A Manifesto for Nonviolent Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

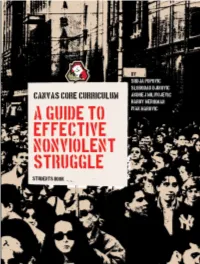

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

Authoritarian Politics and the Outcome of Nonviolent Uprisings

Authoritarian Politics and the Outcome of Nonviolent Uprisings Jonathan Sutton Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies/Te Ao o Rongomaraeroa University of Otago/Te Whare Wānanga o Otāgo July 2018 Abstract This thesis examines how the internal dynamics of authoritarian regimes influence the outcome of mass nonviolent uprisings. Although research on civil resistance has identified several factors explaining why campaigns succeed or fail in overthrowing autocratic rulers, to date these accounts have largely neglected the characteristics of the regimes themselves, thus limiting our ability to understand why some break down while others remain cohesive in the face of nonviolent protests. This thesis sets out to address this gap by exploring how power struggles between autocrats and their elite allies influence regime cohesion in the face of civil resistance. I argue that the degeneration of power-sharing at the elite level into personal autocracy, where the autocrat has consolidated individual control over the regime, increases the likelihood that the regime will break down in response to civil resistance, as dissatisfied members of the ruling elite become willing to support an alternative to the status quo. In contrast, under conditions of power-sharing, elites are better able to guarantee their interests, thus giving them a greater stake in regime survival and increasing regime cohesion in response to civil resistance. Due to the methodological challenges involved in studying authoritarian regimes, this thesis uses a mixed methods approach, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data and methods to maximise the breadth of evidence that can be used, balance the weaknesses of using either approach in isolation, and gain a more complete understanding of the connection between authoritarian politics and nonviolent uprisings. -

Open Eppinger Final Thesis Submission.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY THE WRITER’S ROLE IN NONVIOLENT RESISTANCE: VÁCLAV HAVEL AND THE POWER OF LIVING IN TRUTH MARGARET GRACE EPPINGER SPRING 2019 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in History and English with honors in History Reviewed and approved* by the following: Catherine Wanner Professor of History, Anthropology, and Religious Studies Thesis Supervisor Cathleen Cahill Associate Professor of History Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT In 1989, Eastern Europe experienced a series of revolutions that toppled communist governments that had exercised control over citizens’ lives for decades. One of the most notable revolutions of this year was the Velvet Revolution, which took place in Czechoslovakia. Key to the revolution’s success was Václav Havel, a former playwright who emerged as a political leader as a result of his writing. Havel went on to become the first president following the regime’s collapse, and is still one of the most influential people in the country’s history to date. Following the transition of Havel from playwright to political dissident and leader, this thesis analyzes the role of writers in nonviolent revolutions. Havel’s ability to effectively articulate his ideas gave him moral authority in a region where censorship was the norm and ultimately elevated him to a position of leadership. His role in Czechoslovak resistance has larger implications for writers and the significance of their part in revolutionary contexts. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... iii Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 Chapter 1 What is Resistance? ................................................................................... -

Strategic Nonviolent Power: the Science of Satyagraha Mark A

STRATEGIC NONVIOLENT POWER Global Peace Studies SERIES EDITOR: George Melnyk Global Peace Studies is an interdisciplinary series devoted to works dealing with the discourses of war and peace, conflict and post-conflict studies, human rights and inter- national development, human security, and peace building. Global in its perspective, the series welcomes submissions of monographs and collections from both scholars and activists. Of particular interest are works on militarism, structural violence, and postwar reconstruction and reconciliation in divided societies. The series encourages contributions from a wide variety of disciplines and professions including health, law, social work, and education, as well as the social sciences and humanities. SERIES TITLES: The ABCs of Human Survival: A Paradigm for Global Citizenship Arthur Clark Bomb Canada and Other Unkind Remarks in the American Media Chantal Allan Strategic Nonviolent Power: The Science of Satyagraha Mark A. Mattaini STRATEGIC THE SCIENCE OF NONVIOLENT SATYAGRAHA POWER MARK A. MATTAINI Copyright © 2013 Mark A. Mattaini Published by AU Press, Athabasca University 1200, 10011 – 109 Street, Edmonton, AB T5J 3S8 ISBN 978-1-927356-41-8 (print) 978-1-927356-42-5 (PDF) 978-1-927356-43-2 (epub) A volume in Global Peace Studies ISSN 1921-4022 (print) 1921-4030 (digital) Cover and interior design by Marvin Harder, marvinharder.com. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Book Printers. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Mattaini, Mark A. Strategic nonviolent power : the science of satyagraha / Mark A. Mattaini. (Global peace studies, ISSN 1921-4022) Includes bibliographical references and index. Issued also in electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-927356-41-8 1. -

