Jesus and the Nonviolent Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Roman Province of Judea: a Historical Overview

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 36 Issue 3 Article 23 7-1-1996 The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview John F. Hall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Part of the Mormon Studies Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Hall, John F. (1996) "The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 36 : Iss. 3 , Article 23. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol36/iss3/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hall: The Roman Province of Judea: A Historical Overview p d tffieffiAinelixnealxAIX romansixulalealliki glnfin ns i u1uaihiihlanilni judeatairstfsuuctfa Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 1996 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 36, Iss. 3 [1996], Art. 23 the roman province judeaofiudeaofofjudea A historical overview john E hall the comingcoining of rome to judea romes acquisition ofofjudeajudea and subsequent involvement in the affairs of that long troubled area came about in largely indirect fashion for centuries judea had been under the control of the hel- lenilenisticstic greek monarchy centered in syria and known as the seleu- cid empire one of the successor states to the far greater empire of alexander the great who conquered the vast reaches of the persian empire toward the end of the fourth century -

Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements

BETWEEN MAO AND GANDHI: STRATEGIES OF VIOLENCE AND NONVIOLENCE IN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENTS A thesis Presented to the Faculty of The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy by CHES THURBER In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Dissertation Committee: Richard Shultz, Chair H. Zeynep Bulutgil Erica Chenoweth CHES THURBER 104 E. Main St. #2, Gloucester, MA 02155 [email protected] | (617) 710-2617 DOB: September 21, 1982 in New York, NY, USA EDUCATION Tufts University, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy PH.D. | International Relations (2015) Dissertation: “Between Mao and Gandhi: Strategies of Violence and Nonviolence in Revolutionary Movements” Committee: Richard Shultz, Zeynep Bulutgil, Erica Chenoweth M.A.L.D. | International Relations (2010) Middlebury College B.A. | International Studies (summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa, 2004) ACADEMIC University of Chicago APPOINTMENTS Postdoctoral Fellow, Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (Beginning Aug. 1, 2015) Program on Political Violence Harvard University Research Fellow, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs (2014-2015) International Security Program PUBLICATIONS “Militias as Sociopolitical Movements: Lessons from Iraq’s Armed Shia Groups" in Small Wars and Insurgencies 25, nos. 5-6 (October 2014): 900-923. Review of The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: Revolution in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Mahendra Lawoti and Anuk K. Pahari, in Himalaya 34, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 148-150. “A Step Short of the Bomb: Explaining the Strategy of Nuclear Hedging” in Journal of Public and International Affairs (2011). “From Coexistence to Cleansing: The Rise of Sectarian Violence in Baghdad, 2003-2006” in al-Nakhlah: Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization (March 2011). -

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

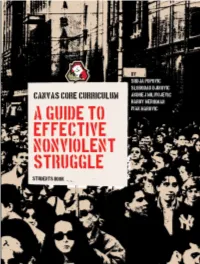

Canvas Core Curriculum: a Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle

CANVAS CORE CURRICULUM: A GUIDE TO EFFECTIVE NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE STUDENTS BOOK by CANVAS printed and published in Serbia 2007 CANVAS Curriculum Introduction Before you is a wealth of knowledge about the planning, conduct, and Srdja Popovic, Slobodan Djinovic, Andrej Milivojevic, Hardy Merriman evaluation of strategic nonviolent conflict. This curriculum guide will be a and Ivan Marovic valuable companion to new and experienced activists, as well as to others who wish to learn about this subject. CANVAS Core Curriculum: A Guide to Effective Nonviolent Struggle Copyright 2007 by CANVAS. All rights reserved. The authors combine classic insights about nonviolent conflict with new ideas based on recent experience. The result is a synthesis that pushes the Published in Serbia, 2007. limits of what we thought nonviolent strategies were capable of achieving. The material covered includes time-tested analyses of power, different ISBN 978-86-7596-087-4 methods of nonviolent action, and ways to create a strategic plan for developing and mobilizing a movement. In addition, the authors include new material about how to: Publisher: Centre for Applied Nonviolent Action and Strategies (CANVAS) • chart a movement’s history and progress (Chapter 8) Masarikova 5/ XIII, Belgrade, Serbia, www.canvasopedia.org • use marketing, branding, and effective communication techniques in a movement (Chapters 9 and 10) Graphic design and illustrations: Ana Djordjevic • address the effects of fear on a movement’s members (Chapter 13) • develop security measures within a movement (Chapter 14) Photo on cover: Igor Jeremic • manage a movement’s material resources, human resources, and time (Advanced Chapters 2-4) Throughout these topics, the authors emphasize pragmatic learning and draw on their own experience applying these ideas in their own struggles. -

