POLICE AVIATION a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

De Havilland Tiger Moth 47” Wing Span Plan

de Havilland Tiger Moth 47” Wing Span Plan The de Havilland DH 82 Tiger Moth is a 1930s biplane designed by Geoffrey de Havilland and was operated by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and others as a primary trainer. The Tiger Moth remained in service with the RAF until replaced by the de Havilland Chipmunk in 1952, when many of the surplus aircraft entered civil operation. Many other nations used the Tiger Moth in both military and civil applications, and it remains in widespread use as a recreational aircraft in many countries. It is still occasionally used as a primary training aircraft, particularly for those pilots wanting to gain experience before moving on to other tailwheel aircraft, although most Tiger Moths have a skid. Many are now employed by various companies offering trial lesson experiences. Those in private hands generally fly far fewer hours and tend to be kept in concours condition. The de Havilland Moth club founded 1975 is now a highly organized owners' association offering technical support and focus for Moth enthusiasts. de Havilland Tiger Moth 47” Wing Span Plan de Havilland Tiger Moth 47” Wing Span Plan Design and development The Tiger Moth trainer prototype was derived from the DH 60 de Havilland Gipsy Moth in response to Air Ministry specification 13/31 for an ab-initio training aircraft. The main change to the DH Moth series was necessitated by a desire to improve access to the front cockpit since the training requirement specified that the front seat occupant had to be able to escape easily, especially when wearing a parachute.[2] Access to the front cockpit of the Moth predecessors was restricted by the proximity of the aircraft's fuel tank directly above the front cockpit and the rear cabane struts for the upper wing. -

Airwork Limited

AN APPRECIATION The Council of the Royal Aeronautical Society wish to thank those Companies who, by their generous co-operation, have done so much to help in the production of the Journal ACCLES & POLLOCK LIMITED AIRWORK LIMITED _5£ f» g AIRWORK LIMITED AEROPLANE & MOTOR ALUMINIUM ALVIS LIMITED CASTINGS LTD. ALUMINIUM CASTINGS ^-^rr AIRCRAFT MATERIALS LIMITED ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY MOTORS LTD. STRUCTURAL MATERIALS ARMSTRONG SIDDELEY and COMPONENTS AIRSPEED LIMITED SIR W. G. ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH AIRCRAFT LTD. SIR W. G. ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH AIRCRAFT LIMITED AUSTER AIRCRAFT LIMITED BLACKBURN AIRCRAFT LTD. ^%N AUSTER Blackburn I AIRCRAFT I AUTOMOTIVE PRODUCTS COMPANY LTD. JAMES BOOTH & COMPANY LTD. (H1GH PRECISION! HYDRAULICS a;) I DURALUMIN LJOC kneed *(6>S'f*ir> tttaot • AVIMO LIMITED BOULTON PAUL AIRCRAFT L"TD. OPTICAL - MECHANICAL - ELECTRICAL INSTRUMENTS AERONAUTICAL EQUIPMENT BAKELITE LIMITED BRAKE LININGS LIMITED BAKELITE d> PLASTICS KEGD. TEAM MARKS ilMilNIICI1TIIH I BRAKE AND CLUTCH LININGS T. M. BIRKETT & SONS LTD. THE BRISTOL AEROPLANE CO., LTD. NON-FERROUS CASTINGS AND MACHINED PARTS HANLEY - - STAFFS THE BRITISH ALUMINIUM CO., LTD. BRITISH WIRE PRODUCTS LTD. THE BRITISH AVIATION INSURANCE CO. LTD. BROOM & WADE LTD. iy:i:M.mnr*jy BRITISH AVIATION SERVICES LTD. BRITISH INSULATED CALLENDER'S CABLES LTD. BROWN BROTHERS (AIRCRAFT) LTD. SMS^MMM BRITISH OVERSEAS AIRWAYS CORPORATION BUTLERS LIMITED AUTOMOBILE, AIRCRAFT AND MARITIME LAMPS BOM SEARCHLICHTS AND MOTOR ACCESSORIES BRITISH THOMSON-HOUSTON CO., THE CHLORIDE ELECTRICAL STORAGE CO. LTD. LIMITED (THE) Hxtie AIRCRAFT BATTERIES! Magnetos and Electrical Equipment COOPER & CO. (B'HAM) LTD. DUNFORD & ELLIOTT (SHEFFIELD) LTD. COOPERS I IDBSHU l Bala i IIIIKTI A. C. COSSOR LIMITED DUNLOP RUBBER CO., LTD. -

Imperial Airways

IMPERIAL AIRWAYS 1 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW.XV Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 2 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. G-ADSR, Ensign Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 3 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW15 Atlanta, G-ABPI, Imperial Airways, air to air, 1932. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 4 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBLF, Imperial Airways, 1929. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 5 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, 1937. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 6 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atlanta, G-ABTL, Astraea Imperial Airways, Royal Mail GR. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 7 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Atalanta, G-ABTK, Athena, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 8 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Argosy, G-EBLO, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 9 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 10 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 11 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. Argosy I, G-EBOZ, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 12 ARMSTRONG WHITWORTH. AW 27 Ensign, G-ADSR, Imperial Airways, air to air. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 13 AVRO. 652, G-ACRM, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 14 AVRO. 652, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 15 AVRO. Avalon, G-ACRN, Imperial Airways. Photograph, 9 x 14 cm. 6,00 16 BENNETT, D. C. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES -

Global Volatility Steadies the Climb

WORLD AIRLINER CENSUS Global volatility steadies the climb Cirium Fleet Forecast’s latest outlook sees heady growth settling down to trend levels, with economic slowdown, rising oil prices and production rate challenges as factors Narrowbodies including A321neo will dominate deliveries over 2019-2038 Airbus DAN THISDELL & CHRIS SEYMOUR LONDON commercial jets and turboprops across most spiking above $100/barrel in mid-2014, the sectors has come down from a run of heady Brent Crude benchmark declined rapidly to a nybody who has been watching growth years, slowdown in this context should January 2016 low in the mid-$30s; the subse- the news for the past year cannot be read as a return to longer-term averages. In quent upturn peaked in the $80s a year ago. have missed some recurring head- other words, in commercial aviation, slow- Following a long dip during the second half Alines. In no particular order: US- down is still a long way from downturn. of 2018, oil has this year recovered to the China trade war, potential US-Iran hot war, And, Cirium observes, “a slowdown in high-$60s prevailing in July. US-Mexico trade tension, US-Europe trade growth rates should not be a surprise”. Eco- tension, interest rates rising, Chinese growth nomic indicators are showing “consistent de- RECESSION WORRIES stumbling, Europe facing populist backlash, cline” in all major regions, and the World What comes next is anybody’s guess, but it is longest economic recovery in history, US- Trade Organization’s global trade outlook is at worth noting that the sharp drop in prices that Canada commerce friction, bond and equity its weakest since 2010. -

Journal of British Studies

Journal of British Studies 'The show is not about race': Custom, Screen Culture, and The Black and White Minstrel Show --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: 4811R2 Full Title: 'The show is not about race': Custom, Screen Culture, and The Black and White Minstrel Show Article Type: Original Manuscript Corresponding Author: Christine Grandy, Ph.D. University of Lincoln Lincoln, Lincolnshire UNITED KINGDOM Corresponding Author Secondary Information: Corresponding Author's Institution: University of Lincoln Corresponding Author's Secondary Institution: First Author: Christine Grandy, Ph.D. First Author Secondary Information: Order of Authors: Christine Grandy, Ph.D. Order of Authors Secondary Information: Abstract: In 1967, when the BBC was faced with a petition by the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) requesting an end to the televised variety programme, The Black and White Minstrel Show (1958-1978), producers at the BBC, the press, and audience members collectively argued that the historic presence of minstrelsy in Britain rendered the practice of blacking up harmless. This article uses Critical Race Theory as a useful framework for unpacking defences that hinged both on the colour-blindness of white British audiences, and the simultaneous existence of wider customs of blacking up within British television and film. I examine a range of 'screen culture' from the 1920s to the 1970s, including feature films, home movies, newsreels, and television, that provide evidence of the existence of blackface as a type of racialised custom in British entertainment throughout this period. Efforts by organisations such as CARD, black-press publications like Flamingo, and audiences of colour, to name blacking up and minstrelsy as racist in the late 1960s were met by fierce resistance from majority white audiences and producers, who denied their authority to do so. -

De Havilland Memorials V7

The de Havilland Aeronautical Technical School Association MEMORIALS of de HAVILLAND PEOPLE AND PLACES Introduction This list is based on that published in the Hatfield Aviation Association Newsletter Autumn 2005, reproduced in DHAeTSA Newsletter Spring 2006. It was compiled by the de Havilland Heritage Committee, headed by the late John Martin. It has been updated and the scope has been extended to include photographs, where possible, and to cover memorials such as awards and oral histories, also place names and sources of information. Locations Where practical, a post code is given. Where that may not be precise enough, or where there is no code (e.g. at Seven Barrows), the Ordnance Survey map reference and lat/long co-ordinates are given, also a mapcode. All satnav devices can accept lat/long as well as post codes. TomTom devices recognise mapcodes as well as postcodes. [Mapcodes can be used and generated at www.mapcode.com. In ‘I have a mapcode’ use GBR, e.g. GBR J9L.RPQ (Note space after GBR and dot between character groups. By default the location opens in Google Maps, from where Street View or Satellite View can selected, or one can choose at bottom of screen to display as TomTom map, Bing Map and others (not all work).] Abbreviations DHAM de Havilland Aircraft Museum deHMC de Havilland Moth Club DHSL de Havilland Support Ltd DHET de Havilland Engineering Trust RAeS Royal Aeronautical Society NOTE Sir Geoffrey de Havilland died on 21st May 1965, aged 82. His ashes were released from a Trident, piloted by John Cunningham, over Seven Barrows, site of his first successful flight. -