Democratic Movement' As a Politically Harmful Process Since the Mid-1950S

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified June, 2007 Non-conformism. Evolution of the 'democratic movement' as a politically harmful process since the mid-1950s. Folder 9. The Chekist Anthology. Citation: “Non-conformism. Evolution of the 'democratic movement' as a politically harmful process since the mid-1950s. Folder 9. The Chekist Anthology.,” June, 2007, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Contributed to CWIHP by Vasili Mitrokhin. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113665 Summary: In this transcript, Mitrokhin points out that according to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) bourgeois ideology affected cohesion of the Soviet society in three major ways: 1) by creating opposition and manipulating people’s personal weaknesses in order to pull apart the Soviet organism; 2) by inflaming disputes between younger and older generations, members of intelligentsia and working class; 3) by building up everyday propagandist pressure. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Russian Transcription [Translation unavailable. Please see original. Detailed summary below.] In this transcript, Mitrokhin points out that according to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) bourgeois ideology affected cohesion of the Soviet society in three major ways: 1) by creating opposition and manipulating people's personal weaknesses in order to pull apart the Soviet organism; 2) by inflaming disputes between younger and older generations, members of intelligentsia and working class; 3) by building up everyday propagandist pressure. The democratic movement originated in 1950s. It largely consisted of artists and literary figures of the time who advocated the conception of a democratic society. Mitrokhin indicates that the Soviet government also regarded all revisionists, nationalists, Zionists, members of church and religious sects to be a part of the Democratic movement. -

Orange-Revolution-Study-Guide-2.Pdf

Study Guide Credits A Force More Powerful Films presents Produced and Directed by STEVE YORK Executive Producer PETER ACKERMAN Edited by JOSEPH WIEDENMAYER Managing Producer MIRIAM ZIMMERMAN Original Photography ALEXANDRE KVATASHIDZE PETER PEARCE Associate Producers SOMMER MATHIS NATALIYA MAZUR Produced by YORK ZIMMERMAN Inc. www.OrangeRevolutionMovie.com DVDs for home viewing are DVDs for educational use must available from be purchased from OrangeRevolutionMovie.coM The CineMa Guild and 115 West 30th Street, Suite 800 AForceMorePowerful.org New York, NY 10001 Phone: (800) 723‐5522 Also sold on Amazon.com Fax: (212) 685‐4717 eMail: [email protected] http://www.cineMaguild.coM Study Guide produced by York ZiMMerMan Inc. www.yorkziM.coM in association with the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict www.nonviolent‐conflict.org Writers: Steve York, Hardy MerriMan MiriaM ZiMMerMan & Cynthia Boaz Layout & Design: Bill Johnson © 2010 York ZiMMerMan Inc. Table of Contents An Election Provides the Spark ......................... 2 A Planned Spontaneous Revolution ................. 4 Major Characters .............................................. 6 Other Players .................................................... 7 Ukraine Then and Now ..................................... 8 Ukraine Historical Timeline ............................... 9 Not the First Time (Or the Last) ....................... 10 Epilogue ........................................................... 11 Additional Resources ....................................... 12 Questions -

Tweeting the Revolution

EGYPT IN THE ARAB SPRING TWEETING THE REVOLUTION The Role of Social Media in Political Mobilisation Daniel Domingues Class 6k Maturitätsarbeit 2013/2014 Supervision: Marianne Rosatzin Kantonsschule Zürcher Unterland Daniel Domingues Date of Submission: 6 January 2013 Furtrainstrasse 20 8180 Bülach 0445546228 [email protected] TWEETING THE REVOLUTION: EGYPT IN THE ARAB SPRING Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................ 1 1 Introduction ................................................................................................. 3 2 Communication Theories of the 21st Century ............................................... 9 2.1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Social Media .................................................................................................... 9 2.2.1 Facebook .................................................................................................. 9 2.2.2 Twitter ..................................................................................................... 10 2.2.3 Weblog .................................................................................................... 11 2.3 Communication Theories of the 21st Century .................................................. 11 2.4 Criticism ......................................................................................................... 13 2.5 Social -

