Comparative Costs of British Cross-Channel Airlines, 1918-1924 Robin Higham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imperial Airways

IMPERIAL AIRWAYS 1 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW.XV Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 2 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. G-ADSR, Ensign Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 3 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW15 Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways, air to air, 1932. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 4 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBLF, Imperial Airways, 1929. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 5 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, 1937. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 6 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atlanta, G-ABTL, Astraea Imperial Airways, Royal Mail GR. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 7 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atalanta, G-ABTK, Athena, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 8 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Argosy, G-EBLO, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 9 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 10 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 11 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBOZ, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 12 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW 27 Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 13 AVRO. 652, G-ACRM, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 14 AVRO. 652, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 15 AVRO. Avalon, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 16 BENNETT, D. C. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

TEED!* * Find It Lower? We Will Match It

Spring 2018 BRINGING HISTORY TO LIFE Kits & Accessories NEW! USS HAWAII CB-3 PG.45 PANTHER See page 3 Books & Magazines for details on this exciting new kit. NEW! PANTHER TANK IN ACTION PG. 3 Tools & Paint EVERYTHING YOU NEED FOR MODELMAKING PGS. 58-61 Model Displays OVER 75 NEW KITS, BOOKS MARSTON MAT pg. 24 LOWEST PRICE GUARANTEED!* & ACCESSORIES INSIDE! * * See back cover for full details. Order Today at WWW.SQUADRON.COM or call 1-877-414-0434 Dear Friends, Now that we’ve launched into daylight savings time, I have cleared off my workbench to start several new projects with the additional evening light. I feel really motivated at this moment and with all the great new products we have loaded into this catalog, I think it is going to be a productive spring. As the seasons change, now is the perfect time to start something new; especially for those who have been considering giving the hobby a try, but haven’t mustered the energy to give it a shot. For this reason, be sure to check out pp. 34 - our new feature page especially for people wanting to give the hobby a try. With products for all ages, a great first experience is a sure thing! The big news on the new kit front is the Panther Tank. In conjunction with the new Takom (pp. 3 & 27) kits, Squadron Signal Publications has introduced a great book about this fascinating piece of German armor (SS12059 - pp. 3). Author David Doyle guides you through the incredible history of the WWII German Panzerkampfwagen V Panther. -

Brooklands Aerodrome & Motor

BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY (June 2017) Radley House Partnership BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS CONTENTS Aerodrome Road 2 The 1907 BARC Clubhouse 8 Bellman Hangar 22 The Brooklands Memorial (1957) 33 Brooklands Motoring History 36 Byfleet Banking 41 The Campbell Road Circuit (1937) 46 Extreme Weather 50 The Finishing Straight 54 Fuel Facilities 65 Members’ Hill, Test Hill & Restaurant Buildings 69 Members’ Hill Grandstands 77 The Railway Straight Hangar 79 The Stratosphere Chamber & Supersonic Wind Tunnel 82 Vickers Aviation Ltd 86 Cover Photographs: Aerial photographs over Brooklands (16 July 2014) © reproduced courtesy of Ian Haskell Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY Radley House Partnership Timelines: June 2017 Page 1 of 93 ‘AERODROME ROAD’ AT BROOKLANDS, SURREY 1904: Britain’s first tarmacadam road constructed (location?) – recorded by TRL Ltd’s Library (ref. Francis, 2001/2). June 1907: Brooklands Motor Circuit completed for Hugh & Ethel Locke King and first opened; construction work included diverting the River Wey in two places. Although the secondary use of the site as an aerodrome was not yet anticipated, the Brooklands Automobile Racing Club soon encouraged flying there by offering a £2,500 prize for the first powered flight around the Circuit by the end of 1907! February 1908: Colonel Lindsay Lloyd (Brooklands’ new Clerk of the Course) elected a member of the Aero Club of Great Britain. 29/06/1908: First known air photos of Brooklands taken from a hot air balloon – no sign of any existing route along the future Aerodrome Road (A/R) and the River Wey still meandered across the road’s future path although a footbridge(?) carried a rough track to Hollicks Farm (ref. -

