Tweeting the Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

New Tahrir Square (Planting Democracy)

Hochshule Anhalt (FH) Anhalt University of Applied Sciences Master of Landscape Architecture Anhalt University of Applied Sciences (October, 2013) New Tahrir Square (Planting Democracy) 3URI$OH[DQGHU0.DGHU¿UVWH[DPLQHU%\,VVDP$EG(OODWLI 3URI(LQDU.UHW]OHUVHFRQGH[DPLQHU Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) '(&/$5$7,212)$87+256+,3 ,FHUWLI\WKDWWKHPDWHULDOFRQWDLQHGLQWKLV0DVWHU7KHVLVLVP\RZQZRUNDQGGRHVQRFRQWDLQXQDFNQRZOHGJHGZRUNRIRWKHUV :KHUH,KDYHFRQVXOWHGWKHSXEOLVKHGZRUNRIRWKHUVWKLVLVDOZD\VFOHDUO\DWWULEXWHG :KHUH,KDYHTXRWHGIURPWKHZRUNRIRWKHUVWKHVRXUFHLVDOZD\VJLYHQ:LWKWKHH[FHSWLRQRIVXFKTXRWDWLRQVWKH ZRUNRIWKLVWKHVLVLVHQWLUHO\P\RZQ 7KLVGLVVHUWDWLRQKDVQRWEHHQVXEPLWWHGIRUWKHDZDUGRIDQ\RWKHUGHJUHHRUGLSORPDLQDQ\RWKHULQVWLWXWLRQ __________________________________ ,VVDP$EG(OODWLI 6WXGHQW,' %HUQEXUJWKRI2FWREHU ABSTRACT Author: Issam Abd Ellatif !esis Title: New Tahrir Square (( PLANTING DEMOCRACY)) Keywords: Cairo, Tahrir, Planting democracy, revolution, February 2011. Abstract: Cairo give its tourists an unbelievable selection of attractions; it is a mixture of old and new as it include many former cities and their monuments.In fact the area of the city can be return to 4225 BC. cairo limited by the desert to the west and east,and the Nile delta to the north, the city is located on both banks and along 40km south to north of the river Nile. !e city centre is full of universities, governmental o#ces, institutions, commercial establishments, and countless hotels, creating a intensive pattern of constant activity. !e ever-busy Tahrir square is one of the major and largest public squares; the centre of the city. It's really di#cult task to come up with a proposal for Tahrir Square, the icon of the Egyptian revolution, which has not $nished yet. I develop proposals and for the tahrir square. Finally, I will present the design for the Egyptian Government, providing ideas, concepts and %at planes. I also propose solutions to current problems, by identifying potentials and taking advantages from them and by creating methods to pursuing these solutions. -

Download Transcript

Getting Real NOW: Documenting Press Freedom & Impact - Transcript Cassidy Dimon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to our panel. We're going to take a couple minutes here and let the room populate before we begin. Just hold tight. Thank you. Hello all. Again thank you for joining. I see a lot of you have joined recently. We're going to take just two more minutes here and let people get into the room. And we will get started at approximately 5:03. Thank you. Carrie Lozano: Good evening, everyone. I know some of you are still joining us tonight. But I'm so happy to kick off this conversation. I honestly can't imagine anywhere else I'd rather be right now. So thank you for joining us for this second installment of Getting Real Now. My name is Carrie Lozano. I am the director of IDA's Enterprise Documentary Fund. I would like to acknowledge that I am in northern California on Ohlone land. And as many of you might know, we are encircled by fire and smoke throughout the west coast. And I am just reminded that in Native tradition, it's the Earth's way of renewing its soil and making it fertile to burn. And while it might be uncomfortable for us, it's the planet's way of healing itself. And so I hope we can all hold space together and honor all that the planet is doing to correct itself. Before I introduce our speakers, I really want to thank all of the sponsors and supporters that make these conversations and getting real in the digital space possible. -

Tweetstorming in the Language Classroom: Impact on EFL Tertiary Students’ Ideational Fluency and Syntactic Complexity

