Presents Semele

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth)

The Hellenic Saga Gaia (Earth) Uranus (Heaven) Oceanus = Tethys Iapetus (Titan) = Clymene Themis Atlas Menoetius Prometheus Epimetheus = Pandora Prometheus • “Prometheus made humans out of earth and water, and he also gave them fire…” (Apollodorus Library 1.7.1) • … “and scatter-brained Epimetheus from the first was a mischief to men who eat bread; for it was he who first took of Zeus the woman, the maiden whom he had formed” (Hesiod Theogony ca. 509) Prometheus and Zeus • Zeus concealed the secret of life • Trick of the meat and fat • Zeus concealed fire • Prometheus stole it and gave it to man • Freidrich H. Fuger, 1751 - 1818 • Zeus ordered the creation of Pandora • Zeus chained Prometheus to a mountain • The accounts here are many and confused Maxfield Parish Prometheus 1919 Prometheus Chained Dirck van Baburen 1594 - 1624 Prometheus Nicolas-Sébastien Adam 1705 - 1778 Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus • Novel by Mary Shelly • First published in 1818. • The first true Science Fiction novel • Victor Frankenstein is Prometheus • As with the story of Prometheus, the novel asks about cause and effect, and about responsibility. • Is man accountable for his creations? • Is God? • Are there moral, ethical constraints on man’s creative urges? Mary Shelly • “I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion. Frightful must it be; for supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world” (Introduction to the 1831 edition) Did I request thee, from my clay To mould me man? Did I solicit thee From darkness to promote me? John Milton, Paradise Lost 10. -

Ornithological Approaches to Greek Mythology: the Case of the Shearwater

Ornithological Approaches to Greek Mythology: The Case of the Shearwater In the Odyssey 5.333-337, Ino-Leucothea rescues Odysseus from a terrifying storm while in the shape of an αἴθυια (aithyia) and gives him a magic veil so he can reach the land of the Phaeacians. But what bird is an aithyia, and, perhaps more importantly, can this information help us understand this passage of the Odyssey and other ancient texts where the bird appears? Many attempts at identifying Ino-Leucothea’s bird shape have been made. Lambin (2006) suggests that the name of byne that is occasionally (e.g. Lyc. Al. 757-761) applied to the goddess highlights her kourotrophic functions. In a more pragmatic way, Thompson (1895) suggests that the aithyia is a large gull such as Larus marinus. This identification is based on Aristotle (H.A. 7.542b) and Pliny (10.32) who report that the bird breeds in rocks by the sea in early spring. However, in a response to Thompson’s identification of a different bird, the ἐρωδιός (erôdios) as a heron, Fowler stresses that this bird nests in burrows by the sea (Pliny 10.126-127) and therefore must be Scopoli’s shearwater, Puffinus kuhli, now renamed Calonectris diomedea. The similarities between the aithyia and the erôdios prompted Thompson not only to reconsider his identification of the erôdios as a shearwater but also to argue that other bird names such as aithyia, memnôn, and mergus must also correspond to the shearwater. Thompson (1918) comes to this conclusion by taking a closer look at the mythological information concerning these birds. -

02-27-2020 Cosi Fan Tutte Eve.Indd

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART così fan tutte conductor Opera in two acts Harry Bicket Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte production Phelim McDermott Thursday, February 27, 2020 PM set designer 7:30–11:05 Tom Pye costume designer Laura Hopkins lighting designer Paule Constable The production of Così fan tutte was revival stage director made possible by generous gifts from Sara Erde William R. Miller, and John Sucich / Trust of Joseph Padula Additional funding was received from the The Walter and Leonore Annenberg Endowment Fund, and the National Endowment for the Arts general manager Peter Gelb Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and jeanette lerman-neubauer English National Opera music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin In collaboration with Improbable 2019–20 SEASON The 203rd Metropolitan Opera performance of WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S così fan tutte conductor Harry Bicket in order of vocal appearance ferrando skills ensemble Ben Bliss* Leo the Human Gumby Jonathan Nosan guglielmo Ray Valenz Luca Pisaroni Josh Walker Betty Bloomerz don alfonso Anna Venizelos Gerald Finley Zoe Ziegfeld Cristina Pitter fiordiligi Sarah Folkins Nicole Car Sage Sovereign Arthur Lazalde dorabella Radu Spinghel Serena Malfi despina continuo Heidi Stober harpsichord This performance Jonathan C. Kelly is being broadcast cello David Heiss live on Metropolitan Opera Radio on SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, February 27, 2020, 7:30–11:05PM RICHARD TERMINE / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Mozart’s Così Musical Preparation Joel Revzen, -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meaht to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Theban Walls in Homeric Epic Corinne Ondine Pache Trinity University, [email protected]

