Immigrant Women in the Shadow of #Metoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Feminism in the Arab Gulf

MIT Center for Intnl Studies | Starr Forum: Digital Feminism in the Arab Gulf MICHELLE I'm Michelle English, and on behalf of the MIT Center for International Studies, welcome you to ENGLISH: today's Starr Forum. Before we get started, I'd like to mention that this is our last planned event for the fall. However, we do have many, many events planned for the spring. So if you haven't already, please take time to sign up to get our event notices. Today's talk on digital feminism in the Arab Gulf states is co-sponsored by the MIT Women's and Gender Studies program, the MIT History department, and the MIT Press bookstore. In typical fashion, our talk will conclude with Q&A with the audience. And for those asking questions, please line up behind the microphones. We ask that you to be considerate of time and others who want to ask questions. And please also identify yourself and your affiliation before asking your question. Our featured speaker is Mona Eltahawy, an award winning columnist and international public speaker on Arab and Muslim issues and global feminism. She is based in Cairo and New York City. Her commentaries have appeared in multiple publications and she is a regular guest analyst on television and radio shows. During the Egypt Revolution in 2011, she appeared on most major media outlets, leading the feminist website Jezebel to describe her as the woman explaining Egypt to the West. In November 2011, Egyptian riot police beat her, breaking her left arm and right hand, and sexually assaulted her, and she was detained for 12 hours by the Interior Ministry and Military Intelligence. -

She Is Not a Criminal

SHE IS NOT A CRIMINAL THE IMPACT OF IRELAND’S ABORTION LAW Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2015 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2015 Index: EUR 29/1597/2015 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Stock image: Female patient sitting on a hospital bed. © Corbis amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Executive summary ................................................................................................... 6 -

Download Transcript

Getting Real NOW: Documenting Press Freedom & Impact - Transcript Cassidy Dimon: Hello, everyone. Welcome to our panel. We're going to take a couple minutes here and let the room populate before we begin. Just hold tight. Thank you. Hello all. Again thank you for joining. I see a lot of you have joined recently. We're going to take just two more minutes here and let people get into the room. And we will get started at approximately 5:03. Thank you. Carrie Lozano: Good evening, everyone. I know some of you are still joining us tonight. But I'm so happy to kick off this conversation. I honestly can't imagine anywhere else I'd rather be right now. So thank you for joining us for this second installment of Getting Real Now. My name is Carrie Lozano. I am the director of IDA's Enterprise Documentary Fund. I would like to acknowledge that I am in northern California on Ohlone land. And as many of you might know, we are encircled by fire and smoke throughout the west coast. And I am just reminded that in Native tradition, it's the Earth's way of renewing its soil and making it fertile to burn. And while it might be uncomfortable for us, it's the planet's way of healing itself. And so I hope we can all hold space together and honor all that the planet is doing to correct itself. Before I introduce our speakers, I really want to thank all of the sponsors and supporters that make these conversations and getting real in the digital space possible. -

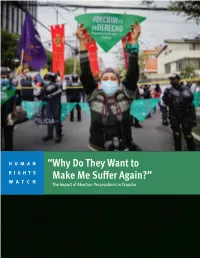

“Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” the Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador

HUMAN “Why Do They Want to RIGHTS WATCH Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JULY 2021 ISBN: 978-1-62313-919-3 “Why Do They Want to Make Me Suffer Again?” The Impact of Abortion Prosecutions in Ecuador Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................... 8 To the Presidency ................................................................................................................... -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

MENA Women News Briefdownload

May 29: Afghan women denied justice over violence, United Nations says “A law meant to protect Afghan women from violence is being undermined by authorities who routinely refer even serious criminal cases to traditional mediation councils that fail to protect victims, the United Nations said on Tuesday. The Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law, passed in 2009, was a centerpiece of efforts to improve protection for Afghan women, who suffer widespread violence in one of the worst countries in the world to be born female.” (Reuters) May 31: Female Genital Mutilation is Declared Religiously Forbidden in Islam “Egyptian Dar Al-Iftaa declared that female genital mutilation (FGM) is religiously forbidden on May 30, 2018, adding that banning FGM should be a religious duty due to its harmful effects on the body. Dar Al- Iftaa also explained that FGM is not mentioned in Islamic laws and that it only still occurs because it’s considered to be a social norm in the rural areas and some poor parts of Egypt. FGM is considered as an attack on religion through damaging the most sensitive organ in the female body. In Islam, protecting the body from any harm is a must and mutilation violates this rule.” (Egypt Today) June 4: Government proposes new draft law to ban early marriage “Egypt's government has proposed a new draft law that includes amendments to the child law article 12 of 1996, which states cases in which parents could be deprived from the authority of guardianship over the girl or her property…Hawary told Egypt Today that this bill stipulates that a father who forces his daughter to get married before reaching the age of marriage will be deprived from the authority of guardianship over the girl or her property.” (Egypt Today) June 4: Youth, women, and minorities have valid concerns “Iranian President Hassan Rouhani admitted on Friday that the youth, women and minorities have legitimate grievances, Anadolu Agency reported, citing the Iranian presidency’s official website. -