Science Museum Library and Archives Science Museum at Wroughton Hackpen Lane Wroughton Swindon SN4 9NS

Science Museum Library and Archives Science Museum at Wroughton Hackpen Lane Wroughton Swindon SN4 9NS Telephone: 01793 846222 Email: [email protected] NAP Collection of miscellaneous records of the engineering company D. Napier & Son Compiled by Robert Sharp NAP Following a suggestion from the president of the Veteran Car Club in 1962, much valuable historical material of D Napier & Son Ltd was donated to the Museum's Transport Department in 1963-64. Additional material was donated when the company was taken over by the General Electric Company in late 1973. This material was transferred to the Archives Collection in 1989. NAP 1/38 to 1/43 comprises six historical articles on the Napier company while NAP 4/2 includes a review Men and Machines: a history of D Napier & Son, Engineers Ltd 1808-1958 * by C H Wilson & W Reader (1958). Other historical background material is in NAP 5/3 and 5/4. Contents 1 1902-1958 Advertising and publicity booklets, brochures, press articles etc 2 - Instruction books 3 1929 Napier Aero Engines (booklet) 4 1955-1959 Periodicals 5 1921-1961 Napier family, personal history 6 1906-1936 Trade advertisements 7 1942-1943 Ministry of Aircraft Production 8 - Lists of photographs 9 1905-1931 Miscellaneous 10 1933-1947 John Cobb 11 1927-1932 Malcolm Campbell 12 1918 Silk calendar 13 1899-195- Photographs 14 1922-1930 Testimonials 15 1900-1904 Design notebooks 16 1949-1961 Engineering notebooks 17 1899-1955 Drawings 18 1913-1931 Photograph albums 1 Advertising and publicity booklets, brochures press articles etc. 1/1 (1907) Napier 1/2 (1923) Napier. -

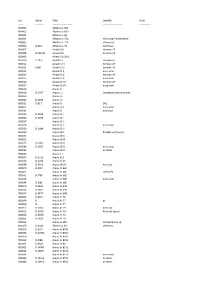

Name of Plan Wing Span Details Sour Ce Area Price

WING SOUR NAME OF PLAN DETAILS AREA PRICE AMA POND RC FF CL OT SCALE GAS RUBBER ELECTRIC OTHER GLIDER 3 VIEW ENGINE RED. OT SPAN CE V 1 BUZZ BOMB NIGEL HAWES 40 12 $15 33689 77E7 X X X DOODLEBUG JACK VARTANIAN 1935 V B 2 96 18 $21 25536 48G1 X X X V B 2 $0 35127 RD552 X V B 41A $0 35128 RD553 X G BUSEK 1941, CZECHOSLOVAKIA V B 41A STRIBRNA 52 7 $9 33207 7E3 X X X G BUSEK 1941, CZECHOSLOVAKIA V B 43 BETA MINOR 52 12 $15 32967 57E5 X X X G BUSEK, CZECHOSLOVAKIA 1941 V B 45 KONDOR 57 12 $15 25076 45A5 X X V B 48 $0 35129 RD554 X G BUSEK, CZECHOSLOVAKIA 1941 V B 48 OSTRIZ 50 10 $13 25079 45A6 X X V B 601 $0 35130 RD555 X G BUSEK, CZECKOSLOVAKIA V B 602 REJNOK 50 12 $15 29605 72E3 X X JIROTKA, POLAND V J 6 44 6 $8 26680 57E7 X X VILLAGE MODEL SHOP 1940 V M S GAMMA 44 4 $5 23535 32G5 X X X V M S GAMMA $0 35133 RD558 X FLYING MODELS 2/55, PALANEK V T O 14 3 $4 30087 76F3 X X X JASCO 1937 YEARBOOK, LOWE V TAIL SWALLOW 84 22 $24 25540 48G3 X X X BERKELEY KIT PLAN V-16 13 4 $5 20801 10F3 X X NATIONAL GLIDER 1/32 VACUPLANE MODEL 9 20 $22 31193 81G1 X X AEROMODELLER PLAN, MARCH VAE VICTIS 42 1988 3 $4 14239 X X EAGLE MODEL AIRCRAFT CO. -