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Faculty Research Classical Studies Department 10-2014 Theban Walls in Homeric Epic Corinne Ondine Pache Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_faculty Part of the Classics Commons Repository Citation Pache, C. (2014). Theban walls in Homeric epic. Trends in Classics, 6(2), 278-296. doi:10.1515/tc-2014-0015 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TC 2014; 6(2): 278–296 Corinne Pache Theban Walls in Homeric Epic DOI 10.1515/tc-2014-0015 Throughout the Iliad, the Greeks at Troy often refer to the wars at Thebes in their speeches, and several important warriors fighting on the Greek side at Troy also fought at Thebes and are related to Theban heroes who besieged the Boeotian city a generation earlier. The Theban wars thus stand in the shadow of the story of war at Troy, another city surrounded by walls supposed to be impregnable. In the Odyssey, the Theban connections are less central, but nevertheless significant as one of our few sources concerning the building of the Theban walls. In this essay, I analyze Theban traces in Homeric epic as they relate to city walls. Since nothing explicitly concerning walls remains in the extant fragments of the Theban Cycle, we must look to Homeric poetry for formulaic and thematic elements that can be connected with Theban epic. -

Bulletin of the John Rylands Library

THE ORIGIN OF THE CULT OF DIONYSOS.1 . , BY J. RENDEL HARRIS, M.A., O.LITT., U...D., O.THEOL., ETC •• HON. FELLOW OF CLARE COLLECE, CAMBRIDGE ; DIRECTOR OF STUDIF.S AT THE WOODBROOKE SETTLEMENT, BIRMINGHAM. ODERN research is doing much to resolve the complicated and almost interminable riddles of the Greek and Latin M Mythologies. In another sense than the religious interpre tation, the gods of Olympus are fading away : as they fade from off the ethereal scene, the earlier forms out of which they were evolved come up again into view ; the Thunder-god goes back into the Thunder-man, or into the Thunder-bird or Thunder-tree ; Zeus takes the stately ~~ in vegetable life, of the Oak-tree, or if he must be Besh and blood he comes back as a Red-headed Woodpecker. Other ud similar evolutions are discovered and discoverable ; and the gods acquire a fresh interest when we have learnt their parentage. Sometimes, in the Zeus-worship at all events, we can see two forms of deity standing side by side, one coming on to the screen before the other has moved off ; the zoomorph or animal form co-existing and hardly displacing the phytomorph or plant fonn. One of the prettiest instances of this co-existence that I have dis covered came to my notice in connection with a study that I war. making of the place of bees in early religion. It was easy to see that the primitive human thinker had assigned a measure of sanctity to the bee, for he had found it in the hollows of his sacred tree : at the same time he had noticed that bees sprang from a little white larva. -

Christopher Ainslie Selected Reviews

Christopher Ainslie Selected Reviews Ligeti Le Grand Macabre (Prince Go-Go), Semperoper Dresden (November 2019) Counter Christopher Ainslie [w]as a wonderfully infantile Prince Go-Go ... [The soloists] master their games as effortlessly as if they were singing Schubertlieder. - Christian Schmidt, Freiepresse A multitude of excellent voices [including] countertenor Christopher Ainslie as Prince with pure, blossoming top notes and exaggerated drama they are all brilliant performances. - Michael Ernst, neue musikzeitung Christopher Ainslie gave a honeyed Prince Go-Go. - Xavier Cester, Ópera Actual Ainslie with his wonderfully extravagant voice. - Thomas Thielemann, IOCO Prince Go-Go, is agile and vocally impressive, performed by Christopher Ainslie. - Björn Kühnicke, Musik in Dresden Christopher Ainslie lends the ruler his extraordinary countertenor voice. - Jens Daniel Schubert, Sächsische Zeitung Christopher Ainslie[ s] rounded countertenor, which carried well into that glorious acoustic. - operatraveller.com Handel Rodelinda (Unulfo), Teatro Municipal, Santiago, Chile (August 2019) Christopher Ainslie was a measured Unulfo. Claudia Ramirez, Culto Latercera Handel Belshazzar (Cyrus), The Grange Festival (June 2019) Christopher Ainslie makes something effective out of the Persian conqueror Cyrus. George Hall, The Stage Counter-tenors James Laing and Christopher Ainslie make their mark as Daniel and Cyrus. Rupert Christiansen, The Telegraph Ch enor is beautiful he presented the conflicted hero with style. Melanie Eskenazi, MusicOMH Christopher Ainslie was impressive as the Persian leader Cyrus this was a subtle exploration of heroism, plumbing the ars as well as expounding his triumphs. Ashutosh Khandekar, Opera Now Christopher Ainslie as a benevolent Cyrus dazzles more for his bravura clinging onto the side of the ziggurat. David Truslove, OperaToday Among the puritanical Persians outside (then inside) the c ot a straightforwardly heroic countertenor but a more subdued, lighter and more anguished reading of the part. -

