Europe Between the Languages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Contact at the Romance-Germanic Language Border

Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Other Books of Interest from Multilingual Matters Beyond Bilingualism: Multilingualism and Multilingual Education Jasone Cenoz and Fred Genesee (eds) Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (eds) Bilingualism: Beyond Basic Principles Jean-Marc Dewaele, Alex Housen and Li wei (eds) Can Threatened Languages be Saved? Joshua Fishman (ed.) Chtimi: The Urban Vernaculars of Northern France Timothy Pooley Community and Communication Sue Wright A Dynamic Model of Multilingualism Philip Herdina and Ulrike Jessner Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism Colin Baker and Sylvia Prys Jones Identity, Insecurity and Image: France and Language Dennis Ager Language, Culture and Communication in Contemporary Europe Charlotte Hoffman (ed.) Language and Society in a Changing Italy Arturo Tosi Language Planning in Malawi, Mozambique and the Philippines Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Planning in Nepal, Taiwan and Sweden Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. and Robert B. Kaplan (eds) Language Planning: From Practice to Theory Robert B. Kaplan and Richard B. Baldauf, Jr. (eds) Language Reclamation Hubisi Nwenmely Linguistic Minorities in Central and Eastern Europe Christina Bratt Paulston and Donald Peckham (eds) Motivation in Language Planning and Language Policy Dennis Ager Multilingualism in Spain M. Teresa Turell (ed.) The Other Languages of Europe Guus Extra and Durk Gorter (eds) A Reader in French Sociolinguistics Malcolm Offord (ed.) Please contact us for the latest book information: Multilingual Matters, Frankfurt Lodge, Clevedon Hall, Victoria Road, Clevedon, BS21 7HH, England http://www.multilingual-matters.com Language Contact at the Romance–Germanic Language Border Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns MULTILINGUAL MATTERS LTD Clevedon • Buffalo • Toronto • Sydney Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Language Contact at Romance-Germanic Language Border/Edited by Jeanine Treffers-Daller and Roland Willemyns. -

Managing France's Regional Languages

MANAGING FRANCE’S REGIONAL LANGUAGES: LANGUAGE POLICY IN BILINGUAL PRIMARY EDUCATION IN ALSACE Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michelle Anne Harrison September 2012 Abstract The introduction of regional language bilingual education in France dates back to the late 1960s in the private education system and to the 1980s in the public system. Before this time the extensive use of regional languages was forbidden in French schools, which served as ‘local centres for the gallicisation of France’ (Blackwood 2008, 28). France began to pursue a French-only language policy from the time of the 1789 Revolution, with Jacobin ideology proposing that to be French, one must speak French. Thus began the shaping of France into a nation-state. As the result of the official language policy that imposed French in all public domains, as well as extra-linguistic factors such as the Industrial Revolution and the two World Wars, a significant language shift occurred in France during the twentieth century, as an increasing number of parents chose not to pass on their regional language to the next generation. In light of the decline in intergenerational transmission of the regional languages, Judge (2007, 233) concludes that ‘in the short term, everything depends on education in the [regional languages]’. This thesis analyses the development of language policy in bilingual education programmes in Alsace; Spolsky’s tripartite language policy model (2004), which focuses on language management, language practices and language beliefs, will be employed. In spite of the efforts of the State to impose the French language, in Alsace the traditionally non-standard spoken regional language variety, Alsatian, continued to be used widely until the mid-twentieth century. -

Texas Alsatian

2017 Texas Alsatian Karen A. Roesch, Ph.D. Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Indianapolis, Indiana, USA IUPUI ScholarWorks This is the author’s manuscript: This is a draft of a chapter that has been accepted for publication by Oxford University Press in the forthcoming book Varieties of German Worldwide edited by Hans Boas, Anna Deumert, Mark L. Louden, & Péter Maitz (with Hyoun-A Joo, B. Richard Page, Lara Schwarz, & Nora Hellmold Vosburg) due for publication in 2016. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu Texas Alsatian, Medina County, Texas 1 Introduction: Historical background The Alsatian dialect was transported to Texas in the early 1800s, when entrepreneur Henri Castro recruited colonists from the French Alsace to comply with the Republic of Texas’ stipulations for populating one of his land grants located just west of San Antonio. Castro’s colonization efforts succeeded in bringing 2,134 German-speaking colonists from 1843 – 1847 (Jordan 2004: 45-7; Weaver 1985:109) to his land grants in Texas, which resulted in the establishment of four colonies: Castroville (1844); Quihi (1845); Vandenburg (1846); D’Hanis (1847). Castroville was the first and most successful settlement and serves as the focus of this chapter, as it constitutes the largest concentration of Alsatian speakers. This chapter provides both a descriptive account of the ancestral language, Alsatian, and more specifically as spoken today, as well as a discussion of sociolinguistic and linguistic processes (e.g., use, shift, variation, regularization, etc.) observed and documented since 2007. The casual observer might conclude that the colonists Castro brought to Texas were not German-speaking at all, but French. -