كلية التربية المجلة التربوية *** Tweetstorming in the Language Classroom: Impact on EFL Tertiary Students’ Ideational Fluency and Syntactic Complexity Abdullah Mahmoud Ismail Ammar Assistant Professor of TEFL Sohag Faculty of Education . اجمللة الرتبوية ـ العدد السادس واﻷربعون ـ أكتوبر 1026م ــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــــ العدد )46( أكتوبر6106م ABSTRACT The last few years have witnessed a paradigm shift in educational settings where language educators and practitioners have turned their focus from traditional face-to-face classroom practices to more hybrid and virtual language teaching/learning methodologies. This paradigm shift gained momentum with the introduction of Web 2.00 tools and social media applications and the increased tendency in education and workplace towards more technology-driven practices and solutions. The current study reports on an experimental treatment to employ Tweetstorming in writing classes of tertiary students and studying the impact on their ideational fluency and syntactic complexity. Participants were EFL tertiary students enrolled in Writing I course of the English Study program of Abu Dhabi University. Results of the study indicate that using Tweetstorming in the writing classes of tertiary EFL students brought about significant gains in their ideational fluency and syntactic complexity. Details of the instructional -

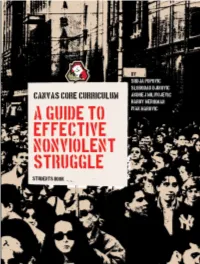

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #Metoo

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 49 Issue 1 Article 3 2019 Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo Nicole Hallett University of Buffalo School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Hallett, Nicole (2019) "Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #MeToo," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 49 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol49/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMIGRANT WOMEN IN THE SHADOW OF #METOO Nicole Hallett* I. INTRODUCTION We hear Daniela Contreras’s voice, but we do not see her face in the video in which she recounts being raped by an employer at the age of sixteen.1 In the video, one of four released by a #MeToo advocacy group, Daniela speaks in Spanish about the power dynamic that led her to remain silent about her rape: I couldn’t believe that a man would go after a little girl. That a man would take advantage because he knew I wouldn’t say a word because I couldn’t speak the language. Because he knew I needed the money. Because he felt like he had the power. And that is why I kept quiet.2 Daniela’s story is unusual, not because she is an undocumented immigrant who was victimized -

A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications

Journal of Applied Communications Volume 94 Issue 3 Nos. 3 & 4 Article 2 A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications Katie Allen Katie Abrams Courtney Meyers See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/jac This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Allen, Katie; Abrams, Katie; Meyers, Courtney; and Shultz, Alyx (2010) "A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications," Journal of Applied Communications: Vol. 94: Iss. 3. https://doi.org/10.4148/1051-0834.1189 This Professional Development is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Applied Communications by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Little Birdie Told Me About Agriculture: Best Practices and Future Uses of Twitter in Agriculutral Communications Abstract Social media sites, such as Twitter, are impacting the ways businesses, organizations, and individuals use technology to connect with their audiences. Twitter enables users to connect with others through 140-character messages called “tweets” that answer the question, “What’s happening?” Twitter use has increased exponentially to more than five million active users but has a dropout rate of more than 50%. Numerous agricultural organizations have embraced the use of Twitter to promote their products and agriculture as a whole and to interact with audiences in a new way. -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

Twitter: a Uses and Gratifications Approach

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 “WHAT’S HAPPENING” @TWITTER: A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS APPROACH Corey Leigh Ballard University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ballard, Corey Leigh, "“WHAT’S HAPPENING” @TWITTER: A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS APPROACH" (2011). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 155. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/155 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS “WHAT’S HAPPENING” @TWITTER: A USES AND GRATIFICATIONS APPROACH The uses and gratifications approach places power in the hands of the audience and is a helpful perspective when trying to understand media usage, exposure, and effects. However, while the uses and gratifications approach has been applied regularly to traditional media, research explaining why people use new social media networks as well as the gratifications they obtain from them is scarce at best. This thesis provides a comprehensive overview of the uses and gratifications approach as well as the current literature about social media networks. An argument is built within the thesis to study Twitter as one social media network through the uses and gratifications theoretical lens. Research questions are provided and a survey of 216 college undergraduates was conducted. Results show that people use a variety of Twitter functions, that the gratifications sought from Twitter are not the gratifications obtained from Twitter, and that people are careful about the types of information they share on the social media network. -

