View of Methodology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests

THE POSITION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE MANAGEMENT OF TROPICAL FORESTS Gerard A. Persoon Tessa Minter Barbara Slee Clara van der Hammen Tropenbos International Wageningen, the Netherlands 2004 Gerard A. Persoon, Tessa Minter, Barbara Slee and Clara van der Hammen The Position of Indigenous Peoples in the Management of Tropical Forests (Tropenbos Series 23) Cover: Baduy (West-Java) planting rice ISBN 90-5113-073-2 ISSN 1383-6811 © 2004 Tropenbos International The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Tropenbos International. No part of this publication, apart from bibliographic data and brief quotations in critical reviews, may be reproduced, re-recorded or published in any form including print photocopy, microfilm, and electromagnetic record without prior written permission. Photos: Gerard A. Persoon (cover and Chapters 1, 2, 3, 4 and 7), Carlos Rodríguez and Clara van der Hammen (Chapter 5) and Barbara Slee (Chapter 6) Layout: Blanca Méndez CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 1. INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND NATURAL RESOURCE 3 MANAGEMENT IN INTERNATIONAL POLICY GUIDELINES 1.1 The International Labour Organization 3 1.1.1 Definitions 4 1.1.2 Indigenous peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 5 management 1.1.3 Resettlement 5 1.1.4 Free and prior informed consent 5 1.2 World Bank 6 1.2.1 Definitions 7 1.2.2 Indigenous Peoples’ position in relation to natural resource 7 management 1.2.3 Indigenous Peoples’ Development Plan and resettlement 8 1.3 UN Draft Declaration on the -

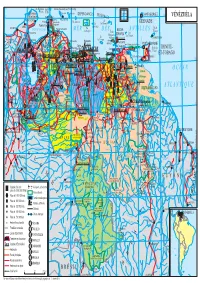

The State of Venezuela's Forests

ArtePortada 25/06/2002 09:20 pm Page 1 GLOBAL FOREST WATCH (GFW) WORLD RESOURCES INSTITUTE (WRI) The State of Venezuela’s Forests ACOANA UNEG A Case Study of the Guayana Region PROVITA FUDENA FUNDACIÓN POLAR GLOBAL FOREST WATCH GLOBAL FOREST WATCH • A Case Study of the Guayana Region The State of Venezuela’s Forests. Forests. The State of Venezuela’s Págs i-xvi 25/06/2002 02:09 pm Page i The State of Venezuela’s Forests A Case Study of the Guayana Region A Global Forest Watch Report prepared by: Mariapía Bevilacqua, Lya Cárdenas, Ana Liz Flores, Lionel Hernández, Erick Lares B., Alexander Mansutti R., Marta Miranda, José Ochoa G., Militza Rodríguez, and Elizabeth Selig Págs i-xvi 25/06/2002 02:09 pm Page ii AUTHORS: Presentation Forest Cover and Protected Areas: Each World Resources Institute Mariapía Bevilacqua (ACOANA) report represents a timely, scholarly and Marta Miranda (WRI) treatment of a subject of public con- Wildlife: cern. WRI takes responsibility for José Ochoa G. (ACOANA/WCS) choosing the study topics and guar- anteeing its authors and researchers Man has become increasingly aware of the absolute need to preserve nature, and to respect biodiver- Non-Timber Forest Products: freedom of inquiry. It also solicits Lya Cárdenas and responds to the guidance of sity as the only way to assure permanence of life on Earth. Thus, it is urgent not only to study animal Logging: advisory panels and expert review- and plant species, and ecosystems, but also the inner harmony by which they are linked. Lionel Hernández (UNEG) ers. -

Piaroa Shamanic Ethics and Ethos: Living by the Law and the Good Life of Tranquillity