B&W Real.Xlsx

NO REGN TYPE OWNER YEAR ‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ X00001 Albatros L‐68C X00002 Albatros L‐68D X00003 Albatros L‐69 X00004 Albatros L‐72C Hamburg Fremdenblatt X00005 Albatros L‐72C striped c/s X00006 D‐961 Albatros L‐73 Lufthansa X00007 Aviatik B.II German AF X00008 B.558/15 Aviatik B.II German AF X00009 Aviatik PG.20/2 X00010 C.1952 Aviatik C.I German AF X00011 Aviatik C.III German AF X00012 6306 Aviatik C.IX German AF X00013 Aviatik D.II nose view X00014 Aviatik D.III German AF X00015 Aviatik D.III nose view X00016 Aviatik D.VII German AF X00017 Aviatik D.VII nose view X00018 Arado J.1 X00019 D‐1707 Arado L.1 Ostseebad Warnemunde X00020 Arado L.II X00021 D‐1874 Arado L.II X00022 D‐817 Arado S.I DVL X00023 Arado S.IA nose view X00024 Arado S.I modified X00025 D‐1204 Arado SC.I X00026 D‐1192 Arado SC.I X00027 Arado SC.Ii X00028 Arado SC.II nose view X00029 D‐1984 Arado SC.II X00030 Arado SD.1 floatplane @ (poor) X00031 Arado SD.II X00032 Arado SD.III X00033 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I X00034 D‐1905 Arado SSD.I nose view X00035 Arado SSD.I on floats X00036 Arado V.I X00037 D‐1412 Arado W.2 X00038 D‐2994 Arado Ar.66 X00039 D‐IGAX Arado AR.66 Air to Air X00040 D‐IZOF Arado Ar.66C X00041 Arado Ar.68E Luftwaffe X00042 D‐ITEP Arado Ar.68E X00043 Arado Ar.68E nose view X00044 D‐IKIN Arado Ar.68F X00045 D‐2822 Arado Ar.69A X00046 D‐2827 Arado Ar.69B X00047 D‐EPYT Arado Ar.69B X00048 D‐IRAS Arado Ar.76 X00049 D‐ Arado Ar.77 @ X00050 D‐ Arado Ar.77 X00051 D‐EDCG Arado Ar.79 Air to Air X00052 D‐EHCR -

Compiled by Lincoln Ross Model Name/Article Title/Etc. Author

compiled by Lincoln Ross currently, issues 82 (Jan 1983) thru 293 (Jan 2017), 296 (Jul, 2017) thru 300 (Mar/April 2018), also 1 (Nov. 1967), 2, 3, 36, 71 (Jan. 1980) and 82 (Jan 1982) I've tried to get all the major articles, all the three views, and all the plans. However, this is a work in progress and I find that sometimes I miss things, or I may be inconsistent about what makes the cut and what doesn’t. If you found it somewhere else, you may find a more up to date version of this document in the Exotic and Special Interest/ Free Flight section in RCGroups.com. http://www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?t=1877075 Send corrections to lincolnr "at" rcn "dot" com. Also, if you contributed something, and I've got you listed as "anonymous", please let me know and I'll add your name. Loans or scans of the missing issues would be very much appreciated, although not strictly necessary. Before issue 71, I only have pdf files. Many thanks to Jim Zolbe for a number of scans and index entries. His contributions are shaded pale blue. In some cases, there are duplications that I've kept due to more information or what I thinkissue is a better entry date, issu usually e first of model name/article author/designe span no. two title/etc. r in. type comment 1 Lt. Phineas Nov 67 Club News Pinkham na note "c/o Dave Stott", introduces the newsletter 1 The first peanut scale contest, also 13 inch Nov 67 Peanut Scale GHQ na note rule announcement. -