Constructing #Metoo

Constructing #MeToo A Critical Discourse Analysis of the German News Media’s Discursive Construction of the #MeToo Movement Wiebke Eilermann K3| School of Arts and Communications Media and Communication Studies Master’s Thesis (Two-Year), 15 ECTS Spring 2018 Supervisor: Tina Askanius Examiner: Erin Cory Date of Examination: June 21st 2018 Abstract Purpose: The purpose of this thesis is to examine how German newspapers discursively constructed the #MeToo movement in order to determine whether the hashtag campaign was legitimized or delegitimized. The ideological construction can be seen as an indication of social change or respectively the upholding of the status quo in regard to gender equality. Of further interest was how the coverage can be perceived as an example of a post-feminist sensibility in mainstream media. Approach: Relevant articles published during two time periods in 2017 and 2018, following defining events of the #MeToo movement, were retrieved from selected publications, including Die Welt, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Süddeutsche Zeitung and Die Zeit. A qualitative critical discourse analysis applying Norman Fairclough’s (1995) three-dimensional approach was performed on 41 newspaper articles. Results: Through analysis, three main discursive strands emerged: (1) supportive coverage of #MeToo (2) opposing coverage of #MeToo (3) #MeToo as complex. The degree to which the articles adhered to these positions varied from publication to publication. The most conservative publication largely delegitimized the movement by, amongst others, drawing on a post-feminist discourse. Whereas the liberal publications predominantly constructed #MeToo as legitimate. Overall, there was little discussion of marginalized voices and opportunities for progressive solutions leading to social change. -

Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre

Re: Supplementary Information on Kenya, Scheduled for Review by the Pre-sessional Working Group of the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights during its 56th Session Distinguished Committee Members, This letter is intended to supplement the periodic report submitted by the government of Kenya, which is scheduled to be reviewed during the 56th pre-session of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (the Committee). The Center for Reproductive Rights (the Center) a global legal advocacy organization with headquarters in New York and, and regional offices in Nairobi, Bogotá, Kathmandu, Geneva, and Washington, D.C., hopes to further the work of the Committee by providing independent information concerning the rights protected under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR),1 and other international and regional human rights instruments which Kenya has ratified.2 The letter provides supplemental information on the following issues of concern regarding the sexual and reproductive rights of Kenyan women and girls: the high rate of preventable maternal mortality and morbidity; the abuse and mistreatment of women that attend maternal health care services; inaccessibility of safe abortion services and post-abortion care; lack of access to comprehensive family planning services and information; and discrimination resulting in gender-based violence and female genital mutilation. I. The Right to Equality and Non-Discrimination It has long been recognized that the obligation to ensure the rights -

Women in Action in Tunisia

ISSUE BRIEF 06.24.20 Women in Action in Tunisia Khedija Arfaoui, Ph.D., Independent Human Rights Researcher Tunisia has long been recognized for its concern is the status of women in state progressive attitude toward women,1 with institutions, including courts, police stations, feminist organizations emerging as early and gendarmeries. Nine years after the as 1936.2 Moroccan author Tahar Ben 2011 uprisings, Tunisian women have not Jelloun suggests that, “[Tunisia] is the most lost any of their rights, but the move for progressive country in the Arab world.”3 equality is far from over and the need to Caroline Perrot asserts that “Tunisia is seen change societal norms remains a core issue. as a forerunner for women's rights in the Discrimination has persisted in Tunisia and it Arab world.”4 Valentine Moghadam shares seems the freedoms granted to women were the same view, stating, “Legal reforms mostly implemented in order to improve made Tunisia the most liberal country in the country’s reputation in the West. This the Arab world.”5 Women have been able brief aims to further an understanding of the to successfully lobby the government to substantive changes, if any, that women in ratify the Commission on the Elimination of Tunisia have experienced. Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW)6 and have demanded action against all forms of discrimination and violence.7 Women RECENT ACHIEVEMENTS AND continued to elevate their status after the SETBACKS IN WOMEN’S EQUALITY 2011 uprising using grassroots mobilization Education efforts, leading to support from politicians. Previously, decisions about women’s The government’s will to decrease gender status were made at the government level inequality has allowed women’s access to and women were not consulted. -

