Strategic Nonviolent Power: the Science of Satyagraha Mark A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

Nonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings During Popular Uprisings

Special Report Series Volume No. 2, April 2018 www.nonviolent-conflict.org Nonviolent Resistance and Prevention of Mass Killings During Popular Uprisings Evan Perkoski and Erica Chenoweth Abstract What drives governments to crack down on and kill their own civilians? And how—and to what extent— has nonviolent resistance historically mitigated the likelihood of mass killings? This special report explores the factors associated with mass killings: when governments intentionally kill 1,000 or more civilian noncombatants. We find that these events are surprisingly common, occurring in just under half of all maximalist popular uprisings against states, yet they are strongly associated with certain types of resistance. Nonviolent uprisings that are free of foreign interference and that manage to gain military defections tend to be the safest. These findings shed1 light on how both dissidents and their foreign allies can work together to reduce the likelihood of violent confrontations. Summary What drives governments to crack down on and kill their own civilians? And how—and to what extent—has nonviolent resistance mitigated the likelihood of mass killings? This special report explores the factors associated with mass killings: when governments intentionally kill 1,000 or more civilian noncombatants. We find that these events are surprisingly common, occurring in just under half of maximalist popular uprisings against the states, yet they are strongly associated with certain types of resistance. Specifically, we find that: • Nonviolent resistance is generally less threatening to the physical well-being of regime elites, lowering the odds of mass killings. This is true even though these campaigns may take place in repressive contexts, demand that political leaders share power or step aside, and are historically quite successful at toppling brutal regimes. -

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years Ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 Pages This PDF History Timeline Has Been Extracted

History Timeline from 13.7 Billion Years ago to August 2013. 1 of 588 pages This PDF History Timeline has been extracted from the History World web site's time line. The PDF is a very simplified version of the History World timeline. The PDF is stripped of all the links found on that timeline. If an entry attracts your interest and you want further detail, click on the link at the foot of each of the PDF pages and query the subject or the PDF entry on the web site, or simply do an internet search. When I saw the History World timeline I wanted a copy of it for myself and my family in a form that we could access off-line, on demand, on the device of our choice. This PDF is the result. What attracted me particularly about the History World timeline is that each event, which might be earth shattering in itself with a wealth of detail sufficient to write volumes on, and indeed many such events have had volumes written on them, is presented as a sort of pared down news head-line. Basic unadorned fact. Also, the History World timeline is multi-faceted. Most historic works focus on their own area of interest and ignore seemingly unrelated events, but this timeline offers glimpses of cross-sections of history for any given time, embracing art, politics, war, nations, religions, cultures and science, just to mention a few elements covered. The view is fascinating. Then there is always the question of what should be included and what excluded. -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

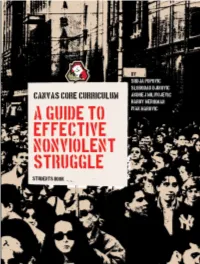

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’S Fight for Civil Rights

DISCUSSION GUIDE The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights PBS.ORG/indePendenTLens/POWERBROKER Table of Contents 1 Using this Guide 2 From the Filmmaker 3 The Film 4 Background Information 5 Biographical Information on Whitney Young 6 The Leaders and Their Organizations 8 From Nonviolence to Black Power 9 How Far Have We Come? 10 Topics and Issues Relevant to The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights 10 Thinking More Deeply 11 Suggestions for Action 12 Resources 13 Credits national center for MEDIA ENGAGEMENT Using this Guide Community Cinema is a rare public forum: a space for people to gather who are connected by a love of stories, and a belief in their power to change the world. This discussion guide is designed as a tool to facilitate dialogue, and deepen understanding of the complex issues in the film The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights. It is also an invitation to not only sit back and enjoy the show — but to step up and take action. This guide is not meant to be a comprehensive primer on a given topic. Rather, it provides important context, and raises thought provoking questions to encourage viewers to think more deeply. We provide suggestions for areas to explore in panel discussions, in the classroom, in communities, and online. We also provide valuable resources, and connections to organizations on the ground that are fighting to make a difference. For information about the program, visit www.communitycinema.org DISCUSSION GUIDE // THE POWERBROKER 1 From the Filmmaker I wanted to make The Powerbroker: Whitney Young’s Fight for Civil Rights because I felt my uncle, Whitney Young, was an important figure in American history, whose ideas were relevant to his generation, but whose pivotal role was largely misunderstood and forgotten. -

The Futility of Violence I. Gandhi's Critique of Violence for Gandhi, Political

CHAPTER ONE The Futility of Violence I. Gandhi’s Critique of Violence For Gandhi, political life was, in a profound and fundamental sense, closely bound to the problem of violence. At the same time, his understanding and critique of violence was multiform and layered; violence’s sources and consequences were at once ontological, moral and ethical, as well as distinctly political. Gandhi held a metaphysical account of the world – one broadly drawn from Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist philosophy – that accepted himsa or violence to be an ever-present and unavoidable fact of human existence. The world, he noted, was “bound in a chain of destruction;” the basic mechanisms for the reproduction of biological and social life necessarily involved continuous injury to living matter. But modern civilization – its economic and political institutions as well as the habits it promoted and legitimated – posed the problem of violence in new and insistent terms. Gandhi famously declared the modern state to represent “violence in a concentrated and organized form;” it was a “soulless machine” that – like industrial capitalism – was premised upon and generated coercive forms of centralization and hierarchy.1 These institutions enforced obedience through the threat of violence, they forced people to labor unequally, they oriented desires towards competitive material pursuits. In his view, civilization was rendering persons increasingly weak, passive, and servile; in impinging upon moral personality, modern life degraded and deformed it. This was the structural violence of modernity, a violence that threatened bodily integrity but also human dignity, individuality, and autonomy. In this respect, Gandhi’s deepest ethical objection to violence was closely tied to a worldview that took violence to inhere in modern modes of politics and modern ways of living. -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