TEED!* * Find It Lower? We Will Match It

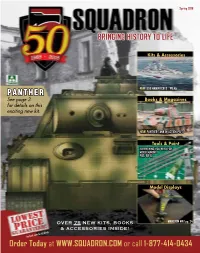

Spring 2018 BRINGING HISTORY TO LIFE Kits & Accessories NEW! USS HAWAII CB-3 PG.45 PANTHER See page 3 Books & Magazines for details on this exciting new kit. NEW! PANTHER TANK IN ACTION PG. 3 Tools & Paint EVERYTHING YOU NEED FOR MODELMAKING PGS. 58-61 Model Displays OVER 75 NEW KITS, BOOKS MARSTON MAT pg. 24 LOWEST PRICE GUARANTEED!* & ACCESSORIES INSIDE! * * See back cover for full details. Order Today at WWW.SQUADRON.COM or call 1-877-414-0434 Dear Friends, Now that we’ve launched into daylight savings time, I have cleared off my workbench to start several new projects with the additional evening light. I feel really motivated at this moment and with all the great new products we have loaded into this catalog, I think it is going to be a productive spring. As the seasons change, now is the perfect time to start something new; especially for those who have been considering giving the hobby a try, but haven’t mustered the energy to give it a shot. For this reason, be sure to check out pp. 34 - our new feature page especially for people wanting to give the hobby a try. With products for all ages, a great first experience is a sure thing! The big news on the new kit front is the Panther Tank. In conjunction with the new Takom (pp. 3 & 27) kits, Squadron Signal Publications has introduced a great book about this fascinating piece of German armor (SS12059 - pp. 3). Author David Doyle guides you through the incredible history of the WWII German Panzerkampfwagen V Panther. -

Brooklands Aerodrome & Motor

BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY (June 2017) Radley House Partnership BROOKLANDS AERODROME & MOTOR RACING CIRCUIT TIMELINE OF HERITAGE ASSETS CONTENTS Aerodrome Road 2 The 1907 BARC Clubhouse 8 Bellman Hangar 22 The Brooklands Memorial (1957) 33 Brooklands Motoring History 36 Byfleet Banking 41 The Campbell Road Circuit (1937) 46 Extreme Weather 50 The Finishing Straight 54 Fuel Facilities 65 Members’ Hill, Test Hill & Restaurant Buildings 69 Members’ Hill Grandstands 77 The Railway Straight Hangar 79 The Stratosphere Chamber & Supersonic Wind Tunnel 82 Vickers Aviation Ltd 86 Cover Photographs: Aerial photographs over Brooklands (16 July 2014) © reproduced courtesy of Ian Haskell Brooklands Heritage Partnership CONSULTATION COPY Radley House Partnership Timelines: June 2017 Page 1 of 93 ‘AERODROME ROAD’ AT BROOKLANDS, SURREY 1904: Britain’s first tarmacadam road constructed (location?) – recorded by TRL Ltd’s Library (ref. Francis, 2001/2). June 1907: Brooklands Motor Circuit completed for Hugh & Ethel Locke King and first opened; construction work included diverting the River Wey in two places. Although the secondary use of the site as an aerodrome was not yet anticipated, the Brooklands Automobile Racing Club soon encouraged flying there by offering a £2,500 prize for the first powered flight around the Circuit by the end of 1907! February 1908: Colonel Lindsay Lloyd (Brooklands’ new Clerk of the Course) elected a member of the Aero Club of Great Britain. 29/06/1908: First known air photos of Brooklands taken from a hot air balloon – no sign of any existing route along the future Aerodrome Road (A/R) and the River Wey still meandered across the road’s future path although a footbridge(?) carried a rough track to Hollicks Farm (ref. -