91 Template Revolutions

Template Revolutions: Marketing U.S. Regime Change in Eastern Europe Gerald Sussman and Sascha Krader Portland State University Keywords : propaganda, U.S. foreign policy, democracy, Eastern Europe, National Endowment for Democracy Abstract Between 2000 and 2005, Russia-allied governments in Serbia, Georgia, Ukraine, and (not discussed in this paper) Kyrgyzstan were overthrown through bloodless upheavals. Though Western media generally portrayed these coups as spontaneous, indigenous and popular (‘people power’) uprisings, the ‘color revolutions’ were in fact outcomes of extensive planning and energy ─ much of which originated in the West. The United States, in particular, and its allies brought to bear upon post-communist states an impressive assortment of advisory pressures and financing mechanisms, as well as campaign technologies and techniques, in the service of ‘democracy assistance’. Their arsenals included exit and opinion polling, focus groups for ‘revolutionary messaging’, and methods and training in ‘strategic nonviolent conflict’. Among the key foreign agents involved in the process of creating ‘transitional democracies’, as discussed in this study, are the United States Agency for International Development, the National Endowment for Democracy and its funded institutes, George Soros’s Open Society Institute, Freedom House, and the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict. These developments are conceived as aspects of the larger neoliberal program of opening the Eastern European region for commercial, strategic military, cultural, and political domination by the G-7 countries. Four types of foreign assistance studied are: (1) political; (2) financial; (3) technical training; and (4) marketing (propaganda). Introduction The dissolution of Soviet power throughout the region of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) and Central Asia excited a new kind of Western intervention, a ‘soft imperialism’ described in official lexicon as ‘democracy promotion’. -

Revolution, Non-Violence, and the Arab Uprisings

George Lawson Revolution, non-violence, and the Arab Uprisings Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Lawson, George (2015) Revolution, non-violence, and the Arab Uprisings. Mobilization: An International Quarterly . ISSN 1086-671X (In Press) © 2015 Mobilization: An International Quarterly This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/63156/ Available in LSE Research Online: August 2015 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Revolution, Non-Violence, and the Arab Uprisings George Lawson, London School of Economics Abstract This article combines insights from the literature on revolutions with that on non- violent protest in order to assess the causes and outcomes of the Arab Uprisings. The article makes three main arguments: first, international -

1 the BROOKINGS INSTITUTION VELVET REVOLUTIONS from PRAGUE to TEHRAN: WHAT, IF ANYTHING, SHOULD WE DO ABOUT THEM? Washington, D

VELVET-2009/10/06 1 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION VELVET REVOLUTIONS FROM PRAGUE TO TEHRAN: WHAT, IF ANYTHING, SHOULD WE DO ABOUT THEM? Washington, D.C. Tuesday, October 6, 2009 PARTICIPANTS: Introduction and Moderator: TED PICCONE Senior Fellow and Deputy Director, Foreign Policy The Brookings Institution Featured Speaker: TIMOTHY GARTON ASH Professor of European Studies University of Oxford Panelists: THOMAS CAROTHERS Vice President for Studies Carnegie Endowment for International Peace SUZANNE MALONEY Senior Fellow The Brookings Institution * * * * * ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 VELVET-2009/10/06 2 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. PICCONE: Good morning. My name is Ted Piccone. I’m a Senior Fellow and Deputy Director for Foreign Policy here at Brookings. Welcome to this event on the Velvet Revolutions. This is an auspicious occasion of the 20th Anniversary of the Velvet Revolutions of 1989, which was, as most of us remember, a time of great tumult and excitement, not only in places like Prague and Warsaw but also throughout the world, as the curve of history seemed to bend toward a new paradigm of peaceful democratic change. Here, at Foreign Policy at Brookings, we’re marking this historic milestone by focusing our thoughts on a critical piece of that story -- the role of people power in upsetting the status quo and establishing a different model of governance built on the principles of representative democracy, human rights and liberal ideals. Since those heady days of 1989, a lot has happened around the world to lend both hope and dismay about the prospects for nonviolent methods of political reform.