Greta Thunberg: the Voice of Our Planet

Berkeley Leadership Case Series 21-180-017 February 16, 2021 1 Greta Thunberg: The Voice of Our Planet “Over 1,000 students and adults sit alongside Greta on the last day of the school strike. Media and news reporters from several different countries gather around the crowd at Mynttorget Square. Many people believe she has achieved more for the climate than most politicians and the mass media has done in years. But Greta seems to disagree. “Nothing has changed,” she says. “The emissions continue to increase and there is no change in sight.” - Malena Ernman (Greta Thunberg’s mother) i At the age of 17, Greta Thunberg is one of the most powerful voices in the global movement addressing Earth’s climate crisis. Thunberg has successfully stepped up to create a call to action, reached a massive audience, and rallied support across multiple nations. Her activism and sudden rise to the world stage has earned her numerous honors as the youngest Time Person of the Year and two-time Nobel Peace Prize nominee. “The Greta Thunberg Effect”, as journalists have dubbed it, has compelled politicians and government officials to focus on climate change. Despite her accolades, however, Thunberg believes there remains much to do before the planet is truly safe and healthy. “Our house is still on fire,” she warned earlier this year. Going forward, how can Thunberg scale her movement to deliver substantive policy change? The Problem of Climate Change Since the mid-20th century, scientists and researchers have attributed the exponential increase in global temperature (see Exhibit 1) to an increase in human activity. -

Everyday Feminism in the Digital Era: Gender, the Fourth Wave, and Social Media Affordances

EVERYDAY FEMINISM IN THE DIGITAL ERA: GENDER, THE FOURTH WAVE, AND SOCIAL MEDIA AFFORDANCES A Dissertation Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY by Urszula M. Pruchniewska May 2019 Examining Committee Members: Carolyn Kitch, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Media and Communication Adrienne Shaw, Media and Communication Rebecca Alpert, Religion ABSTRACT The last decade has seen a pronounced increase in feminist activism and sentiment in the public sphere, which scholars, activists, and journalists have dubbed the “fourth wave” of feminism. A key feature of the fourth wave is the use of digital technologies and the internet for feminist activism and discussion. This dissertation aims to broadly understand what is “new” about fourth wave feminism and specifically to understand how social media intersect with everyday feminist practices in the digital era. This project is made up of three case studies –Bumble the “feminist” dating app, private Facebook groups for women professionals, and the #MeToo movement on Twitter— and uses an affordance theory lens, examining the possibilities for (and constraints of) use embedded in the materiality of each digital platform. Through in-depth interviews and focus groups with users, alongside a structural discourse analysis of each platform, the findings show how social media are used strategically as tools for feminist purposes during mundane online activities such as dating and connecting with colleagues. Overall, this research highlights the feminist potential of everyday social media use, while considering the limits of digital technologies for everyday feminism. This work also reasserts the continued need for feminist activism in the fourth wave, by showing that the material realities of gender inequality persist, often obscured by an illusion of empowerment. -

Hip Hop Feminism Comes of Age.” I Am Grateful This Is the First 2020 Issue JHHS Is Publishing

Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2020 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 7, Iss. 1 [2020], Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Travis Harris Managing Editor Shanté Paradigm Smalls, St. John’s University Associate Editors: Lakeyta Bonnette-Bailey, Georgia State University Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Willie "Pops" Hudson, Azusa Pacific University Javon Johnson, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Elliot Powell, University of Minnesota Books and Media Editor Marcus J. Smalls, Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) Conference and Academic Hip Hop Editor Ashley N. Payne, Missouri State University Poetry Editor Jeffrey Coleman, St. Mary's College of Maryland Global Editor Sameena Eidoo, Independent Scholar Copy Editor: Sabine Kim, The University of Mainz Reviewer Board: Edmund Adjapong, Seton Hall University Janee Burkhalter, Saint Joseph's University Rosalyn Davis, Indiana University Kokomo Piper Carter, Arts and Culture Organizer and Hip Hop Activist Todd Craig, Medgar Evers College Aisha Durham, University of South Florida Regina Duthely, University of Puget Sound Leah Gaines, San Jose State University Journal of Hip Hop Studies 2 https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol7/iss1/1 2 Halliday and Payne: Twenty-First Century B.I.T.C.H. Frameworks: Hip Hop Feminism Come Elizabeth Gillman, Florida State University Kyra Guant, University at Albany Tasha Iglesias, University of California, Riverside Andre Johnson, University of Memphis David J. Leonard, Washington State University Heidi R. Lewis, Colorado College Kyle Mays, University of California, Los Angeles Anthony Nocella II, Salt Lake Community College Mich Nyawalo, Shawnee State University RaShelle R.