Unclaimed Bank Balances

Unclaimed Bank Balances “Section 126 of the Banking Services Act requires the publication of the following data in a newspaper at least two (2) times over a one (1) year period.” This will give persons the opportunity to claim these monies. If these monies remain unclaimed at the end of the year, they will become a part of the revenues of the Jamaican Government. SAGICOR BANK BALANCE Name Last Transaction Date Account Number Balance Name Last Transaction Date Account Number Balance JMD JMD ALMA J BROWN 7-Feb-01 5500866545 32.86 ALMA M HENRY 31-Dec-97 5501145809 3,789.62 0150L LYNCH 13-Jun-86 5500040485 3,189.49 ALMAN ARMSTRONG 22-Nov-96 5500388252 34.27 A A R PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES CENTRE 30-Sep-97 5500073766 18,469.06 ALMANEITA PORTER 7-Nov-02 5500288665 439.42 A F FRANCIS 29-Sep-95 5500930588 23,312.81 ALMARIE HOOPER 19-Jan-98 5500472978 74.04 A H BUILDINGS JAMAICA LTD 30-Sep-93 5500137705 12,145.92 ALMENIA LEVY 27-Oct-93 5500966582 40,289.27 A LEONARD MOSES LTD 20-Nov-95 5500108993 531,889.69 ALMIRA SOARES 18-Feb-03 5501025951 12,013.42 A ROSE 13-Jun-86 5500921767 20,289.21 ALPHANSO C KENNEDY 8-Jul-02 5500622379 34,077.58 AARON H PARKE 27-Dec-02 5501088128 10,858.10 ALPHANSO LOVELACE 12-Dec-03 5500737354 69,295.14 ADA HAMILTON 30-Jan-83 5500001528 35,341.90 ALPHANSON TUCKER 10-Jan-96 5500969131 48,061.09 ADA THOMPSON 5-May-97 5500006511 9,815.70 ALPHANZO HAMILTON 12-Apr-01 5500166397 8,633.90 ADASSA DOWDEN SCHOLARSHIP 20-Jan-00 5500923328 299.66 ALPHONSO LEDGISTER 15-Feb-00 5500087945 58,725.08 ADASSA ELSON 28-Apr-99 5500071739 71.13 -

De Havilland Memorials V8

The de Havilland Aeronautical Technical School Association MEMORIALS of de HAVILLAND PEOPLE AND PLACES Introduction This list is based on that published in the Hatfield Aviation Association Newsletter Autumn 2005, reproduced in DHAeTSA Newsletter Spring 2006. It was compiled by the de Havilland Heritage Committee, headed by the late John Martin. It has been updated and the scope has been extended to include photographs, where possible, and to cover memorials such as awards and oral histories, also place names and sources of information. Locations Where practical, a post code is given. Where that may not be precise enough, or where there is no code (e.g. at Seven Barrows), the Ordnance Survey map reference and lat/long co-ordinates are given, also a mapcode. All satnav devices can accept lat/long as well as post codes. TomTom devices recognise mapcodes as well as postcodes. [Mapcodes can be used and generated at www.mapcode.com. In ‘I have a mapcode’ use GBR, e.g. GBR J9L.RPQ (Note space after GBR and dot between character groups. By default the location opens in Google Maps, from where Street View or Satellite View can selected, or one can choose at bottom of screen to display as TomTom map, Bing Map and others (not all work).] Abbreviations DHAM de Havilland Aircraft Museum deHMC de Havilland Moth Club DHSL de Havilland Support Ltd DHET de Havilland Engineering Trust RAeS Royal Aeronautical Society NOTE Sir Geoffrey de Havilland died on 21st May 1965, aged 82. His ashes were released from a Trident, piloted by John Cunningham, over Seven Barrows, site of his first successful flight. -

Annual Report 2009

BBA Aviation plc plc BBA Aviation Registered Offi ce 20 Balderton Street London, W1K 6TL Telephone +44 (0)20 7514 3999 Annual Report 2009 Fax +44 (0)20 7408 2318 Annual Report 2009 Registered in England Company number: 53688 www.bbaaviation.com This Annual Report is addressed solely to members of BBA Aviation plc as a body. Neither the Company nor its directors accept or assume responsibility to any person for this Annual Report beyond the responsibilities arising from the production of this Annual Report under the requirements of applicable English company law. Sections of this Annual Report, including the Directors’ Report and Directors’ Remuneration Report contain forward-looking statements including, without limitation, statements relating to: future demand and markets of the Group’s products and services; research and development relating to new products and services; liquidity and capital; and implementation of restructuring plans and efficiencies. These forward- looking statements involve risks and uncertainties because they relate to events and depend on circumstances that will or may occur in the future. Accordingly, actual results may differ materially from those set out in the forward-looking statements as a result of a variety of factors including, without limitation: changes in interest and exchange rates, commodity prices and other economic conditions; negotiations with customers relating to renewal of contracts and future volumes and prices; events affecting international security, including global health issues and terrorism; changes in regulatory environment; and the outcome of litigation. The Company undertakes no obligation to publicly update or revise any forward-looking statement, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.