Methodology Review and the Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sounding the Last Mile: Music and Capital Punishment in the United States Since 1976

SOUNDING THE LAST MILE: MUSIC AND CAPITAL PUNISHMENT IN THE UNITED STATES SINCE 1976 BY MICHAEL SILETTI DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2018 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jeffrey Magee, Chair and Director of Research Professor Gayle Magee Professor Donna A. Buchanan Associate Professor Christina Bashford ABSTRACT Since the United States Supreme Court reaffirmed the legality of the death penalty in 1976, capital punishment has drastically waxed and waned in both implementation and popularity throughout much of the country. While studying opinion polls, quantitative data, and legislation can help make sense of this phenomenon, careful attention to the death penalty’s embeddedness in cultural, creative, and expressive discourses is needed to more fully understand its unique position in American history and social life. The first known scholarly study to do so, this dissertation examines how music and sound have responded to and helped shape shifting public attitudes toward capital punishment during this time. From a public square in Chicago to a prison in Georgia, many people have used their ears to understand, administer, and debate both actual and fictitious scenarios pertaining to the use of capital punishment in the United States. Across historical case studies, detailed analyses of depictions of the death penalty in popular music and in film, and acoustemological research centered on recordings of actual executions, this dissertation has two principal objectives. First, it aims to uncover what music and sound can teach us about the past, present, and future of the death penalty. -

Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process Carolina Academic Press Law Casebook Series Advisory Board ❦

Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process Carolina Academic Press Law Casebook Series Advisory Board ❦ Gary J. Simson, Chairman Cornell Law School Raj K. Bhala The George Washington University Law School John C. Coffee, Jr. Columbia University School of Law Randall Coyne University of Oklahoma Law Center John S. Dzienkowski University of Texas School of Law Paul Finkelman University of Tulsa College of Law Robert M. Jarvis Shepard Broad Law Center Nova Southeastern University Vincent R. Johnson St. Mary’s University School of Law Thomas G. Krattenmaker Director of Research Federal Communications Commission Michael A. Olivas University of Houston Law Center Michael P. Scharf New England School of Law Peter M. Shane Dean, University of Pittsburgh School of Law Emily L. Sherwin University of San Diego School of Law John F. Sutton, Jr. University of Texas School of Law David B. Wexler University of Arizona College of Law Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process Second Edition Randall Coyne Professor of Law University of Oklahoma Lyn Entzeroth Law Clerk to Federal Magistrate Judge Bana Roberts Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina Copyright © 2001 by Randall Coyne and Lyn Entzeroth All Rights Reserved. ISBN: 0-89089-726-3 LCCN: 2001092360 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America Summary Table of Contents Table of Contents ix Table of Cases xxiii Table of Prisoners xxix List of Web Addresses xxxiii Preface to the Second Edition xxxv Preface to First Edition xxxvii Acknowledgments xxxix Chapter 1. -

Tacoma Community College 2006-07 Una Voce Student Essay Collection

Welcome to the seventh edition of Una Voce! Inside are essays which represent some of the best writing by Tacoma Community College students during the 2006/2007 academic year. Over forty well-written essays were submitted to the editors of this publication. We, the editorial staff of Una Voce, had the difficult task of narrowing the selection to the final essays published here. The talented students of Tacoma Community College should be extremely proud of their writing ability, as this publication is only a narrow sample of their talent. We would like to thank the students who submitted their work for publication, and also the gifted instructors who mentored and encouraged them. This year’s publication is the most political issue of Una Voce ever compiled. TCC’s students are very aware of the controversies swirling around them, and they have smart things to say about it all. From local debates, such as “The Necessity of Wal-Mart” and “Relocating the RAP and Lincoln Work Release Houses,” to global issues, such as the 9/11 terrorist attacks (Belting), homelessness (Entus), the USA Patriot Act (Miller), oil drilling in the Arctic (Govan), and high-stakes testing in education (Tetrault), this year’s writers are particularly good at analyzing and writing about hot issues. We believe this high level of critical thinking says a great deal about TCC students’ intellect and their concern for serious issues. However, humorous essays are included, as well; a good laugh is always welcome, and you will find a few inside. Una Voce has always been a showcase for across-the-academic-curriculum essays, and this year’s edition continues that tradition. -