International Journal of Latin American Religions (2018) 2:315–333 https://doi.org/10.1007/s41603-018-0059-0 Piaroa Shamanic Ethics and Ethos: Living by the Law and the Good Life of Tranquillity Robin Rodd1 Received: 18 July 2018 /Accepted: 7 October 2018 /Published online: 15 October 2018 # Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 Abstract The Amazonian cosmos is a battlefield where beauty is possible but violent chaos rules. As a result, the Piaroa world is characterised by an ongoing battle between shamans who uphold, on behalf of all Piaroa, the ideal of ethical living, and forces of chaos and destruction, epitomised by malevolent spirits (märi) and dangerous sorcerers. This essay draws on ethnographic research involving shamanic apprenticeship conducted between 1999 and 2002 to explore the ethics of Piaroa shamanic practice. Given the ambivalent nature of the Amazonian shaman as healer and sorcerer, what constitutes ethical shamanic practice? How is good defined relative to the potential for social and self-harm? I argue that the Piaroa notions of ‘living by the law’ and ‘the good life of tranquillity’ amount to a theory of shamanic ethics and an ethos in the sense of a culturally entrained system of moral and emotional sensibilities. This ethos turns on the importance of guiding pro-social, cooperative and peaceful behaviour in the context of a cosmos marked by violent chaos. Shamanic ethics also pivots around the ever-present possibility that visionary power dissolves into self- and social destruction. Ethical shamanic practice is contingent on shamans turning their own mastery of the social ecology of emotions into a communitarian reality. -

Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the Pan-Amazon Region

OAS/Ser.L/V/II. Doc. 176 29 September 2019 Original: Spanish INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Situation of Human Rights of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples of the Pan-Amazon Region 2019 iachr.org OAS Cataloging-in-Publication Data Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Situation of human rights of the indigenous and tribal peoples of the Pan-Amazon region : Approved by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on September 29, 2019. p. ; cm. (OAS. Official records ; OEA/Ser.L/V/II) ISBN 978-0-8270-6931-2 1. Indigenous peoples--Civil rights--Amazon River Region. 2. Indigenous peoples-- Legal status, laws, etc.--Amazon River Region. 3. Human rights--Amazon River Region. I. Title. II. Series. OEA/Ser.L/V/II. Doc.176/19 INTER-AMERICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Members Esmeralda Arosemena de Troitiño Joel Hernández García Antonia Urrejola Margarette May Macaulay Francisco José Eguiguren Praeli Luis Ernesto Vargas Silva Flávia Piovesan Executive Secretary Paulo Abrão Assistant Executive Secretary for Monitoring, Promotion and Technical Cooperation María Claudia Pulido Assistant Executive Secretary for the Case, Petition and Precautionary Measure System Marisol Blanchard a.i. Chief of Staff of the Executive Secretariat of the IACHR Fernanda Dos Anjos In collaboration with: Soledad García Muñoz, Special Rapporteurship on Economic, Social, Cultural, and Environmental Rights (ESCER) Approved by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on September 29, 2019 INDEX EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11 INTRODUCTION 19 CHAPTER 1 | INTER-AMERICAN STANDARDS ON INDIGENOUS AND TRIBAL PEOPLES APPLICABLE TO THE PAN-AMAZON REGION 27 A. Inter-American Standards Applicable to Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in the Pan-Amazon Region 29 1. -

Fact Sheet UNHCR Venezuela

FACT SHEET Venezuela March 2019 The country was hit by a massive nation-wide blackout on 7 March which lasted five days and was followed by recurrent long power outages throughout the rest of the month. The blackout brought Venezuela to a standstill and interrupted already unreliable water, telecommunications, electronic payment and fuel services. Particularly hit were the western states of Apure, Táchira and Zulia –where most of UNHCR’s prioritised communities lie- and Maracaibo, the country’s second largest city, was wrought by widespread looting. The outage seriously affected operational capacity and morale in field offices and the living conditions of people of concern to UNHCR. The borders with Colombia and Brazil remained closed throughout the month, forcing people in transit to use increasingly risky and expensive informal crossing routes and impacting negatively on the livelihoods of border communities that have been traditionally dependent on cross-border commuting. The political power struggle continued, with opposition leader Juan Guaido’ making a triumphal return to the country on 1 March and exploiting the blackout to step up mobilisation against President Nicolas Maduro. The government blamed the blackouts on sabotage by the opposition and technological attacks by the United States, while the opposition blamed it on government ineptitude and corruption. The economy of Venezuela ground to a halt, schools and offices remained closed for most of the month and shops only accepted cash, which has been traditionally scarce. The Bolivar has been gradually supplanted by the Colombian peso and the Brazilian real at the borders and by the US dollar in Caracas. -

Music, Plants, and Medicine: Lamista Shamanism in the Age of Internationalization