An Interesting Point © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This Work Is Copyright

AN INTERESTING POINT © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Cover Image: ‘Flying Start’ by Norm Clifford - QinetiQ Pty Ltd National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Campbell-Wright, Steve, author. Title: An interesting point : a history of military aviation at Point Cook 1914-2014 / Steve Campbell-Wright. ISBN: 9781925062007 (paperback) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Aeronautics, Military--Victoria--Point Cook--History. Air pilots, Military--Victoria--Point Cook. Point Cook (Vic.)--History. Other. Authors/Contributors: Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. Dewey Number: 358.400994 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre F3-G, Department of Defence Telephone: + 61 2 6128 7041 PO Box 7932 Facsimile: + 61 2 6128 7053 CANBERRA BC 2610 Email: [email protected] AUSTRALIA Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower AN INTERESTING A History of Military Aviation at Point Cook 1914 – 2014 Steve Campbell-Wright ABOUT THE AUTHOR Steve Campbell-Wright has served in the Air Force for over 30 years. He holds a Masters degree in arts from the University of Melbourne and postgraduate qualifications in cultural heritage from Deakin University. -

Wing Span Details S O Price Ama Pond Rc Ff Cl O T Gas

RC SCALE ELECTRIC ENGINE NAME OF PLAN WING DETAILS SPRICE AMA POND FF CL O GAS RUBBER GLIDER 3 reduced SPAN O T V plan Pylon Racer/sport M X Supercat: 28 $9 00362 X flier. Aileron, elevator a C.control, E. BOWDEN, foam wing, r 1B4 X X BLUE DRAGON 96 $19 20030 X 1934 BUCCANEER B BERKELEY KIT 1C6 X X 48 $20 20053 X SPECIAL PLAN, 1940 (INSTRUCTIONS DENNY 1G7 X X DENNYPLANE JR. 72 $24 20103 X INDUSTRIES 1936 MODEL AIRPLANE 6B4 X COMMANDO 48 $13 20386 X NEWS 12/44, FLUGEHLING & MODELL 46C7 X WESPE 36 $7 25241 X TECHNIK 2/61, HAROLDFRIEDRICH DeBOLT 64G4 X X X BLITZKRIEG 60 $22 28724 X 1938 MODEL AIRCRAFT 66A3 X SKYVIKING 17 $4 28848 X 8/58, MALMSTROM AEROMODELLER 66A4 X DWARF 22 $3 28849 X PLANS 11/82, MODELHILLIARD AIRPLANE 67A5 X X TURNER SPECIAL* 42 $8 28965 X NEWS 5/36, AEROMODELLERTURNER 75F7 X TAMER LANE 28 $4 29959 X PLAN 8/79, FLUGCLARKSON & MODELL 77D7 X W I K 12 48 $7 30190 X TECHNIK 9/55, PERFORMANCEKLINGER 83A3 X SUN BIRD C 4 51 $18 30609 X KITS P T 16 1/2 38 $13 33800 X 91F7 X FLUG & MODELE X WE-GE 53 $15 50434 X TECHNIK, 4/92 COMET CLIPPER COMET KIT PLAN, 1D3 X X 72 $25 20063 X MK II, 3 SHEETS 1940 CLOUD CRUISER, MODEL AIRPLANE 1F5 X X 72 $29 20093 X 2 SHEETS NEWS, MOYER 7/37 AERONCA SPORT MODEL 13A2 X X 37 $13 21104 X PLANE CRAFTSMAN 1/40, YAKOVLEV Y A K 4 MODELOGRINZ AIRCRAFT 31E4 C C 50 $21 23357 C RECONNAISANCE 5/61, TAYLOR NORTH AMERICAN MODEL AIRPLANE 38F4 C C X 38 $20 24308 C F J 3 FURY NEWS 4/62, COLES BRISTOL 170 AMERICAN 49C6 C C 40 $13 25597 C FREIGHTER MODELER 1961 CANNUAL, & S MODEL LAUMER CO. -