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople1

STEFANOS ATHANASIOU The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople1 A Religious Minority and a Global Player Introduction In the extended family of the Orthodox Church of the Byzantine rite, it is well known that the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople takes honorary prece- dence over all other Orthodox autocephalous and autonomous churches.2 The story of its origins is well known. From a small church on the bay of the Bos- porus in the fishing village of Byzantium, to the centre of Eastern Christianity then through the transfer of the Roman imperial capital from Rome to Constantinople in the fourth century, and later its struggle for survival in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey. Nevertheless, a discussion of the development of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople is required to address the newly- kindled discussion between the 14 official Orthodox autocephalous churches on the role of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in today’s Orthodox world. A recalling of apposite historical events is relevant to this discussion. As Karl Löwith remarks, “[H]istorical consciousness can only begin with itself, although its intention is to visualise the thinking of other times and other people. History must continually be recalled, reconsidered and re-explored by each current living generation” (Löwith 2004: 12). This article should also be understood with this in mind. It is intended to awaken old memories for reconsideration and reinterpretation. Since the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Ecumenical Patriarchate has taken up the role of custodian of the Byzantine tradition and culture and has lived out this tradition in its liturgical life in the region of old Byzantium (Eastern Roman Empire) and then of the Ottoman Empire and beyond. -

Jeffrey Eli Pearson

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4dx9g1rj Author Pearson, Jeffrey Eli Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture By Jeffrey Eli Pearson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Erich Gruen, Chair Chris Hallett Andrew Stewart Benjamin Porter Spring 2011 Abstract Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture by Jeffrey Eli Pearson Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Erich Gruen, Chair The Nabataeans, best known today for the spectacular remains of their capital at Petra in southern Jordan, continue to defy easy characterization. Since they lack a surviving narrative history of their own, in approaching the Nabataeans one necessarily relies heavily upon the commentaries of outside observers, such as the Greeks, Romans, and Jews, as well as upon comparisons of Nabataean material culture with Classical and Near Eastern models. These approaches have elucidated much about this -

The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: a Strategic and Historical Analysis

ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES The Tibetan Nonviolent Struggle: A Strategic and Historical Analysis Tenzin Dorjee ICNC MONOGRAPH SERIES Cover photos: (l) John Ackerly, 1987, (r) Invisible Tibet Blog SERIES EDITOR: Maciej Bartkowski John Ackerly’s photo of the first major demonstration in Lhasa in 1987 CONTACT: [email protected] became an emblem for the Tibet movement. The monk Jampa Tenzin, who is being lifted by fellow protesters, had just rushed into a burning VOLUME EDITORS: Hardy Merriman, Amber French, police station to rescue Tibetan detainees. With his arms charred by the Cassandra Balfour flames, he falls in and out of consciousness even as he leads the crowd CONTACT: [email protected] in chanting pro-independence slogans. The photographer John Ackerly Other volumes in this series: became a Tibet advocate and eventually President of the International Campaign for Tibet (1999 to 2009). To read more about John Ackerly’s The Power of Staying Put: Nonviolent Resistance experience in Tibet, see his book co-authored by Blake Kerr, Sky Burial: against Armed Groups in Colombia, Juan Masullo An Eyewitness Account of China’s Brutal Crackdown in Tibet. (2015) Invisible Tibet Blog’s photo was taken during the 2008 Tibetan uprising, The Maldives Democracy Experience (2008-13): when Tibetans across the three historical provinces of Tibet rose up From Authoritarianism to Democracy and Back, to protest Chinese rule. The protests began on March 10, 2008, a few Velezinee Aishath (2015) months ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games, and quickly became the largest, most sustained nonviolent movement Tibet has witnessed. Published by the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict The designations used and material presented in this publication do P.O. -

JARED JAMES NICHOLS Ne Peut Remettre En Cause L’Intégrité Musicale D’Une Personne

EDITO EDITO NOVEMBRE/DÉCEMBRE 2017 Le plaisir partagé par les fans de musique (extrême SOMMAIRE ou pas, là n’est pas la question) ne doit pas opposer. L’aventure « musicale » de l’un n’est peut-être pas la 04. Interview BELPHEGOR même pour l’autre. L’un n’y connaît peut-être rien, l’autre est peut-être une bête de culture - l’un pré- 06. Interview SAMAEL fère télécharger, l’autre se ruiner… Mais jamais on 08. Interview JARED JAMES NICHOLS ne peut remettre en cause l’intégrité musicale d’une personne. 10. Interview HEIR 12. Interview THE WITCH La « diversité » (ce gros mot !!!!!) musicale est notre credo chez Heretik. Mais surtout, surtout, surtout, ce 13. Interview STENGAH qui nous motive avant tout, c’est le fait de partager 14. Interview VIRGIL nos groupes « coups de cœur » et nos découvertes… ! Vous êtes nombreux à nous remercier de vous avoir 15. Interview MINDSLOW fait découvrir tel ou tel groupe. Nous vous rendons la 16. Interview FRAKASM pareille. Merci à vous de faire de ce magazine LE pas- seur de la culture Rock/Metal des Hauts-de-France 18. En Chair et en Encre ! Mais surtout, surtout, surtout (bis), n’oubliez pas 20. Tout ce que vous direz sera retenu de vous rendre aux concerts, car c’est là que se joue contre vous ! l’avenir de nos futures valeurs sûres ! 22. Live Report RAISMES FEST Aujourd’hui encore, nous ne sommes que trop 24. Live Report Du Metal À La Campagne peu à nous rendre aux concerts locaux. Certains se plaignent qu’il n’y ait plus d’endroit où se produire. -