MUSIC, PLANTS, AND MEDICINE: LAMISTA SHAMANISM IN THE AGE OF INTERNATIONALIZATION By CHRISTINA MARIA CALLICOTT A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Christina Maria Callicott In honor of don Leovijildo Ríos Torrejón, who prayed hard over me for three nights and doused me with cigarette smoke, scented waters, and cologne. In so doing, his faith overcame my skepticism and enabled me to salvage my year of fieldwork that, up to that point, had gone terribly awry. In 2019, don Leo vanished into the ethers, never to be seen again. This work is also dedicated to the wonderful women, both Kichwa and mestiza, who took such good care of me during my time in Peru: Maya Arce, Chabu Mendoza, Mama Rosario Tuanama Amasifuen, and my dear friend Neci. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the kindness and generosity of the Kichwa people of San Martín. I am especially indebted to the people of Yaku Shutuna Rumi, who welcomed me into their homes and lives with great love and affection, and who gave me the run of their community during my stay in El Dorado. I am also grateful to the people of Wayku, who entertained my unannounced visits and inscrutable questioning, as well as the people of the many other communities who so graciously received me and my colleagues for our brief visits. I have received support and encouragement from a great many people during the eight years that it has taken to complete this project. -

AMAZONAS PUERTO AYACUCHO CENTRO MEDICO AMAZONAS Av. Rómulo Gallegos, Puerto Ayacucho (0248) 5213883 / 4445 / 2491 ANZOATEGUI AN

ESTADO LOCALIDAD PROVEEDOR DE SALUD DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONOS AMAZONAS PUERTO AYACUCHO CENTRO MEDICO AMAZONAS Av. Rómulo Gallegos, Puerto Ayacucho (0248) 5213883 / 4445 / 2491 ANZOATEGUI ANACO GRUPO MEDICO ORIENTE (Electivas) Calle Colombia, Cruce C/C La Industria. (0282) 4002053 / 4222476 / 4255790 ANZOATEGUI BARCELONA CENTRO MEDICO ZAMBRANO Av. Caracas, Frente Al Hotel Oliviana (0281) 2701311 / 2763550 / 2762611 ANZOATEGUI BARCELONA UNIDAD CLINICA DE ESPECIALIDADES ORIENTE Av. Country Club Con Calle Maturín N 89 (0281) 2740423 ANZOATEGUI EL TIGRE CENTRO MEDICO MAZZARRI-REY Calle 20. Sur No. 8. Al Lado De Intercable. (0283) 2410467 ANZOATEGUI EL TIGRE CLINICA SANTA ROSA C.A Av. Francisco de Miranda Nro. 223 El Tigre Edo. Anzoategui (0283-5005100 ) Av Winston churchill local Nro S/N Sector Pueblo Nuevo Sur El ANZOATEGUI EL TIGRE CENTRO QUIRURGICO WINSTON CHURCHILL C.A. (0283)2413379 Tigre Anzoategui. ANZOATEGUI PUERTO LA CRUZ CENTRO CLINICO SANTA ANA Av. Principal, Urb. Caribe, N° 43 Pto. La Cruz. (0281) 5009262 / 5009222 An cinco de julio cruce con calle Arismendi N 40 Sector centro ANZOATEGUI PUERTO LA CRUZ POLICLINICA PUERTO LA CRUZ (0281) 2685332/2675904 Puerto la Cruz ANZOATEGUI PUERTO LA CRUZ CENTRO DE ESPECIALIDADES MEDICAS VIRGEN DEL VALLE Final Calle 1, Urb. Chuparin. (0281) 2685301 7 2697320 / 9835 9 Av Intercomunal Jorge Rodríguez, Lechería 6016, ANZOATEGUI LECHERIA CENTRO MEDICO TOTAL (0281) 2657311 Anzoátegui Av. Principal De Lecherías, N° 55, Fte. Al Centro Médico ANZOATEGUI LECHERIA UNIDAD MEDICA OFTALMOLOGICA DE LECHERIA (0281) 2868777 / 2493 Anzoátegui, Lecherías APURE SAN FERNANDO DE APURE CENTRO MEDICO DEL SUR Av. Revolución, Edif. Centro Médico Del Sur (0247)341.5262 Calle Comercio, N° 65-29 Y 65-28, Entre Bermúdez Y ARAGUA CAGUA POLICLINICA CENTRO (0244) 34478005 Pichincha ARAGUA CAGUA UNIDAD MEDICA QUIRURGICA DRA. -

A Comparative Analysis of Piaroa and Cuiva Yopo Use Robin Rodd Ph.D

This article was downloaded by: [JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY] On: 01 May 2013, At: 22:43 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Journal of Psychoactive Drugs Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujpd20 Yopo, Ethnicity and Social Change: A Comparative Analysis of Piaroa and Cuiva Yopo Use Robin Rodd Ph.D. a & Arelis Sumabila Ph.D. b a School of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia b Anthropology Department, Macquarie University, North Ryde, Australia Published online: 08 Apr 2011. To cite this article: Robin Rodd Ph.D. & Arelis Sumabila Ph.D. (2011): Yopo, Ethnicity and Social Change: A Comparative Analysis of Piaroa and Cuiva Yopo Use, Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43:1, 36-45 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2011.566499 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Colombia Curriculum Guide 090916.Pmd

National Geographic describes Colombia as South America’s sleeping giant, awakening to its vast potential. “The Door of the Americas” offers guests a cornucopia of natural wonders alongside sleepy, authentic villages and vibrant, progressive cities. The diverse, tropical country of Colombia is a place where tourism is now booming, and the turmoil and unrest of guerrilla conflict are yesterday’s news. Today tourists find themselves in what seems to be the best of all destinations... panoramic beaches, jungle hiking trails, breathtaking volcanoes and waterfalls, deserts, adventure sports, unmatched flora and fauna, centuries old indigenous cultures, and an almost daily celebration of food, fashion and festivals. The warm temperatures of the lowlands contrast with the cool of the highlands and the freezing nights of the upper Andes. Colombia is as rich in both nature and natural resources as any place in the world. It passionately protects its unmatched wildlife, while warmly sharing its coffee, its emeralds, and its happiness with the world. It boasts as many animal species as any country on Earth, hosting more than 1,889 species of birds, 763 species of amphibians, 479 species of mammals, 571 species of reptiles, 3,533 species of fish, and a mind-blowing 30,436 species of plants. Yet Colombia is so much more than jaguars, sombreros and the legend of El Dorado. A TIME magazine cover story properly noted “The Colombian Comeback” by explaining its rise “from nearly failed state to emerging global player in less than a decade.” It is respected as “The Fashion Capital of Latin America,” “The Salsa Capital of the World,” the host of the world’s largest theater festival and the home of the world’s second largest carnival. -

Estratificación Del Riesgo De Dengue En La Ciudad De Puerto Ayacucho, Estado Amazonas, Venezuela

Revista del Instituto Nacional de Higiene “Rafael Rangel”, 2014; 45 (1) Estratificación del riesgo de dengue en la ciudad de Puerto Ayacucho, estado Amazonas, Venezuela. Período 1995-2010. Dengue fever risk stratification in Puerto Ayacucho City, Amazonas State, Venezuela. 1995-2010 period. NATHALIA E CARDONA CH1, MARIA C DUARTE R1, LUISA M DELGADO M2, KENIA DEL V GONZÁLEZ B3, DAISY M GARCÍA O1, MILIAN C PACHECO T1, CARLOS BOTTO A1 RESUMEN ABSTRACT El control del Aedes aegypti (vector principal del Dengue), Control of Aedes aegypti is difficult to perform due to the se dificulta por la extensión y heterogeneidad de los ba- extent and variety of neighborhoods where the breeding rrios donde se encuentran los criaderos, la carencia de grounds are found, the lack of permanent access to public acceso permanente a servicios públicos y por la ausencia services, and to the absence of a strict and constant epi- de vigilancia epidemiológica estricta y constante. Se regis- demiological surveillance. 2,603 confirmed dengue cases traron 2.603 casos de dengue confirmados por IgM-den- (IgM-dengue) were recorded during the 1995-2010 period. gue, durante el período 1995-2010. El estudio se realizó This study was carried out in Puerto Ayacucho, main city en Puerto Ayacucho, capital del estado Amazonas con of Amazonas State, Venezuela, with 98,824 inhabitants. 98.824 habitantes. Los casos confirmados se agruparon Confirmed cases of individuals affected were grouped de acuerdo con la localización de su residencia. La infor- according to the location of their residence. Information mación se representó espacialmente para analizar los pa- is spatially represented to analyze space-time patterns trones espacio-temporales del dengue, estableciéndose of dengue, establishing a stratification of the city. -