Rémi Pach the LINGUISTIC MINORITIES of FRANCE France Is

ISSN 0258-2279 = Literator 7 (1986) Rémi Pach THE LINGUISTIC MINORITIES OF FRANCE ABSTRACT Although France is one of the most centralized countries in Europe, its ap parent unity must not conceal that it is made up of many linguistic groups, and that French has only in recent years succeeded in becoming the com mon language of all the French. The situation of each one of the seven non official languages of France is at first examined. The problem is then situ ated in its historical context, with the emphasis falling on why and how the French state tried to destroy them. Although the monarchy did not go much further than to impose French as the language of the administration, the revolutionary period was the beginning of a deliberate attempt to substi tute French for the regional languages even in informal and oral usage. This was really made possible when education became compulsory: the school system was then the means of spreading French throughout the country. Nowadays the unity of France is no longer at stake, but its very identity is being threatened by the demographic weight, on French soil, of the im migrants from the Third-World. France is without any possible doubt the most heterogeneous country in Western Europe, as it includes no less than seven linguistic minori ties : Corsicans, Basques, Catalans, Occitans, Alsatians, Flemish and 85 THE LANGUAGES OF FRANCE i?|n.niviANnl NON-ROMANnS IDinMS H I^^CO H SrCA H ^g] CATAWH DIAI.CCT8 o r OCCITAN 86 Bretons.' Most of these were conquered by means of wars. -

Strasbourg & the History of the Book: Five Centuries of German Printed Books and Manuscripts

Strasbourg & the History of the Book: Five centuries of German printed books and manuscripts Taylor Institution Library St Giles’, University of Oxford 11 July – 30 September 2009 Mon ‐ Fri 9 ‐ 5, Sat 10‐4 1 October – 4 November 2009 Mon ‐ Fri 9 ‐ 7, Sat 10‐4 closed Saturday 29 August to Tuesday 8 September Curator: Professor N.F. Palmer. Organised by the Taylor Institution Library, in collaboration with the sub‐Faculty of German, University of Oxford. Strasbourg and the History of the Book: Five Centuries of German Printed Books and Manuscripts 1: Strasbourg: The City’s Medieval Heritage 2: Strasbourg: A Centre of Early Printing 3: Strasbourg and Upper Rhenish Humanism 4: Der Grüne Wörth 5: Books from Strasbourg from the 1480s to the 1980s 6: History, Literature and Language 2 STRASBOURG, Case 1: Strasbourg: The City’s Medieval Heritage The Burning of the Strasbourg Library in 1870 On 24 August 1870 the Strasbourg town library, housed in the former Dominican church, the Temple‐Neuf, was burned out by German incendiary bombs, destroying the greater part of the book heritage from the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. Strasbourg, as the principal city of Alsace, had been German throughout the Middle Ages and Reformation period until the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, when Alsace fell to France (though Strasbourg did not fully become a French city until 1681). After France’s defeat in the Franco‐Prussian War in 1871, which was the occasion of the bombing, Alsace‐ Lorraine was incorporated into the German Empire, and the library was rebuilt and restocked. -

Vocalisations: Evidence from Germanic Gary Taylor-Raebel A

Vocalisations: Evidence from Germanic Gary Taylor-Raebel A thesis submitted for the degree of doctor of philosophy Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex October 2016 Abstract A vocalisation may be described as a historical linguistic change where a sound which is formerly consonantal within a language becomes pronounced as a vowel. Although vocalisations have occurred sporadically in many languages they are particularly prevalent in the history of Germanic languages and have affected sounds from all places of articulation. This study will address two main questions. The first is why vocalisations happen so regularly in Germanic languages in comparison with other language families. The second is what exactly happens in the vocalisation process. For the first question there will be a discussion of the concept of ‘drift’ where related languages undergo similar changes independently and this will therefore describe the features of the earliest Germanic languages which have been the basis for later changes. The second question will include a comprehensive presentation of vocalisations which have occurred in Germanic languages with a description of underlying features in each of the sounds which have vocalised. When considering phonological changes a degree of phonetic information must necessarily be included which may be irrelevant synchronically, but forms the basis of the change diachronically. A phonological representation of vocalisations must therefore address how best to display the phonological information whilst allowing for the inclusion of relevant diachronic phonetic information. Vocalisations involve a small articulatory change, but using a model which describes vowels and consonants with separate terminology would conceal the subtleness of change in a vocalisation. -