STONEFLY NAMES from CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Perla Jahr/Year: 1996 Band/Volume: 14 Autor(en)/Author(s): Ricker William E. Artikel/Article: Stonefly names from classical times 37-43 STONEFLY NAMES FROM CLASSICAL TIMES W. E. Ricker Recently I amused myself by checking the stonefly names that seem to be based on the names of real or mythological persons or localities of ancient Greece and Rome. I had copies of Bulfinch’s "Age of Fable," Graves; "Greek Myths," and an "Atlas of the Ancient World," all of which have excellent indexes; also Brown’s "Composition of Scientific Words," And I have had assistance from several colleagues. It turned out that among the stonefly names in lilies’ 1966 Katalog there are not very many that appear to be classical, although I may have failed to recognize a few. There were only 25 in all, and to get even that many I had to fudge a bit. Eleven of the names had been proposed by Edward Newman, an English student of neuropteroids who published around 1840. What follows is a list of these names and associated events or legends, giving them an entomological slant whenever possible. Greek names are given in the latinized form used by Graves, for example Lycus rather than Lykos. I have not listed descriptive words like Phasganophora (sword-bearer) unless they are also proper names. Also omitted are geographical names, no matter how ancient, if they are easily recognizable today — for example caucasica or helenica. alexanderi Hanson 1941, Leuctra. -

Poetic Language and Religion in Greece and Rome Edited by J

Poetic Language and Religion in Greece and Rome Edited by J. Virgilio García and Angel Ruiz This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by J. Virgilio García, Angel Ruiz and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5248-1, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5248-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ..................................................................................................... viii José Virgilio García Trabazo and Angel Ruiz Indo-European Poetic Language Gods And Vowels ....................................................................................... 2 Joshua T. Katz Some Linguistic Devices of the Greek Poetical Tradition ........................ 29 Jordi Redondo In Tenga Bithnua y la Lengua Angélica: Sus Fuentes y su Función ........ 39 Henar Velasco López Rumpelstilzchen: The Name of the Supernatural Helper and the Language of the Gods ............................................................................................... 51 Óscar M. Bernao Fariñas Religious Onomastics in Ancient Greece and Italy: Lexique, Phraseology and Indo-european Poetic Language ....................................................... -

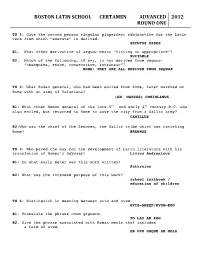

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Les Talens Lyriques the Ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, Which Takes Its

Les Talens Lyriques The ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, which takes its name from the subtitle of Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera Les Fêtes d’Hébé (1739), was formed in 1991 by the harpsichordist and conductor Christophe Rousset. Championing a broad vocal and instrumental repertoire, ranging from early Baroque to the beginnings of Romanticism, the musicians of Les Talens Lyriques aim to throw light on the great masterpieces of musical history, while providing perspective by presenting rarer or little known works that are important as missing links in the European musical heritage. This musicological and editorial work, which contributes to its renown, is a priority for the ensemble. Les Talens Lyriques perform to date works by Monteverdi (L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Il Ritorno d’Ulisse in patria, L’Orfeo), Cavalli (La Didone, La Calisto), Landi (La Morte d'Orfeo), Handel (Scipione, Riccardo Primo, Rinaldo, Admeto, Giulio Cesare, Serse, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano, Ariodante, Semele, Alcina), Lully (Persée, Roland, Bellérophon, Phaéton, Amadis, Armide, Alceste), Desmarest (Vénus et Adonis), Mondonville (Les Fêtes de Paphos), Cimarosa (Il Mercato di Malmantile, Il Matrimonio segreto), Traetta (Antigona, Ippolito ed Aricia), Jommelli (Armida abbandonata), Martin y Soler (La Capricciosa corretta, Il Tutore burlato), Mozart (Mitridate, Die Entführung aus dem Serail, Così fan tutte, Die Zauberflöte), Salieri (La Grotta di Trofonio, Les Danaïdes, Les Horaces, Tarare), Rameau (Zoroastre, Castor et Pollux, Les Indes galantes, Platée, Pygmalion), Gluck