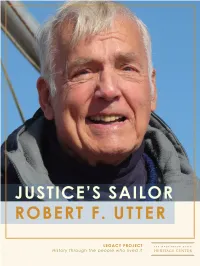

Robert F. Utter Final PDF.Indd

Robert F. Utter Research by John Hughes and Lori Larson Transcripti on by Lori Larson Interviews by John Hughes March 4, 2009 Hughes: Today The Legacy Project is with former Washington Supreme Court Justi ce Robert F. Utt er at his home on Cooper Point in Olympia. Justi ce Utt er served on the high court from Dec. 20, 1971, unti l his resignati on on April 24, 1995, to protest the death penalty. Besides his half-century career in the law and his internati onal acti vism for peace and justi ce, Justi ce Utt er has writt en widely about Justi ce Utt er on the Washington Supreme Court bench, 1972 his spiritual journey. Judge, I understand that Willi Unsoeld, the legendary mountain climber, was one of your heroes. Utt er: Willi was a neighbor. He always told me he had more sacred encounters in the mountains than in any church. And he said there were “only two illicit questi ons in philosophy – ‘What if?’ and ‘Why?’ He said they’re illicit because there’s no answer, and to dwell on them only leads to madness!” There have been two gurus in my life – Willi was one, and Jim Houston was the other. Houston is a remarkable man. He taught with C.S. Lewis at Oxford. Hughes: Speaking of heroes: C.S. Lewis. What a writer! Utt er: There is a beauti ful piece that Dr. Houston wrote — “Living in a Suff ering World.” It’s in the book called I Believe in the Creator. Hughes: It’s pronounced “whose-ton”? Utt er: Yes. -

Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process 00 Coyne 4E Final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page Ii

00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page i Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page ii Carolina Academic Press Law Advisory Board ❦ Gary J. Simson, Chairman Dean, Mercer University School of Law Raj Bhala University of Kansas School of Law Davison M. Douglas Dean, William and Mary Law School Paul Finkelman Albany Law School Robert M. Jarvis Shepard Broad Law Center Nova Southeastern University Vincent R. Johnson St. Mary’s University School of Law Peter Nicolas University of Washington School of Law Michael A. Olivas University of Houston Law Center Kenneth L. Port William Mitchell College of Law H. Jefferson Powell The George Washington University Law School Michael P. Scharf Case Western Reserve University School of Law Peter M. Shane Michael E. Moritz College of Law The Ohio State University 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page iii Capital Punishment and the Judicial Process fourth edition Randall Coyne Frank Elkouri and Edna Asper Elkouri Professor of Law University of Oklahoma College of Law Lyn Entzeroth Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Academic Affairs University of Tulsa College of Law Carolina Academic Press Durham, North Carolina 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page iv Copyright © 2012 Randall Coyne, Lyn Entzeroth All Rights Reserved ISBN: 978-1-59460-895-7 LCCN: 2012937426 Carolina Academic Press 700 Kent Street Durham, North Carolina 27701 Telephone (919) 489-7486 Fax (919) 493-5668 www.cap-press.com Printed in the United States of America 00 coyne 4e final 6/6/12 2:50 PM Page v Summary of Contents Table of Cases xxiii Table of Prisoners xxix List of Web Addresses xxxv Preface to the Fourth Edition xxxvii Preface to the Third Edition xxxix Preface to the Second Edition xli Preface to the First Edition xliii Acknowledgments xlv Chapter 1 • The Great Debate Over Capital Punishment 3 A. -

Fiscal Note Package 31143

Multiple Agency Fiscal Note Summary Bill Number: 6283 SB Title: Death penalty elimination Estimated Cash Receipts Agency Name 2011-13 2013-15 2015-17 GF- State Total GF- State Total GF- State Total Office of Attorney General Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion." Total $ 0 0 0 0 0 0 Estimated Expenditures Agency Name 2011-13 2013-15 2015-17 FTEs GF-State Total FTEs GF-State Total FTEs GF-State Total Administrative Office Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. of the Courts Office of Public Fiscal note not available Defense Office of Attorney Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. General Caseload Forecast .0 0 0 .0 0 0 .0 0 0 Council Department of Non-zero but indeterminate cost and/or savings. Please see discussion. Corrections Total 0.0 $0 $0 0.0 $0 $0 0.0 $0 $0 Local Gov. Courts * Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion. Local Gov. Other ** Non-zero but indeterminate cost. Please see discussion. Local Gov. Total Estimated Capital Budget Impact NONE Prepared by: Adam Aaseby, OFM Phone: Date Published: 360-902-0539 Final 1/27/2012 * See Office of the Administrator for the Courts judicial fiscal note ** See local government fiscal note FNPID 31143 : FNS029 Multi Agency rollup Judicial Impact Fiscal Note Bill Number: 6283 SB Title: Death penalty elimination Agency: 055-Admin Office of the Courts Part I: Estimates No Fiscal Impact Estimated Cash Receipts to: Account FY 2012 FY 2013 2011-13 2013-15 2015-17 Counties Cities Total $ Estimated Expenditures from: Non-zero but indeterminate cost. -

