen of Carthage? 9. At what city was Pygmalion, Dido’s brother, the king? 10. What does Venus do to ensure that Aeneas is well treated by Dido? Ch. 2 – The Last Hours of Troy 1. What is the subject of Book II of Vergil’s Aeneid? 2. What priest of Neptune warned the Trojans against the horse? 3. What is the name of the Greek “spy” who convinced the Trojans to take the horse into the city? 4. Who screamed a warning of doom about the horse? 5. Who appeared to Aeneas in a dream and warned him to leave Troy? 6. -

Allusions to Archaic Elegy in the Epigrams of Leonidas of Tarentum Alissa A

Allusions to Archaic Elegy in the Epigrams of Leonidas of Tarentum Alissa A. Vaillancourt (The Graduate Center of The City University of New York) Within the epigrams of the Greek Anthology, some scholars have identified a few elegiac elements. For example, in his article on the influence of archaic elegy on sympotic epigrams, Bowie proposes that Asclepiades, Callimachus, Hedylus and Posidippus “see themselves as in some respects reworking the early elegiac tradition.”1 I would like to add Leonidas of Tarentum to this list. In their commentary on Leonidas of Tarentum, Gow and Page identify two epigrams by Leonidas as elegies: 11 GP =AP 7.440 and 71 GP =AP 7.466.2 Using these elegies as my starting point, I will investigate how the poetry of Leonidas of Tarentum engages archaic elegy. I will begin by investigating the influence of archaic elegy on Leonidas with particular focus on the works of Mimnermus and Tyrtaeus. Through this investigation, I will show not only that the qualities of lamentation in archaic elegy influence Leonidas of Tarentum, but also that the didacticism that is common in archaic elegy is being refashioned by Leonidas to suit his own collection of epigrams. Leonidas applies elegiac didacticism in some of his poems in order to emphasize his own philosophy, which stresses the moribund nature of life. He refashions the elegy of Tyrtaeus by defining a sort of virtue in his epigrams, but instead of relating this virtue to valor earned through polemic pursuits for Sparta, Leonidas presents the virtue of the traveler, who is alone, jaded, and ready to embrace death.