Book of Abstracts

Book of Abstracts 3rd conference on Contested Languages in the Old World (CLOW3) University of Amsterdam, 3–4 May 2018 CLOW3 Scientific Committee: Federico CLOW3 has received financial support from Gobbo (University of Amsterdam); Marco the research programme ‘Mobility and Tamburelli (Bangor University); Mauro Tosco Inclusion in Multilingual Europe’ (MIME, EC (University of Turin). FP7 grant no. 613334). CLOW3 Local Organizing Committee: Federico Gobbo; Sune Gregersen; Leya Egilmez; Franka Bauwens; Wendy Bliekendaal; Nour Efrat-Kowalsky; Nadine van der Maas; Leanne Staugaard; Emmanouela Tsoumeni; Samuel Witteveen Gómez. Additional support has been provided by John Benjamins Publishing Company. CLOW3 Book of Abstracts edited by Sune Gregersen. Abstracts © The Author(s) 2018. 2 Table of contents Paper presentations Ulrich Ammon (keynote) 4 Andrea Acquarone & Vittorio Dell’Aquila 5 Astrid Adler, Andrea Kleene & Albrecht Plewnia 6 Márton András Baló 7 Guillem Belmar, Nienke Eikens, Daniël de Jong, Willemijn Miedma & Sara Pinho 8 Nicole Dołowy-Rybińska & Cordula Ratajczak 9 Guilherme Fians 10 Sabine Fiedler 11 Federico Gobbo 12 Nanna Haug Hilton 13 Gabriele Iannàccaro & Vittorio Dell’Aquila 14 G. T. Jensma 15 Juan Jiménez-Salcedo 16 Aurelie Joubert 17 Petteri Laihonen 18 Patrick Seán McCrea 19 Leena Niiranen 20 Yair Sapir 21 Claudia Soria 22 Ida Stria 23 Marco Tamburelli & Mauro Tosco 24 Poster presentations Eva J. Daussà, Tilman Lanz & Renée Pera-Ros 25 Vittorio Dell’Aquila, Ida Stria & Marina Pietrocola 26 Sabine Fiedler & Cyril Brosch 27 Daniel Gordo 28 Olga Steriopolo & Olivia Maky 29 References 30 Index of languages 34 3 Keynote: From dialects and languages to contested languages Ulrich Ammon (University of Duisburg-Essen) The presentation begins with the explication of concepts which are fundamental and which have to be defined with sufficient clarity for the following thoughts, because terminology and concepts vary widely in the relevant literature. -

Ratification

READY FOR RATIFICATION Vol. 1 Early compliance of non-States Parties with the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages A Handbook with twenty proposed instruments of ratification Volume 1: Regional or Minority Languages in non-States Parties Compliance of National Legislation with the ECRML Ewa Chylinski Mahulena Hofmannová (eds.) Proposals for Instruments of Ratification READY FOR RATIFICATION Vol. 1 Imprint Preface Publisher: European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) For a number of years, the European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) and the Council of Europe co-operated on the © ECMI 2011 publication of a handbook series on various minority issues. The topical areas were legal provisions for the protection and promotion of minority rights under the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCNM), Editors: Ewa Chylinski/Mahulena Hofmannová power sharing arrangements and examples of good practice in minority governance. The present Handbook concerns the other Council of Europe convention dealing with minorities: the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (ECRML). The ECRML represents the European legal frame of reference for the The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility protection and promotion of languages used by persons belonging to traditional minorities. of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the ECMI. Regrettably, the importance of the ECRML is not reflected by the number of ratifications. While the FCNM has 39 States Parties, the ECRML has so far been ratified by 25 member States of the Council of Europe and signed by Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation a further eight member States. -

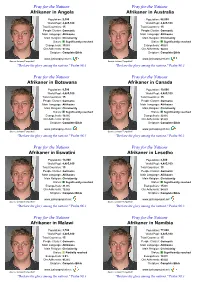

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afrikaner in Angola Afrikaner in Australia Population: 2,300 Population: 68,000 World Popl: 4,485,100 World Popl: 4,485,100 Total Countries: 15 Total Countries: 15 People Cluster: Germanic People Cluster: Germanic Main Language: Afrikaans Main Language: Afrikaans Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Christianity Status: Significantly reached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 35.0% Evangelicals: 45.0% Chr Adherents: 97.0% Chr Adherents: 94.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Johann Tempelhoff Source: Johann Tempelhoff "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afrikaner in Botswana Afrikaner in Canada Population: 9,500 Population: 10,000 World Popl: 4,485,100 World Popl: 4,485,100 Total Countries: 15 Total Countries: 15 People Cluster: Germanic People Cluster: Germanic Main Language: Afrikaans Main Language: Afrikaans Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Christianity Status: Significantly reached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 18.0% Evangelicals: 22.0% Chr Adherents: 97.0% Chr Adherents: 91.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Johann Tempelhoff Source: Johann Tempelhoff "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afrikaner in Eswatini -