O C É a N a T L a N T I Q

74° 72°Îles Los Monjes Aruba 70° Antilles Néerlandaises (PAYS-BAS) 66° 64° 62° 60° (VÉN.) Péninsule (P.-B.) Curaçao Bonaire É Île de Aves D PENDANCES FÉ É SAINT-GEORGES 12° VÉNÉZUÉLA 12° de la Guajira Pueblo Nuevo D RAL ES 15°30 63°30 PUERTO LÓPEZ Adicora WILLEMSTAD Île Amuay PPéninsuleéninsule de Îles Las Aves GRENADE ParaguanParaguanáá Île La Blanquilla 58° URIBIA Punto Fijo La Orchila RIOHACHA Golfe du Venezuela Puerto Cumarebo Îles Île de M E R Los Roques D E S NU E V A A N T I L L E S Tobago Paraguaipoa Île de Îles Coro Margarita ESPARTA Los Testigos Sabaneta Île Altagracia n SCARBOROUGH Á La Asunción o Pic Christophe IJ f La Tortuga g R San Ra ael La Cruz Boca a v r Colomb E Chichiri iche Maiquetía m Porla ar D P de Taratara La Guaira de Pozo PORT D'ESPAGNE 5775 u E Altagraraciacia Churuguara Péninsule de Paria Ó Catia Carúpano d D FALC N s Puerto e Île de la TRINITÉ- la Mar Araya h CARACAS c Maracaibo SantSantaa Rita Morón Cabello Cariaco Güiria u ARIMA Trinité VALLEDUPAR LARA San Felipe o 6 H Cumaná B A Maracay iguerote SUCRE ET-TOBAGO R 1787 vers SANTA MARTA Rosario Cabimas Petare R Barquisimeto 5 Golfe de Paria SAN FERNANDO E I Ciudad Ojeda Barcelona Caripito Bo 10° S Machiques Carora 7 Los Teques uc POINT FORTIN Lac 4 8 Quiriquire he d 3750 Quibor Yaritagua Turmero Puerto u Serpent Barranquitas Mene Grande Cabudare Valencia Clarines Maturín Pedernales de Altagracia la Cruz 3130 San Juan O C É A N Araure de Orituco Aragua de Punta de Mata a Delta de Maracaibo San Carlos Anaco ip ZULIA Trujillo 3652 de los Morros Barcelona Aguasay Guan Valera Acarigua Zaraza MONAGAS l'Orl'Orénoqueénoque é El Sombrero Tucupido Cantaura San Carlos 2 Turén COJEDES Puerto Tucupita del Zulia Boconó Guanare El Baúl Valle de El Salto Amador 4000 o Calabozo Calderas a la Pascua A T L A N T I Q U E EL BANCO MÉRIDA 3 P Á El Tigre DELTA AMAMACACURO Casigua A are G U RIM C O a uan á Barrancas 4762 D G Pariag n n Edijo I o a e c R n l El Vigía i Espino É Barinas Guanarito r PARC NAT. -

Appendix B: Places

Appendix B: Place codes The following list provides state-specific codes for all place variables. This means that, in most cases, the meaning of the place code is dependent on the corresponding state code. The list contains the sections: generic codes, places in the countries of study (Uruguay, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Perú, and Venezuela), U.S. places, and, other international places. Generic codes For all geographical variables, there exist a set of commonly used codes: 0000 Concealed code (to protect confidentiality) 8888 Not applicable 9999 Unknown / missing U.S.- specific generic code: 7777 Existing location, but outside of established municipio/MSA/city. Note: The Generic place codes are the only geo-codes that are not state-specific. Uruguay (287) Places at the Department level have a 4-number code; if the city was located at a smaller geographical region, the code will have a 1- or a 2-number code. Cities Departments 1 Montevideo 1901 Artigas 2 Punta del Este 1902 Canelones 3 Minas 1903 Cerro Largo 4 Punta del Diablo 1904 Colonia 5 Las Piedras 1905 Durazno 6 Castillos 1906 Flores 7 Pando 1907 Florida 8 Paso de los Toros 1908 Lavalleja 9 Santa Lucía 1909 Maldonado 10 Barros Blancos 1910 Montevideo 1911 Paysandú 1912 Río Negro 1913 Rivera 1914 Rocha 1915 Salto 1916 San José 1917 Soriano 1918 Tacuarembo 1919 Treinta yTres LAMP UY4 - B1 - August 2020 Cuba (237) Places at the Provincia level have a 4-number code; if the city was located at a smaller geographical region, the code will have a 1- or a 2-number code.