Cyprus and British Colonialism: a Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict Ormationf

Peace and Conflict Studies Volume 25 Number 1 Decolonizing Through a Peace and Article 6 Conflict Studies Lens 5-2018 Cyprus and British Colonialism: A Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict ormationF Kristian Fics University of Manitoba, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs Part of the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fics, Kristian (2018) "Cyprus and British Colonialism: A Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict Formation," Peace and Conflict Studies: Vol. 25 : No. 1 , Article 6. DOI: 10.46743/1082-7307/2018.1441 Available at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs/vol25/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Peace & Conflict Studies at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peace and Conflict Studies by an authorized editor of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cyprus and British Colonialism: A Bowen Family Systems Analysis of Conflict Formation Abstract This article uses family systems theory and Bowen family systems psychotherapy concepts to understand the nature of conflict formation during British colonialism in Cyprus. In examining ingredients of the British colonial model through family systems theory, an argument is made regarding the multigenerational transmission of colonial patterns that aid in the perpetuation of the Cyprus conflict ot the present day. The ingredients of the British colonial model discussed include the homeostatic maintenance of the Ottoman colonial structure, a divide and rule policy through triangulation, the use of nationalism and triangulation in the Cypriot education system, political exploitation, and apartheid laws. Explaining how it centers on relationships and circular causality, nonsummativity and homeostasis reveals the useful nature of family systems theories in understanding conflict formation. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

Late Ottoman Empire

01_Hanioglu_Prelims_p00i-pxviii.indd i 8/23/2007 7:33:25 PM 01_Hanioglu_Prelims_p00i-pxviii.indd ii 8/23/2007 7:33:25 PM A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE Late Ottoman Empire M. Şükrü Hanioğlu 01_Hanioglu_Prelims_p00i-pxviii.indd iii 8/23/2007 7:33:26 PM Copyright © 2008 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-691-13452-9 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Minion Typeface Printed on acid-free paper. ∞ press.princeton.edu Printed in the United States of America 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 01_Hanioglu_Prelims_p00i-pxviii.indd iv 8/23/2007 7:33:26 PM 01_Hanioglu_Prelims_p00i-pxviii.indd v 8/23/2007 7:33:26 PM Mazi ve müstakbel ahvâline vakıf ve belki ezel ve ebed esrarını ârif olmağa insanda bir meyl-i tabiî olduğundan ale-l-umum nev>-i beșerin bu fenne [tarih] ihtiyac-ı ma>nevîsi derkârdır. Since man has a natural aptitude for comprehending past and future affairs, and perhaps also for unlocking the secrets of eternities past and future, humanity’s spiritual need for this science [history] is evident. —Ahmed Cevdet, Tarih-i Cevdet, 1 (Istanbul: Matbaa-i Osmaniye, 1309 [1891]), pp. 16–17 01_Hanioglu_Prelims_p00i-pxviii.indd vi 8/23/2007 7:33:26 PM Contents List of Figures ix Acknowledgments xi Note on Transliteration, Place Names, and Dates xiii Introduction 1 1. The Ottoman Empire at the Turn of the Nineteenth Century 6 2. -

Authoritarian Politics and the Outcome of Nonviolent Uprisings

Authoritarian Politics and the Outcome of Nonviolent Uprisings Jonathan Sutton Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy National Centre for Peace and Conflict Studies/Te Ao o Rongomaraeroa University of Otago/Te Whare Wānanga o Otāgo July 2018 Abstract This thesis examines how the internal dynamics of authoritarian regimes influence the outcome of mass nonviolent uprisings. Although research on civil resistance has identified several factors explaining why campaigns succeed or fail in overthrowing autocratic rulers, to date these accounts have largely neglected the characteristics of the regimes themselves, thus limiting our ability to understand why some break down while others remain cohesive in the face of nonviolent protests. This thesis sets out to address this gap by exploring how power struggles between autocrats and their elite allies influence regime cohesion in the face of civil resistance. I argue that the degeneration of power-sharing at the elite level into personal autocracy, where the autocrat has consolidated individual control over the regime, increases the likelihood that the regime will break down in response to civil resistance, as dissatisfied members of the ruling elite become willing to support an alternative to the status quo. In contrast, under conditions of power-sharing, elites are better able to guarantee their interests, thus giving them a greater stake in regime survival and increasing regime cohesion in response to civil resistance. Due to the methodological challenges involved in studying authoritarian regimes, this thesis uses a mixed methods approach, drawing on both quantitative and qualitative data and methods to maximise the breadth of evidence that can be used, balance the weaknesses of using either approach in isolation, and gain a more complete understanding of the connection between authoritarian politics and nonviolent uprisings.