Twitter and Society

TWITTER AND SOCIETY Steve Jones General Editor Vol. 89 The Digital Formations series is part of the Peter Lang Media and Communication list. Every volume is peer reviewed and meets the highest quality standards for content and production. PETER LANG New York Washington, D.C./Baltimore Bern Frankfurt Berlin Brussels Vienna Oxford TWITTER AND SOCIETY Edited by Katrin Weller, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt, & Cornelius Puschmann PETER LANG New York Washington, D.C./Baltimore Bern Frankfurt Berlin Brussels Vienna Oxford Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Twitter and society / edited by Katrin Weller, Axel Bruns, Jean Burgess, Merja Mahrt, Cornelius Puschmann. pages cm. ----- (Digital formations; vol. 89) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Twitter. 2. Online social networks. 3. Internet-----Social aspects. 4. Information society. I. Weller, Katrin, editor of compilation. HM743.T95T85 2 006.7’54-----dc23 2013018788 ISBN 978-1-4331-2170-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-4331-2169-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-4539-1170-9 (e-book) ISSN 1526-3169 Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the ‘‘Deutsche Nationalbibliografie’’; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de/. Cover art: Klee, Paul (1879---1940): Twittering Machine (Zwitscher-Maschine), 1922. New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Watercolor, and pen and ink on oil transfer drawing on paper, mounted on cardboard. DIGITAL IMAGE ©2012, The Museum of Modern Art/Scala, Florence. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council of Library Resources. -

Synopsis of Yamamoto's Essay Social Media and the Arab Spring: the Mobilization and Transparency Revolutions (Tatsuya Yamamoto)

Vol. Special Feature: Democracy for Better or Worse 77 2012 Synopsis of Yamamoto's Essay Social Media and the Arab Spring: The Mobilization and Transparency Revolutions (Tatsuya Yamamoto) Political scientist Samuel Huntington talked about "Third Wave Democracy" in the world more than twenty years ago. This wave had failed to reach Arab countries fully until last year, when authoritarian Middle Eastern regimes began to collapse under the influence of the Arab Spring, which started with the "Jasmine Revolution" in Tunisia. There is no doubt that social media, such as Facebook and Twitter, contributed significantly to this change. Tatsuya Yamamoto, who has been studying Internet censorship in the Arab world, examines the relationship between democratization/democracy and social media using Egypt as an example. While spring has definitely arrived, there is no guarantee that it will last. This is the cautious message we can derive from Yamamoto's argument. * Wael Ghonim, an Egyptian computer engineer and an executive at Google in the United States, who personally participated in this movement toward democratization, details the relationship between the democratization of Egypt and social media in his book, Revolution 2.0 (Fourth Estate, 2012). Shocked by a photo that showed the body of Khaled Said, a youth who was mercilessly beaten to death by two police officers in Tunisia, Ghonim made the point that "we are all Khaled Said" to his fellow Facebook users. Ghonim's point struck a chord with many people, including angry youths in Egypt, and this recognition led the pro-democracy movement to move from the virtual world to the real world. -

Greta Thunberg: the Voice of Our Planet

Berkeley Leadership Case Series 21-180-017 February 16, 2021 1 Greta Thunberg: The Voice of Our Planet “Over 1,000 students and adults sit alongside Greta on the last day of the school strike. Media and news reporters from several different countries gather around the crowd at Mynttorget Square. Many people believe she has achieved more for the climate than most politicians and the mass media has done in years. But Greta seems to disagree. “Nothing has changed,” she says. “The emissions continue to increase and there is no change in sight.” - Malena Ernman (Greta Thunberg’s mother) i At the age of 17, Greta Thunberg is one of the most powerful voices in the global movement addressing Earth’s climate crisis. Thunberg has successfully stepped up to create a call to action, reached a massive audience, and rallied support across multiple nations. Her activism and sudden rise to the world stage has earned her numerous honors as the youngest Time Person of the Year and two-time Nobel Peace Prize nominee. “The Greta Thunberg Effect”, as journalists have dubbed it, has compelled politicians and government officials to focus on climate change. Despite her accolades, however, Thunberg believes there remains much to do before the planet is truly safe and healthy. “Our house is still on fire,” she warned earlier this year. Going forward, how can Thunberg scale her movement to deliver substantive policy change? The Problem of Climate Change Since the mid-20th century, scientists and researchers have attributed the exponential increase in global temperature (see Exhibit 1) to an increase in human activity.