Swansea Branch Chronicle 12

Issue 12 Spring 2016 Contents Transport 3 From the Editor The next train has gone ten minutes ago. Punch 4 Wheels in Wales Ian Smith If Rosa Parks had not refused to move to the back of the bus, you and I might never 7 Civil Aviation have heard of Dr. Martin John Ashley Luther King. Ramsey Clark 10 Wagons away Richard Hall 13 ‘Sketty Hall’ John Law 14 The Bus Museum Greg Freeman 16 The Mary Herberd Ralph Griffiths 18 Trolley Buses Roger Atkinson 20 Branch News 22 Book review 24 Programme On Sunday, I took a train, which didn't seem to want to go to Newcastle. J.B.Priestley Cover: The cover painting is an Imperial Airways poster from 1926, showing an Armstrong Whitworth Argosy on the tarmac at Croydon Airport. The famous tower with its radio aerials is in the background. From the Editor [email protected] A Traveller's tale Much to my surprise, I recently found myself giving a talk in the Coventry When not on the omnibus, it used to be considered Transport Museum . bad manners to smoke when driving with a lady… It was only on researching my subject that I ‘Permission must of course always be asked of the realised how transport and transport maps had so lady. It is scarcely ever refused, and it is almost affected my life. Lots of old books on the subject an exceptional thing to see a man driving without threw up some very interesting tips. a cigar between his teeth’. Here is one that you might have forgotten., The good old days. -

Newton's Lantern Slide Catalogue: Section 7 -- Industries And

1 r\:.- ‘ r : v i »V‘ » i |i.Jnai^P»i mmm • ,Vv^ - •• ? 3/ T^rtTwfiTrfT?? w- •• * Wm • :• * 5> KM^japft ifijjf* • ' ,-c -—»• ; /; tA-v^ »^ujr-*g**T> :- * ' ‘ * . * v, »/*>;•* 'fhtHiSU^ b y y ;ci>3 • . * »,. •. *. ,*t.* rr- jm. if v .ax' (j.* •i’K’ .’-l >••’•' "“tt* < c- .Ar S|l| i \ ..sc; #/ INDEX OF LANTERN SLIDES OF SECTION 7—INDUSTRIES AND MANUFACTURES. Page Page Page Aeroplanes 805-806 Engineering ... 812, 818, 825 Paper, Origin and Manufacture 829 Ancient and Modem Bridges 823 Engines 807, 808, 809, 817, 818 Portable Engines 818 Portland Cement' ... ... 834 >1 ft it Traffic... 822 Evolution of an Ironclad ... 814 „ Coins 831 Pottery Manufactures ... 828 Aquitania, R.M.S. 812 Gas Manufacture 832 Printing, Early, and Printers 829 History of Artillery, . Modem 814 Glass and Glass Making ... 828 ,, 829 Australian Great ... ... Production of the Rice Crop 839 Wines 841 Railways 819 ” Aviation 805-806 Production of “ The Times Handley-Page Aeroplane, Con- Newspaper 830 struction of 806 Beetroot Sugar ... 835,' 845 Herring Fishery 824 Railway Centenary Bicycles and Motor Cycles, 820 Hire of Slides 846 Construction and Sunbeam 821 ,, History and Manufacture of Biscuit Industry 832 Rolling Stock ... 819 , Pottery, and Porcelain 828 Rice Crop 839 Boot Making ... 835 „ of Printing 829 ,, Cultivation in the Philip- Boxes and Cabinets ... 847-848 How the Coin of the Realm is Bread Making 832 pines 840 made 831 Road Locomotives ... ... 817 Bread Making by Machinery 831 Brewing 836 Romance of Dyeing and Clean- ing Bridge, Saltash 809 Imperial Airways 805 834 Rope and ... Bridges, Ancient and Modem 823 Induction Coils, Construction Twine Making 836 Royal Victualling Yard ..