Youth Protest Bank of America Funding Fossil Fuels

The New Hampshire Gazette, Friday, May 21, 2021 — Page 1 We Put the Vol. CCLXV, No. 18 The New Hampshire Gazette May 21, 2021 The Nation’s Oldest Newspaper™ • Editor: Steven Fowle • Founded 1756 by Daniel Fowle Free! PO Box 756, Portsmouth, NH 03802 • [email protected] • www.nhgazette.com in Free Press The Fortnightly Rant The Storm’s Not Coming—It’s Here ew Englanders are familiar lished that a person’s right to in- with the scene: video shows fluence elections should increase in Nrain falling sideways and random proportion to their net worth. objects flying through the air. Crash- Shelby County v. Holder, in 2013, ing waves beat furiously against the ruled that, since the Republican Par- shore. Finally the land crumbles. A ty had not been found guilty recent- house falls, beaten to smithereens, ly of criminally intimidating poor, and ceases to exist. non-white voters, the law that had Traditionally it’s been a hurricane been preventing them from doing so or a bad nor’easter, and the process could now be discarded. takes a few hours. Lately, it’s politics. Now that they have achieved such The end hasn’t come for America’s dominance, one might think that democracy yet, but things don’t look Republicans could relax a bit. Cer- particularly good. tainly life in these allegedly United Nobody builds on the edge of a States has been relatively and re- cliff, of course.* Things just creep up freshingly placid since Jack Dorsey on you: the Atlantic Ocean, the Re- threw a certain someone off Twit- publican Party…. -

IN RE BLODGETT 112 S. Ct. 674 (1992), 5 Cap

Capital Defense Journal Volume 5 | Issue 1 Article 12 Fall 9-1-1992 IN RE BLODGETT 112 .S Ct. 674 (1992) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlucdj Part of the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation IN RE BLODGETT 112 S. Ct. 674 (1992), 5 Cap. Def. Dig. 22 (1992). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlucdj/vol5/iss1/12 This Casenote, U.S. Supreme Ct. is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capital Defense Journal by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Page 22 - CapitalDefense Digest, Vol. 5, No. I IN RE BLODGETT 112 S. Ct. 674 (1992) United States Supreme Court FACTS HOLDING In 1982, a Washingtonjury convicted Charles Rodman Campbell of The Supreme Court denied the state's mandamus request.4 The multiple murders and sentenced him to death. Direct appeals, t a state Court held that the state should have asked the Court of Appeals to vacate habeas petition, and a federal habeas petition2 all failed to provide any or modify its 1991 order before proceeding to the United States Supreme relief to Campbell. After Campbell filed a second federal habeas petition Court with its request.5 However, the Court in Blodgett took a strong in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington position on stays of executions and "explicitly" held that "[ifn a capital in 1989, the district court held a hearing and issued a written opinion case the grant of a stay of execution directed to a State by a federal court denying a stay or other relief to the defendant. -

ABC Amber Text Converter

ABC Amber Text Converter Unregistered, http://www.thebeatlesforever.com/processtext/ a fever in the heart [052-066-4.9] by ann rule. Author's Note. It has been said that there are no new stories under the sun. Even those dramas and tragedies that are true are only a reprise of something that has happened before. I suspect that is an accurate analysis. In this third volume of my true crime files, I note that I have either subconsciously or inadvertently chosen four cases that share a common theme: personal betrayal. Since I am a great believer in the premise that we do nothing accidentally, it must be the right time to contemplate homicides that occur because the victim or victims have been betrayed by someone they have come to trust. In most of the following cases, the victims have believed in their killers over a long time, in one case, the victims have put their faith too quickly in the wrong men. There is something especially heartbreaking about love and friendships betrayed. The thought that some of the victims in this book must have recognized that betrayal at the very last moments of their lives may be difficult to cope with. In the final two cases, the system trusted a criminal's rehabilitation and innocent people paid for this mistake. All serve to remind us that things are seldom what they seem. And to be wary. The title case in A Fever in the Heart occurred very early in my career as a true crime writer, so early, in fact, that I felt I had neither the courage nor the technical skill to undertake a book. -