Anniversary of the Thalhimers Lunch Counter Sit-In

TH IN RECOGNITION OF THE 50 ANNIVERSARY OF THE THALHIMERS LUNCH COUNTER SIT-IN Photo courtesy of Richmond Times Dispatch A STUDY GUIDE FOR THE CLASSROOM GRADES 7 – 12 © 2010 CenterStage Foundation Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Standards of Learning 4 Historical Background 6 The Richmond 34 10 Thalhimers Sit-Ins: A Business Owner’s Experience 11 A Word a Day 15 Can Words Convey 19 Bigger Than a Hamburger 21 The Civil Rights Movement (Classroom Clips) 24 Sign of the Times 29 Questioning the Constitution (Classroom Clips) 32 JFKs Civil Rights Address 34 Civil Rights Match Up (vocabulary - grades 7-9) 39 Civil Rights Match Up (vocabulary - grades 10-12) 41 Henry Climbs a Mountain 42 Thoreau on Civil Disobedience 45 I'm Fine Doing Time 61 Hiding Behind the Mask 64 Mural of Emotions 67 Mural of Emotions – Part II: Biographical Sketch 69 A Moment Frozen in Our Minds 71 We Can Change and Overcome 74 In My Own Words 76 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Contributing Authors Dr. Donna Williamson Kim Wasosky Elizabeth Thalhimer Smartt Janet Krogman Jon King The lessons in this guide are designed for use in grades 7 – 12, and while some lessons denote specific grades, many of the lessons are designed to be easily adapted to any grade level. All websites have been checked for accuracy and appropriateness for the classroom, however it is strongly recommended that teachers check all websites before posting or otherwise referencing in the classroom. Images were provided through the generous assistance and support of the Valentine Richmond History Center and the Virginia Historical Society. -

MARTIN LUTHER KING and the PHILOSOPHY of NONVIOLENCE Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia

Bill of Rights Constitutional Rights in Action Foundation SUMMER 2017 Volume 32 No4 MARTIN LUTHER KING AND THE PHILOSOPHY OF NONVIOLENCE Wikimedia Commons Wikimedia Martin Luther King, Jr. addressing the crowd of about 250,000 people at the March on Washington in August 1963. Martin Luther King, Jr. is remembered for his achievements The man, who turned out to be an American Nazi Party in civil rights and for the methods he used to get there — member, continued to flail. namely, nonviolence. More than just a catchphrase, more than just the “absence of violence,” and more than just a tactic, The integrated audience at first thought the whole nonviolence was a philosophy that King honed over the thing was staged, a mock demonstration of King’s non- course of his adult life. It has had a profound, lasting influ- violent philosophy in action. But as King reeled, and real ence on social justice movements at home and abroad. blood spurted from his face, they began to realize it was In September 1962, King convened a meeting of the no act. Finally, several SCLC members rushed the stage Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the to stop the attack. main organizational force behind his civil rights activism, But they stopped short when King shouted, “Don’t in Birmingham, Alabama. King was giving a talk on the touch him! Don’t touch him! We have to pray for him.” need for nonviolent action in the face of violent white The SCLC men pulled the Nazi off King, who was beaten racism when a white man jumped on stage and, without so badly he couldn’t continue the speech. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 “Beyond Anxiety,” editorial, New York Times, June 13, 1982, E22. 2 For the purposes of simplicity, this book refers to the assemblage of actors engaged in various types of activism against nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and other related threats as the “anti-nuclear movement.” Although I detail individual movements within the larger whole, the existence of substantial cross-pollination among movement organizations and coalitions indicates that a more appropriate term is the singular. On the idea of a “movement of movements,” see Van Gosse, “A Movement of Movements: The Definition and Periodization of the New Left,” in A Companion to Post-1945 America, ed. Jean-Christophe Agnew and Roy Rosenzweig (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2002), 277–302. 3 On this diversity, see Jo Freeman and Victoria Johnson, eds, Waves of Protest: Social Movements Since the Sixties (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999). See also Simon Hall, American Patriotism, American Protest: Social Movements Since the Sixties (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011). 4 See Fred Halliday, The Making of the Second Cold War (London: Verso, 1983). 5 On beginnings, see Lawrence S. Wittner, Toward Nuclear Abolition: A His- tory of the World Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1971 to the Present (Stan- ford: Stanford University Press, 2003), Chapter 1. On the dwindling of the movement, see “Movement Gap,” editorial, Nation, 4 November 1991, 539–40. 6 The phrase “the challenge of peace” recalls the controversial pastoral letter issued in 1983 by the US National Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Ad Hoc Committee on War and Peace. Entitled “The Challenge of Peace: God’s Prom- ise and Our Response,” the letter attempted to define the Catholic Church’s opposition to the nuclear arms race. -

From Pariah to Partner: the US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015

INDIA BHUTAN CHINA BAN GLADESH VIETNAM Naypidaw Chiang Mai LAOS Rangoon THAILAND Bangkok CAMBODIA From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 From Pariah to Partner The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma Making Peace Possible 2009 to 2015 2301 Constitution Avenue NW Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone.