University Microfilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period

Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period This volume is an investigation of how Augustine was received in the Carolingian period, and the elements of his thought which had an impact on Carolingian ideas of ‘state’, rulership and ethics. It focuses on Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims, authors and political advisers to Charlemagne and to Charles the Bald, respectively. It examines how they used Augustinian political thought and ethics, as manifested in the De civitate Dei, to give more weight to their advice. A comparative approach sheds light on the differences between Charlemagne’s reign and that of his grandson. It scrutinizes Alcuin’s and Hincmar’s discussions of empire, rulership and the moral conduct of political agents during which both drew on the De civitate Dei, although each came away with a different understanding. By means of a philological–historical approach, the book offers a deeper reading and treats the Latin texts as political discourses defined by content and language. Sophia Moesch is currently an SNSF-funded postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, working on a project entitled ‘Developing Principles of Good Govern- ance: Latin and Greek Political Advice during the Carolingian and Macedonian Reforms’. She completed her PhD in History at King’s College London. Augustine and the Art of Ruling in the Carolingian Imperial Period Political Discourse in Alcuin of York and Hincmar of Rheims Sophia Moesch First published 2020 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Published with the support of the Swiss National Science Foundation. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

LUCAN's CHARACTERIZATION of CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH By

LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY (Under the Direction of Thomas Biggs) ABSTRACT This thesis examines Caesar’s three extended battle exhortations in Lucan’s Bellum Civile (1.299-351, 5.319-364, 7.250-329) and the speeches that accompany them in an effort to discover patterns in the character’s speech. Lucan did not seem to develop a specific Caesarian style of speech, but he does make an effort to show the changing relationship between the General and his soldiers in the three scenes analyzed. The troops, initially under the spell of madness that pervades the poem, rebel. Caesar, through speech, is able to bring them into line. Caesar caters to the soldiers’ interests and egos and crafts his speeches in order to keep his army working together. INDEX WORDS: Lucan, Caesar, Bellum Civile, Pharsalia, Cohortatio, Battle Exhortation, Latin Literature LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY B.A., The College of Wooster, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth Talbot Neely All Rights Reserved LUCAN’S CHARACTERIZATION OF CAESAR THROUGH SPEECH by ELIZABETH TALBOT NEELY Major Professor: Thomas Biggs Committee: Christine Albright John Nicholson Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 -

The Reception of Cato Uticensis and the Confederate Lost Cause

The Reception of Cato Uticensis and the Confederate Lost Cause On June 4, 1914, the 106th anniversary of former Confederate President Jefferson Davis’ birth, sculptor Moses Ezekiel’s monument to the Confederacy, called New South, was unveiled in Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, DC. The monument is full of references to the ancient Roman world, especially in its sculptural style and the presence of a godly, pseudo- Minerva figure representing the New South. More curiously, Ezekiel inscribed the following quote from Book I of Lucan’s Pharsalia onto the monument underneath the seal of the Confederacy: “uictrix causa deis placuit sed uicta Catoni.” What does Cato have to do with the Lost Cause? Cato Uticensis was a Roman statesman, moralist, general, and avid defender of the Republic. Though he disliked both Pompey and Julius Caesar, he fought with Pompey against Caesar during the Civil War from 49 to 46 BCE. He became the de facto leader against Caesar after Pompey’s death in 48 but committed suicide in Utica after Caesar’s victory at Thrapsus. Robert Goar’s text detailing generally how a ‘legend’ formed around Cato in literature after his death from the first century BCE to the fifth century CE serves as the point of departure for this paper (Goar 1987). Goar concisely analyzes how the myth of Cato was adopted and transformed over time but does not analyze the impact or effects of this myth. The primary concern of this paper is on the legend’s impact— almost two millennia later. This paper explores the reception of the myths of both Cato Uticensis and his ancestor Cato Censorius by antebellum and postbellum Southern white Americans. -

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1

MYTHOLOGY – ALL LEVELS Ohio Junior Classical League – 2012 1. This son of Zeus was the builder of the palaces on Mt. Olympus and the maker of Achilles’ armor. a. Apollo b. Dionysus c. Hephaestus d. Hermes 2. She was the first wife of Heracles; unfortunately, she was killed by Heracles in a fit of madness. a. Aethra b. Evadne c. Megara d. Penelope 3. He grew up as a fisherman and won fame for himself by slaying Medusa. a. Amphitryon b. Electryon c. Heracles d. Perseus 4. This girl was transformed into a sunflower after she was rejected by the Sun god. a. Arachne b. Clytie c. Leucothoe d. Myrrha 5. According to Hesiod, he was NOT a son of Cronus and Rhea. a. Brontes b. Hades c. Poseidon d. Zeus 6. He chose to die young but with great glory as opposed to dying in old age with no glory. a. Achilles b. Heracles c. Jason d. Perseus 7. This queen of the gods is often depicted as a jealous wife. a. Demeter b. Hera c. Hestia d. Thetis 8. This ruler of the Underworld had the least extra-marital affairs among the three brothers. a. Aeacus b. Hades c. Minos d. Rhadamanthys 9. He imprisoned his daughter because a prophesy said that her son would become his killer. a. Acrisius b. Heracles c. Perseus d. Theseus 10. He fled burning Troy on the shoulder of his son. a. Anchises b. Dardanus c. Laomedon d. Priam 11. He poked his eyes out after learning that he had married his own mother. -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

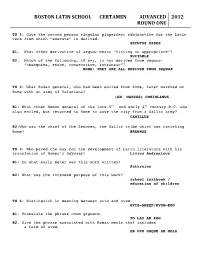

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Aeneas Study Questions

Mr. Pincus Latin I-B Nomen_________________ Aeneas Study Questions Prologue – The Judgement of Paris 1. Who made the prophecy that Paris would bring destrction to Troy? 2. Why did Queen Hecuba decide to exile Paris? 3. Who informed Paris that he must decide the contest? 4. Among what three goddesses (Roman) was Paris forced to choose? What did each offer him? 5. Who led the surviving Trojans out of the burning city? Who was his mother? Ch. 1 – Aeneas at Carthage 1. Why does Juno hate the Trojans? 2. What force was said to be stronger than the gods? 3. Who was the mortal father of Aeneas? 4. Whom does Juno ask to create a storm in order to destroy Aeneas and his ships? 5. Who is Aeneas’ faithful companion? 6. Whom does Jupiter tell Venus will be a descendant of Aeneas and will found Rome? 7. What is the name of Aeneas’ son? What is his other name? 8. Who is the Queen of Carthage? 9. At what city was Pygmalion, Dido’s brother, the king? 10. What does Venus do to ensure that Aeneas is well treated by Dido? Ch. 2 – The Last Hours of Troy 1. What is the subject of Book II of Vergil’s Aeneid? 2. What priest of Neptune warned the Trojans against the horse? 3. What is the name of the Greek “spy” who convinced the Trojans to take the horse into the city? 4. Who screamed a warning of doom about the horse? 5. Who appeared to Aeneas in a dream and warned him to leave Troy? 6. -

Iamze Gagua (Tbilisi)

Phasis 10 (I), 2007 Iamze Gagua (Tbilisi) FOR THE INTERPRETATION OF SOME DETAILS FROM THE ARGONAUT LEGEND ACCORDING TO THE ARGONAUTICA BY APOLLONIUS RHODIUS Admittedly, the Argonaut legend reflects ancient contacts of Hellenic sailors and Colchian tribes. They are evidenced by the myths about Aeetes’ leaving Corinth and residing in Aea-Colchis, Phrixus’ fleeing to the land of Aeetes, and Jason’s voyage to Colchis to retrieve the Golden Fleece. This legend, treated by ancient authors, was transformed as the time passed. Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica is the most extensive account of the Argonaut legend. The author referred to numerous sources and offered a lot of noteworthy information regarding particular episodes of the legend, the settlement of Colchian tribes and their customs and habits.1 The Argonautica presents a logical and coherent account of the Argonauts’ preparations for the perilous voyage, of the voyage itself, the arrival of the heroes in the land of Aeetes, Aea-Colchis (2), the obtaining of the Golden Fleece and their way back. I would like to dwell only on some of the details: 1. The main 1 See A. Urushadze, Ancient Colchis in the Argonaut Legend, Tbilisi 1964 (in Georgian). The Greek text of Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica, together with the Georgian version of it, was published, introduced, commented on and supplemented with an index by A. Urushadze, Tbilisi 1970. 2 It is obvious that Kutaia is connected with Kutaisi. Bearing in mind the Kartvelian etymology of kut- stem, the place-name can be interpreted as ‘a settlement on a vacant area between the mountains’ – R. -

Women, War and Wisdom

Syracuse University SURFACE at Syracuse University Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics College of Arts and Sciences 2016 Women, War and Wisdom Anne C. Leone Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/lll Part of the Italian Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Leone, Anne C. "Women, War and Wisdom1." in Vertical Readings in Dante's Comedy: Volume 2, George Corbett and Heather Webb (eds), Open Book Publishers, 2016. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE at Syracuse University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics by an authorized administrator of SURFACE at Syracuse University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. | George Corbett, Heather Webb p. 151-171 1 Many aspects of the eighteenth cantos of Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso resist meaningful comparison. The cantos differ significantly in terms of their dominant imagery, 1 of 28 motifs, structure, topography and astronomy, and characters. Nonetheless, despite these major differences, there are some suggestive parallels between the cantos that relate to their portrayal of women. Across the Eighteens, Dante alludes to female figures in classical, biblical and historical sources, which are often — but not always — negative and narrowly prescribed. Positive and negative images of women in the cantos share a number of characteristics and behaviours, and women are often defined in terms of their political or social functions — specifically in terms of how they aid or impede men engaged in military or heroic exploits, or in terms of their reproductive roles. -

Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: a Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas

The Internet Journal of Forensic Science ISPUB.COM Volume 3 Number 1 Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas Citation C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas. Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review. The Internet Journal of Forensic Science. 2007 Volume 3 Number 1. Abstract The aim of this review was to describe child abuse cases in ancient Greek mythology. Names like Hercules, Saturn, Aesculapius, Medea are very familiar. The stories can be divided into 3 categories: child abuse from gods to gods, from gods to humans and from humans to humans. In these stories children were abused in different ways and the reasons were of social, financial, political, religious, medical and sexual origin. The interpretations of the myths differed and the conclusions seemed controversial. Archaeologists, historians, and philosophers still try to bring these ancient stories into light in connection with the archaeological findings. The possibility for a dentist to face a child abuse case in the dental office nowadays proved the fact that child abuse was not only a phenomenon of the past but also a reality of the present. INTRODUCTION courses are easily available to everyone. Child abuse may be defined as any non-accidental trauma, On 1860 the forensic odontologist Ambroise Tardieu, neglect, failure to meet basic needs or abuse inflicted upon a referring to 32 cases, made a connection between subdural child by a caretaker that is beyond the acceptable norm of haematoma and abuse. In 1874 a church group in New York childcare in our culture. Abused children found in all 1 City took a child named Mary-Helen from home in which economic, social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds and she was being abused.