Multilingualism in Strasbourg LUCIDE City Report

Multilingualism in Strasbourg LUCIDE city report LA OPE NG R UA U G E E R S O I F N Y U T R I B S A R N E V I C D O LUCIDE M D M N A U N N I O T I I T E A S R I N G E T E LA OP NG R UA U G E E R S O I F N Y U T R I B S A R N E V I C D O LUCIDE M D M N By Christine Hélot, Eloise Caporal Ebersold, A U N N I O T I I T E A S R I N G T E Andrea Young 1 Errata and updates, including broken links: www.urbanlanguages.eu/cityreports/errata Authors: Christine Hélot, Eloise Caporal Ebersold, Andrea Young University of Strasbourg, France © LUCIDE Project and LSE 2015 All images © University of Strasbourg unless otherwise stated Design by LSE Design Unit Published by: LSE Academic Publishing This report may be used or quoted for non-commercial reasons so long as both the LUCIDE consortium and the EC Lifelong Learning Program funding are acknowledged. www.urbanlanguages.eu www.facebook.com/urbanlanguages @urbanlanguages This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ISBN: 978-1-909890-25-1 This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the author(s), and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. -

THE SHORT OBLIGATORY PRAYER in 391 LANGUAGES, DIALECTS OR SCRIPTS BAHA'i BIBLIOGRAPHY 496 the Bahai WORLD 497 7

THE SHORT OBLIGATORY PRAYER IN 391 LANGUAGES, DIALECTS OR SCRIPTS BAHA'I BIBLIOGRAPHY 496 THE BAHAi WORLD 497 7. THE SHORT OBLIGATORY PRAYER Where identification in terms of this standard reference has not yet been completed, the nomenclature reported to the Worid Centre by the National Spiritual Assembly IN 391 LANGUAGES, DIALECTS OR SCRIPTS responsible for the accomplishment has been used, and such translations are indicated by a dagger. An asterisk denotes an improved translation made available for this volume in a language which has appeared in earlier volumes. The major countries, islands or territories where the languages are spoken are shown in italics; where no such entry is given, the places where the language is spoken are so numerous and so widely scattered that to Ust them would be unwieldy: many of these languages are found worldwide. Totals for each continent are: Africa, 129; the Americas, 89; Asia, 90; Australasia and the Pacific Islands, 31; Europe, 49; Invented languages, 2; Braille, 1. The total number of translations and transUterations is 391. A.AFRICA * Denotes revised translations. t Efforts to obtain exact identification continue. a ADANGME (Ghana) Otumfoo, medi hia buroburo na Woye odefoo. o Oo Tsaatse Mawu i yeo he odase kaa O bo mi Onyame foforo biara nni ho ka Wo ho, ohaw kone ma le Mo ne ma ja Mo. Pio hu i nge he mu Boafoo, Wo na wote Wo ho ne W'ase. odase yee kaa i be he wami ko; Moji he wamitse, ƒ bear witness, O my God, that Thou hast created me AKAN: Fante dialect (Ghana) to know Thee and to worship Thee. -

Untranslatables Translingual Dialogue

UNTRANSLATABLES – A GUIDE To – TRANSLINGUAL DIALOGUE 2 UNTRANSLATABLES, A GUIDE TO TRANSLINGUAL DIALOGUE AN INTRODUCTION 3 Dear reader, EU because of the economical and political climate in their own countries. By Europe we do not mean the EU, or Europe as a continent, or a historical With this book, we want to propose to you an adoption. An adoption of and cultural paradigm. We take the liberty of a subjective interpretation of thirty-three different words from various languages spoken in Europe a “Europe” that we recognise as a very alive entity and much more complex that are easy to pronounce and recognize, and that carry the potential to than the above segregating definitions. Therefore our untranslatable words become both real and immaterial ambassadors of “translingual” dialogue. include Arabic and Japanese as part of a Europe that serves better our By accepting this word from the source, untreated, with its own pronun- purpose and concept of an organism that is rich and alive and constantly ciation, a real cultural transfer takes place. The symbolic value of this is evolving. enormous; accepting this word in your daily vocabulary means: Without going deep into the political problems that language-protec- I choose to “absorb” one – historical, semantic, emotional – element tionism brings with it, but without neglecting them, we want to acknowl- from your culture into mine, since this element emblemizes an entire edge the differences between the various communities living in Europe, world, brings with it an idea for which there is simply no word in my lan- and promote an interchange between them, understanding untranslatable guage.