Snohomish County Death Penalty Cases Under Current Law

HeraldNet: Print Article Page 1 of 4 Everett, Washington Published: Tuesday, February 11, 2014, 5:37 p.m. Snohomish County death penalty cases under current law << Prev Next >> • Herald file photo / 1982 Charles Rodman Campbell was hanged in 1994. • Herald file Charles Ben Finch was sentenced to die in 1994. His sentence was later overturned. http://www.heraldnet.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20140211/NEWS01/140219808/Sn... 2/12/2014 HeraldNet: Print Article Page 2 of 4 • Herald file photo / April 25, 1997 Richard Mathew Clark leaves the courtroom after being sentenced to die. • Herald file photo Condemned murderer James Elledge hides his face by hanging his head as he is led through a Snohomish County Courthouse. Elledge died by lethal injection in 2001. • Herald file photo / 2003 http://www.heraldnet.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20140211/NEWS01/140219808/Sn... 2/12/2014 HeraldNet: Print Article Page 3 of 4 Barbara Opel appears in court on April 7, 2003. A jury opted for a life sentence rather than the death penalty for Opel. • Genna Martin / The Herald Byron Scherf stands with his lawyers after his death penalty sentencing is read by Judge George Appel in May 2013 in Snohomish County Superior Court. Herald Staff The cases of six convicted murderers show how the death penalty played out in Snohomish County since the state’s current capital punishment law was approved in 1981: • Charles Rodman Campbell was hanged in 1994 for the throat slashing murders of two women and a girl near Clearview in 1982. Campbell raped one of the women about a decade before the killings. -

'Wherever and Whenever'

baylorlariat com SPORTS p. 5 Baylor men’s basketball was defeated by WVU with a final score of 66-64. BaylorLariat WE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE Wednesday | January 29, 2014 Body of bridge worker found after fall By Paula Ann Solis rived on scene at 8 p.m. and pronounced a manlift, which is a scaffold with a bucket workers on site rescued him when he sur- East Texas Medical Center EMS and Texas Staff Writer the person as dead at 8:17 p.m. The name or platform, when, for reasons unknown, faced. Providence Hospital medical staff is Parks and Wildlife responded to the call of the man has not been released because it went into the water with both men teth- currently treating him for hypothermia. for assistance. Divers found what may be the body of a positive identity could not be confirmed ered to it. It fell into an estimated 20 ft. of Swanton said he suffered no other known Texas Parks and Wildlife game wardens a missing construction worker Tuesday on scene. water. injuries. are using side sonar search methods to lo- evening in the Brazos River behind the Sgt. W. Patrick Swanton, the public in- The other man, whose identity has Authorities were alerted of the inci- cate the body, although Swanton said the McLane Stadium building site. formation officer for the Waco Police De- also not been released, was able to release dent shortly after 4 p.m. The Baylor -Po Justice of the Peace Kristi DeCluitt ar- partment, said two men were working on himself from the lift and construction lice Department, Waco Fire Department, SEE BRIDGE, page 6 In the ‘Wherever and whenever’ works Local developer to give housing opportunity to grad students By Jordan Corona Staff Writer A new idea in South Waco may give a special housing opportunity to Truett and social work graduate stu- dents. -

Dodd, Westley Allan, Steinhurst, Lori, & Rose, John (1994)

Westley Allan Dodd “The Vancouver Child Killer” Information summarized by Aleisha Branch, Holly Bryan, Maria Giovenco, Nicole Nichols and Elizabeth Yeatts Department of Psychology Radford University Radford, VA 24142-6946 Date Age Life Event 07/03/1961 0 Dodd was born in Toppenish, Washington and would be the oldest of three children 06/05/1962 11 Dodd’s brother was born and he began bathing and sleeping with him. Dodd months would continue to bathe with him until he was 7-years-old and sleeping with him in the same bed until he was 10-years-old. Dodd denies any sexual contact with his brother. 05/29/1965 3 Dodd’s sister was born and the only memory he has of her being a baby was his mom breastfeeding her. 1966 4 Dodd stated that when he was in the hospital to have his tonsils removed, he was embarrassed after wetting his pants when his mom was getting him ready for surgery. June, 1970 8 While at his 8-year-old cousin’s house, Dodd and his cousin sexually experimented by touching their penises together. September, 9 Dodd’s mom made him change his pants two times in front of two of his aunts and 1970 he stated that he felt a lot of embarrassment from this event. 1971 10 Dodd was first rejected by a girl when he pulled down his pants in front of his 6- year-old neighbor; she refused to look at him. Dodd later stated in his letters to a police official that he believes this is the moment he began preferring boys over girls.